Site editor:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

The Health Transformation — Content Platform

September 30, 2022

World Heart Federation

27 Aug 2022

Informing health systems approaches to CVD by prioritizing practical, proven, cost-effective action

Health systems face fundamental challenges in delivering optimal care due to ageing populations, constraints in their healthcare workforce, financing, availability and affordability of cardiovascular disease (CVD) medicine, and service delivery. Therefore, patient self-care and empowerment are becoming increasingly important.

Digitalization has revolutionalised the way we communicate, inform ourselves, shop, and, to some extent, interact with the healthcare system.

Despite a good understanding of the potential of digital technology for health, various societal and professional constraints have delayed uptake in both high- and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Digital health interventions (DHI), which include text message programmes, mobile (mHealth) apps, telehealth consultations, wearable devices, and electronic decision support tools, have the potential to help improve this.

The COVID-19 pandemic has sped up the use of digitalization in healthcare and the use of DHI due to a fear of contracting COVID-19 in a medical facility, or because of the facility’s overload, patients have — quite effectively — had consultations via mobile phone or via internet.

Similarly, doctors have equipped patients with monitoring devices and treatments for at-home use.

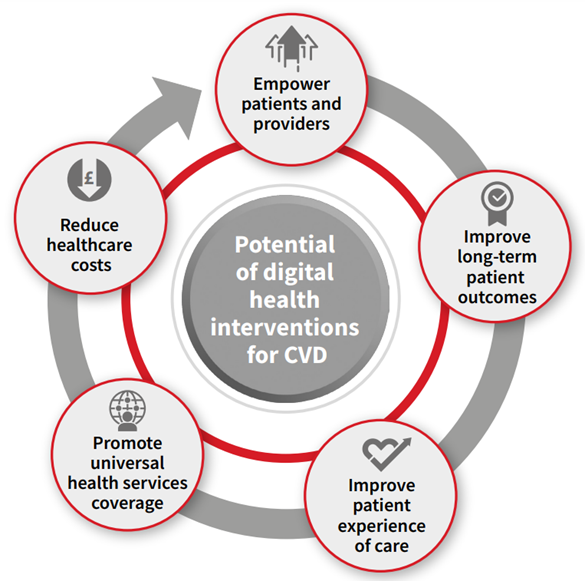

These technologies can contribute to Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by empowering patients[1] and providers,[2] enabling universal health services coverage,[3] improving long-term patient outcomes and care experience, and reducing healthcare costs[4] (figure 1).

Figure 1: The potential of digital health interventions for CVD

In 2020, there were an estimated 6.95 billion mobile phone and 3.5 billion smartphone users worldwide.[5]

These major and rapid advances in internet and mobile technology, including in LMICs, bear an enormous potential to expand the reach of healthcare and reduce the burden of CVD.

DHI may be a tool to reach Sustainable Development Goal 3.4 and reduce premature mortality from NCDs by a third by 2030.[6]

In 2020, the World Heart Federation (WHF) published a position paper “The Case for the Digital Transformation of Circulatory Health”[7] as an outcome of the 4th Global Summit on Circulatory Health, held in Paris on 29–30 August 2019.

To build on this, WHF has developed a Roadmap for digital cardiology to support WHF Members in engaging actively with national stakeholders to implement digital health at the country level to improve the prevention and management of CVD.

The Roadmap sets out to identify solutions to overcome roadblocks and leverage digital tools to increase access to cardiovascular prevention, management and care.

Today, a range of factors hinder the implementation and access to digital health technologies globally. They pertain to:

· Health system governance (e.g., national privacy regulations and internet access),

· health providers (e.g., digital literacy, perceived effectiveness),

· patient (e.g., age, local sex/gender norms, socioeconomic factors, digital and health literacy), and

· technology (e.g., a context-specific adaptation of technology, interoperability).

THE ROLE DIGITAL HEALTH CAN PLAY IN PREVENTING AND MANAGING CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Several DHIs have shown potential for managing CVD, including text message programmes, mobile (mHealth) apps, telehealth consultations, wearable devices, and electronic decision support tools.[8]

· Mobile Health Interventions

· Telehealth

· Wearable Devices

· Electronic Decision Support Tools

1.MOBILE HEALTH INTERVENTIONS

Personalised messages to patients can assist management of CVD risk factors such as tobacco smoking,[9] high blood pressure,[10] physical activity,[11] weight management,[12] and medication adherence.[13] [14]

The success of the messaging is often because of the co-design of text content with patients and clinicians, using techniques from behavioural psychology.[15]

Similarly, mobile (mhealth) apps can reduce rehospitalisations, improve patient knowledge, quality of life, and psychosocial well-being, and help manage CVD risk factors.

2.TELEHEALTH

The use of telehealth improves access to CVD treatment by ensuring constant communication between patients and their health providers, and ensuring timely monitoring and remote counselling that support CVD management.

3.WEARABLE DEVICES

Wearable technology accessibility has improved, and so have its capabilities to enhance CVD management and prevention.

Wearable devices are known to increase daily steps and energy expenditure compared to people not using wearable devices.[16]

Wearable devices can go beyond counting calories to measuring one’s blood pressure and heart rate by transmitting biophysical measurements and patient-generated data to physicians.

Potential detection of hypertension and atrial fibrillation through wearable devices has the potential to prevent or better manage CVD.[17]

4.ELECTRONIC DECISION SUPPORT TOOLS

Clinicians use various clinical electronic decision support tools to manage CVD conditions.

Promising results from a recent heart failure trial showed an alerting system using electronic health records (EHR) could improve the use of medication to treat heart failure.[18]

Clinicians can also use artificial intelligence (AI) to aid in interpreting medical images.

ROADBLOCKS AND SOLUTIONS TO IMPLEMENT DIGITAL HEALTH INTERVENTIONS

Ideal conditions for implementing digital health technologies are often not met.

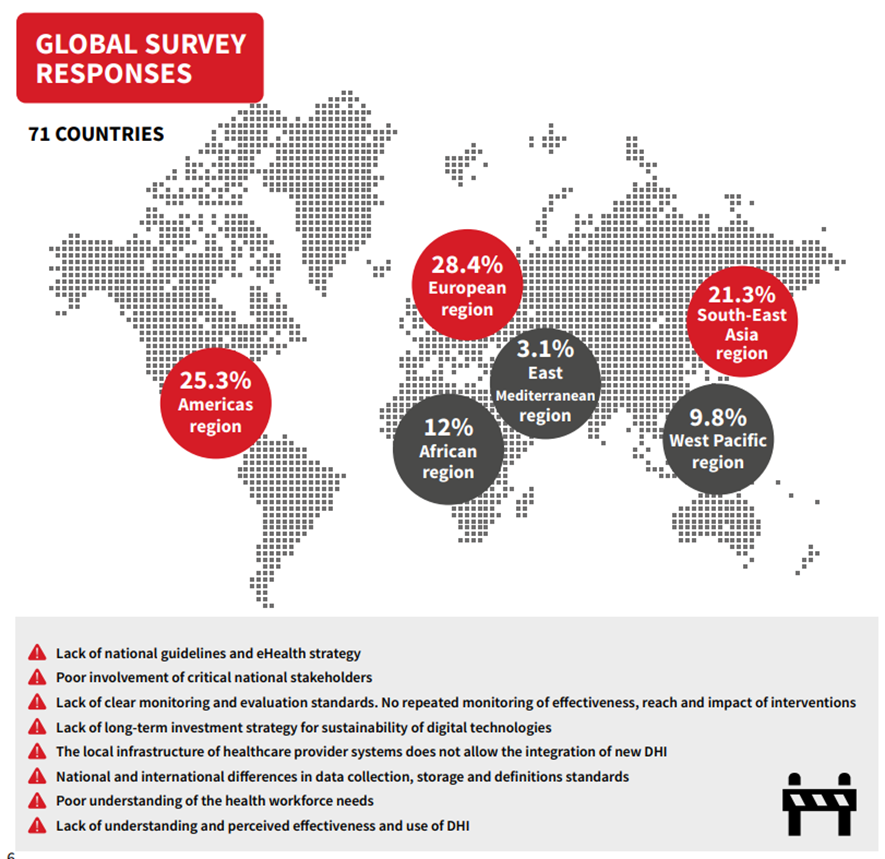

The success of a national eHealth environment relies on good leadership and governance, high-quality legislation and policies, a clear investment and reimbursement strategy, high-quality services and applications, a supporting digital health infrastructure, clear interoperability and data standards and a tech-savvy workforce as outlined in the adapted WHO/ITU framework[19] (figure 2), that also includes patient-level barriers.

Figure 2: Selected roadblocks and solutions to implement digital health interventions, based on the WHO/ITU framework

ROADBLOCKS TO IMPLEMENTING DIGITAL HEALTH INTERVENTIONS

A global survey of WHF Membership organisations gathered data related to roadblocks and solutions to implementing DHIs.

In total, 227 participants from 71 countries completed the survey. The European region made up 28.4% of the responses collected; 25.3% in the Americas, 21.3% in South-East Asia, 12% in the African Region, 9.8% in the western Pacific and 3.1% in the Eastern Mediterranean regions. Furthermore, 35% were from high-income countries, 60% from middle-income countries and 15% from low-income countries.

BOX: Roadblocks

· Lack of national guidelines and eHealth strategy

· Poor involvement of critical national stakeholders Lack of clear monitoring and evaluation standards.

· No repeated monitoring of effectiveness, reach and impact of interventions

· Lack of long-term investment strategy for sustainability of digital technologies

· The local infrastructure of healthcare provider systems does not allow the integration of new DHI

· National and international differences in data collection, storage and definitions standards

· Poor understanding of the health workforce needs

· Lack of understanding and perceived effectiveness and use of DHI

SOME SOLUTIONS TO OVERCOME ROADBLOCKS

· Establish national or regional eHealth guidelines and strategies

· Inclusive engagement with stakeholders by policymakers, including representatives of patients, practitioners, payers, industry and civil society

· Clear national standards for monitoring and evaluation of DHIs. Long-term monitoring of effectiveness and implications of digital health interventions. ‘unexpected effects’ registry

· Explicit national guidelines on data access and security.

· Promote harmonisation of policies between institutions

· Clear reimbursement strategy for DHI. Include economic evaluations in the design phase

· Include long-term investment strategy as part of national guidelines

· Employ user-centred and co-design principles.

· Include end-users (practitioners/patients) early in the design phase

· Investing in digital health infrastructure should be included as a national policy priority

· Applications should be flexible and available in on- and offline modes

· Promote collective definitions and data storage formats with an emphasis on the implementation of open data platforms

· Include clear health system and needs assessment in the design phase of DHIs

· Provider education on the use of digital technology

· Inclusive technology design and education of use

· Patient education on the use of digital technology, context-specific adaptations of technology to match patients’ physical abilities

· Inclusive technology design, education of use and user acceptance, usefulness and engagement evaluation alongside clinical trials and related research.

PRACTICAL EXAMPLE 1

CONNECT: A CONSUMER-FOCUSED, RESPONSIVE AND PRIMARY CAREINTEGRATED WEB-APPLICATION

The Consumer Navigation of Electronic Cardiovascular Tools (CONNECT) intervention is a consumer-focused, responsive web application. It is interactive and integrated with data from the patient’s primary care electronic health record. It was co-designed with consumers, clinicians and software developers.

CONNECT includes digital reminders and access to:

· Information about medical conditions, information on medicines and interactive absolute risk awareness (red tiles);

· goal-setting, progress tracking and virtual rewards (green tiles);

· polling for interactivity and social interaction (blue tiles).

PRACTICAL EXAMPLE 2

MPOWER HEALTH: A CLINICAL DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM FOR EVIDENCE-BASED CARE

MPOWER HEART WORKS ON TWO CORE PRINCIPLES:

1. Technology (a knowledge-based Clinical Decision Support System-CDSS)

· A mobile app for healthcare providers and a web-based dashboard/ server for healthcare administration

· Clinical Decision Support System generates personalised management plans for patients with hypertension and diabetes

· Computing clinical risk scores

· Maintaining longitudinal health records of the patient

· Ability to work in offline mode (without internet connectivity)

· Real-time monitoring and profile visualiser for trending and quick decision making.

2. Task-shifting

· Empowering the non-physician workforce to deliver quality care by using technology

· Generating lifestyle recommendations tailored to individual patients.

References and additional information:

See the original publicati

Originally published at: https://world-heart-federation.org