The Health Transformation — strategy institute

Joaquim Cardoso MSc*

Chief Strategy Officer (CSO), Researcher and Editor

November 19, 2022

MSc* from London Business School — MIT Sloan Masters Program

Key Facts

- In the United States, 54% of nurses and physicians, 60% of medical students and residents, and 61% of pharmacists have symptoms of burnout.

- Burnout is a long-standing issue and a fundamental barrier to professional well-being.

- It was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience today released for public input through May 27 a draft National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being, which builds on almost six years of work among 200 participants, including the AHA.

What is the business case

- Before the pandemic, societal costs attributable to health worker burnout in the United States were estimated at $4.6 billion (NASEM, 2019).

- The costs will only grow, as recent surveys showed high-stress work environments are driving more physicians (20 percent) and nurses (40 percent) to leave practice after two years of the pandemic (Abbasi, 2022).

- In addition, more than 25 percent of employees in state and local public health departments indicated they are considering leaving their organizations,

- which exacerbates an already dire situation, as the public health workforce has lost 20 percent of workers since 2008

AHA News

May 20, 2022

The National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience today released for public input through May 27 a draft National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being, which builds on almost six years of work among 200 participants, including the AHA.

The plan identifies goals and actions to help health care leaders, educators, governing boards and federal agencies achieve health workforce well-being across seven priority areas:

positive work and learning environments and culture; measurement, assessment, strategies and research of well-being; mental health and stigma; compliance, regulatory and policy barriers for health workers’ daily work; effective technology tools; effects of COVID-19 on the health workforce; and recruitment of the next generation.

AHA President and CEO Rick Pollack and AHA Chief Nursing Officer Robyn Begley, CEO of the American Organization for Nursing Leadership, said, “When others ran from the pandemic, health care workers ran toward it to try to prevent the spread, care for the sick and save lives.

The health care workforce has worked tirelessly to provide lifesaving care for patients but it has come with a heavy toll on their own well-being.

The AHA is proud to be a member of the National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience to develop solutions to help our workforce ensure they have the support, resources and wellness programs to keep them mentally and physically healthy.”

During a NAM webinar today on the plan, Pollack shared two key takeaways from the hospital and health system perspective: the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated health disparities, lack of access to behavioral health care, and health care worker shortages and resiliency to the level of a national emergency; and solutions require collaborative efforts across the entire health system and its stakeholders.

Originally published at https://www.aha.org.

Health workers who find joy, fulfillment, and meaning in their work can engage on a deeper level with their patients, who are at the heart of health care.

Thus, a thriving workforce is essential for delivering safe, high-quality, patient-centered care.

The National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being is intended to inspire collective action that focuses on changes needed across the health system and at the organizational level to improve the well-being of the health workforce.

As a nation, we must redesign how health is delivered so that human connection is strengthened, health equity is achieved, and trust is restored.

The National Plan’s vision is that patients are cared for by a health workforce that is thriving in an environment that fosters their well-being as they improve population health, enhance the care experience, reduce costs, and advance health equity; therefore, achieving the “quintuple aim.”

Together, we can create a health system in which care is delivered joyfully and with meaning, by a committed team of all who work to advance health, in partnership with engaged patients and communities.

Highlights

Taking Collective Action for the Future of the Nation’s Health System The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience in October 2022 launched the National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being, which intends to drive collective action to strengthen health workforce well-being and restore the health of the nation.

The vision is that people are cared for by a health workforce that is thriving in an environment that fosters their well-being as they improve population health, enhance the care experience, reduce costs, and advance health equity.

The National Plan identifies the following seven priority areas for health workforce well-being:

7 Priority Areas in the NAM National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being

1.Create and sustain positive work and learning environments and culture.

Transform health systems, and health education and training, by prioritizing and investing in efforts to optimize environments that prevent and reduce burnout, foster professional well-being, and support quality care.

2.Invest in measurement, assessment, strategies, and research.

Expand the uptake of existing tools at the health system level and advance national research on decreasing health worker burnout and improving well-being.

3.Support mental health and reduce stigma.

Provide support to health workers by eliminating barriers and reducing stigma associated with seeking services needed to address mental health challenges.

4.Address compliance, regulatory, and policy barriers for daily work.

Prevent and reduce the unnecessary burdens that stem from laws, regulations, policies, and standards placed on health workers.

5.Engage effective technology tools.

Optimize and expand the use of health information technologies that support health workers in providing high-quality patient care and serving population health, and minimize technologies that inhibit clinical decision-making or add to administrative burden.

6.Institutionalize well-being as a long-term value.

Ensure COVID-19 recovery efforts address the toll on health worker well-being now and in the future, and bolster the public health and health care systems for future emergencies.

7.Recruit and retain a diverse and inclusive health workforce.

Promote careers in the health professions and increase pathways and systems for a diverse, inclusive, and thriving workforce.

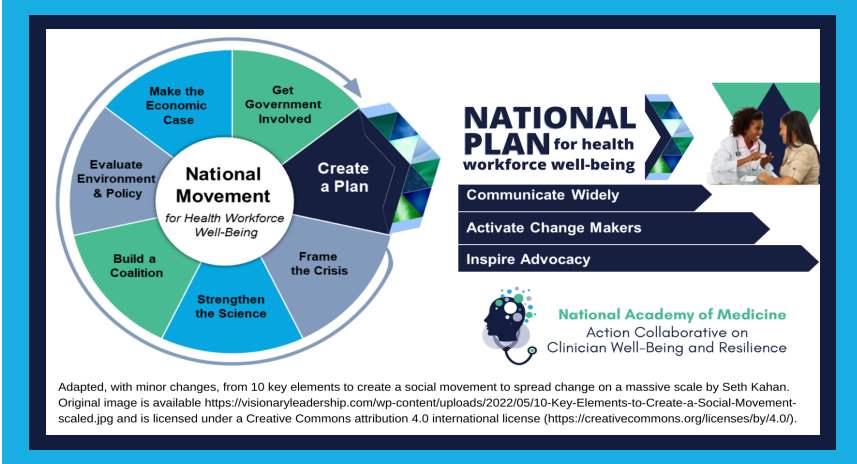

Building a National Movement for Health Workforce Well-Being

The National Plan is a crucial starting point for collective action that will help coordinate actions across the field and provide a roadmap to develop a health system in which health is delivered joyfully and with meaning, by a committed team, in partnership with engaged patients and communities.

Many of the foundational pieces are in place to continue a national movement to advance health workforce well-being through the NAM Clinician Well-Being Collaborative.

It will take the collective efforts of many individuals, organizations, and coalitions of actors to reverse trends in health worker burnout.

There are 10 key elements for driving a successful national movement, and the NAM Clinician Well-Being Collaborative has been working on several of these elements since 2017.

1.Frame the Crisis

In 2017, the NAM established the Clinician Well-Being Collaborative to raise the visibility of clinician anxiety, burnout, depression, and suicide, recognizing that clinician well-being is essential for safe, high-quality patient care. The Clinician Well-Being Collaborative’s work prior to and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic recognizes the challenges facing health workers as systemic, complex, and longstanding.

2. Strengthen the Science

The NAM published the report, Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being in 2019. The Clinician Well-Being Collaborative is also a leader in identifying evidence-based strategies to improve clinician well-being at both the individual and systems levels. Products include an online knowledge hub, a series of NAM Perspectives papers, and a conceptual model that reflects the domains affecting clinician well-being.

3.Build a Coalition

At the outset, the Clinician Well-Being Collaborative focused on fostering a community of diverse stakeholders across the health care system. More than 200 organizations have joined the Clinician Well-Being Collaborative’s network by making a visible commitment to tackle the issue of clinician burnout and support the work and priorities of the Clinician WellBeing Collaborative locally.

4.Evaluate Environment & Policy

Working groups of the Collaborative have identified evidence-based strategies to engage leadership, break the culture of silence, organize promising practices and metrics, address workload and workflow, and act on recommendations to improve clinician wellbeing. Recent focus areas include mobilizing national stakeholders, reviewing and applying lessons from COVID-19, and implementing evidence-based tools for clinician well-being.

5.Make the Economic Case

The NAM’s Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout report raised the far-reaching consequences of burnout at the personal, organizational, and societal level.

The report estimates $4.6 billion in societal costs each year in the U.S. due to the U.S. clinical workforce reporting substantial symptoms of burnout.

The Clinician Well-Being Collaborative launched a Resource Compendium for Health Care Worker Well-Being, featuring tools to calculate the organizational costs of burnout and other resources for health care leaders and workers to use across practice settings.

The report estimates $4.6 billion in societal costs each year in the U.S. due to the U.S. clinical workforce reporting substantial symptoms of burnout.

6.Get Government Involved

The Clinician Well-Being Collaborative has more than 100 members across sectors who participate in working groups, including representatives from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, and Veterans Health Administration. In 2021, the Office of the Surgeon General joined the Clinician Well-Being Collaborative, to lead alongside the NAM, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and the Association of American Medical Colleges.

7.Create a Plan

The priorities, goals, and actions laid out in the National Plan are urgent, yet complex. The NAM has created a National Plan to focus on the immediate and long-term needs of the health workforce with the intention that the goals and actions will enable a sustained state of well-being. Every actor and sector should identify the most pressing priorities or promising opportunities and develop plans for near-, medium-, and long-term actions in accordance with available resources and in collaboration with other actors.

Now, it is critical to organize major engagement efforts to:

8.Communicate the Details of the National Plan Widely

9.Activate Change Makers to Spark Action Across the Nation

10.Inspire Advocacy of the National Plan

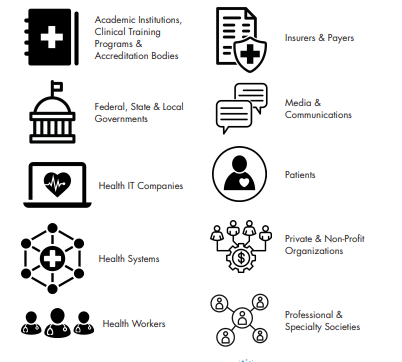

Actor Groups Needed for the National Movement

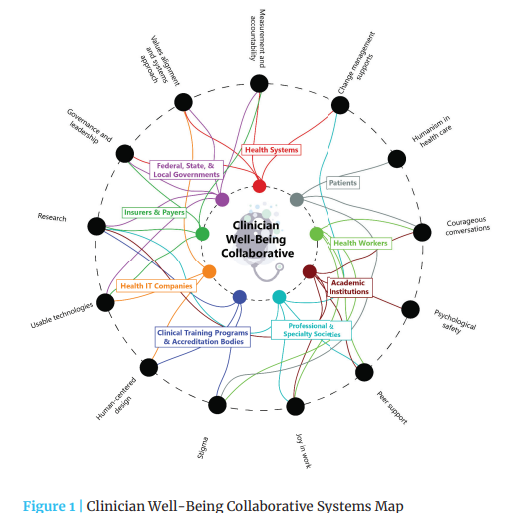

Improving health worker well-being is a shared responsibility that requires collective action by all actors in the U.S. health system and those who influence the systems that support health.

No single actor is responsible for making the significant investments needed to result in sustainable, system-wide changes and to achieve the vision set out in this National Plan.

The National Plan identifies the following actor groups:

Introduction

Health systems do not exist in isolation. Political, market, professional, and cultural forces heavily influence health care delivery, workplace stress, and health worker professional well-being.

For decades, health workers have been reporting a loss of meaning in work due to overwhelming job demands and limited supportive resources in the environments in which they operate (Maslach, 2018).

- In the United States, up to 54 percent of nurses and physicians, 60 percent of medical students and residents, and 61 to 75 percent of pharmacists have symptoms of burnout — high emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (e.g., cynicism), or a low sense of personal accomplishment from work (Jones et al., 2017; NASEM, 2019; Patel et al., 2021).

- Burnout is a longstanding issue and a fundamental barrier to professional well-being. It was further exacerbated by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

- Health workers who find joy, fulfillment, and meaning in their work can engage on a deeper level with their patients, who are at the heart of health care (Lai et al., 2022; NASEM, 2019).

- Thus, a thriving workforce is essential for delivering safe, high-quality, patient-centered care.

For decades, health workers have been reporting a loss of meaning in work due to overwhelming job demands and limited supportive resources in the environments in which they operate (Maslach, 2018).

While the challenge of sustaining the health workforce predated the pandemic, health care teams, including allied health professionals and health care support workers, as well as public health workers, experienced fear while responding to COVID-19 …

… — for their personal safety, contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to others, and feeling inadequately prepared to save lives as patients died from a previously unknown disease.

They experienced extreme mental and physical fatigue, isolation, and moral and traumatic distress and injury (NAM, 2022a).

In April 2020, the death of Dr. Lorna Breen, an emergency physician in New York City, captured national attention and galvanized political action; many members of the public could clearly see the toll on health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Knoll et al., 2020).

They experienced extreme mental and physical fatigue, isolation, and moral and traumatic distress and injury (NAM, 2022a).

The pandemic forced the nation to broaden its understanding of the external environment’s effects on health delivery and health worker well-being.

Early in the pandemic, the world witnessed how health worker physical and emotional well-being was aff ected by a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), long hours, and a lack of real-time data to inform clinical decision making.

Changing policies at the federal and state levels were critical to adjusting procedures at the organizational level to save lives, though inadequate communication sometimes led to confusion (AAOS, n.d.; Archambault, 2022).

Moreover, the public’s behaviors seemed to be driven by political ideologies that led to tensions over masks and physical distancing (Hardy et al., 2021).

According to multiple surveys of health workers, tensions related to COVID-19 escalated to bullying, harassment, threats, and violence against health workers at work and online (Larkin, 2021).

Trust and respect between the public and health workers eroded, ultimately threatening the health workforce’s contract with society — dedication to serving the interests of patients while maintaining the public’s trust and respect for health workers.

The pandemic forced the nation to broaden its understanding of the external environment’s effects on health delivery and health worker well-being.

The inequalities that were exacerbated by the pandemic extended to health care environments.

Black and Latino/a health workers reported the highest stress levels during the pandemic when compared to White workers (Berg, 2021).

This was fueled in part by a greater fear of exposure to COVID-19, since racial and ethnic minority groups disproportionately comprised “essential workers” and other frontline care positions, and were therefore at greater risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19.

Asian and Pacific Islander health workers also reported high stress levels fueled by the pandemic and anti-Asian hate expressed via slurs and physical assaults (Yi, 2020).

At a National Academy of Medicine (NAM) convening on unifying the health workforce in March 2022, experts further highlighted the unequal distribution of the burdens placed on certain groups of health workers (see Appendix B for more details on this convening).

While all health worker groups experienced challenges during the pandemic, the emotional well-being of health workers of color were disproportionately affected by COVID-19-related workplace bias, discrimination, and harassment from patients, superiors, and co-workers (NAM, 2022a).

One of the first studies to quantify the interplay of individual factors (such as race) with work environmental factors found that nurses of color were hit hard — they reported “higher emotional distress, more negative racial climates, more racial microaggressions, and higher levels of COVID worry” compared to White nurses (Thomas-Hawkins et al., 2022).

Women of color also occupy the majority of jobs, such as nursing assistants and home health aides, in the United States that faced direct occupational and safety risks from lack of protective measures and equipment (CAP, 2020; UNHR, 2020).

As schools, daycares, and elder-care facilities closed, female health workers were more often aff ected by additional caregiving responsibilities compared to their male counterparts (CAP, 2020; NAM, 2022b).

health workers also reported more work-home confl icts during the pandemic in addition to existing gender-based diff erences suggested in multiple studies (NAM, 2022b; Templeton et al., 2019).

The resulting severe health workforce shortage, beyond prepandemic projections and most critically among nurses, health aides, and assistants, places an enormous burden on remaining health workers and jeopardizes the health of the nation (AHA, 2021; Frogner and Dill, 2022).

Before the pandemic, societal costs attributable to health worker burnout in the United States were estimated at $4.6 billion (NASEM, 2019).

The costs will only grow, as recent surveys showed high-stress work environments are driving more physicians (20 percent) and nurses (40 percent) to leave practice after two years of the pandemic (Abbasi, 2022).

In addition, more than 25 percent of employees in state and local public health departments indicated they are considering leaving their organizations, which exacerbates an already dire situation, as the public health workforce has lost 20 percent of workers since 2008 (de Beaumont, 2021; Stone et al., 2021).

Before the pandemic, societal costs attributable to health worker burnout in the United States were estimated at $4.6 billion (NASEM, 2019).

TAKING COLLECTIVE ACTION FOR THE FUTURE OF THE NATION’S HEALTH SYSTEM

Collective action is urgently needed to prevent a dissolution of the health professions and to ensure a strong and interconnected health system for the nation.

Health workers have been operating in a survival state for a long time, but change is possible.

Therefore, an important step is a well-coordinated plan that provides the government, health systems leadership and governance, payers, industry, education, health workers, and leaders in other sectors with the tools and approaches required to drive policy and structural changes.1

As members of the NAM’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience2 have learned from numerous leading studies and reports, the solution is to take a systems approach that recognizes that no single variable in the health system is to blame for the problem of burnout.

… the solution is to take a systems approach that recognizes that no single variable in the health system is to blame for the problem of burnout.

Addressing the issue from multiple angles is necessary to redesign environments, so that patients are met with a thriving health workforce that approaches them with all of the skills, expertise, care, and attention they have at their disposal (NASEM, 2019).

Addressing the issue from multiple angles is necessary to redesign environments, so that patients are met with a thriving health workforce that approaches them with all of the skills, expertise, care, and attention they have at their disposal …

Leaders have tremendous responsibility and opportunity to address systems issues at the root of workplace stress and burnout.

Reducing burnout and moral distress are not enough to achieve professional well-being, though addressing the factors contributing to burnout is fundamental to fostering professional well-being and a thriving health workforce.

Reducing burnout and moral distress are not enough to achieve professional well-being, though addressing the factors contributing to burnout is fundamental to fostering professional well-being and a thriving health workforce.

This National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being (National Plan) is intended to inspire collective action that focuses on changes needed across the health system and at the organizational level to improve the well-being of the health workforce.

As a nation, we must redesign how health is delivered so that human connection is strengthened, health equity is achieved, and trust is restored.

Health delivery can be less transactional and instead center relationships.

Our nation should strengthen the public health system and re-invest in the public health infrastructure so that leaders and decision-makers are using the best data and evidence to guide policies locally and across the United States.

We need to make investments in the health system, not solely for a financial return on investment, but to improve health delivery and for the long-term well-being of our society.

Together, we can create a health system in which care is delivered joyfully and with meaning, by a committed team of all who work to advance health, in partnership with engaged patients and communities.

Together, we can create a health system in which care is delivered joyfully and with meaning, by a committed team of all who work to advance health, in partnership with engaged patients and communities.

The National Plan’s vision is that patients are cared for by a health workforce that is thriving in an environment that fosters their well-being as they improve population health, enhance the care experience, reduce costs, and advance health equity, therefore achieving the “quintuple aim.”

The National Plan’s vision is that patients are cared for by a health workforce that is thriving in an environment that fosters their well-being as they improve population health, enhance the care experience, reduce costs, and advance health equity, therefore achieving the “quintuple aim.”

PRIORITIES OF THE NATIONAL PLAN

The National Plan addresses seven priority areas, each focusing on the immediate and long-term needs of the health workforce with the intention that the goals and actions will enable a sustained state of well-being.

Each chapter is devoted to discussing a priority area in detail. These priorities strongly echo recommendations from the Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being report,4 as this plan builds on that work and incorporates early lessons and considerations from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The seven priorities include

- Create and sustain positive work and learning environments and culture. Transform health systems, health education, and training by prioritizing and investing in eff orts to optimize environments that prevent and reduce burnout, foster professional well-being, and support quality care (NASEM, 2019).

- Invest in measurement, assessment, strategies, and research. Expand the uptake of existing tools at the health system level and advance national research on decreasing health worker burnout and improving well-being.

- Support mental health and reduce stigma. Provide support to health workers by eliminating barriers and reducing stigma associated with seeking services needed to address mental health challenges.

- Address compliance, regulatory, and policy barriers for daily work. Prevent and reduce the unnecessary burdens that stem from laws, regulations, policies, and standards placed on health workers.

- Engage effective technology tools. Optimize and expand the use of health information technologies that support health workers in providing high-quality patient care and serving population health, and minimize technologies that inhibit clinical decision-making or add to administrative burden.

- Institutionalize well-being as a long-term value. Ensure COVID-19 recovery eff orts address the toll on health worker wellbeing now and in the future, and bolster the public health and health care systems for future emergencies.

- Recruit and retain a diverse and inclusive health workforce. Promote careers in the health professions and increase pathways and systems for a diverse, inclusive, and thriving workforce

Transforming the U.S. health system is a complex challenge, and imagining the journey toward a thriving health workforce can be daunting.

Nevertheless, important steps continue to be made.

For example, following the death of Dr. Lorna Breen, her family rallied policymakers and other key stakeholders to successfully lead the passage of the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act in 2022, which begins to support the mental and behavioral health of health workers (117th Congress, 2021).

This is a major indicator of progress toward a health system that better serves both patients and health workers.

Everyone — from health workers to the public to multi-sectoral leaders — has a role in tackling health workforce well-being (see Figure 1)

However, in the wake of COVID-19 and its impacts on the health workforce, the nation is experiencing a cultural shift, where every actor must take ownership of their role and join in building a social movement for health workforce well-being (Kahan and Avritt, 2015).

This National Plan is a crucial component that will help coordinate actions across the fi eld and provide a roadmap for developing a system of accountability to monitor eff orts and track progress on advancing health worker well-being.

Through the collective work among organizations and individuals committed to reversing trends in health worker burnout, particularly over the past six years, many of the foundational pieces are in place to begin a social movement to advance health worker well-being.5

The priorities, goals, and actions laid out in the National Plan are urgent and complex.

No single actor or sector can move the needle on its own, and change will not happen overnight.

But such complexity cannot be an excuse for inaction. Every actor and sector should identify the most pressing priorities or promising opportunities and develop plans for near-, medium-, and long-term actions in accordance with available resources and in collaboration with other actors. This is difficult work, but we must remain collectively committed.

Now is the time to re-establish the social contract between health workers and society.

This mutual agreement and understanding calls on health workers to fulfill their roles as healers.

In exchange, society grants trust in the health professions, provides the ability for professions to self-govern, and shares in the responsibility for improving public health and maintaining health infrastructure and systems (Khan et al., 2022).

The health of the nation depends on it.

Now is the time to re-establish the social contract between health workers and society. This mutual agreement and understanding calls on health workers to fulfill their roles as healers.

Other sections

See the original publication (this is an excerpt version only)

Summary and Conclusion

No single actor is responsible for making the significant investments needed to ensure sustainable, system-wide changes and to achieve the vision set out in this National Plan.

Investment in health worker well-being must come from multiple levels.

These actions must include individual health systems and training programs — both large and small — committing to a baseline understanding of burnout and distress in their workforce.

Then, interventions must be implemented with frontline health workers that include

- public and private payers streamlining processes and requirements,

- providing reimbursements for mental health care, and supporting efforts to enhance well-being;

- developers of health IT improving EHRs and innovating to be more human-centered;

- and federal and state governments investing in wide scale research, as well as tracking and removing barriers to allow funding to flow to work and learning environments.

The goals, actions, and actors identified in this National Plan are interconnected and aim to support health worker well-being and a thriving U.S. health system.

Improving health worker well-being is a shared responsibility that requires collective action by all actors in the U.S. health system and those who influence the systems that support health.

Health leaders play an important role in their institutions and must work together with frontline health workers to address barriers to well-being.

Community members, from patients to the public, private and non-profi t institutions to media organizations, are also called upon to join this burgeoning social movement for health worker well-being and start spreading change on a massive scale.

Leaders of health, public health, and educational institutions must understand the extent and drivers of workplace stress and burnout at the organizational level.

Frontline health workers and learners are vital partners for implementing context-specific interventions that will create safe and supportive work and learning environments.

Our health workers and learners cannot be expected to work in violent, threatening, and unsafe conditions, or be made to feel unwelcome in environments that are not diverse, equitable, inclusive, and accessible.

As a nation, we must understand the effects of COVID-19 and public health crises on the well-being of the health workforce, protect their mental health, and reduce the stigma associated with speaking about these issues now and in the future.

At the national level, policies, payment structures, and other key systems governing care and disease prevention must align to focus on human connection and trust in health care.

We must review and revise our technology, rules, regulations, and policies to streamline care and reduce the burden in service of the critical health worker-patient relationship.

We must institutionalize well-being as a value to ensure the health and longevity of those who care for us and train, hire, and retain a health workforce that reflects the diversity of the U.S. population.

Much like how the national movement to improve the safety and quality of care delivery has gained ground over the last 20 years, improving health worker well-being will be a long journey.

While there is no finish line, every step makes a difference in improving the environment for our health workforce and brings us closer to experiencing a health system where both health workers and patients thrive.

How will the nation know we are on the right path?

Key indicators of progress are more health systems using validated surveys to track health worker well-being and burnout, and training programs that integrate health worker well-being into their strategic plans and educational curricula.

Key indicators of progress are more health systems using validated surveys to track health worker well-being and burnout, and training programs that integrate health worker well-being into their strategic plans and educational curricula

Other signs of positive change at the national level include increased funding streams and evidencebased policy making that support health workforce well-being, and the design, deployment, and accessibility of human-centered technologies that increase the efficiency and safety of the health workforce and simultaneously enhance patient care.

Other signs of positive change at the national level include increased funding streams and evidencebased policy making that support health workforce well-being, …

… and the design, deployment, and accessibility of human-centered technologies that increase the efficiency and safety of the health workforce and simultaneously enhance patient care.

Where do we go from here?

An ecosystem of actors that work collectively to coordinate, facilitate, report, and enable accountability will be necessary for long-term change.

A coalition should catalyze action across professions, settings, and regions; fairly represent all health professions; and unequivocally embrace the principles of diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility.

With this National Plan, the key elements to create a social movement for health workforce well-being in the United States are identified, and we must seize this COVID-19 crisis as a window of opportunity (see Chapter 1).

Next will be a focus on the voices of newly committed and re-committed actors to spark widespread change, advocacy of the actions outlined in this National Plan, and mass communication eff orts to amplify the messages of this National Plan.

This moment demands urgency.

Challenges to health worker well-being were documented prior to the pandemic, and COVID-19 has only deepened these issues and led to a health workforce that is too small and has high levels of burnout and distress.

We cannot witness and not act, as our health workers continuing to sound the alarm for reprieve from the multitude of stressors that have strained and drained our health workforce.

Immediate and sustained action to address health worker burnout and improve wellbeing is imperative to ensure that the United States has a health workforce that can support our population now and in the future.

While we have made progress, more commitment and investment are necessary for sustainable change.

Improving health worker well-being is a societal issue — it is our ethical obligation to take action to protect those who care for all of us

Contributor(s):

National Academy of Medicine; Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience; Victor J. Dzau, Darrell Kirch, Vivek Murthy, and Thomas Nasca, Editors

Names mentioned

AHA President and CEO Rick Pollack and AHA Chief Nursing Officer Robyn Begley, CEO of the American Organization for Nursing Leadership