This is a republication of the paper “4 Steps to Successful Value-Based Payment”, with the title above, highlighting the message in question.

Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform

Harold Miller

September 2022

Key messages by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

health transformation — journal

September 13, 2022

- It is time for payers to abandon pay-for-performance, shared-savings, and risk-based payment systems that have failed to improve quality or reduce spending, and instead …

- … work collaboratively with healthcare providers to design and implement effective value-based payment approaches that support high-quality care for patients at a more affordable cost.

- The most feasible and effective approach to accountability is for the physician, hospital, or other provider to agree that they will only bill the payer for the value-based payments if they have delivered the evidence-based services the payments were designed to support.

- In contrast to current pay-for-performance systems, this approach assures that each individual patient is receiving the most appropriate, high-quality care for their individual needs.

- It also eliminates the need for burdensome systems of attribution and measure reporting that significantly increase administrative costs for both providers and payers.

Introduction

Most value-based payment programs have failed to significantly reduce healthcare spending or improve the quality of care for patients.

Many have actually resulted in higher healthcare spending, and some have made it harder for patients with complex conditions to receive adequate care.

The reason current programs have failed is that payers have tried to create “incentives” for physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers to reduce spending without providing the resources and flexibility those providers need to improve the way they deliver services to their patients.

The solution is not to increase the financial risk for providers in these incentive programs, but to take a fundamentally different approach.

Value-based payment will only be successful if it is explicitly designed to support value-based care.

Providers deliver care, not payers, so value-based payments must be designed to ensure that providers are able to deliver high-value services to their patients.

Value-based payment will only be successful if it is explicitly designed to support value-based care.

Providers deliver care, not payers, so value-based payments must be designed to ensure that providers are able to deliver high-value services to their patients

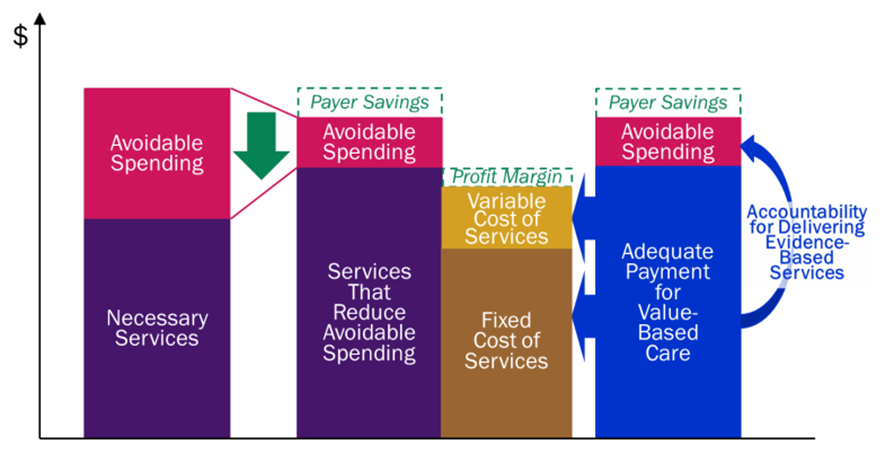

Four steps are needed to achieve this:

1. Identify “potentially avoidable spending,” i.e., specific types of healthcare services or spending that could be reduced without harming patients;

2. Design an approach to delivering services that is expected to reduce the avoidable spending;

3. Create payments that give providers the ability to implement and sustain the new approach to service delivery; and

4. Hold providers accountable for delivering appropriate, evidence-based services in return for the value-based payments.

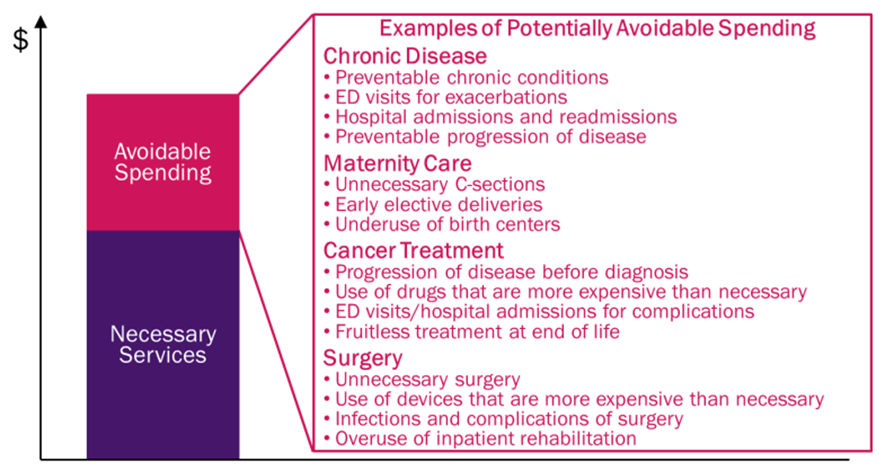

Step 1: Identify Specific Types of Potentially Avoidable Spending

Step 1 is for physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers to identify the subset of current spending for their patients that is potentially avoidable.

There are two major categories of avoidable spending:

· Planned Care. Avoidable spending in this category includes things like ordering or delivering unnecessary tests, medications, or procedures, and using expensive tests and treatments when a less-expensive and equally effective alternative is available. In some cases, the unnecessary services can be harmful to the patient as well as resulting in higher spending.

· Unplanned Care. Avoidable spending in this category includes things such as Emergency Department (ED) visits and hospitalizations for preventable exacerbations of a chronic disease, and treatments for new health problems that could have been prevented from developing. These services are necessary at the time they are delivered, but the circumstances that resulted in the need for the services could have been avoided if care had been delivered in a different way at an earlier point in time.

A number of studies have shown there is a large amount of avoidable spending in the healthcare system overall.

However, the specific types and amounts of avoidable spending will differ for different patients, different health conditions, and different healthcare providers, and it will change over time as new treatments are developed.

For example,

· the largest category of avoidable spending for some types of chronic conditions is hospitalizations for exacerbations;

· for other chronic conditions, a bigger opportunity for savings is reducing the use of medications that are more expensive than necessary;

· and for some conditions, there is relatively little avoidable spending.

Payers cannot simply assume that healthcare providers will be able to reduce spending on their patients by an arbitrary amount; a careful analysis of current services and patient needs is required in order to determine what is actually feasible.

Payers cannot simply assume that healthcare providers will be able to reduce spending on their patients by an arbitrary amount; a careful analysis of current services and patient needs is required in order to determine what is actually feasible.

Step 1: Identify Specific Types of Potentially Avoidable Spending

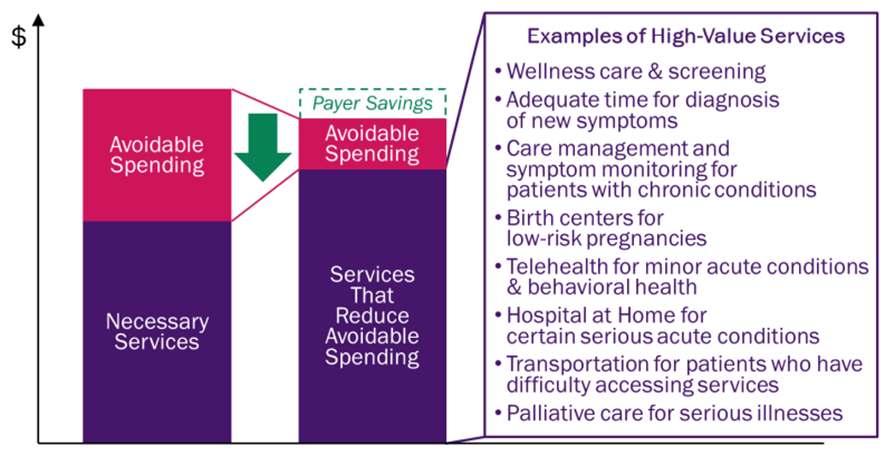

Step 2: Design Services That Will Reduce the Avoidable Spending

Step 2 is for physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers to design a different approach to delivering services to their patients that they believe will reduce the specific types of avoidable spending that were identified in Step 1.

In most cases, reducing avoidable spending is not simply a matter of delivering fewer services.

In general, at least one new or different service must be delivered to a patient instead of the service(s) that will be reduced. For example:

· in order for patients with chronic conditions to avoid the exacerbations that result in ED visits and hospitalizations, they may need to receive more assistance in managing their condition or they may need different medications or treatments.

· in order for a physician to avoid ordering an unnecessary or unnecessarily-expensive test or procedure, they may need to spend more time with the patient to narrow the range of potential diagnoses for a symptom or to help the patient decide to pursue a different method of treatment.

Also, a lower-cost treatment has to be available and affordable for the patient, otherwise it is not realistic to expect it to be used.

· in order to prevent a patient from developing new health problems, a physician practice may need to provide more assistance to the patient in maintaining or improving their health and in obtaining appropriate screenings for cancer and other conditions.

In most cases, reducing avoidable spending is not simply a matter of delivering fewer services.

In general, at least one new or different service must be delivered to a patient instead of the service(s) that will be reduced.

Step 2: Design Services That Will Reduce Avoidable Spending

Every medical specialty has developed evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) that indicate what types of tests, medications, and procedures are appropriate for specific types of patients and what types of services are likely to reduce avoidable complications and prevent health problems from occurring.

Many patients are not receiving services consistent with these guidelines, so an obvious place to start in reducing avoidable spending is to develop ways to increase the use of appropriate, evidence-based services.

Every medical specialty has developed evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) … Many patients are not receiving services consistent with these guidelines

On the other hand, for many types of patients, there is no clear evidence as to what services will achieve the best outcomes.

A value-based payment program cannot simply assume that healthcare providers will be able to reduce spending that is potentially avoidable if there is no clear evidence as to how services should be delivered in a way that would achieve that result.

Moreover, the only way such evidence can be developed may be to provide payments that support testing of new approaches to care delivery so their impacts on spending and outcomes for patients can be evaluated.

On the other hand, for many types of patients, there is no clear evidence as to what services will achieve the best outcomes. … the only way such evidence can be developed may be to provide payments that support testing of new approaches …

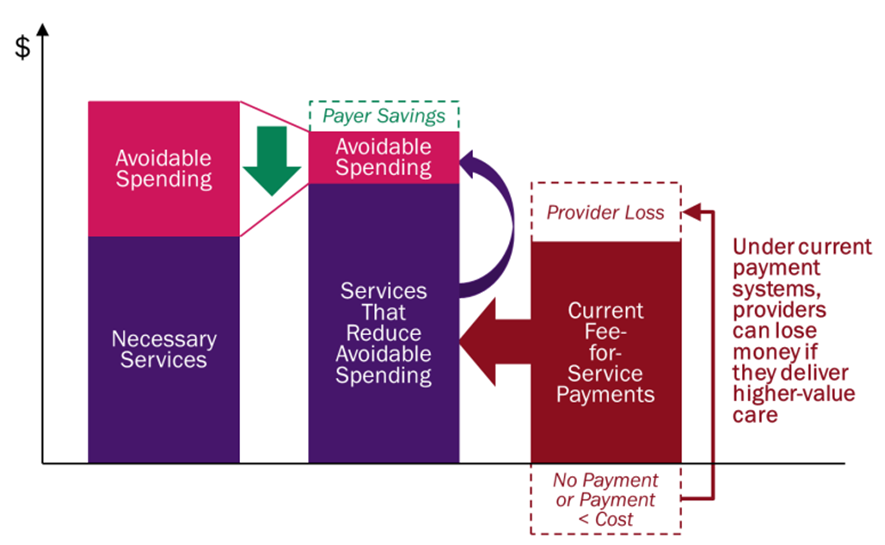

Step 3: Pay Adequately to Support Higher-Value Services

Step 3 is for payers to change their payments in a way that will enable providers to implement the care delivery approach developed in Step 2.

If an evidence-based approach to care delivery exists but is not being used by providers, it is often because current payment systems create barriers to doing so.

If an evidence-based approach to care delivery exists but is not being used by providers, it is often because current payment systems create barriers to doing so.

These barriers generally fall into two categories:

· No payment for services.

· Inadequate payment for services.

a) No payment for services.

Even though current payment systems include fees for over 15,000 different services, there are no payments at all for many high-value services that could reduce avoidable spending, such as

· time spent by nurses educating patients about how to manage their health problems,

· non-medical services such as transportation to outpatient service sites, and

· palliative care services for patients with advanced illnesses.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, most payers did not pay for telehealth services to patients in their homes, despite the obvious value of that approach to care in many circumstances.

Current Payments Do Not Support Value-Based Care

b) Inadequate payment for services.

For most medical services, a high percentage of the cost of delivering the service is a fixed cost for the provider, i.e., the cost does not change when fewer services are delivered. This includes the core staff of a physician practice or hospital, not just the capital cost of equipment and facilities.

When much of the cost is fixed, the total cost of delivering services will not decrease in direct proportion to a reduction in the volume of services delivered, and the average cost of delivering an individual service will increase when fewer of those services are delivered.

Under standard fee-for-service payment systems, however, revenues decrease in direct proportion to volume, which may make it impossible for providers to cover their costs when fewer services are delivered.

If a value-based payment program does not remove these barriers, physicians, hospitals, and other providers will be unable to deliver services in a way that will reduce avoidable spending for their patients.

Merely creating bonuses and penalties for providers will not be effective because the problem is not that providers need an incentive to deliver better care to their patients, but instead that they are unable to do so because of limitations in the current payment system.

Under standard fee-for-service payment systems, however, revenues decrease in direct proportion to volume, which may make it impossible for providers to cover their costs when fewer services are delivered.

If a value-based payment program does not remove these barriers, physicians, hospitals, and other providers will be unable to deliver services in a way that will reduce avoidable spending for their patients.

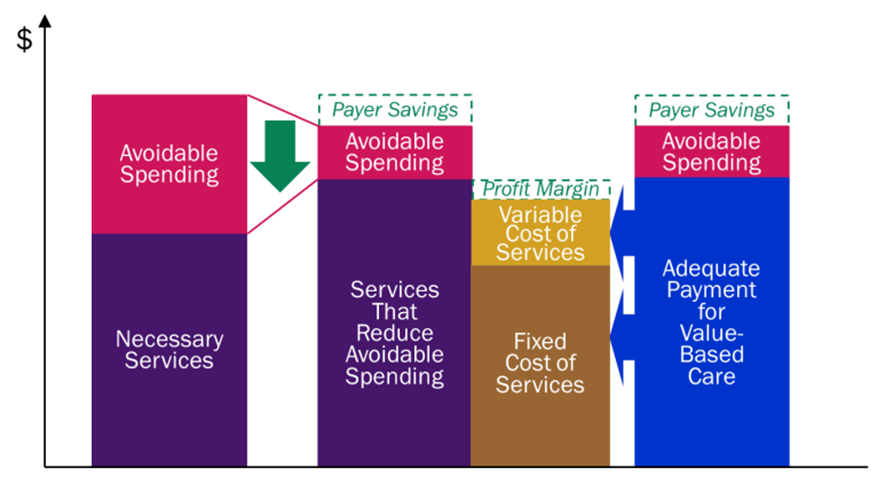

Determining the Cost of Value-Based Care

In order for value-based payments to be adequate to support the services required for higher-value care, one has to know what it will cost to deliver those services.

Payers cannot determine this from health insurance claims data, since the amount an insurance plan pays for a service may be higher or lower than what it costs a provider to deliver that service.

If a service is not being delivered today because there is no payment at all, it will be difficult to know for sure what the service will cost until after it is actually being delivered.

Moreover, even if the current payment amount matches the current cost of a service, that cost will likely change in the future if the service is delivered more or less frequently in order to reduce avoidable spending.

For example, value-based care initiatives that are designed to reduce avoidable hospitalizations or unnecessary procedures can fail if the payments to the hospital for the subset of patients who still need hospital care are not adequate to cover the costs of delivering those services.

Cost accounting systems and methodologies such as Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) can provide information on what it currently costs to deliver existing services, but not what it will cost to deliver care differently in the future when a new, value-based approach to care is being used.

In order to set value-based payment amounts correctly, providers need to create a cost model that identifies the fixed and variable costs associated with services and estimates how those costs will change when there are changes in the number of services delivered.

Cost accounting systems and methodologies such as Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) can provide information on what it currently costs to deliver existing services, but not what it will cost to deliver care differently in the future when a new, value-based approach to care is being used.

In order to set value-based payment amounts correctly, providers need to create a cost model that identifies the fixed and variable costs associated with services and estimates how those costs will change when there are changes in the number of services delivered.

Step 3: Pay Adequately to Support Higher-Value Services

Creating a Business Case for Change

In most cases, the savings from reductions in avoidable services will be large enough to offset any increase in payments needed to support the cost of delivering evidence-based services, which means there is a business case for a payer to make the changes in payments.

If the value-based approach to care will cost more for providers to deliver, but the savings from reducing avoidable spending will be less than the increase in cost, the providers should

· look for ways to deliver the associated services more efficiently or

· to increase the expected reduction in avoidable spending. (More details and an example of this are available in Making the Business Case for Payment and Delivery Reform.)

For some patients, such as those with complex conditions, a net increase in spending may be necessary to deliver the services required to achieve good health outcomes.

It will be easier to afford this if aggressive efforts are also made to improve care in areas where a net reduction in spending can be achieved.

Fees vs. Bundles vs. Capitation

In addition to determining the amount of payment providers will need, a method for delivering the payments to the providers will be required.

There is no one “best” method of paying providers for delivering value-based care.

Fee-for-service payment has many strengths as well as weaknesses, and capitation payments have serious weaknesses as well as some advantages.

In addition to determining the amount of payment providers will need, a method for delivering the payments to the providers will be required

In many cases, the simplest method for supporting the delivery of value-based care will be to create a fee for a new service or to increase the fee for an existing service.

In other cases, it may be desirable to replace existing fees with a “bundled” payment that provides the flexibility to deliver services in different ways.

The approach chosen should be one that is easy for both providers and payers to implement and that providers believe will enable them to deliver the services identified in Step 2.

Step 4: Take Accountability for Delivering Evidence-Based Care

Step 4 is for the providers receiving the new payments to take accountability for delivering services to their patients in the way that is expected to reduce the avoidable spending.

If the payments created in Step 3 are adequate to support the delivery of the services defined in Step 2, and if a physician, hospital, or other healthcare provider has agreed to deliver services to its patients in that way, it is reasonable for a payer to expect the provider to do so in return for receiving the value-based payments.

Step 4: Providers Take Accountability for Delivering Evidence-Based Care

In theory, it would be desirable for providers to take accountability through an “outcome-based payment,” i.e., only being paid if the avoidable spending is reduced.

However, in practice, this is usually infeasible for several reasons:

· Unplanned care, such as hospital admissions for chronic disease exacerbations or treatments for new health problems, results from a variety of patient-specific factors, only a subset of which can be controlled by a physician or other healthcare provider.

· The costs of planned care can increase for reasons beyond the control of healthcare providers.

For example, if a new treatment becomes available that is significantly more effective but also more expensive, a physician should not be precluded from ordering or providing that treatment simply because it would reduce the savings they had been expected to achieve.

In addition, unexpectedly large increases in the prices of drugs or wages for healthcare workers may reduce the amount of savings that had been expected from substituting lower-cost treatments for higher-cost approaches.

· The reduction in avoidable spending may occur long after the value-based services are delivered, and providers cannot afford to wait to be paid for their services until after those outcomes are achieved.

In theory, it would be desirable for providers to take accountability through an “outcome-based payment,” i.e., only being paid if the avoidable spending is reduced.

However, in practice, this is usually infeasible for several reasons

Pay-for-performance systems that pay bonuses or penalties based on quality measures are also problematic because the quality measures that are typically used don’t measure the true quality of care and they can penalize providers that care for higher-need patients. (These problems are explained in more detail in Why Quality Measures Don’t Measure Quality.)

The worst approach is putting providers at financial risk for total healthcare spending on their patients, as Medicare and other payers have tried to do.

No one can predict exactly what services a group of patients will need, and no physician, hospital, or accountable care organization can control the costs of all of those services.

The worst approach is putting providers at financial risk for total healthcare spending on their patients, as Medicare and other payers have tried to do. …

No one can predict exactly what services a group of patients will need, and no physician, hospital, or accountable care organization can control the costs of all of those services.

Risk-based payment and global capitation can increase disparities in healthcare access and outcomes by penalizing providers when they care for sicker and more complex patients, and it can also cause consolidation of providers and higher prices. (More detail on these problems is available in 5 Fatal Flaws in Total Cost of Care & Population-Based Payment Models.)

Risk-based payment and global capitation can increase disparities in healthcare access and outcomes by penalizing providers when they care for sicker and more complex patients, and it can also cause consolidation of providers and higher prices.

The Wrong Approach: Putting Providers at Risk for Costs They Cannot Control

The most feasible and effective approach to accountability is for the physician, hospital, or other provider to agree that they will only bill the payer for the value-based payments if they have delivered the evidence-based services the payments were designed to support.

If the provider has to deviate from evidence-based guidelines for patient-specific reasons (e.g., the patient was unwilling or unable to use the evidence-based treatment), the provider would need to document those reasons in the patient’s clinical record in order to be paid for the services that were delivered.

The most feasible and effective approach to accountability is for the physician, hospital, or other provider to agree that …

… they will only bill the payer for the value-based payments if they have delivered the evidence-based services the payments were designed to support.

In contrast to current pay-for-performance systems, this approach assures that each individual patient is receiving the most appropriate, high-quality care for their individual needs.

It also eliminates the need for burdensome systems of attribution and measure reporting that significantly increase administrative costs for both providers and payers.

In contrast to current pay-for-performance systems, this approach assures that each individual patient is receiving the most appropriate, high-quality care for their individual needs.

It also eliminates the need for burdensome systems of attribution and measure reporting …

A Win-Win-Win Approach to Value-Based Payment

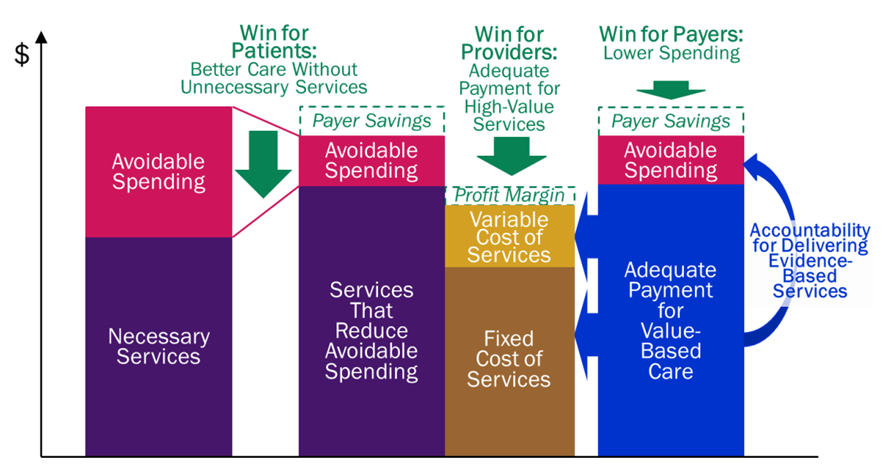

If value-based payment is designed through the steps described above, it can be a “win-win-win” for patients, providers, and payers:

· Patients win by receiving the care they need to address their health problems, not receiving unnecessary services that are expensive or harmful, and avoiding complications and other undesirable outcomes.

· Providers win by being able to deliver the services their patients need. They will not lose money when they deliver high-quality care nor will they make high profits by delivering unnecessary services or allowing preventable complications to occur.

· Payers win by paying no more than is necessary in order for patients to receive high-quality care, which will enable the payers to offer insurance at the most affordable cost.

A number of physicians, medical specialty societies, and other organizations have developed these types of value-based payments to support better care for patients with conditions such as asthma, cancer, headache, ischemic heart disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and pregnancy, and for providers ranging from primary care practices to emergency physicians and palliative care teams.

It is time for payers to abandon pay-for-performance, shared-savings, and risk-based payment systems that have failed to improve quality or reduce spending, and instead work collaboratively with healthcare providers to design and implement effective value-based payment approaches that support high-quality care for patients at a more affordable cost.

It is time for payers to abandon pay-for-performance, shared-savings, and risk-based payment systems that have failed to improve quality or reduce spending, and instead …

work collaboratively with healthcare providers to design and implement effective value-based payment approaches that support high-quality care for patients at a more affordable cost.

Value-Based Payment Can Be a Win-Win-Win for Patients, Providers, and Payers

Originally published at: https://chqpr.org