NEJM

Véronique Bouvard, Ph.D., Suzanne T. Nethan, M.D.S., Deependra Singh, Ph.D., Saman Warnakulasuriya, Ph.D., Ravi Mehrotra, M.D., Ph.D., Anil K. Chaturvedi, M.P.H., Ph.D., Tony Hsiu-Hsi Chen, Ph.D., Olalekan A. Ayo-Yusuf, M.P.H., Ph.D., Prakash C. Gupta, Ph.D., Alexander R. Kerr, D.D.S., Wanninayake M. Tilakaratne, Ph.D., Devasena Anantharaman, Ph.D., David I. Conway, D.P.H., Ph.D., Ann Gillenwater, M.D., Newell W. Johnson, F.Med.Sci., Luiz P. Kowalski, M.D., Ph.D., Maria E. Leon, Ph.D., Olena Mandrik, Ph.D., Toru Nagao, D.D.S., Ph.D., D.M.Sc., Vinayak M. Prasad, M.B., B.S., Ph.D., Kunnambath Ramadas, M.D., Ph.D., Felipe Roitberg, M.D., Pierre Saintigny, M.D., Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan, M.D., Alan R. Santos-Silva, D.D.S., Ph.D., Dhirendra N. Sinha, Ph.D., Patravoot Vatanasapt, M.D., Rosnah B. Zain, M.D.C., and Béatrice Lauby-Secretan, Ph.D.

October 18, 2022

Executive Summary by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

health transformation — institute for research, strategy and advisory

October 26, 2022

Overview

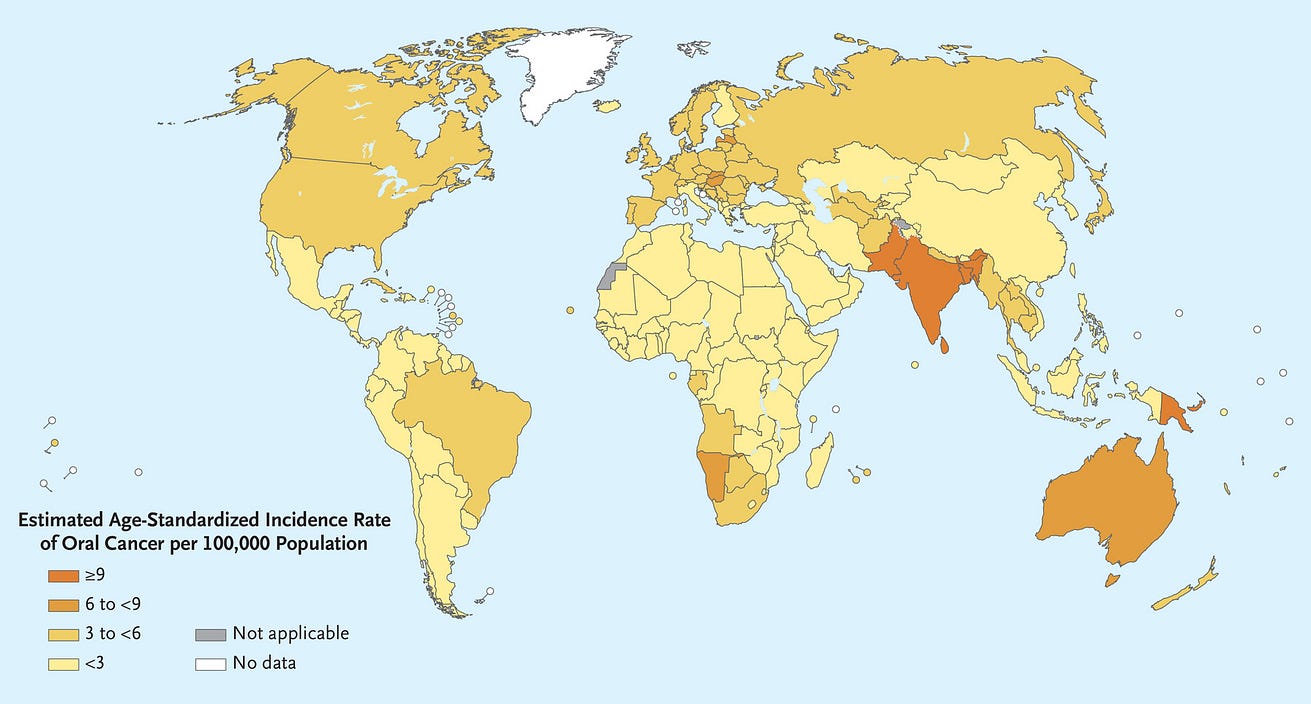

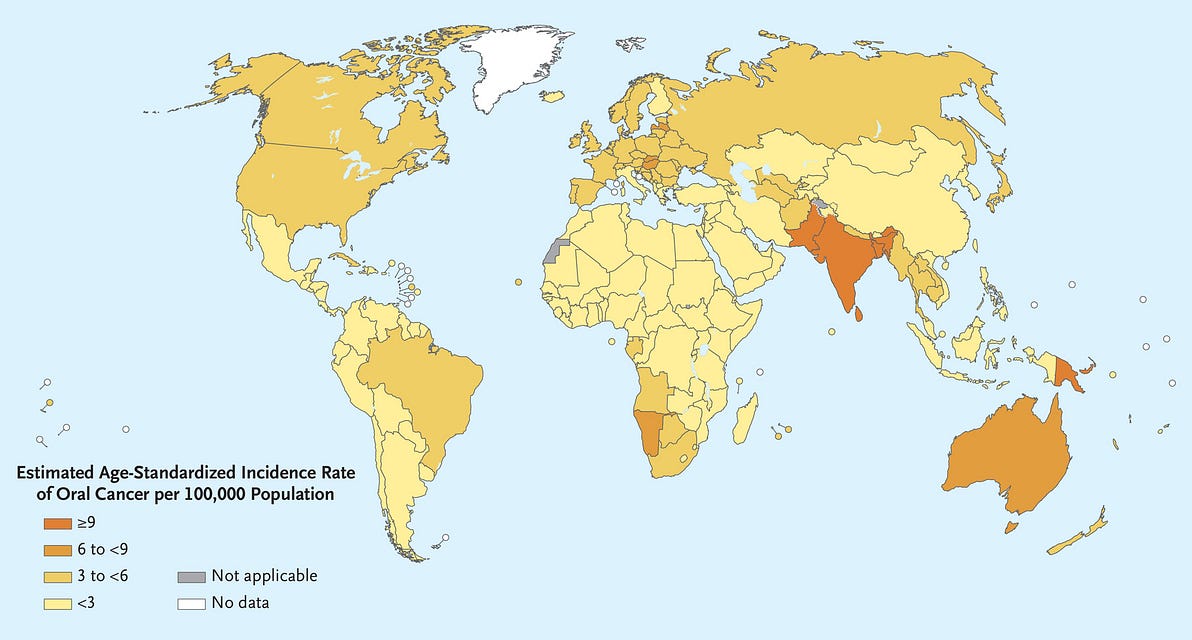

- In 2020, cancer of the lip and oral cavity was estimated to rank 16th in incidence and mortality worldwide and was a common cause of cancer death in men across much of South and Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific 1 (Figure 1).

[Figure 1 — Estimated Age-Standardized Incidence of Lip and Oral Cavity Cancers (2020).]

- A wide range of genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors contribute to the risk of oral cancer.2 Risks are dominated by tobacco, both smoked and smokeless, and heavy alcohol consumption.

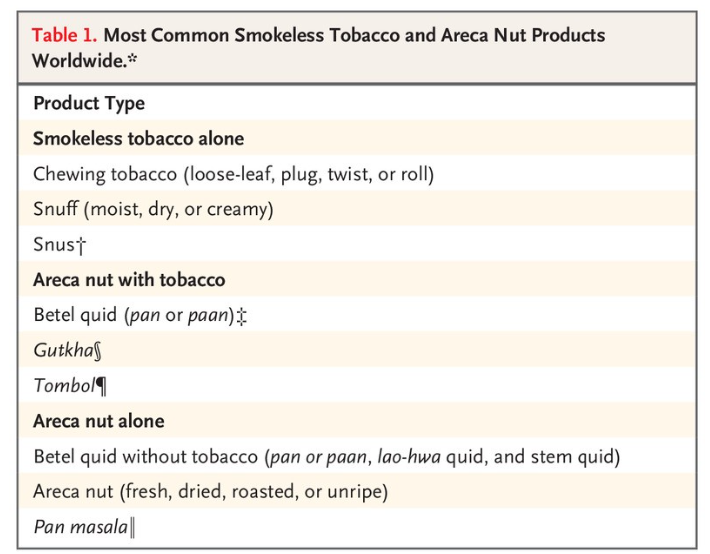

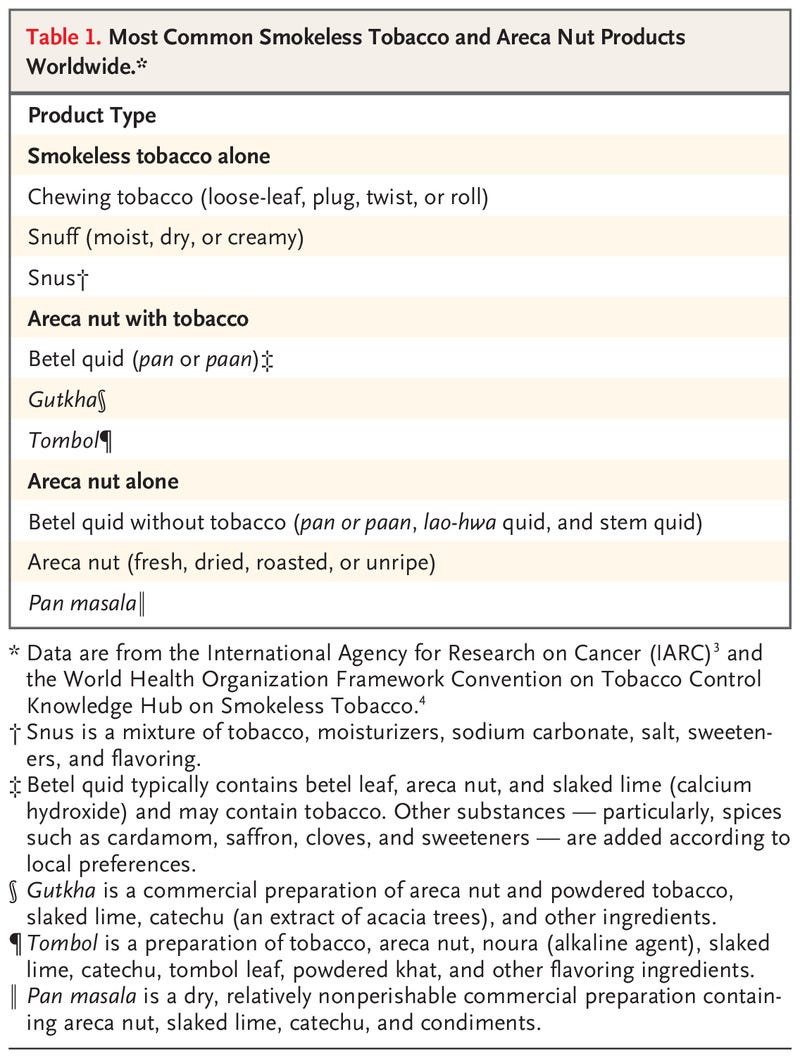

- In Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific Islands, where the incidence of oral cancer is high, the major risk factors are use of smokeless tobacco and areca nut products (including betel quid)3 (Table 1).4

- A small percentage of oral cancer worldwide (approximately 2%) is caused by human papillomavirus infection, primarily HPV16.5

- From September through December 2021, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) convened a working group of 25 scientists (all of whom are coauthors of this article) from 14 countries to evaluate the body of evidence on primary and secondary prevention of oral cancer.

- The working group reviewed all relevant published studies and evaluated the evidence according to the updated preambles of the IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention.6–8

- The preambles describe the objectives and scope of the program, general principles and procedures, and scientific review and evaluations.

- In addition, to strengthen the current published evidence with respect to areca nut products, the working group performed primary analyses of unpublished data from large studies.

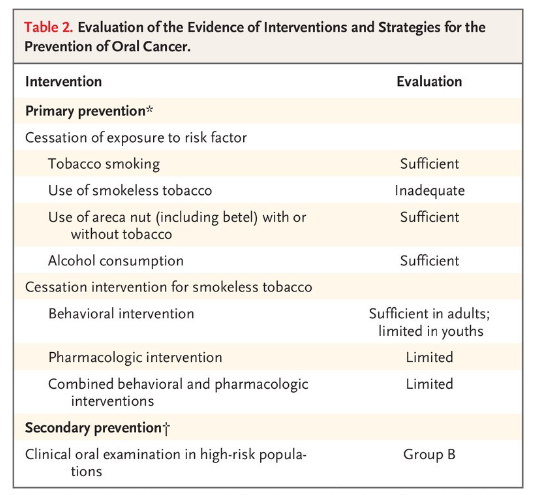

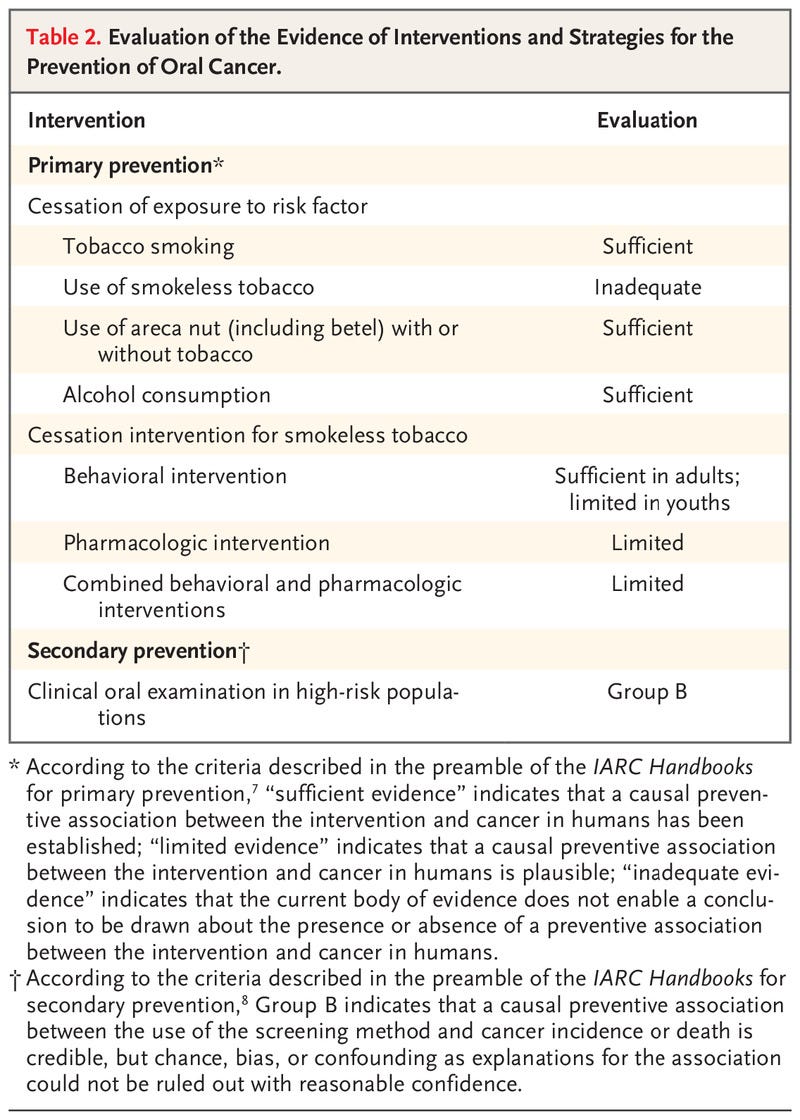

- Presented here is a brief overview of the studies that were reviewed and the outcomes of the evaluation process (Table 2)

For other sections:

See the original publication

Discussion and Conclusions

In this first evaluation of oral cancer prevention by the IARC Handbooks program, the working group found that tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption are the main drivers of oral cancer in most countries.

- However, the use of smokeless tobacco and chewing of areca nut products are the leading causes in many countries, especially in South and Southeast Asia and in the Western Pacific Islands.

- In these areas, the use of products (which may contain smokeless tobacco only, areca nut only, or both) vary widely in their nature and toxicity profile.

- In the available studies, a lack of detail regarding the composition of these products posed a challenge for the interpretation and evaluation of the current evidence.

Cessation of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption has a preventive effect on the incidence of oral cancer and probably also decreases the risk of oral potentially malignant disorders. In addition, smoking cessation has many other health benefits.

- Given that the combined effect of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption is greater than multiplicative, smoking cessation reduces the risk of oral cancer in persons who continue drinking alcohol.

- Similarly, the benefits of cessation in the use of areca nut products with or without tobacco have been established.

In reaching these conclusions, the working group considered that products vary substantially in composition, both within and among countries, and elected to evaluate jointly all products containing areca nut.

- Given interaction effects, large risk reductions would also be expected after smoking cessation in users of these products.

- Evidence for the benefits of cessation in the use of smokeless tobacco alone was inadequate because of the lack of studies in relevant geographic areas.

The effect of primary interventions for cessation of use of these products is specific to the country, culture, age, and sex of the target population.

- Very few studies were available in populations that commonly use areca nut with tobacco; therefore, the evaluations were limited to cessation of smokeless tobacco alone.

- As compared with adults, youth who initiate the use of smokeless tobacco often do not perceive tobacco as harmful and have high receptivity to tobacco advertising.

- Thus, it is important that education about harms of using these products focus on youths.

Clinical oral examination enables detection of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders relatively early in their evolution.

- Currently, no better screening alternative exists, although research into biomarkers in saliva, blood, and breath is burgeoning.

- The highly variable natural history of oral potentially malignant disorders at the individual level poses a challenge in extrapolating data to important end points such as mortality.

- Evidence is still lacking with respect to whether adjunctive optical techniques or biomarkers can reduce false positive screening results.51

Our evaluation of the potential for clinical oral examination to reduce oral cancer mortality applies to high-risk persons only.

- Its effect in the general population cannot be established on the basis of current evidence.47

- Screening performed by trained primary health care workers in low-resource settings has shown good results on early disease detection.

- Opportunistic screening in dental practices in locations where health care resources are high may also be effective, although the evidence is scarce.52

- The use of risk-based models for screening could be an appropriate approach for communities with a high incidence of oral cancer, with the acknowledgment that selection of participants is challenging from a programmatic perspective.

Screening performed by trained primary health care workers in low-resource settings has shown good results on early disease detection.

Opportunistic screening in dental practices in locations where health care resources are high may also be effective, although the evidence is scarce.52

The use of risk-based models for screening could be an appropriate approach for communities with a high incidence of oral cancer, with the acknowledgment that selection of participants is challenging from a programmatic perspective.

This review highlighted the paucity of data in the area of oral cancer prevention and calls for additional research in all aspects of such preventive work.

- Nonetheless, the working group established that cessation of tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and areca nut use will contribute to significant reductions in the risk of oral cancer.

- Such measures will also contribute to the overall objective of the resolution on oral health adopted by the World Health Assembly in May 2021 to control and prevent oral diseases, including oral cancer, by 2030.53

This review highlighted the paucity of data in the area of oral cancer prevention and calls for additional research in all aspects of such preventive work.

Nonetheless, the working group established that cessation of tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and areca nut use will contribute to significant reductions in the risk of oral cancer.

Authors Affiliations

From the International Agency for Research on Cancer (V.B., S.T.N., D.S., R.S., B.L.-S.), and INSERM 1052, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique 5286, Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Lyon, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, and the Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Léon Bérard (P.S.) — all in Lyon, France; the Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer of the World Health Organization (WHO) (S.W.) and the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral, and Craniofacial Sciences (N.W.J.), King’s College London, London, the University of Sheffield School of Health and Related Research, Sheffield (O.M.), and the School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Nursing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow (D.I.C.) — all in the United Kingdom; Center for Health, Innovation, and Policy Foundation and Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta (R.M.); the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (A.K.C.); the Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei (T.H.-H.C.); Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Ga-Rankuwa, and the School of Health Systems and Public Health, University of Pretoria, Pretoria — both in South Africa (O.A.A.-Y.); Healis Sekhsaria Institute for Public Health (P.C.G.) and Preventive Oncology, Karkinos Healthcare (R.S.), Navi Mumbai, Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, Thiruvananthapuram (D.A.), Regional Cancer Centre, Trivandrum (K.R.), and the School of Preventive Oncology, Patna (D.N.S.) — all in India; New York University College of Dentistry, New York (A.R.K.); University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka (W.M.T.); the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur (W.M.T., R.B.Z.), and MAHSA (Malaysian Allied Health Sciences Academy) University, Bandar Saujana Putra (R.B.Z.) — both in Malaysia; M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston (A.G.); Griffith University Gold Coast, Southport, QLD, Australia (N.W.J.); University of São Paulo Medical School and A.C. Camargo Cancer Center (L.P.K.), São Paulo, and Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas, Campinas (A.R.S.-S.) — all in Brazil;

the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, Aichi Gakuin University, Nisshin, Japan (T.N.); WHO, Geneva (V.M.P., F.R.); and the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand (P.V.).

Dr. Lauby-Secretan can be contacted at secretanb@iarc.who.int or at the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Evidence Synthesis and Classification Branch, 150 Albert Thomas, 69372 Lyon Cedex 8, France.

References

See the original publication

Originally published at https://www.nejm.org.

About the authors & affiliations

- Véronique Bouvard, Ph.D.,

- Suzanne T. Nethan, M.D.S.,

- Deependra Singh, Ph.D.,

- Saman Warnakulasuriya, Ph.D.,

- Ravi Mehrotra, M.D., Ph.D.,

- Anil K. Chaturvedi, M.P.H., Ph.D.,

- Tony Hsiu-Hsi Chen, Ph.D.,

- Olalekan A. Ayo-Yusuf, M.P.H., Ph.D.,

- Prakash C. Gupta, Ph.D.,

- Alexander R. Kerr, D.D.S.,

- Wanninayake M. Tilakaratne, Ph.D.,

- Devasena Anantharaman, Ph.D.,

- David I. Conway, D.P.H., Ph.D.,

- Ann Gillenwater, M.D.,

- Newell W. Johnson, F.Med.Sci.,

- Luiz P. Kowalski, M.D., Ph.D.,

- Maria E. Leon, Ph.D.,

- Olena Mandrik, Ph.D.,

- Toru Nagao, D.D.S., Ph.D., D.M.Sc.,

- Vinayak M. Prasad, M.B., B.S., Ph.D.,

- Kunnambath Ramadas, M.D., Ph.D.,

- Felipe Roitberg, M.D.,

- Pierre Saintigny, M.D.,

- Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan, M.D.,

- Alan R. Santos-Silva, D.D.S., Ph.D.,

- Dhirendra N. Sinha, Ph.D.,

- Patravoot Vatanasapt, M.D.,

- Rosnah B. Zain, M.D.C.,

- and Béatrice Lauby-Secretan, Ph.D.

About the Brazilian authors:

Felipe Roitberg, M.D.

Alan R. Santos-Silva, D.D.S., Ph.D.,

University of São Paulo Medical School and

A.C. Camargo Cancer Center (L.P.K.), São Paulo, and

Piracicaba Dental School,

University of Campinas, Campinas (A.R.S.-S.) — all in Brazil;

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

IARC Perspective on Oral Cancer Prevention

NEJM

Véronique Bouvard, Ph.D., Suzanne T. Nethan, M.D.S., Deependra Singh, Ph.D., Saman Warnakulasuriya, Ph.D., Ravi Mehrotra, M.D., Ph.D., Anil K. Chaturvedi, M.P.H., Ph.D., Tony Hsiu-Hsi Chen, Ph.D., Olalekan A. Ayo-Yusuf, M.P.H., Ph.D., Prakash C. Gupta, Ph.D., Alexander R. Kerr, D.D.S., Wanninayake M. Tilakaratne, Ph.D., Devasena Anantharaman, Ph.D., David I. Conway, D.P.H., Ph.D., Ann Gillenwater, M.D., Newell W. Johnson, F.Med.Sci., Luiz P. Kowalski, M.D., Ph.D., Maria E. Leon, Ph.D., Olena Mandrik, Ph.D., Toru Nagao, D.D.S., Ph.D., D.M.Sc., Vinayak M. Prasad, M.B., B.S., Ph.D., Kunnambath Ramadas, M.D., Ph.D., Felipe Roitberg, M.D., Pierre Saintigny, M.D., Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan, M.D., Alan R. Santos-Silva, D.D.S., Ph.D., Dhirendra N. Sinha, Ph.D., Patravoot Vatanasapt, M.D., Rosnah B. Zain, M.D.C., and Béatrice Lauby-Secretan, Ph.D.

October 18, 2022

Overview:

In 2020, cancer of the lip and oral cavity was estimated to rank 16th in incidence and mortality worldwide and was a common cause of cancer death in men across much of South and Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific 1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 — Estimated Age-Standardized Incidence of Lip and Oral Cavity Cancers (2020).

A wide range of genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors contribute to the risk of oral cancer.2 Risks are dominated by tobacco, both smoked and smokeless, and heavy alcohol consumption. In Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific Islands, where the incidence of oral cancer is high, the major risk factors are use of smokeless tobacco and areca nut products (including betel quid)3 (Table 1).4 A small percentage of oral cancer worldwide (approximately 2%) is caused by human papillomavirus infection, primarily HPV16.5

From September through December 2021, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) convened a working group of 25 scientists (all of whom are coauthors of this article) from 14 countries to evaluate the body of evidence on primary and secondary prevention of oral cancer. The working group reviewed all relevant published studies and evaluated the evidence according to the updated preambles of the IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention.6–8 The preambles describe the objectives and scope of the program, general principles and procedures, and scientific review and evaluations. In addition, to strengthen the current published evidence with respect to areca nut products, the working group performed primary analyses of unpublished data from large studies. Presented here is a brief overview of the studies that were reviewed and the outcomes of the evaluation process (Table 2)

Primary Prevention: Cessation of Exposure to Risk Factors

- 1.TOBACCO SMOKING

- 2.SMOKELESS TOBACCO USE

- 3.CHEWING ARECA NUT PRODUCTS WITH OR WITHOUT TOBACCO

- 4.ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

1.TOBACCO SMOKING

In 2007, the IARC concluded that “the risk of oral cancer is lower in former smokers than in current smokers” and that “the reduction in the risk…increases with increasing duration of abstinence.”9 The results of several additional studies on smoking cessation and oral cancer risk have since been published and reinforce this conclusion. These include two cohort studies,10,11 two case–control studies,12,13 and one meta-analysis of 17 case–control studies,14 all of which consistently showed a progressive reduction of oral cancer risk with an increasing duration of abstinence, findings that were significant in three studies. In the meta-analysis, reductions in the incidence of oral cancer among former smokers as compared with current smokers were detected within 4 years after cessation (35% reduction); risks approached those in never-smokers after 20 years or more of cessation (odds ratio, 0.19; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15 to 0.24).14

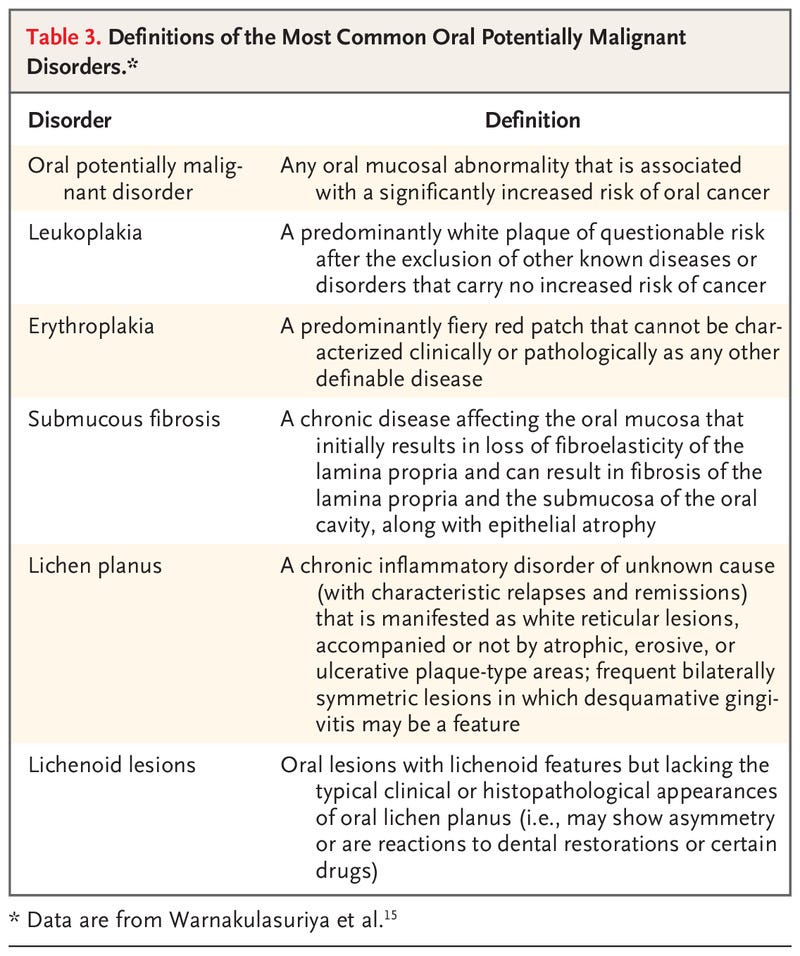

Table 3.

Studies have also suggested that the risk of oral potentially malignant disorders, particularly leukoplakia, decreases after smoking cessation (Table 3).15 In a large cohort study, the incidence of leukoplakia decreased by 85% after cessation of smoking of bidis (thin, hand-rolled cigarettes).16 In another large study in India, former smokers had a lower risk of leukoplakia than current smokers (relative risk, 1.7% vs. 3.4%).17 There was sufficient evidence that quitting tobacco smoking decreases the risk of oral cancer and that the risk decreases with increasing time since smoking cessation.

2.SMOKELESS TOBACCO USE

The working group found no studies that reported the risk of oral cancer according to the time since the cessation of smokeless tobacco use. Six studies examined oral cancer risk in current and former users as compared with never-users: two large cohort studies in Sweden18 and Norway19 and four case–control studies, three in Sweden20–22 and one in Yemen.23 These studies had major limitations and minimal geographic diversity, with no studies from South Asia. Eight studies examined associations between current and former use of smokeless tobacco and the risk of oral potentially malignant disorders, with never-users as the reference group. Although the findings were inconsistent, a meta-analysis conducted by the working group showed that former users of smokeless tobacco had a lower pooled risk of oral potentially malignant disorders (particularly leukoplakia) than current users. However, there was inadequate evidence that cessation of smokeless tobacco decreases the risk of oral cancer.

3.CHEWING ARECA NUT PRODUCTS WITH OR WITHOUT TOBACCO

The working group based its evaluations of areca nut products on data from published studies and from primary analyses, in which they used evidence regarding the time since cessation and supportive evidence regarding the age at the time of cessation for former users. Particular attention was given to adjustment for confounders and to precision of risk estimates.

One case–control study24 combined with primary data analyses of three large cohort studies and one case–control study (all conducted in Taiwan) showed that the risk of oral cancer decreased significantly with increasing time since cessation of the use of areca nut products without tobacco. Risk reductions were 2.3 to 6.7% per year after cessation and 17 to 51% for long-term cessation (≥10 years). For cessation of the use of products containing areca nut with tobacco, published studies had inconsistent results. However, primary analyses from one cohort study and a case–control study, both of which were performed in India, showed a reduction in the risk of oral cancer with increasing time after cessation of 2 to 3% (95% CI, 1 to 5) per year of cessation. A recently published meta-analysis confirmed risk reversal for oral cancer with long-term cessation.25

The working group also evaluated the effect of cessation on the risk of oral potentially malignant disorders on the basis of the above-mentioned studies. Risk reductions were observed with increasing time since cessation of chewing products containing areca nut without tobacco. A primary intervention study showed strong reductions in the incidence of leukoplakia 5 years after the intervention for cessation of chewing areca nut with tobacco: 49% (95% CI, 7 to 72) in men and 81% (95% CI, 70 to 89) in women.26

There was sufficient evidence that the cessation of use of areca nut products with or without tobacco decreases the risk of oral cancer. Cessation of the use of areca nut products with or without tobacco also decreases the risk of oral potentially malignant disorders.

4.ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

Published evidence that the cessation of alcohol consumption was associated with a reduction in the risk of oral cancer consisted of two cohort studies involving current and former drinkers as compared with never-drinkers and one meta-analysis of 13 case–control studies and three additional case–control studies that showed risk estimates according to the time since cessation. In the international meta-analysis,14 the risk of oral cancer decreased significantly with increasing time since cessation, with an odds ratio of 0.43 (95% CI, 0.28 to 0.67) for former heavy drinkers (≥3 drinks per day) after more than 20 years since cessation as compared with current drinkers. The working group did not identify any studies that evaluated the time since alcohol cessation with respect to the risk of oral potentially malignant disorders. In seven case–control studies, the risk of oral potentially malignant disorders (particularly leukoplakia and erythroplakia) was generally lower among former drinkers than among current drinkers.17,27 There was sufficient evidence that quitting alcohol consumption decreases the risk of oral cancer and that the risk decreases with increasing time since quitting.

Primary Prevention: Cessation Interventions

Interventions for cessation of smokeless tobacco or areca nut use include behavioral interventions, pharmacologic interventions, and a combination of both. Of the 33 studies that were reviewed, 70% had been performed in the United States; five had been done in India, two in Sweden, and one each in Norway and Taiwan.

Nine studies — seven randomized clinical trials and two cohort studies28,29 — assessed behavioral interventions for cessation in adults. Only one study, which was performed in India, involved users of areca nut with tobacco28; all the other studies involved populations using smokeless tobacco alone. One or more of various types of interventions were provided. All the studies showed a positive effect of cessation, which was significant in six studies,28–33 with estimates of relative risk in the control group as compared with the intervention group ranging from 1.28 at 6 months of follow-up to 25.70 at 60 months. It is worth noting that in two of those studies,29,32 the control group also received some form of intervention. There was sufficient evidence that behavioral interventions in adults are effective in inducing cessation in the use of smokeless tobacco.

Five studies — four randomized clinical trials and one cohort study — assessed behavioral interventions for cessation in youth. Only one study, which was performed in the United States, showed a significant effect on cessation at 12 months of follow-up, with a relative risk of 1.70 (95% CI, 1.50 to 1.86) in the control group as compared with the intervention group.34 Another U.S. study showed a significant positive effect of the intervention in preventing the initiation of using smokeless tobacco (relative risk, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.99).35 There was limited evidence that behavioral interventions in youth are effective in inducing cessation in the use of smokeless tobacco.

In three randomized clinical trials, investigators assessed the effectiveness of nicotine gum in cessation in the use of smokeless tobacco and betel quid without tobacco in India,36 the effectiveness of nicotine lozenges in cessation in the use of smokeless tobacco in the United States,37 and the effectiveness of antidepressants in the cessation of areca nut use in Taiwan.38 Some positive associations were seen, but the studies were of limited informativeness. There was limited evidence that pharmacologic interventions with nicotine replacement therapy or antidepressants are effective in inducing cessation in the use of smokeless tobacco or areca nut products.

Of 16 randomized clinical trials assessing combined pharmacologic and behavioral interventions, only one study assessed the use of areca nut products with tobacco; all the others evaluated smokeless tobacco cessation. Although positive effects of the intervention on cessation rates were observed in 13 of 16 studies, the difference with control was significant in only two studies involving smokeless tobacco users, one in the United States37 and one in Sweden.39 There was limited evidence that combined pharmacologic and behavioral interventions were effective in inducing cessation of smokeless tobacco use.

Primary Prevention Policies

The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) of the World Health Organization (WHO) was established in 2005 with a set of demand-and-supply reduction measures.40 However, the actions that have been taken have been variable, and few outcome data are available about smokeless tobacco use. In one U.S. study, investigators found that tobacco taxation had reduced the prevalence of smokeless tobacco use in youth.41 One study in Bangladesh42 and three in India43–45 estimated that higher prices would reduce the use of smokeless tobacco. Combinations of evidence-based FCTC policies appear to be more effective.

Policies to control the use of areca nut are still relatively new, and the working group could find no published data on their effects. Such policies have been implemented in areas — including Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Guangzhou (China), and Taiwan — that have a high prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis and of oral cancer. The most common policy, which was implemented in five countries, is a ban on spitting in public places. Authorities are urged to enhance surveillance of smokeless tobacco and areca use across the globe and to promote cessation policies for these products.

Secondary Prevention: Screening for Oral Cancer

Clinical oral examination is the only screening method that is routinely used for the detection of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders. Clinical oral examination consists of a white-light visual examination and palpation of the oral cavity mucosa and the external facial and neck regions. The sensitivity of clinical oral examination for the detection of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders ranges from 50 to 99%, with a specificity of 75 to 99%.46 The importance of the role of well-trained health care workers in the performance of clinical oral examinations was noted.

In a randomized clinical trial that was conducted in India with 15 years of follow-up, investigators found that clinical oral examination was associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of advanced oral cancer (by 21%; 95% CI, 5 to 35) and in the risk of death from oral cancer (by 24%; 95% CI, 3 to 40) among high-risk persons (i.e., users of tobacco, alcohol, areca nut products, or all three).47 Two cohort studies that involved the same screened cohort in Taiwan and one case–control study in Cuba48–50 showed that clinical oral examination was associated with reductions of 21 to 22% in the incidence of advanced oral cancer and reductions of 24 to 26% in the risk of death; the differences were significant in the cohort studies.49,50 However, these studies had several limitations, including low compliance of screening-positive cases with further assessment,47 selection bias for those screened, possible contamination of controls,49,50 lack of statistical power, and low coverage of the program.48 Studies did not indicate whether any primary prevention interventions were being conducted in the population47–50 or provide data on the proportion of high-risk members in the control group.48 The working group concluded that screening of high-risk persons by clinical oral examination may reduce mortality from oral cancer.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this first evaluation of oral cancer prevention by the IARC Handbooks program, the working group found that tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption are the main drivers of oral cancer in most countries. However, the use of smokeless tobacco and chewing of areca nut products are the leading causes in many countries, especially in South and Southeast Asia and in the Western Pacific Islands. In these areas, the use of products (which may contain smokeless tobacco only, areca nut only, or both) vary widely in their nature and toxicity profile. In the available studies, a lack of detail regarding the composition of these products posed a challenge for the interpretation and evaluation of the current evidence.

Cessation of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption has a preventive effect on the incidence of oral cancer and probably also decreases the risk of oral potentially malignant disorders. In addition, smoking cessation has many other health benefits. Given that the combined effect of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption is greater than multiplicative, smoking cessation reduces the risk of oral cancer in persons who continue drinking alcohol.

Similarly, the benefits of cessation in the use of areca nut products with or without tobacco have been established. In reaching these conclusions, the working group considered that products vary substantially in composition, both within and among countries, and elected to evaluate jointly all products containing areca nut. Given interaction effects, large risk reductions would also be expected after smoking cessation in users of these products. Evidence for the benefits of cessation in the use of smokeless tobacco alone was inadequate because of the lack of studies in relevant geographic areas.

The effect of primary interventions for cessation of use of these products is specific to the country, culture, age, and sex of the target population. Very few studies were available in populations that commonly use areca nut with tobacco; therefore, the evaluations were limited to cessation of smokeless tobacco alone. As compared with adults, youth who initiate the use of smokeless tobacco often do not perceive tobacco as harmful and have high receptivity to tobacco advertising. Thus, it is important that education about harms of using these products focus on youths.

Clinical oral examination enables detection of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders relatively early in their evolution. Currently, no better screening alternative exists, although research into biomarkers in saliva, blood, and breath is burgeoning. The highly variable natural history of oral potentially malignant disorders at the individual level poses a challenge in extrapolating data to important end points such as mortality. Evidence is still lacking with respect to whether adjunctive optical techniques or biomarkers can reduce false positive screening results.51

Our evaluation of the potential for clinical oral examination to reduce oral cancer mortality applies to high-risk persons only. Its effect in the general population cannot be established on the basis of current evidence.47 Screening performed by trained primary health care workers in low-resource settings has shown good results on early disease detection. Opportunistic screening in dental practices in locations where health care resources are high may also be effective, although the evidence is scarce.52 The use of risk-based models for screening could be an appropriate approach for communities with a high incidence of oral cancer, with the acknowledgment that selection of participants is challenging from a programmatic perspective.

This review highlighted the paucity of data in the area of oral cancer prevention and calls for additional research in all aspects of such preventive work. Nonetheless, the working group established that cessation of tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and areca nut use will contribute to significant reductions in the risk of oral cancer. Such measures will also contribute to the overall objective of the resolution on oral health adopted by the World Health Assembly in May 2021 to control and prevent oral diseases, including oral cancer, by 2030.53

This article was published on October 18, 2022, at NEJM.org.

Authors Affiliations

From the International Agency for Research on Cancer (V.B., S.T.N., D.S., R.S., B.L.-S.), and INSERM 1052, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique 5286, Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Lyon, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, and the Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Léon Bérard (P.S.) — all in Lyon, France; the Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer of the World Health Organization (WHO) (S.W.) and the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral, and Craniofacial Sciences (N.W.J.), King’s College London, London, the University of Sheffield School of Health and Related Research, Sheffield (O.M.), and the School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Nursing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow (D.I.C.) — all in the United Kingdom; Center for Health, Innovation, and Policy Foundation and Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta (R.M.); the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (A.K.C.); the Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei (T.H.-H.C.); Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Ga-Rankuwa, and the School of Health Systems and Public Health, University of Pretoria, Pretoria — both in South Africa (O.A.A.-Y.); Healis Sekhsaria Institute for Public Health (P.C.G.) and Preventive Oncology, Karkinos Healthcare (R.S.), Navi Mumbai, Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, Thiruvananthapuram (D.A.), Regional Cancer Centre, Trivandrum (K.R.), and the School of Preventive Oncology, Patna (D.N.S.) — all in India; New York University College of Dentistry, New York (A.R.K.); University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka (W.M.T.); the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur (W.M.T., R.B.Z.), and MAHSA (Malaysian Allied Health Sciences Academy) University, Bandar Saujana Putra (R.B.Z.) — both in Malaysia; M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston (A.G.); Griffith University Gold Coast, Southport, QLD, Australia (N.W.J.); University of São Paulo Medical School and A.C. Camargo Cancer Center (L.P.K.), São Paulo, and Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas, Campinas (A.R.S.-S.) — all in Brazil;

the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, Aichi Gakuin University, Nisshin, Japan (T.N.); WHO, Geneva (V.M.P., F.R.); and the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand (P.V.).

Dr. Lauby-Secretan can be contacted at secretanb@iarc.who.int or at the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Evidence Synthesis and Classification Branch, 150 Albert Thomas, 69372 Lyon Cedex 8, France.

References

See the original publication

Originally published at https://www.nejm.org.

About the authors & affiliations

- Véronique Bouvard, Ph.D.,

- Suzanne T. Nethan, M.D.S.,

- Deependra Singh, Ph.D.,

- Saman Warnakulasuriya, Ph.D.,

- Ravi Mehrotra, M.D., Ph.D.,

- Anil K. Chaturvedi, M.P.H., Ph.D.,

- Tony Hsiu-Hsi Chen, Ph.D.,

- Olalekan A. Ayo-Yusuf, M.P.H., Ph.D.,

- Prakash C. Gupta, Ph.D.,

- Alexander R. Kerr, D.D.S.,

- Wanninayake M. Tilakaratne, Ph.D.,

- Devasena Anantharaman, Ph.D.,

- David I. Conway, D.P.H., Ph.D.,

- Ann Gillenwater, M.D.,

- Newell W. Johnson, F.Med.Sci.,

- Luiz P. Kowalski, M.D., Ph.D.,

- Maria E. Leon, Ph.D.,

- Olena Mandrik, Ph.D.,

- Toru Nagao, D.D.S., Ph.D., D.M.Sc.,

- Vinayak M. Prasad, M.B., B.S., Ph.D.,

- Kunnambath Ramadas, M.D., Ph.D.,

- Felipe Roitberg, M.D.,

- Pierre Saintigny, M.D.,

- Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan, M.D.,

- Alan R. Santos-Silva, D.D.S., Ph.D.,

- Dhirendra N. Sinha, Ph.D.,

- Patravoot Vatanasapt, M.D.,

- Rosnah B. Zain, M.D.C.,

- and Béatrice Lauby-Secretan, Ph.D.

About the Brazilian authors:

Felipe Roitberg, M.D.

Alan R. Santos-Silva, D.D.S., Ph.D.,

University of São Paulo Medical School and

A.C. Camargo Cancer Center (L.P.K.), São Paulo, and

Piracicaba Dental School,

University of Campinas, Campinas (A.R.S.-S.) — all in Brazil;