The Health Strategist

institute for continuous health transformation

in person and digital health

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Chief Research and Strategy Officer (CRSO)

May 6, 2023

ONE PAGE SUMMARY

The article highlights the increasing involvement of private equity (PE) firms in the US health care industry and raises concerns about its implications.

- The study discussed in the article focuses on the surge in PE acquisition of oncology clinics over the past two decades.

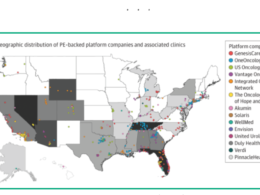

- It reveals that in several states, one out of every four oncology clinics is now owned by a PE company.

- This trend is driven by the potential profitability associated with chemotherapy administration and the high prices of oncology drugs.

- Additionally, community-based oncologists may be more willing to engage in PE arrangements due to the strain of dealing with administrative burdens, as PE-backed entities offer enhanced back-office resources.

The article emphasizes several critical issues resulting from the increased prevalence of PE ownership in health care.

- It questions whether PE engagement has reached a tipping point, given that PE firms have acquired more than 1300 women’s health clinical practices, and significant numbers of dermatologists, oncologists, anesthesiologists, hospitals, and hospice facilities.

- The fundamental business strategies of PE firms, which involve purchasing practices, maximizing revenues, cutting costs, consolidating entities, and selling within a few years for significant returns, raise concerns about short-term profitability overshadowing long-term investment in the success of medical practices.

The authors cite studies indicating that PE ownership is associated with increased charges per claim and higher cost trajectories.

- However, the impact on quality measures is still being studied, with some suggesting a deterioration in quality and others suggesting stable or improved quality.

To address the implications of PE ownership in health care, the article calls for urgent action in three domains:

- increasing understanding,

- enhancing oversight, and

- reconsidering structural incentives.

Physicians and physicians in training need to understand the hazards of PE acquisition and potential loss of decision-making control.

- Rigorous studies are necessary to assess the association of PE ownership with patient access, quality, and outcomes.

- Enhanced scrutiny is required, as many PE-backed acquisitions of small or mid-size practice groups fall below the threshold for Federal Trade Commission (FTC) review.

The authors suggests that the FTC should lower the threshold for examining PE acquisition of physician practices and focus antitrust efforts on major consolidations in key markets.

- Congress should also reconsider current incentives that favor PE involvement in health care.

- Payment reform in cancer care, such as moving away from the “buy and bill” model and revising federal tax regulations to remove the carried interest tax loophole, are recommended to mitigate the impact of PE ownership.

The article concludes that if the selling of critical components of the health care infrastructure works contrary to the goals of optimizing health and well-being, both the buyers (PE firms) and the sellers (physicians and health care organizations) should be cautious.

- It suggests the need for more public transparency and monitoring by Congress and the FTC to better regulate these transactions for the protection of all stakeholders.

DEEP DIVE

Private Equity in US Health Care — Now Cradle to Grave?

JAMA Intern Med.

Francis J. Crosson, MD1; Isabel R. Ostrer, MD2; Cary P. Gross, MD3

Published online May 1, 2023.

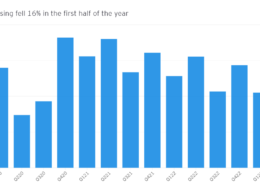

In this issue of JAMA Internal Medicine, Tyan and colleagues1 report that private equity (PE) involvement and acquisition of oncology clinics in the US has surged over the past 20 years.

In several states, 1 of every 4 oncology clinics is owned by a PE company. It is no surprise, given the profit potential directly related to the volume of chemotherapy administered and payment of oncologists as a percentage of the sales price of these increasingly high-priced drugs.

At the same time, community-based oncologists may be increasingly willing to engage in PE arrangements due to strain from dealing with prior authorizations and other nonclinical aspects of care, given that the PE–backed entities may have more so-called back-office resources to devote to enhancing efficiency of clinician workflow.2

The study raises several crucial issues.

First, has PE engagement in US health care reached a tipping point?

Consider a hypothetical life trajectory, beginning with birth: as of 2020, more than 1300 women’s health clinical practices had been purchased by PE firms.3

We then transition to adulthood: a woman might be diagnosed with melanoma (nearly 10% of dermatologists and oncologists now work in a practice owned by PE)4 and undergo surgical lymph node dissection (more than 1800 anesthesiologists work in practices owned by PE).5

Later, she may need care in a hospital (PE owns 4% of US hospitals)4 or a hospice (as of 2019, approximately 7.7% of Medicare hospice enrollees were in PE–owned facilities).6

The increased prevalence of PE ownership in health care is particularly concerning due to the fundamental business strategies of these firms:

purchase practices, aggressively enhance revenues and cut costs, consolidate into larger entities

This profit model heightens the focus on short-term profitability at the expense of longer-term investment in the success of the practice.

A 2022 study of 578 dermatology, gastroenterology, and ophthalmology physician practices acquired by PE companies found that there was a 20% increase in charges per claim.7

Private equity acquisition of anesthesia practices was similarly associated with a 26% greater increase in cost trajectory between 2012 and 2017, compared with control practices.8

The body of evidence regarding PE in terms of quality is still evolving, with some studies suggesting a deterioration in quality measures, while other suggest that PE acquisition may be associated with stable or improved quality.9

This shift in the health care landscape calls for urgent action across 3 domains:

increasing our understanding of the implications of PE ownership, enhancing oversight, and reconsidering structural incentives that motivate PE involvement in health care.

First, physicians and physicians in training should understand the potential hazards of PE acquisition to their independence: clinicians can lose decision-making control when their practices are increasingly bundled and sold to larger and larger entities.

The American Medical Association House of Delegates recently voted to sponsor an analysis of this issue.10 At the same time, rigorous studies are needed to better define the association of PE ownership with patient access, quality, and the outcomes of care.

Second, enhanced scrutiny is required, as many PE-backed acquisitions of small or mid-size practice groups are deemed too small for the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to review the acquisitions with regard to anticompetitive practices.

Any FTC actions against PE deals have been minimal to date. In fact, the FTC generally will not review acquisitions if they fall below a specific threshold, which is modified from time to time, and is currently set at $101 million. Acquisitions below this threshold are not thought to be large enough to thwart competition or compromise patient access. Yet the piecemeal approach of sequentially acquiring smaller practices is a factor in the creation of larger and larger entities, as the study by Tyan et al1 shows. To address this concern, the FTC should lower the existing $101 million threshold for examining PE acquisition of physician practices and focus antitrust efforts on major consolidations in key markets.

In addition, Congress should reconsider current incentives that favor PE involvement in health care.

Regarding cancer care, this can be accomplished through payment reform.

One approach, recently recommended by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission,5 is to move away from the so-called buy and bill for Part B drugs, which reimburses oncologists at 106% of the average sales price for drugs, providing oncologists with incentives to choose more expensive medications.

Similarly, federal tax regulations provide incentives for PE ownership of medical practices through lower tax rates:

Congress could remove the carried interest tax loophole which allows PE firms to pay preferential capital gains tax on a substantial proportion of their income, rather than a higher corporate tax on annual earnings.

The US health care system aims to optimize the health and well-being of individuals and communities from cradle to grave.

And if selling of critical components of our health care infrastructure is working contrary to these goals, let the buyers (PE firms) and the sellers (physicians and health care organizations) beware.

More public transparency about what is going on through media coverage would be helpful.

And Congress and the FTC should proceed to monitor and better regulate these transactions for the protection of all.

Published Online: May 1, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0324

References

See the original publication