This is republication of the paper below, with the title above, focusing on the topic in question.

NEJM Catalyst

Disruptive Collaboration: A Thesis for Pro-Competitive Collaboration in Health Care

Carter Dredge, MHA, Dan Liljenquist, JD, and Stefan Scholtes, PhD

March 29, 2022

Executive Summary by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Health Transformation Institute (HTI)

Strategy Advisory Consulting

Cost Reduction Unit

July 13, 2022

Summary

- There are strong arguments for more competition in health care to drive significant improvements in the U.S. system. These arguments are sound, as a general rule.

- However, there are some problems in health care that are so large or complex that to achieve the desired competition, more novel forms of collaboration are also required.

- One form of collaboration — called disruptive collaboration — involves a large number of incumbent firms collaborating to collectively disrupt an entire subindustry.

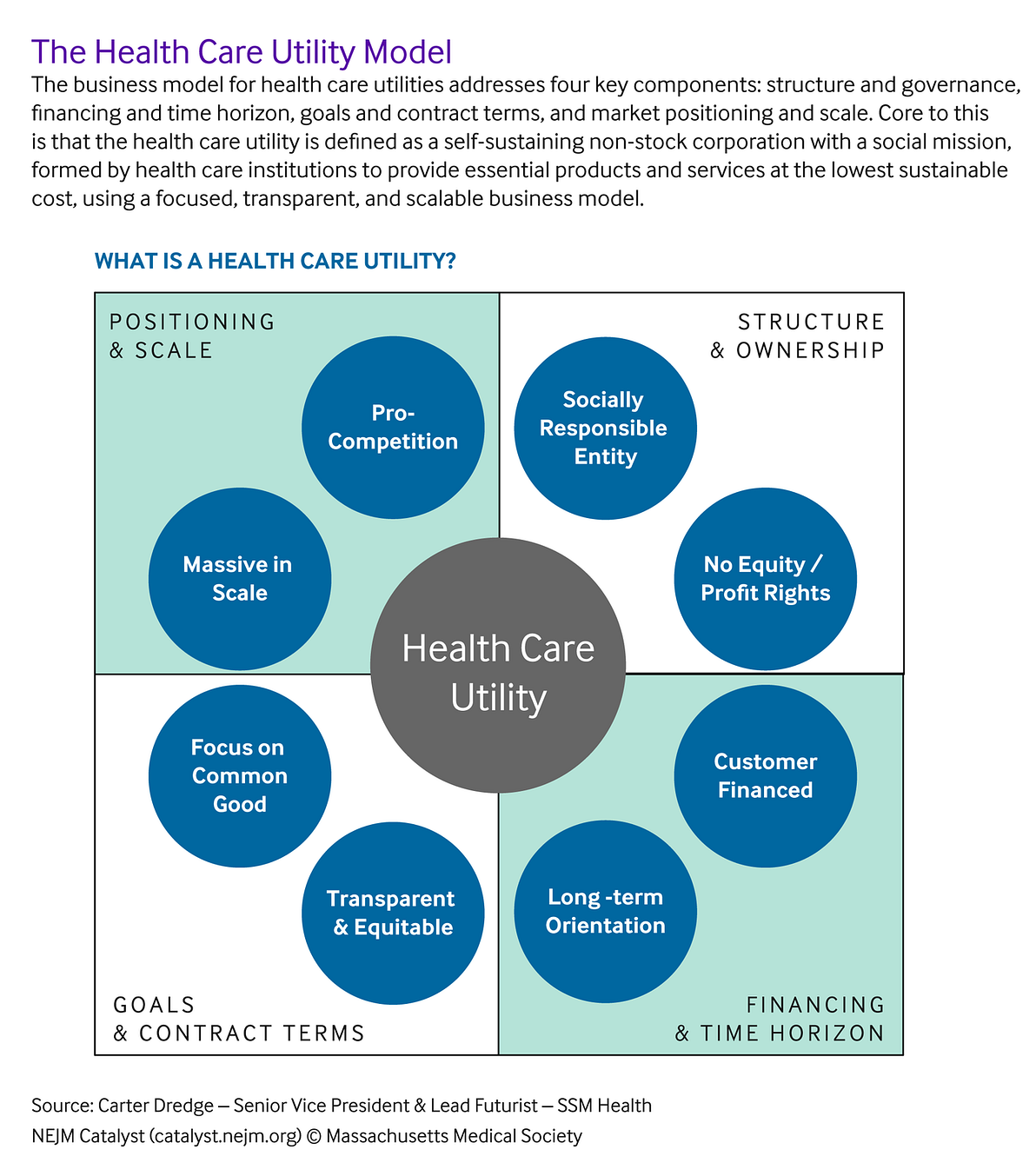

- Such collaboration is scalably facilitated through a new vehicle called the Health Care Utility Model — a novel business model in which incumbent institutions form a self-sustaining, mission-driven corporation to provide essential products and services for customers and society at the lowest sustainable cost.

- Once formed, these health care utilities act as industry-competition boosters in competitively stagnant markets such as those dominated by hard-to-compete-against oligopolies.

Case Study: Civica Rx

- An innovative example of disruptive collaboration occurred in 2018 when health systems across the country formed a new generic drug manufacturer, Civica Rx, to address a generic drug market failure that was causing drug shortages and egregious price hikes.

- In this instance, hospitals didn’t join forces to ward off competition, but instead to bring competition to the generics market — which they did, delivering a stable supply of essential medicines to millions of patients at a 30% lower price point.

- In March 2022, Civica Rx and its sister company, CivicaScript — a retail pharmaceutical manufacturer comprising insurance company members — significantly expanded their disruptive collaboration efforts by announcing they would be offering three low-cost insulin generics to millions of Americans for no more than $30 per vial, representing hundreds of dollars of potential savings each month for people dependent on insulin to live.

- A key element of Civica Rx’s Health Care Utility Model is its customer-financing structure, which eliminates the incentive for higher prices and profits and flips the business strategy from “what is the highest cost that the market will bear” to “what is the lowest sustainable cost that we can deliver to the market.”

Case Study: Graphite Health

- Another tangible example of a disruptive collaboration effort is the 2021 formation of Graphite Health — a nonprofit company modeled after Civica Rx’s member-led, collective approach — that comprises multiple large health systems (SSM Health, Intermountain Healthcare, Presbyterian Healthcare Services, and Kaiser Permanente) …

- … working to accelerate digital transformation through the creation of a democratized digital health-care interoperability platform and marketplace.

- Think of something similar to the Apple App Store, but for health systems as the primary customer instead of individuals.

Structure of the publication:

- Introduction

- Oligopolies in Health Care

- Differing Growth Trajectories: Netflix and Navitus

- The Health Care Utility Model: Rapidly Increasing Speed-to-Scale and Mitigating Risk

- Looking Ahead

Looking Ahead

- A big reason why health care is still stuck in a 20th-century model is because it is heavily populated by oligopolies — of all sorts and specializations — and these oligopolies are very hard to disrupt.

- Health care needs more competition. It also needs more collaboration.

- To compete against these oligopolies, disruptive collaboration is a critical mindset, and the Health Care Utility Model is a key vehicle.

- When they are successfully combined and successively replicated across industry sectors, these health care utility entities have the potential to open a new way of pursuing health care innovation …

- … — something akin to an “open source” health care movement: a nascent movement that could transcend heightened political and competitive divisions to accomplish revolutionary and meaningful change.

- A movement more focused on people and care than profits and share. It is about a call to serve and to heal what’s broken — both clinically and administratively.

The Covid-19 pandemic has taught us many things in health care.

- From a positive perspective, it has shown us how much we can accomplish in a short time period when we all work together for a common objective of helping and healing one another.

- From a negative perspective, it has also taught us how staggeringly unequal access has become to multiple essential health care services.

The type of innovation the authors describe hearkens back

- to the days of the birth of many hospitals in the United States that were founded by communities and religious congregations who came together to accomplish something grander than any one individual could do alone,

- and to a time when the developers of early medicines dearly wanted their discoveries to remain inexpensive to the average consumer because the drugs provided such merciful relief from human suffering.

Large-scale disruption in health care is bound to happen eventually.

What we need to decide is how long do we want it to take and whether the current incumbents will be the disruption facilitators or the barriers.

Time will tell. But we are determined to level the playing field.

A movement more focused on people and care than profits and share. It is about a call to serve and to heal what’s broken — both clinically and administratively.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

Disruptive Collaboration: A Thesis for Pro-Competitive Collaboration in Health Care

NEJM Catalyst

Carter Dredge, MHA, Dan Liljenquist, JD, and Stefan Scholtes, PhD

March 29, 2022

Health care seems to be stuck in a 20th-century service model, and a growing body of research is calling for more competition to fix it.

However, there is still considerable debate as to exactly how and where to implement more competition in health care — and that is literally a trillion-dollar question.

Porter and Lee have compellingly championed a framework for competing on value, Christensen has persuasively prescribed more innovative disruption, and Dafny has credibly cautioned of the expensive consequences of traditional mergers.

We agree that health care needs more competition.

However, we assert that health care also needs more collaboration — not with the traditional goal of protecting the market position of the collaborators, but rather in an innovative form of disruptive collaboration.

Disruptive collaboration takes place when a large number of incumbent firms work collectively to disrupt an entire subindustry; in this regard, disruptive collaboration is about playing offense, not defense.

Case Study: Civica Rx

An innovative example of disruptive collaboration occurred in 2018 when health systems across the country formed a new generic drug manufacturer, Civica Rx, to address a generic drug market failure that was causing drug shortages and egregious price hikes.

In this instance, hospitals didn’t join forces to ward off competition, but instead to bring competition to the generics market — which they did, delivering a stable supply of essential medicines to millions of patients at a 30% lower price point.

In March 2022, Civica Rx and its sister company, CivicaScript — a retail pharmaceutical manufacturer comprising insurance company members — significantly expanded their disruptive collaboration efforts by announcing they would be offering three low-cost insulin generics to millions of Americans for no more than $30 per vial, representing hundreds of dollars of potential savings each month for people dependent on insulin to live.

A key element of Civica Rx’s Health Care Utility Model is its customer-financing structure, which eliminates the incentive for higher prices and profits and flips the business strategy from “what is the highest cost that the market will bear” to “what is the lowest sustainable cost that we can deliver to the market.”

… they would be offering three low-cost insulin generics to millions of Americans for no more than $30 per vial, representing hundreds of dollars of potential savings each month for people dependent on insulin to live.

Case Study: Graphite Health

Another tangible example of a disruptive collaboration effort is the 2021 formation of Graphite Health — a nonprofit company modeled after Civica Rx’s member-led, collective approach — that comprises multiple large health systems (SSM Health, Intermountain Healthcare, Presbyterian Healthcare Services, and Kaiser Permanente) working to accelerate digital transformation through the creation of a democratized digital health-care interoperability platform and marketplace.

Think of something similar to the Apple App Store, but for health systems as the primary customer instead of individuals.

One health system alone would never have the resources or scale to develop and implement such a massive undertaking.

However, a large group of systems working together under the Health Care Utility Model could sufficiently aggregate the demand and clinical expertise necessary to create a de facto data standard that could be used broadly by all to access essential digital health applications (i.e., apps) more efficiently at a low cost.

Disruptive collaboration takes place when a large number of incumbent firms work collectively to disrupt an entire subindustry; in this regard, disruptive collaboration is about playing offense, not defense.

A powerful tenet of disruptive collaboration is that it involves leveraging the current scale and expertise of numerous incumbent institutions to simultaneously address a market failure/inefficiency that, without such collective scale, would otherwise have been beyond the reach of any single traditional new entrant.

This has material strategic implications for addressing one of the most notorious barriers to true competition: oligopolies.

Oligopolies in Health Care

Oligopolies — markets in which a small number of companies play a dominant role — are rampant in health care. The four largest publicly traded health insurance companies cover approximately 50% of the insurable market, the top three electronic health record (EHR) companies garner 72% of the hospital medical records market, the top three pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) have a combined market share of nearly 80%, and the two largest dialysis organizations (LDOs) control an astonishing 80% of the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) dialysis market,,just to name a few. Such market conditions — in addition to third-party institutional reimbursement for services, network adequacy requirements for insurance coverage, and access loss threats if there are service interruptions — make transitioning to disruptively lower-cost services extremely challenging. Let’s unpack this further.

The suppliers of the above-mentioned services (i.e., insurers, EHRs, PBMs, LDOs) have massive scale in their respective services over the purchasers (i.e., employers, health systems, etc.). At the same time, the purchasers of these same services have massive geographic needs/demands that are much larger than most traditional organic new entrants can meet. This results in an odd disruption-resistant paradox: No single purchaser is large enough to fully challenge the oligopoly, and, at the same time, the largest purchasers are too big to be adequately served by a standard start-up. As a consequence, many potential new entrants, the would-be suppliers, find it too risky to enter these spaces, or those that do can expect a very long time horizon for industrywide impact, one wrought with difficulties.

Access loss threats are also significant, and they operate in health care differently than in other industries. For example, let’s consider dialysis treatment. Dialysis is a medical treatment that filters toxins out of the patient’s blood when their kidneys no longer function properly. When an individual’s kidneys fail, the patient has three options: begin dialysis, get a kidney transplant, or choose to die. Dialysis is the default choice for most patients and this treatment needs to be immediately accessible to prevent life-threatening further deterioration of the kidneys. Given that insurance companies need to have adequate network services coverage for their members to sell their insurance products, if an insurance company made an institutional decision that caused a complete falling out with one of the two large dialysis organizations, Fresenius or DaVita, patients could be seriously harmed, and the result would be catastrophic.

This results in an odd disruption-resistant paradox: No single purchaser is large enough to fully challenge the oligopoly, and, at the same time, the largest purchasers are too big to be adequately served by a standard start-up.

This explains the significant institutional risk aversion when potentially even considering exploring disruptive dialysis treatment alternatives. This market dynamic allows the upstream services oligopolists to hold the downstream purchasers hostage in a way not comparable to other industries. To empirically illustrate this intense oligopolist power at work, a recent study showed that government programs (primarily Medicare and Medicaid) paid $248 on average per dialysis session, whereas private insurers paid $1,041 — more than four times the amount for the same treatments.

For a patient receiving standard in-center hemodialysis three times a week, this would equate to private insurers paying an additional cost of approximately $124,000 annually for each patient — roughly $12.4 million for just 100 patients. While there may be some warranted private-market premium above a standard Medicare rate, a four-times multiple seems excessive by any standard.

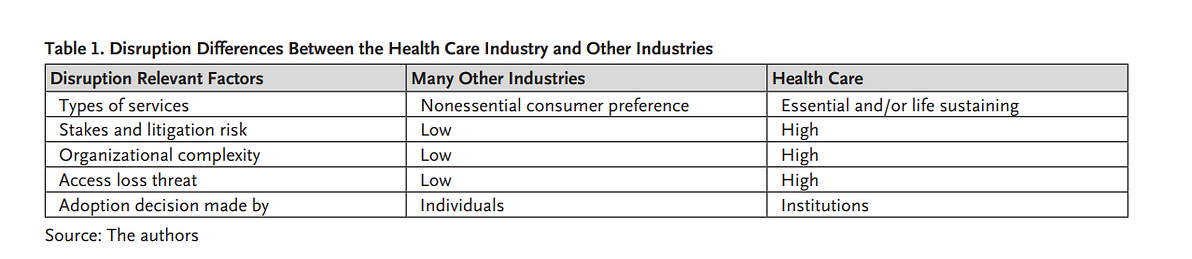

Essential health care services are characterized by high stakes, high complexity, high access loss threats, and decisions made at an institutional level. By contrast, disruptive innovations in other industries often occur in nonessential consumer preference services that are characterized by low stakes, low complexity, low access loss threats, and adoption decisions made by many independent individuals ( Table 1).

Differing Growth Trajectories: Netflix and Navitus

To illustrate how different the growth trajectories are in these two environments — essential/complex versus nonessential/simple services — we compare and contrast two innovative companies: Netflix, a disruptor in digital streaming services, and

Both are successful companies that brought a distinctive and improved business model to their industries. However, not all oligopolies are created — or disrupted — equally.

Netflix was founded in 1997 and began mailing DVDs directly to consumers’ homes. In short order, it sounded the death knell for video rental stores. Netflix then realized the potential of direct-to-consumer content and began disrupting another industry, cable television, through streaming services that provided much more targeted entertainment content directly to consumer audiences. Netflix has grown to provide services to more than 200 million subscribers globally each year and, at times, has been considered the largest entertainment company in the world by market capitalization.

How did Netflix grow so fast? Individual consumers make the decision to adopt the Netflix model. Institutions are not involved. Compared to many health care decisions, the stakes are low, as is the relative complexity. There are certainly no access loss threats either. Consumers can change services relatively easily at a low cost.

It’s a much steeper challenge to cause a similar type of disruption in health care. The stakes are high, as is the complexity. For a health care institution to switch to a start-up service provider, it takes much research, deep pockets, and an appetite for significant risk — and that last element is a dangerous factor in health care, where lives are at stake and an institutional decision could ultimately affect thousands, or even millions, of patients simultaneously.

Navitus was founded in 2003 when Dean Health Plan, headquartered in Madison, Wisconsin, led an effort to form a new type of PBM company to disrupt the market that, even back then, was already expensive and consolidated.

To break into such a difficult and complex market, Navitus employed a business model that was significantly different than other traditional PBMs. It introduced a fully transparent, 100% pass-through model that passes all of its achieved savings directly to its customers. Navitus also invested in technology that would allow its customers to see, at the claim level, exactly what their pharmaceutical costs and utilization patterns were — with no hidden fees or opaque rebate-sharing games.

According to Navitus internal operations data, it has maintained 98%+ customer retention over the last decade, and currently reports a customer Net Promoter Score (NPS) of 76. For reference, an NPS over 50 is considered excellent and 80 is considered world class. However, switching PBMs was very different from switching from Blockbuster or from cable television to Netflix, and the customer was different, too. In the PBM market, the choice of which PBM to use is made at an institutional level informed by teams of benefits consultants. The process of selecting and implementing a new PBM solution is very complex and often takes years for large clients.

The risk of introducing errors into patient medications, treatment regimens, or insurance benefits has to be considered very carefully. In addition, large employers (with thousands of employees across multiple states) or insurers (who cover millions of members coast to coast) have geographical coverage requirements that largely require PBMs to have national scale to even be considered as a legitimate contender. Therefore, even with a more transparent and lower-cost model, Navitus had to painstakingly build out a national-scale pharmacy and distribution network.

Unless we find a way to massively increase disruptive speed-to-scale ratios, we will likely continue to measure true, national-scale disruptive successes in quarter-centuries, not quarters.

Growth was slow, and key customers often were local businesses, school districts, and municipalities that didn’t require national networks from day one. In 2020, Costco Wholesaler (a global provider of goods and services that in FY 2021 reported $192 billion in net sales) acquired a minority interest in Navitus. As of June 2021, Navitus had about 950 employees, more than 750 clients, and was managing nearly $6 billion in annual drug spending for about 7.3 million people, and had contracts expected to add more than 1 million people within the next year or two. Those numbers were up from about 80 clients and 1 million people in 2010. As of March 2022, according to internal operations data, Navitus now serves more than 900 institutional clients representing 8.5 million members across all 50 States.

Still, as Christensen noted, disruption can take time. Despite its role as a disruptive innovator, after 19 years Navitus internal market share data indicates that it serves less than 3% of the total PBM market.

There are several nuanced reasons for this tied to the specific challenges of innovation in health care, and we will address two primary reasons:

First, complexity. PBM services, like many health care services, involve a lot more than just scalable technology services. Running a PBM requires deep expertise to set up nationwide pharmacy networks, ever-changing drug listings (formularies), clinical and utilization management criteria to help ensure appropriate use regimens, benefit design structures that determine what a member’s co-pays and other cost-sharing elements would be for a specific drug at multiple different pharmacy locations, and all of these variables potentially could differ across each drug, employer, and product type (i.e., Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, or commercial insurance). All of this, coupled with the need to continually adapt to evolving medical guidelines and interventions, negotiate and procure drugs at scale from hundreds of manufacturers, and adhere to millions of pages of governmental, insurance, and accreditation standards, make a traditional organic market entry extremely challenging.

Given these challenges, it’s easy to see why the status quo doesn’t change very often. Changes are complex, stakes are high, and loss of access to essential services is something that cannot be allowed to happen. That’s why the institutional purchasers frequently continue to choose to stay the course.

A second reason comes back yet again directly to oligopolies. Just as Navitus and a few other disruptive PBMs started to get to national scale after overcoming many significant barriers, a new strategic twist in the PBM market occurred. The largest PBMs and largest health insurers decided to merge — unfortunately, not in the form of disruptive collaboration, but rather in a defensive move that essentially removed from the open market some of the largest sources of covered lives from which the new disruptive PBMs could grow. It was a brilliant move benefiting a small group of shareholders, but a bad outcome for competition, and by extension, for the American public.

The above comparison illustrates a few major lessons:

- Nondisruptive collaboration approaches can continue to chip away against large, complex health care oligopolies, and these will continue to play an important role in the marketplace. However, unless we find a way to massively increase disruptive speed-to-scale ratios, we will likely continue to measure true, national-scale disruptive successes in quarter-centuries, not quarters.

- The types of services being disrupted, and the types of agents who are making the switching decisions, matter. When many independent individuals are making the decisions and the stakes and access risk threats are low, then the disruptions will almost always occur faster.

Therefore, to successfully compete with some of the largest oligopolies in health care, improved speed-to-scale is imperative.

In addition, mitigating the risk of access loss and moving to more scalable interventions must be addressed. Such institutional obstacles cannot be overcome by a single entrant. They require a collaborate to disrupt mindset between institutions -and a business model by which this disruption can be achieved.

The Health Care Utility Model: Rapidly Increasing Speed-to-Scale and Mitigating Risk

We define a health care utility as a self-sustaining nonstock corporation with a social mission, formed by health care institutions to provide essential products and services at the lowest sustainable cost, using a focused, transparent, and scalable business model.

Under this model, health care utilities work very differently than traditional businesses in that they are price minimizers, not margin maximizers. No one owns the company, the customers and funders are the same group, every customer gets the same low-cost terms, and there are significant positive market externalities that reach far beyond the products and services that are directly supplied by the health care utility into the broader subindustry that it disrupts.

We define a health care utility as a self-sustaining nonstock corporation with a social mission, formed by health care institutions to provide essential products and services at the lowest sustainable cost, using a focused, transparent, and scalable business model.

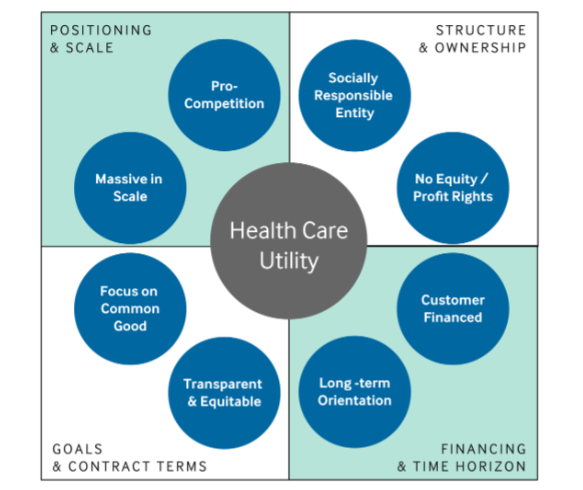

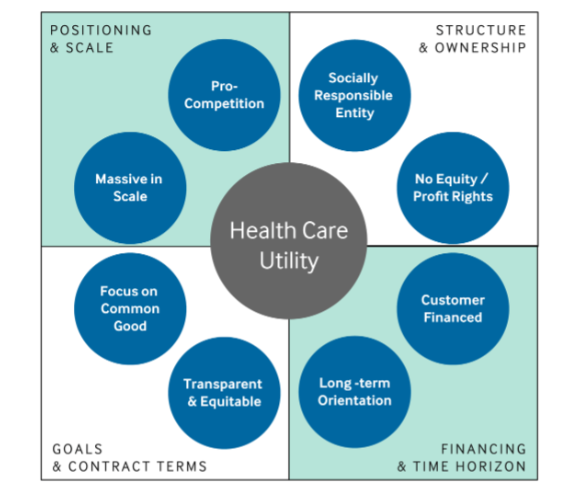

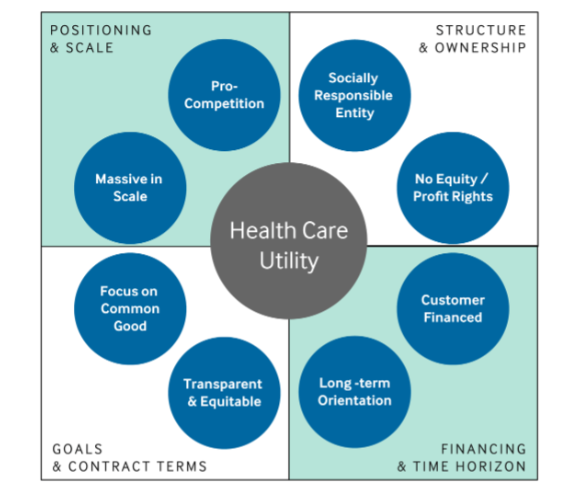

At a tactical level, health care utilities have eight key elements that can be aggregated into four broader categories: (1) structure and governance, (2) financing and time horizon, (3) goals and contract terms, and (4) market positioning and scale. Each of these elements and categories are now described.

Structure & Governance

This category articulates the principles related to how the business entity should be incorporated and governed. The primary structural option — to ensure the new entity acts as a socially responsible entity and functions without equity ownership/profit rights — is that of a nonstock, nonprofit corporation, ideally paired with an Internal Revenue Service-granted 501(c)(4) social welfare organization status. (Alternate structures, such as a Public Benefit LLC, are also options, with the right additional contractual adjustments.) This structure provides both tax advantages and enables private enterprise existence while technically still not being “owned” by anyone. These entities are, therefore, managed by stewards, commonly with philanthropists directly on the board to ensure long-term mission integrity.

Financing & Time Horizon

This category articulates how to fund and maintain the entity. The primary financing option to satisfy the customer financed condition is low-interest, long-term loans secured by assets of the new company that are provided directly by the customers who utilize the products or services of the utility. The desire is to garner the vast majority of the return on investment in the cost reductions of the products and services, not in the financing mechanism. This is in stark contrast to traditional private equity or venture capital financing models; this customer financing structure is one of the key defining features of the Health Care Utility Model.

Related to the long-term orientation condition, the ideal debt financing term length is between 10–20 years. This is long enough to meaningfully solve larger-scale social problems, but short enough to drive purposeful urgency. In terms of the long-term orientation for the entity itself, health care utilities are structured to exist in perpetuity with a financial break-even objective. While there is a need for a positive margin to continue to grow the business and replace existing assets over time, that margin will be kept very low as it is not inflated by shareholder return expectations and is continuously managed down by the customer/board members who are more focused on keeping costs sustainably low than driving margins unreasonably high. The goal is to make just enough to achieve the desired outcome.

Once funded, health care utilities can compete in ongoing fashion in the market. Grants and donations are also welcome, and these utilities are very attractive to potential philanthropists desiring to make large-scale social impact. However, the key is that these entities are not dependent on grants for their ongoing maintenance. This enables the entities to stay focused on the customer-defined problems to be solved in an agile operating model, not being subject to potential focus shifts from donors or potentially outdated administrative criteria from historical grants (see Appendix).

Goals & Contract Terms

This category articulates what types of problems these utilities are best at solving and what types of contracting strategies they use. Related to focusing on the common good, health care utilities are very good at scaling known innovations and addressing market failures — particularly when the failures are related to incentive misalignments or market aggregations that have negative impacts on patients.

Related to being transparent and equitable, health care utilities charge every member the same price for products and there are no special deals. This fully transparent and equitable pricing structure is the main reason why these businesses are called utilities — they deliver high-quality services to the masses at low, utility-like prices.

Positioning & Scale

This category articulates how these entities operate in terms of size and positioning in the market. Related to being massive in scale, these entities have the ability to achieve significant scale very quickly and then directly translate those scale benefits into lower prices for their customers. These utilities gain scale very quickly for numerous reasons:

- With multiple large and well-known incumbent institutions as founders, this provides near instantaneous purchasing scale and material credibility from day one.

- Because contract terms are the same for everyone, rapid sales cycles result.

- Due to nonstock ownership, membership growth is purely accretive as there is no ownership/earnings dilution when bringing on new partners. All growth adds accretive volume and spreads operating costs across a larger customer base — creating cost savings for all members.

- Because these businesses are access maximizers and cost minimizers, they are “difficult to hate” and easy to politically and socially support.

Related to being pro-competitive in nature, these entities are not government-run businesses. They must compete directly for customers in the marketplace. They are different than an association as they are operating entities that produce health care products and services directly, and remain competitive over time because their customers are on the board and thus have ongoing skin-in-the-game considerations to keep the entities focused on keeping costs in check.

These health care utility entities have the potential to open a new way of pursuing health care innovation — something akin to an “open source” health care movement: a nascent movement that could transcend heightened political and competitive divisions to accomplish revolutionary and meaningful change.

Looking Ahead

A big reason why health care is still stuck in a 20th-century model is because it is heavily populated by oligopolies — of all sorts and specializations — and these oligopolies are very hard to disrupt. Health care needs more competition. It also needs more collaboration.

To compete against these oligopolies, disruptive collaboration is a critical mindset, and the Health Care Utility Model is a key vehicle. When they are successfully combined and successively replicated across industry sectors, these health care utility entities have the potential to open a new way of pursuing health care innovation — something akin to an “open source” health care movement: a nascent movement that could transcend heightened political and competitive divisions to accomplish revolutionary and meaningful change. A movement more focused on people and care than profits and share. It is about a call to serve and to heal what’s broken — both clinically and administratively.

The Covid-19 pandemic has taught us many things in health care. From a positive perspective, it has shown us how much we can accomplish in a short time period when we all work together for a common objective of helping and healing one another. From a negative perspective, it has also taught us how staggeringly unequal access has become to multiple essential health care services.

The type of innovation we describe hearkens back to the days of the birth of many hospitals in the United States that were founded by communities and religious congregations who came together to accomplish something grander than any one individual could do alone, and to a time when the developers of early medicines dearly wanted their discoveries to remain inexpensive to the average consumer because the drugs provided such merciful relief from human suffering.

Large-scale disruption in health care is bound to happen eventually. What we need to decide is how long do we want it to take and whether the current incumbents will be the disruption facilitators or the barriers. Time will tell. But we are determined to level the playing field.

About the authors and affiliations

Carter Dredge, MHA

- Senior Vice President and Lead Futurist, SSM Health, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA

Dan Liljenquist, JD

- Senior Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer, Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

Stefan Scholtes, PhD

- Dennis Gillings Professor of Health Management and Director of the Centre for Health Leadership & Enterprise, Judge Business School, Cambridge University, United Kingdom

References and additional information

See the original publication

Originally published at https://catalyst.nejm.org on March 29, 2022.