the health strategist

research institute for health strategy

and digital health

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Chief Research and Strategy Officer (CRSO),

Chief Editor and Senior Advisor

August 23, 2023

What is the message?

According to a recent article, published by Gavi – The Vaccine Alliance, climate change is expected to trigger a 20% increase in cases of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya over the next three decades, with higher temperatures driving the spread of these diseases in cooler regions like southern Brazil and southern Europe.

A study, developed by the Center for Arbovirus Emergency Operations, also highlights the potential for longer transmission seasons and wider geographical areas for disease occurrence.

The loss of biodiversity due to deforestation further exacerbates disease transmission, emphasizing the need to replant rainforests to curb the proliferation of disease-carrying mosquitoes in urban areas.

Key takeaways:

- What does the new study predict about the transmission of viruses like dengue, Zika, and chikungunya due to climate change?

The study forecasts a 20% increase in cases of viruses such as dengue, Zika, and chikungunya over the next 30 years due to climate change. The diseases carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito are expected to spread more in cooler regions like southern Brazil and southern Europe due to higher temperatures.

- What were the dengue-related statistics for Brazil in recent years?

In 2022, Brazil experienced a record-high number of dengue-related deaths, surpassing 1,000 for the first time in history. By June 11 of 2023, there had already been a 22% increase in fatal cases compared to the same period in the previous year. The total number of probable cases in 2023 was 1.3 million, whereas 2022 saw 1,450,270 cases.

- How does the study from the University of Michigan predict the impact of climate change on disease transmission?

The University of Michigan study analyzed disease incidence in four Brazilian cities and concluded that arboviruses’ transmission potential, including dengue, Zika, and chikungunya, could increase by 20% over the next 30 years due to climate change. This could lead to longer transmission seasons and wider geographic spread of these diseases.

- What does the term “basic reproduction number” (R0) refer to in the context of disease transmission?

The basic reproduction number, or R0, represents the estimated number of new cases of a disease that mosquitoes would cause in a susceptible population after biting and infecting one person. It’s a key parameter to assess disease transmission potential.

- How might climate change affect the transmission of Zika and dengue in different Brazilian cities?

Climate change could lead to a higher basic reproduction number (R0) for diseases like Zika. For example, in Manaus, the R0 for Zika is projected to increase from 2.3 to around 2.5 by 2050. Even small changes in R0 can lead to larger and faster-spreading outbreaks.

- How does the study suggest that the seasons for disease spread will change in various Brazilian cities by 2050?

The study indicates that Rio de Janeiro’s disease transmission season could extend by two to three months, while Recife’s could extend by two months by 2050. São Paulo, with its lower temperatures, might become more vulnerable to outbreaks between November and April.

- What is the relationship between arboviruses spreading to cooler regions and human transportation?

Arboviruses are increasingly spreading to cooler regions, not only due to higher temperatures caused by climate change but also because they are being transported more frequently by road vehicles and airplanes between medium- and large-sized cities in Brazil.

- How does deforestation impact the transmission of diseases like dengue and Zika?

Loss of biodiversity due to deforestation creates conditions conducive to increased numbers of dengue and Zika cases. A study suggests that forests act as barriers to the establishment of the Aedes aegypti mosquito population. When biodiversity decreases, it creates an ideal environment for the mosquito to thrive and reproduce.

- What solution does the study propose for controlling the proliferation of the Aedes aegypti mosquito in urban areas?

Replanting rainforests within cities and surrounding areas can help control the proliferation of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Forest corridors attract other mosquito species that don’t transmit diseases and compete with Aedes aegypti. Well-maintained and preserved forests can fragment the mosquito population and limit its growth.

DEEP DIVE

Zika, dengue transmission expected to rise with climate change

A new study foresees a 20% increase in cases of viruses like dengue, Zika and chikungunya over the next 30 years due to climate change. Higher temperatures are already causing the diseases carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito to spread in cooler regions like southern Brazil and southern Europe

Gavi – The Vaccine Alliance

Luís Patriani

August 18, 2023

The Aedes aegypti mosquito transmits viruses like dengue, Zika and chikungunya. Photo by Muhammad Mahdi Karim, GFDL 1.2, via Wikimedia Commons

The number of deaths in Brazil due to dengue hit a record high in 2022, with 1,016 — the first time in history the number had surpassed four digits. And the sobering statistic is expected to be even higher in 2023.

According to the Center for Arbovirus Emergency Operations, 635 fatal cases had been reported by June 11 — up 22% as compared with the same period in 2022. The agency’s most recent update, released by the Ministry of Health, shows 1.3 million probable cases so far this year, while the total number for 2022 was 1,450,270 cases.

If the threat of dengue, which is mostly transmitted by the female Aedes aegypti mosquito, seems frightening now, a study carried out at the University of Michigan in the United States painted a worse picture for the future. The transmission potential of arboviruses — which include, aside from dengue, Zika and chikungunya — could increase by 20% over the next 30 years because of climate change.

The study arrived at this alarming conclusion after analyzing the incidence of these diseases in four Brazilian cities: Manaus, Recife, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

“Brazilian health agencies need to be prepared not only for the increased incidence of diseases like dengue and Zika, but also for longer transmission seasons and broader geographic areas of occurrence,” affirms epidemiologist Andrew Brouwer, co-author of the study and researcher at the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Image by Felipe Fittipaldi/Wellcome Photography Prize 2019 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0).

More outbreaks in cooler regions

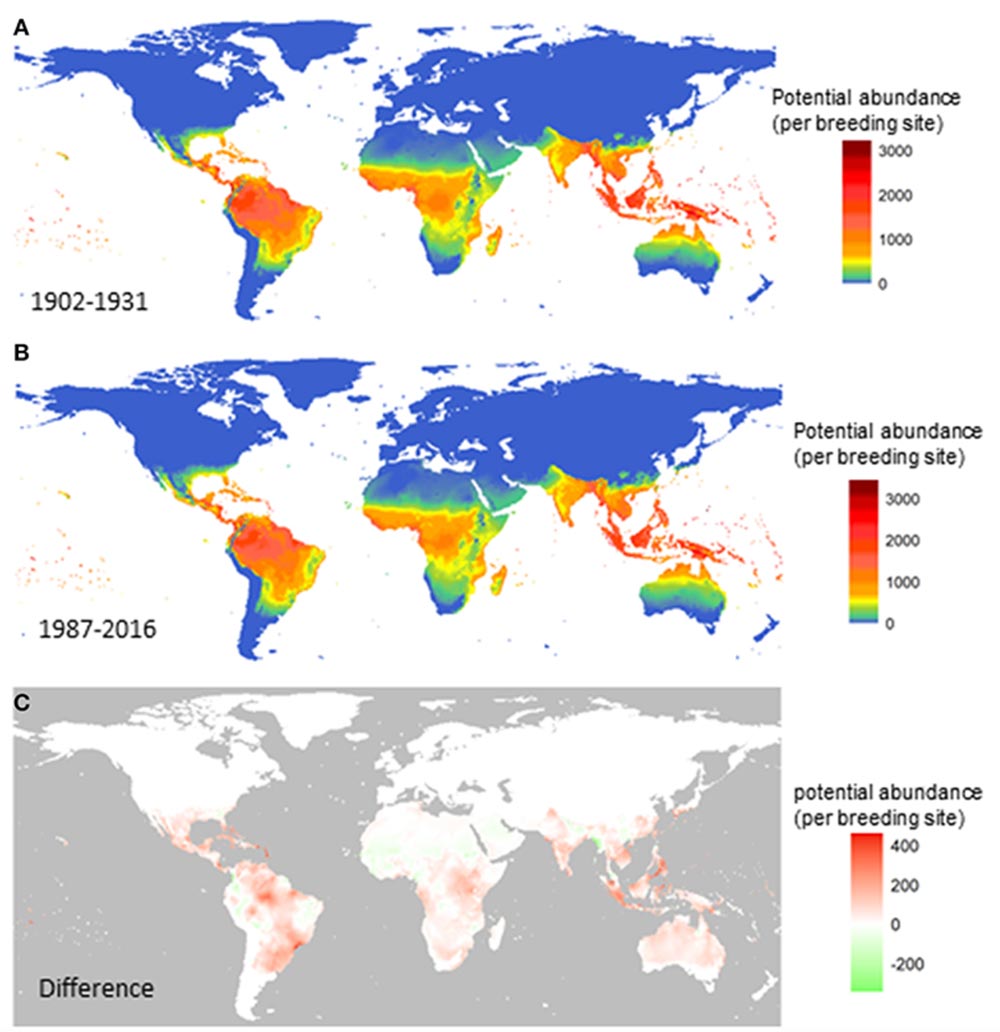

To comparatively measure the epidemic potential of Zika and dengue, the scientists first estimated the number of new cases that mosquitos would cause in a susceptible population after biting and infecting one person, a figure known as the basic reproduction number, or R0. They then used historical data and temperature projections for the years 2045-49 to predict the risk of the diseases.

According to Brouwer, one example of what the increase in basic reproduction number could mean in practice became evident in the case of Manaus, where the current average R0 for Zika is 2.3. This means that one person could infect 2.3 people. In Manaus, this number is expected to grow to around 2.5 by 2050. “This change in the R0 seems small, but it can quickly elevate the transmission chains and lead to larger, faster-spreading outbreaks.”

The study showed greater potential for Zika epidemics than current levels in all the climatic scenarios that it analyzed, including Manaus, where the threat had been expected to drop because of extreme heat. Zika and dengue spread most quickly at average daily temperatures around 30° Celsius, but outbreaks are still possible at 35°C.

The study also showed that the seasons in which the diseases spread will be longer by two or three months in Rio de Janeiro and by two months in Recife by 2050 — up from the current four months a year during which the most outbreaks occur (from December through March). Because temperatures there are lower, São Paulo is at lower risk for spread of the diseases but may become more vulnerable to outbreaks between November and April.

“We were expecting a consistent drop in the projections for risk of arboviral diseases in for the hottest regions of the country, but most of the scenarios showed higher levels than we have today. There will probably be sporadic outbreaks in the coolest regions that will become increasingly common as temperatures rise,” said Brouwer.

Arboviruses are already spreading to cooler regions today, driven not only by higher temperatures but by the fact that they are transported more frequently by roadway vehicles and airplanes traveling between Brazil’s medium- and large-sized cities.

This fact is evidenced by data on the states with the most deaths in 2022: São Paulo (282 deaths), Goiás (162), Paraná (109), Santa Catarina (88) and Rio Grande do Sul (66). The city of Joinville, located in the southern — and cooler — state of Santa Catarina, ranked fourth among the Brazilian cities with the most cases of dengue, with 21,300.

Image courtesy of Liu-Helmersson et al. (2019).

More forest, less disease

One of Brazil’s leading public health specialists, Christovam Barcellos, who is head researcher at the Fiocruz Health Communication, Technology and Scientific Information Institute’s Health Information Laboratory (LIS/ICICT), explained how the dengue transmission scenario is changing.

“All the traditional studies on dengue looked at high temperatures and rainfall, but this pattern is changing,” said Barcellos. “Rainfall isn’t the only factor affecting dengue. Drought can also produce the disease, because people begin to store water inside their homes, bringing the enemy in with it. In southern Brazil, for example, we had many years of La Niña [a seasonal phenomenon when currents in the Pacific Ocean are cooler], which led to a strong drought — no rain and a high temperature. It was an unprecedented situation. Dengue spread like wildfire in those regions.”

Barcellos is also one of Brazil’s coordinators of the international Harmonize project, funded by the Wellcome Trust fund. Harmonize will study how climate changes may alter incidence patterns of illnesses transmitted by mosquitos. According to him, “tropical diseases are spreading to temperate zones. I met with a group of French researchers who are quite concerned with the presence of Aedes aegypti in southern Europe. They are seeking to learn how to deal with a possible epidemic from us.”

Image courtesy of Paulo H. Carvalho/Agência Brasília.

The loss of biodiversity due to deforestation is another factor that scientists now see as fundamental in explaining increased numbers of dengue and Zika cases.

One study carried out by researchers at four universities in the state of Minas Gerais found that, despite what is commonly thought about the correlation between forests and tropical diseases, rainforests are, in fact, one of the most important tools in combatting A. aegypti.

“Aedes aegypti can’t even establish a population in forests. It can only survive in environments with fewer competitors and no predators. It doesn’t cohabitate well with Brazilian biodiversity. But when this biodiversity is reduced, a perfect niche is created for the mosquito to set up residence and reproduce,” explained Sérvio Pontes Ribeiro, head researcher at Ouro Preto Federal University’s Forests and Disease Ecology Laboratory and one of the people responsible for the study.

According to Ribeiro, one important solution for fighting the proliferation of this mosquito in urban areas is to replant rainforest inside the city and in surrounding areas. “Forest corridors attract birds and other mosquito species that don’t transmit the disease and compete with Aedes aegypti. Well-maintained and preserved forests fragment the mosquito’s population and end up dissolving it.

English article originally published at https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork

This story was reported by Mongabay Brasil team and first published here on Brazilian site on July 17, 2023.