the health strategist

institute for health strategy and digital health

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Chief Researcherm , Editor and Strategy Officer (CSO)

April 30, 2023

ONE PAGE SUMMARY

There is an increase in mental health issues around the world triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and discusses how governments are responding.

- A 2021 Ipsos survey found mental health to be the second-biggest health concern overall across 34 countries, with several countries like the United States, Chile, and Spain ranking it as the top concern.

- Many of these countries were already in the throes of a mental health crisis before the pandemic.

- Japan, has one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

Some countries have taken steps to expand access to mental health services, including

- the Netherlands, which requires all primary care offices to provide mental health services to patients with mild-to-moderate mental health issues, resulting in improved patient outcomes.

- Australia updated its national policy framework to improve access to mental health care and supporting services across all states and territories.

- Norway piloted a program called Prompt Mental Health Care in 2012 to expand access, which resulted in improved patient outcomes and has now been rolled out across the country.

- The Biden administration has also announced a national strategy to increase the mental health care workforce and connect more Americans to care.

Policymakers must decide whether to stick with the status quo or strengthen mental health services to ensure everyone can get the care they need without barriers.

Mental Health Is a Top Concern Around the World. How Are Governments Responding?

The Commonwealth Fund

Reginald D. Williams II.

April 28, 2023

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a rapid increase in mental health issues around the world.

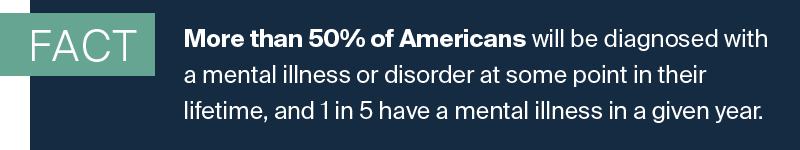

An Ipsos survey fielded in 2021 found mental health was the second-biggest health concern overall across 34 countries; in Chile, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United States, it was the top concern. In fact, a third of all Americans are struggling to cope with stress, anxiety, or sadness, according to a 2020 Commonwealth Fund survey.

Many of these countries were already in the throes of a mental health crisis before the pandemic.

For instance, suicide rates in the United States — the highest in the world — have been rising for nearly 20 years.

A handful of the countries surveyed have taken steps to expand access to mental health services, including by integrating them more easily into routine care.

It should be noted that these countries, unlike the U.S., have universal health care coverage.

- In 2014, the Netherlands required all primary care offices to provide mental health services to patients with mild-to-moderate mental health issues, primarily by hiring psychologists, nurses, and social workers. By 2020, 94 percent of Dutch primary care physicians reported having mental health providers in their practices, compared to just a third of physicians in the U.S. This has allowed psychiatrists and other, more specialized, mental health providers to focus on those with more complex psychiatric disorders. One study found that as a result, most patients with mental health problems were either treated in a primary care office or a less specialized care practice, with only 13 percent referred to more specialized care. Research shows that when patients were referred to the appropriate place of care based on their conditions, they saw improvements in symptoms after just three months.

- Last year, Australia updated its national policy framework to improve access to mental health care and supporting services across all states and territories. This includes integrating mental health care with other health and social services, such as housing and social care; developing initiatives to attract, train, and retain a mental health workforce; and establishing community-managed organizations to deliver mental health care alongside public health workers and primary care providers. Research shows these types of reforms can help reduce the prevalence of mental health conditions, but Australia’s initiative remains underfunded.

- Norway historically had a high rate of mild to moderate mental health conditions, but few Norwegians received care. A program known as Prompt Mental Health Care was piloted in 2012 with the goal of expanding access by limiting appointment wait times to 48 hours, allowing patients to see mental health providers without a referral, and offering guided self-help courses and group therapy. A randomized controlled trial found program participants were more likely to report reduced symptoms of anxiety or depression after six months compared to those who received standard care, where wait times could be as long as 12 weeks. The program has now been rolled out in roughly 50 sites across the country.

The potential value of these approaches for the United States is self-evident, but even countries where people largely do not see mental health as a significant problem, like Japan and France, stand to benefit from expanding access to services.

It’s possible that such perceptions are a function of high levels of stigma around mental health issues — Japan, in fact, has one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

Last year, the Biden administration announced a national strategy to increase the mental health care workforce and connect more Americans to care. As a start, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that doctors screen all adult patients under age 65 for anxiety. But there is a long way to go: half of Americans with mental health conditions skip or delay needed care because of costs. In adults age 65 and older, research demonstrates that mental health conditions alongside chronic conditions leads to a significant increase in health care spending.

Countries around the world are at a critical juncture.

Policymakers can stick with the status quo, leaving those struggling to cope with recent traumas and enduring stressors without support, or they can strengthen mental health services to ensure everyone can get the care they need, without barriers.

The author thanks Shanoor Seervai, Munira Gunja, and Evan Gumas for their contributions.

Source: CWF Newsletter, April 2023