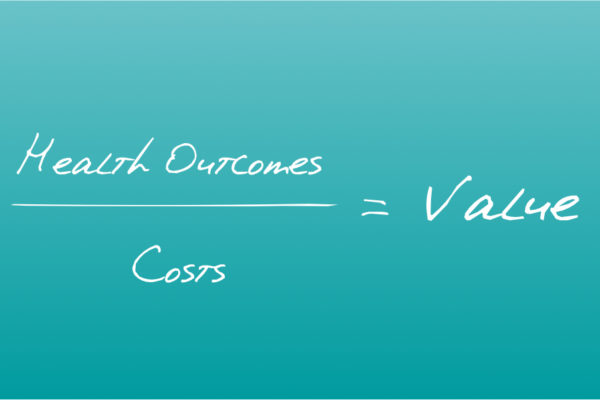

Credit: value equation

Harvard Business Review

Michael Porter and Thomas Lee

October 2013

This is an excerpt of the paper: “The Strategy That Will Fix Health Care“, published in 2013, focused on the topic above.

The Value Agenda Detailed

- IPUs — Organize into Integrated Practice Units (IPUs)

- OUTCOMES & COSTS — Measure Outcomes and Costs for Every Patient

- BUNDLED PAYMENTS — Move to Bundled Payments for Care Cycles

- INTEGRATED CARE — -Integrate Care Delivery Systems

- GEOGRAPHY — Expand Geographic Reach

- IT PLATFORM — Build an Enabling Information Technology Platform

2: Measure Outcomes and Costs for Every Patient

Rapid improvement in any field requires measuring results-a familiar principle in management. Teams improve and excel by tracking progress over time and comparing their performance to that of peers inside and outside their organization. Indeed, rigorous measurement of value (outcomes and costs) is perhaps the single most important step in improving health care. Wherever we see systematic measurement of results in health care-no matter what the country-we see those results improve.

Yet the reality is that the great majority of health care providers (and insurers) fail to track either outcomes or costs by medical condition for individual patients. For example, although many institutions have “back pain centers,” few can tell you about their patients’ outcomes (such as their time to return to work) or the actual resources used in treating those patients over the full care cycle. That surprising truth goes a long way toward explaining why decades of health care reform have not changed the trajectory of value in the system.

When outcomes measurement is done, it rarely goes beyond tracking a few areas, such as mortality and safety. Instead, “quality measurement” has gravitated to the most easily measured and least controversial indicators. Most “quality” metrics do not gauge quality; rather, they are process measures that capture compliance with practice guidelines. HEDIS (the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) scores consist entirely of process measures as well as easy-to-measure clinical indicators that fall well short of actual outcomes. For diabetes, for example, providers measure the reliability of their LDL cholesterol checks and hemoglobin A1c levels, even though what really matters to patients is whether they are likely to lose their vision, need dialysis, have a heart attack or stroke, or undergo an amputation. Few health care organizations yet measure how their diabetic patients fare on all the outcomes that matter.

It is not surprising that the public remains indifferent to quality measures that may gauge a provider’s reliability and reputation but say little about how its patients actually do. The only true measures of quality are the outcomes that matter to patients. And when those outcomes are collected and reported publicly, providers face tremendous pressure-and strong incentives-to improve and to adopt best practices, with resulting improvements in outcomes. Take, for example, the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992, which mandated that all clinics performing assisted reproductive technology procedures, notably in vitro fertilization, provide their live birth rates and other metrics to the Centers for Disease Control. After the CDC began publicly reporting those data, in 1997, improvements in the field were rapidly adopted, and success rates for all clinics, large and small, have steadily improved. (See the exhibit “Outcomes Measurement and Reporting Drive Improvement.”)

Outcomes Measurement and Reporting Drive Improvement

Data Source: Centers for Disease Control

Since public reporting of clinic performance began, in 1997, in vitro fertilization success rates have climbed steadily across all clinics as process improvements have spread.

Measuring outcomes that matter to patients.

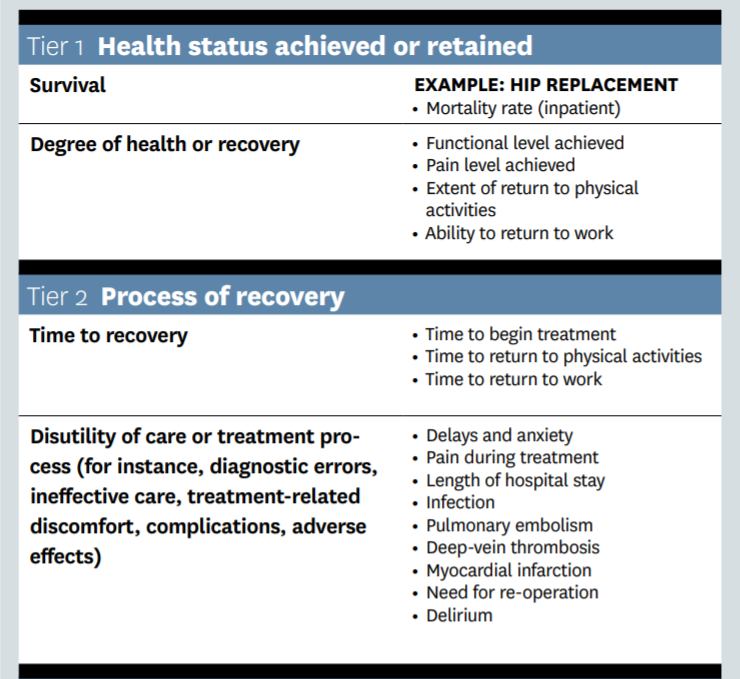

Outcomes should be measured by medical condition (such as diabetes), not by specialty (podiatry) or intervention (eye examination). Outcomes should cover the full cycle of care for the condition, and track the patient’s health status after care is completed. The outcomes that matter to patients for a particular medical condition fall into three tiers. (For more, see Michael Porter’s article “Measuring Health Outcomes: The Outcome Hierarchy,” New England Journal of Medicine, December 2010.)

Tier 1 involves the health status achieved. Patients care about mortality rates, of course, but they’re also concerned about their functional status. In the case of prostate cancer treatment, for example, five-year survival rates are typically 90% or higher, so patients are more interested in their providers’ performance on crucial functional outcomes, such as incontinence and sexual function, where variability among providers is much greater.

In measuring quality of care, providers tend to focus on only what they directly control or easily measured clinical indicators. However, measuring the full set of outcomes that matter to patients by condition is essential in meeting their needs. And when outcomes are measured comprehensively, results invariably improve.

Tier 2 outcomes relate to the nature of the care cycle and recovery. For example, high readmission rates and frequent emergency-department “bounce backs” may not actually worsen long-term survival, but they are expensive and frustrating for both providers and patients. The level of discomfort during care and how long it takes to return to normal activities also matter greatly to patients. Significant delays before seeing a specialist for a potentially ominous complaint can cause unnecessary anxiety, while delays in commencing treatment prolong the return to normal life. Even when functional outcomes are equivalent, patients whose care process is timely and free of chaos, confusion, and unnecessary setbacks experience much better care than those who encounter delays and problems along the way.

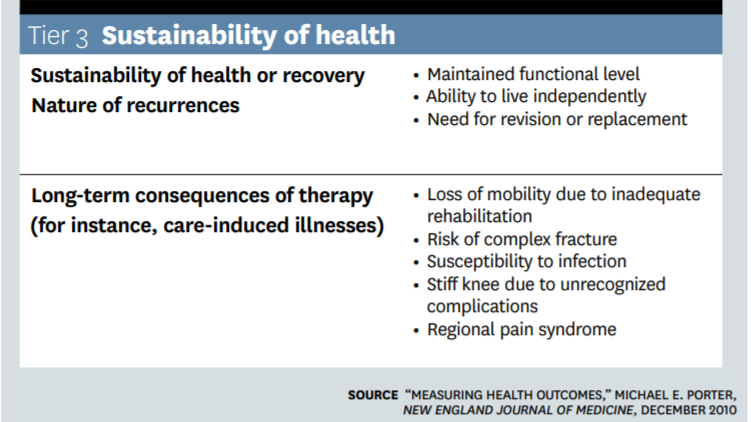

Tier 3 outcomes relate to the sustainability of health. A hip replacement that lasts two years is inferior to one that lasts 15 years, from both the patient’s perspective and the provider’s.

Outcomes That Matter to Patients: A Hierarchy

In measuring quality of care, providers tend to focus on only what they directly control or easily measured clinical indicators. However, measuring the full set of outcomes that matter to patients by condition is essential in meeting their needs. And when outcomes are measured comprehensively, results invariably improve.

Measuring the full set of outcomes that matter is indispensable to better meeting patients’ needs. It is also one of the most powerful vehicles for lowering health care costs. If Tier 1 functional outcomes improve, costs invariably go down. If any Tier 2 or 3 outcomes improve, costs invariably go down. A 2011 German study, for example, found that one-year follow-up costs after total hip replacement were 15% lower in hospitals with above-average outcomes than in hospitals with below-average outcomes, and 24% lower than in very-low-volume hospitals, where providers have relatively little experience with hip replacements. By failing to consistently measure the outcomes that matter, we lose perhaps our most powerful lever for cost reduction.

Over the past half dozen years, a growing array of providers have begun to embrace true outcome measurement. Many of the leaders have seen their reputations-and market share-improve as a result. A welcomed competition is emerging to be the most comprehensive and transparent provider in measuring outcomes.

The Cleveland Clinic is one such pioneer, first publishing its mortality data on cardiac surgery and subsequently mandating outcomes measurement across the entire organization. Today, the Clinic publishes 14 different “outcomes books” reporting performance in managing a growing number of conditions (cancer, neurological conditions, and cardiac diseases, for example). The range of outcomes measured remains limited, but the Clinic is expanding its efforts, and other organizations are following suit. At the individual IPU level, numerous providers are beginning efforts. At Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s Spine Center, for instance, patient scores for pain, physical function, and disability for surgical and nonsurgical treatment at three, six, 12, and 24 months are now published for each type of low back disorder.

Providers are improving their understanding of what outcomes to measure and how to collect, analyze, and report outcomes data. For example, some of our colleagues at Partners HealthCare in Boston are testing innovative technologies such as tablet computers, web portals, and telephonic interactive systems for collecting outcomes data from patients after cardiac surgery or as they live with chronic conditions such as diabetes. Outcomes are also starting to be incorporated in real time into the process of care, allowing providers to track progress as they interact with patients.

To accelerate comprehensive and standardized outcome measurement on a global basis, we recently cofounded the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. ICHOM develops minimum outcome sets by medical condition, drawing on international registries and provider best practices. It brings together clinical leaders from around the world to develop standard outcome sets, while also gathering and disseminating best practices in outcomes data collection, verification, and reporting. Just as railroads converged on standard track widths and the telecommunications industry on standards to allow data exchange, health care providers globally should consistently measure outcomes by condition to enable universal comparison and stimulate rapid improvement.

Measuring the cost of care.

For a field in which high cost is an overarching problem, the absence of accurate cost information in health care is nothing short of astounding. Few clinicians have any knowledge of what each component of care costs, much less how costs relate to the outcomes achieved. In most health care organizations there is virtually no accurate information on the cost of the full cycle of care for a patient with a particular medical condition. Instead, most hospital cost-accounting systems are department-based, not patient-based, and designed for billing of transactions reimbursed under fee-for-service contracts. In a world where fees just keep going up, that makes sense. Existing systems are also fine for overall department budgeting, but they provide only crude and misleading estimates of actual costs of service for individual patients and conditions. For example, cost allocations are often based on charges, not actual costs. As health care providers come under increasing pressure to lower costs and report outcomes, the existing systems are wholly inadequate.

To determine value, providers must measure costs at the medical condition level, tracking the expenses involved in treating the condition over the full cycle of care. This requires understanding the resources used in a patient’s care, including personnel, equipment, and facilities; the capacity cost of supplying each resource; and the support costs associated with care, such as IT and administration. Then the cost of caring for a condition can be compared with the outcomes achieved.

The best method for understanding these costs is time-driven activity-based costing, TDABC. While rarely used in health care to date, it is beginning to spread. Where TDABC is being applied, it is helping providers find numerous ways to substantially reduce costs without negatively affecting outcomes (and sometimes even improving them). Providers are achieving savings of 25% or more by tapping opportunities such as better capacity utilization, more-standardized processes, better matching of personnel skills to tasks, locating care in the most cost-effective type of facility, and many others.

For example, Virginia Mason found that it costs $4 per minute for an orthopedic surgeon or other procedural specialist to perform a service, $2 for a general internist, and $1 or less for a nurse practitioner or physical therapist. In light of those cost differences, focusing the time of the most expensive staff members on work that utilizes their full skill set is hugely important. (For more, see Robert Kaplan and Michael Porter’s article “How to Solve the Cost Crisis in Health Care,” HBR September 2011.)

Without understanding the true costs of care for patient conditions, much less how costs are related to outcomes, health care organizations are flying blind in deciding how to improve processes and redesign care. Clinicians and administrators battle over arbitrary cuts, rather than working together to improve the value of care. Because proper cost data are so critical to overcoming the many barriers associated with legacy processes and systems, we often tell skeptical clinical leaders: “Cost accounting is your friend.” Understanding true costs will finally allow clinicians to work with administrators to improve the value of care-the fundamental goal of health care organizations.

About the authors

Michael E. Porter, is the Bishop Lawrence University Professor at Harvard University. He is based at Harvard Business School.

Thomas H. Lee, is the chief medical officer at Press Ganey and the former network president of Partners HealthCare

A version of this article appeared in the October 2013 issue of Harvard Business Review.

Originally published at https://hbr.org on October 1, 2013.