BCG – Boston Consulting Group

By Ben Horner, Wouter van Leeuwen, Maggie Larkin, Julia Baker, and Stefan Larsson

SEPTEMBER 03, 2019

This is an excerpt from the report “Paying for Value in Health Care” published in September 2019, based on the chapter: “Building a Value Based Payment System” edited by Joaquim Cardoso.

(VBHC: Value Based Health Care)

Building a Value-Based Payment System

Although the specific approach will, of course, vary depending on the starting point and organization of a given health system, we recommend that health system leaders begin building a value-based payment system by focusing on three strategic interventions.

These include creating incentives to:

- 1.Manage the total cost and quality of the health system, which is critical for encouraging providers to prioritize wellness and disease prevention

- 2.Optimize the value of routine specialist care, which are a predictable and relatively high-cost component of any health system, and

- 3.Optimize the value of complex, acute, inpatient care, which is a major source of fixed costs for any health system

Incentives to Optimize the Value of Routine Specialist Care

At any moment in time, a subset of a health system’s patients require specialized care. And in every system, certain episodes of care happenb appropriate referral, treatment, and, when possible, recovery.

The best approach is to develop bundled payments that cover all the providers in the care pathway for the given clinical episode and create incentives for a collaborative, team-based approach to care. In developing a system-wide approach to bundled payments, it’s best to begin with situations that meet the following criteria:

- The episode of care has a clear profile or a clinically defined start pointbb patient for joint replacement who would be better served by physical therapy).

- The care pathway has significant variation in outcomes and costs acrossb patients, and established protocols exist for reducing that variation. Therefore, the episode of care is a promising candidate for improved valueb through innovation and process redesign.

- Providers are able to control the setting of care and, therefore, influence the care pathway. Some episodes of care, such as trauma care, may beb sources of high cost and considerable practice and outcome variation, but the wide variety of patient situations where trauma care is required andb care pathway makes trauma a poor candidate for bundled payments.

- The episode of care represents a significant expense to the health system as a whole (to make it worth the investment of time and effort on the part of payers) and significant volume (to make it worth the investment of providers).

In health systems with multiple payers, a key challenge will be to create common definitions for a given episode. Otherwise, providers will have to adapt to multiple bundled-payment models, adding to system complexity. We believe that there is a great deal that health systems can learn from the leaders in the field. Over time, we expect that the bundled payment model will be standardized for specific clinical episodes and patient groups and adopted by health systems around the world.

Incentives to Optimize the Value of Complex, Acute, Inpatient Care

Whether in a metropolitan area, a region, or across an entire nation, any health system has to fund an extensive fixed-cost infrastructure of hospitals and other facilities to deal with complex cases and acute emergency care. Planning for this infrastructure has two main challenges: estimating the likely needs of the patient population and treating patients in the setting that is best both for patient health and system costs.

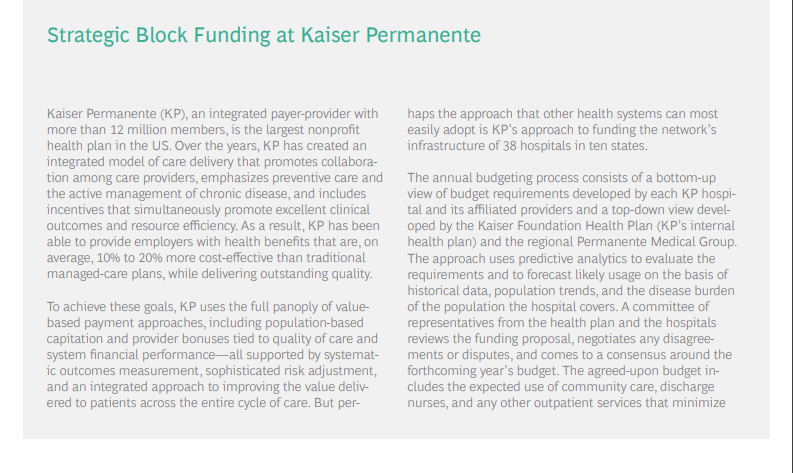

Typically, the cost of complex and acute inpatient care has been covered through some combination of activity-based payments and block funding, which is determined on the basis of the hospital’s historical capacity, the size of the population it serves, and its specific role in the health system (for example, an academic medical center with special responsibility to train doctors and innovate experimental types of treatment, or a rural hospital with a mission to deliver acute care in underpopulated regions).

These traditional funding approaches have not typically focused on value. Activity-based payments reimburse hospitals for the procedures performed, rewarding for volume. And population-based or role-based block funding has typically been linked to the number of beds in the facility, rather than a true estimate of the health needs of the population that the hospital serves. Further, traditional payment approaches are rarely tied to patient outcomes, and as a result, are ineffective incentives for value-based care. In fact, they can contribute to a system that relies excessively on expensive hospital care and maintains excess capacity.

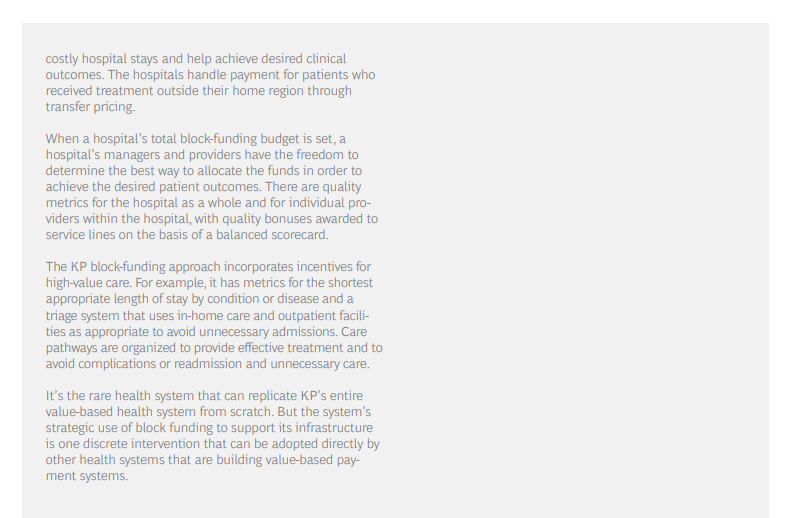

With careful design, however, block funding can be transformed into a strategic intervention for building a value-based payment system.

First, instead of assigning funding levels by facility size, health systems should employ predictive analytics to estimate likely usage levels on the basis of the demographic, disease, and risk profiles of a region’s population. (Safeguards can also be put in place to protect provider budgets against unusually high costs associated with specialized care that is difficult to predict-for example, major trauma.)

A forward-looking rather than historical estimate of demand in critical patient populations can be an effective way to manage capacity; plan for scheduling, training, and clinical education; and adjust to new innovations in care delivery.

Second, instead of conceiving of block funding as limited to the hospital setting, health systems should extend the scope of such funding to settings across the entire network of care. Taking this step creates an incentive for providers to direct demand to the most appropriate and cost-effective site of care-for example, outpatient clinics, community-care facilities, or in-home care with remote monitoring.

In this approach, regional hospitals function less as the main site of care and more as a hub in a network. And hospital-based specialist providers become, in effect, general contractors who are responsible for finding the most cost-effective and highest-quality site of care across the entire value chain, contracting with outpatient facilities and working with specialists-such as discharge nurses, visiting nurses, and home health aides-to minimize the total cost of care. Block funding is the approach taken, for example, by Kaiser Permanente, to fund its infrastructure of 38 hospitals in ten states. (See the sidebar “Strategic Block Funding at Kaiser Permanente.”)

Some Common System Challenges

As health systems pursue these interventions, they will also face at least three system-wide challenges. The first is defining the necessary linkages among the payment models. The second is developing measurement systems for tracking health outcomes and costs and building the advanced analytics platform necessary both to feed data to providers and use it as a basis for value-based payments. The third is creating systems to manage risk, both in terms of patient mix and providers’ financial exposure.

In the course of a lifetime, patients will have different needs covered by different value-based payment models. Health system leaders will need to design systems for managing these models across different patient populations and different types of providers. These systems will need to be sufficiently comprehensive but not so complex that they become unmanageable. The principal should be to make the system as simple as possible for patients and providers, while managing complexity through back-end IT systems.

Critical choices and tradeoffs will also need to be made around issues such as deciding where to focus a health system’s bundled payment initiatives, how to organize provider payments for patients suffering from multiple morbidities, and what kind of data and advanced-analytics platforms and visualization tools will be necessary to provide the insights necessary to drive continuous improvement of patient value.

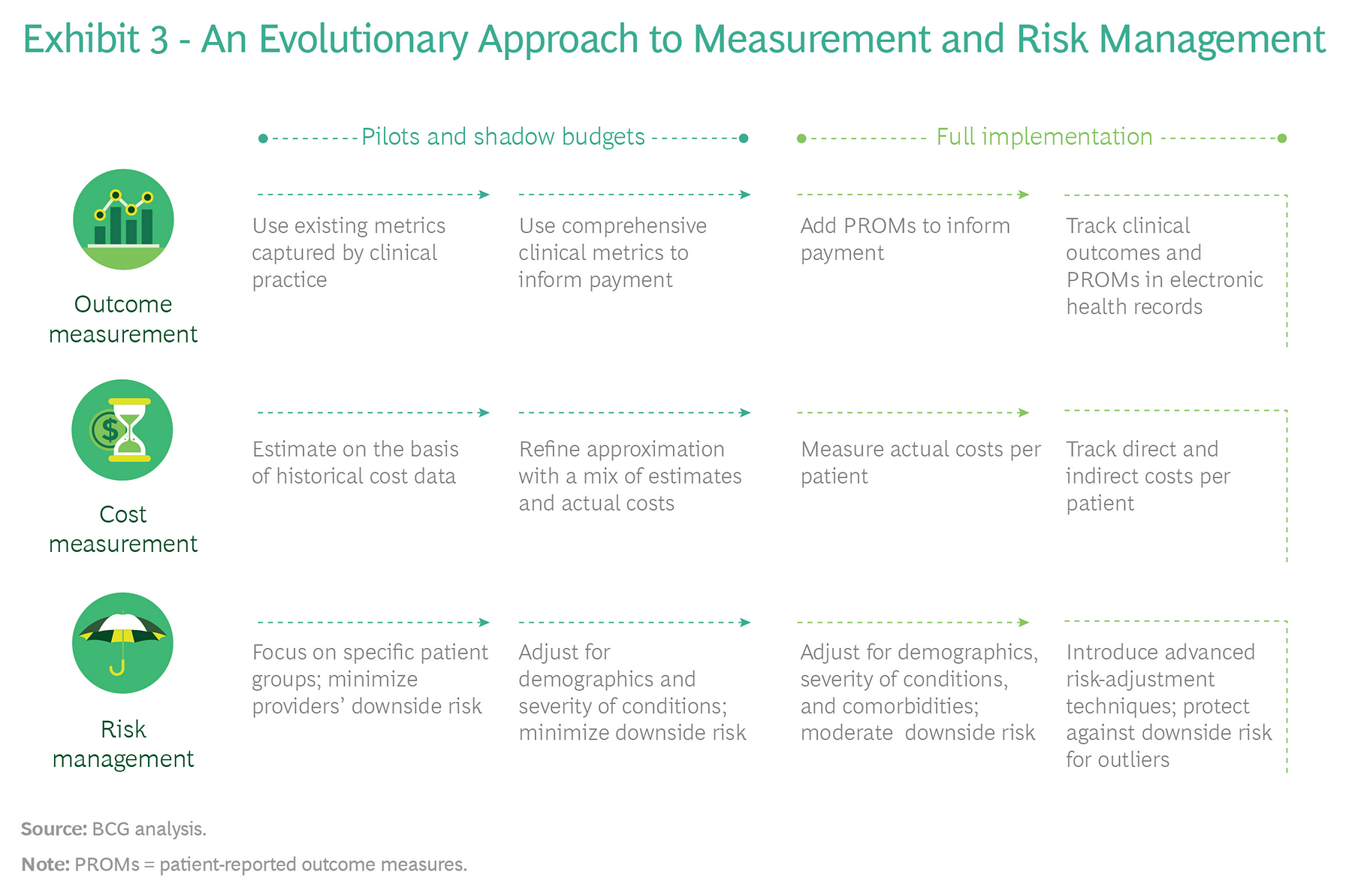

When it comes to measuring outcomes and cost and managing risk, we recommend an evolutionary approach. Health systems don’t have to wait until they have advanced-measurement and risk-adjustment systems in place to get started. Rather, they can begin by using the metrics and methodologies they have, investing in and learning from pilots, and then refining their current systems before implementing payment models system-wide.

For example, to measure health outcomes, start by using existing metrics that are already captured in clinical practice; then, over time, develop advanced information systems in order to routinely capture metrics for both clinical and patient-reported outcomes that are in patients’ electronic health records. To track costs, start with estimates that are based on historical data; then, over time, develop systems that track actual direct and indirect costs per patient. In parallel, start piloting the data and analytics platforms that are necessary to collect the data and share it across the system.

To manage risk, initially focus value-based payment models on clearly defined patient groups and exclude downside risk to minimize providers’ financial exposure. Then, over time, gradually introduce more advanced risk-adjustment techniques that allow value-based payment models to be expanded to more complex patient groups (for instance, those with multiple morbidities). And as providers develop the capabilities to manage costs, exclude downside risk only for extreme outlier cases. (See Exhibit 3.)

The appropriate balance between financial and nonfinancial incentives for value-based health care is also likely to evolve over time. In some situations, value-based payments will be the primary catalyst for the long-term reorientation of health systems around value delivered to patients. But as value-based norms and cultures develop in provider organizations, and health systems put in place the analytics to make outcomes and costs transparent, financial incentives may play a less central role.

The point: implementing a value-based payment system is likely to be a dynamic process with considerable experimentation, learning, and adaption. Health system leaders need to be pragmatic and action-oriented. In addition, rather than treat value-based payment in isolation, leaders need to recognize it as one element in a broader set of system-wide changes, designed to align patient, provider, and payer behaviors around the shared goal of improving health care value.

About the authors

Ben Horner, Managing Director & Partner, London

Wouter van Leeuwen, Managing Director & Partner, Amsterdam

Maggie Larkin, Principal, Washington, DC

Julia Baker, Senior Knowledge Analyst, Sydney

About Boston Consulting Group

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders-empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2021. All rights reserved.

Originally published at https://www.bcg.com on January 8, 2021.

To download the PDF version of the full report, open the URL below:

http://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Paying-for-Value-in-Health-Care-September-2019_tcm9-227552.pdf