The Economist

Aug 11th 2022

Site editor:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Health Management Matters

multidisciplinary institute, digital journal and content platform

October 8, 2022

Physical labour is exhausting.

A long run or a hard day’s sweat depletes the body’s energy stores, resulting in a sense of fatigue.

Mental labour can also be exhausting.

Even resisting that last glistening chocolate-chip cookie after a long day at a consuming desk job is difficult.

Cognitive control, the umbrella term encompassing mental exertion, self-control and willpower, also fades with effort.

But unlike the mechanism of physical fatigue, the cause of cognitive fatigue has been poorly understood.

Cognitive control, the umbrella term encompassing mental exertion, self-control and willpower, also fades with effort. But unlike the mechanism of physical fatigue, the cause of cognitive fatigue has been poorly understood.

Previous accounts were incomplete.

One of the most widely known, the biological one, draws from what is known about muscular fatigue.

It posits that exerting cognitive control uses up energy in the form of glucose.

At the end of a day spent intensely cogitating, the brain is metaphorically running on fumes.

The problem with this version of events is that the energy cost associated with thinking is minimal.

One analysis of previous studies suggests that cognitively overworked and “depleted” brains use less than one-tenth of a Tic-Tac’s worth of additional glucose.

One analysis of previous studies suggests that cognitively overworked and “depleted” brains use less than one-tenth of a Tic-Tac’s worth of additional glucose.

If cognitive fatigue is not caused by a lack of energy, then what explains it?

A team of scientists led by Antonius Wiehler of Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital, in Paris, looked at things from what is termed a neurometabolic point of view.

They hypothesise that cognitive fatigue results from an accumulation of a certain chemical in the region of the brain underpinning control.

That substance, glutamate, is an excitatory neurotransmitter that abounds in the central nervous systems of mammals and plays a role in a multitude of activities, such as learning, memory and the sleep-wake cycle.

They hypothesise that cognitive fatigue results from an accumulation of a certain chemical in the region of the brain underpinning control.

In other words, cognitive work results in chemical changes in the brain, which present behaviourally as fatigue.

This, therefore, is a signal to stop working in order to restore balance to the brain.

In other words, cognitive work results in chemical changes in the brain, which present behaviourally as fatigue.

This, therefore, is a signal to stop working in order to restore balance to the brain.

In their new paper in Current Biology, the researchers describe an experiment they undertook to explain how all this happens.

To induce cognitive fatigue, a group of participants were asked to perform just over six hours of various tasks that involve thinking.

Half were assigned easy things to do and half hard ones.

For example, in one task, letters were displayed on a computer screen every second or so.

Those in the easy group had to remember whether the current letter matched the previous letter or, for the hard group, the one shown three letters earlier.

Periodically, throughout the experiment, participants were asked to make decisions that could reveal their cognitive fatigue.

They might be asked whether they would want to earn €50 ($52) for cycling on an exercise bike for 30 minutes at power level six (a high-cost, high-reward task) or €37 for 30 minutes at power level two (low-cost, low-reward).

Participants who were assigned the more challenging cognitive-control tasks were more likely to opt for the low-cost, low-reward options, especially towards the end of the six hours.

In addition, the hard-task participants invested less effort in making that decision.

Their eyes were the clue.

The pupil initially constricts when participants are shown the two options.

The time it takes for the pupil to subsequently dilate reflects the amount of mental exerted.

The pupil-dilation times of participants assigned hard tasks fell off significantly as the experiment progressed.

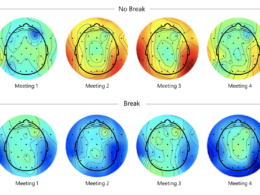

During the experiment the scientists used a technique called magnetic-resonance spectroscopy to measure biochemical changes in the brain.

In particular, they focused on the lateral prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain associated with cognitive control.

If their hypothesis was to hold, there would be a measurable chemical difference between the brains of hard- and easy-task participants. And indeed, that is what they found.

Their analysis indicated higher concentrations of glutamate in the synapses of a hard-task participant’s lateral prefrontal cortex.

Thus showing cognitive fatigue is associated with increased glutamate in the prefrontal cortex.

Thus showing cognitive fatigue is associated with increased glutamate in the prefrontal cortex.

Dr Wiehler speculates that this is the result of a mechanism in the brain that is computing a sort of cost-benefit analysis, with fatigue and increased glutamate adding to the cost of mental effort.

There may well be ways to reduce the glutamate levels,

… and no doubt some researchers will now be looking at potions that might hack the brain in a way to artificially speed up its recovery from fatigue.

Meanwhile, the best solution is the natural one: sleep.

Meanwhile, the best solution is the natural one: sleep.

Originally published at https://www.economist.com on August 11, 2022.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

A neuro-metabolic account of why daylong cognitive work alters the control of economic decisions

Current Biology

AntoniusWiehler 1234673

FrancescaBranzoli 23

IsaacAdanyeguh 3

FannyMochel 35

MathiasPessiglione 1234

22 August 2022

Highlights

- Cognitive fatigue is explored with magnetic resonance spectroscopy during a workday

- Hard cognitive work leads to glutamate accumulation in the lateral prefrontal cortex

- The need for glutamate regulation reduces the control exerted over decision-making

- Reduced control favors the choice of low-effort actions with short-term rewards

Summary

- Behavioral activities that require control over automatic routines typically feel effortful and result in cognitive fatigue.

- Beyond subjective report, cognitive fatigue has been conceived as an inflated cost of cognitive control, objectified by more impulsive decisions.

- However, the origins of such control cost inflation with cognitive work are heavily debated.

- Here, we suggest a neuro-metabolic account: the cost would relate to the necessity of recycling potentially toxic substances accumulated during cognitive control exertion.

- We validated this account using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to monitor brain metabolites throughout an approximate workday, during which two groups of participants performed either high-demand or low-demand cognitive control tasks, interleaved with economic decisions.

- Choice-related fatigue markers were only present in the high-demand group, with a reduction of pupil dilation during decision-making and a preference shift toward short-delay and little-effort options (a low-cost bias captured using computational modeling).

- At the end of the day, high-demand cognitive work resulted in higher glutamate concentration and glutamate/glutamine diffusion in a cognitive control brain region (lateral prefrontal cortex [lPFC]), relative to low-demand cognitive work and to a reference brain region (primary visual cortex [V1]).

- Taken together with previous fMRI data, these results support a neuro-metabolic model in which glutamate accumulation triggers a regulation mechanism that makes lPFC activation more costly, explaining why cognitive control is harder to mobilize after a strenuous workday.

Cite this article

Antonius Wiehler, Francesca Branzoli, Isaac Adanyeguh, Fanny Mochel, Mathias Pessiglione, A neuro-metabolic account of why daylong cognitive work alters the control of economic decisions, Current Biology, Volume 32, Issue 16, 2022, Pages 3564–3575.e5, ISSN 0960–9822,

Originally published at: https://www.sciencedirect.com