Water-related disasters and their health impacts: A global review

Progress in Disaster Science (Elsevier)

Jiseon Lee, Duminda Perera, Talia Glickman, LinaTaing

August, 2020

Water-borne diseases.

Water-borne diseases are illnesses caused by pathogenic microorganisms often during bathing, washing, drinking, eating, or any other activity where humans have contact with contaminated water. These mainly include diarrheal, respiratory, and skin diseases.

Contaminated water supplies increase the risk of exposure to and transmission of water-borne disease[1] [2] [3].

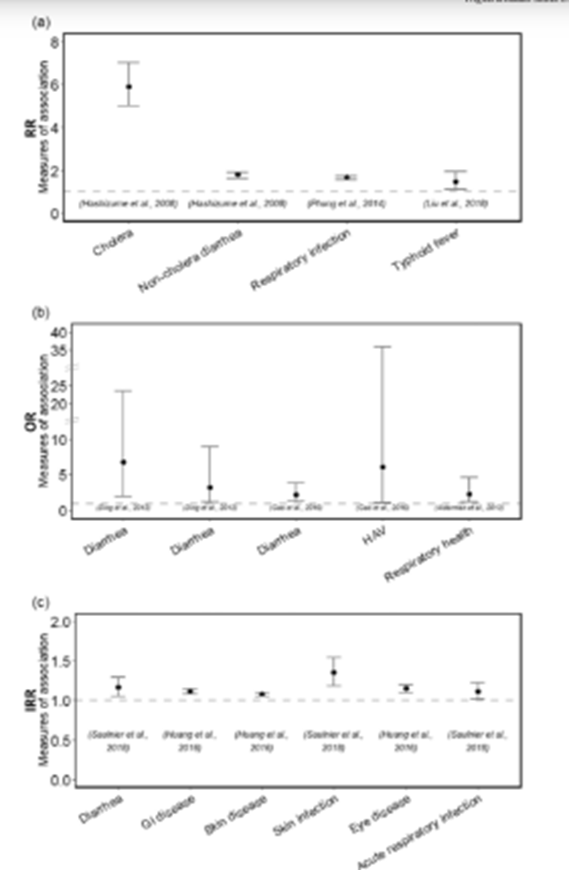

Fig. 7 shows the RRs, ORs, and IRRs of the association of different water-borne diseases and floods.

During the 1998 flood disaster in Bangladesh, there was a cholera outbreak (see “RR” section in Fig. 7) affecting 4 million people in Dhaka City. The risk of cholera was about six times higher in people exposed to the flood. Roads were submerged, making travel difficult, drainage and sewage systems were blocked, and water sources and tube-wells were contaminated by flooding water.

This near destruction of the sanitation system in Dhaka City led to increased transmission and therefore increased the incidence of cholera[4] [5].

Crowding in temporary shelters also became quite common.

This crowding, along with a compromised sanitation system, creates an ideal environment for the transmission of infectious pathogens- in this case, Vibrio cholerae was prevalent. Vibrio cholerae usually stays in human feces for 1–10 days, and transmission would be higher at shelters with high incidence[6] [7] [8].

After the 2007 flooding in Anhui province, China, the odds of diarrheal disease were increased 3.175 times compared to pre-flood conditions[9].

There were high risks of diarrhea at Fuyang, Bozhou, and Huai river regions[10] [11].

Generally, it is known that the average duration of floods is about 9.5 days during the year of 1985–2003[12]. However, the average days of flood exposure in the three regions mentioned above were about 17days, about twice longer than the usual time.

Extended flood periods increase the probability of the destruction of water and sanitation systems and the proliferation of disease-causing pathogens[13].

During the Huai river flood in China in June–July 2007, Hepatitis A virus- HAV infection was common.

The flood might destroy water treatment and conveying systems as well as storage tanks[14].

Also, the human body, which is humid and warm, is an appropriate place for HAV to multiply quickly.

Contaminated water and food, and inadequate health care systems were also factors increasing the transmission of diseases during and after the flood[15] [16] [17] [18].

Figure 7

Health Risks of Water-borne Diseases by Floods. (a) RRs, (b) ORs, and (C) IRRs with 95% confidence intervals

Vector-borne diseases.

Vector-borne diseases are infections of parasites, viruses, and bacteria that are transmitted by vectors like mosquitoes.

They constitute about 17% of all infectious diseases, and globally, 700,000 people die every year from diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, and other vector-borne diseases.

These examples are vector-borne diseases that often result from floods.

Countries in tropical and subtropical regions generally have a higher prevalence of those diseases[19] [20].

In the case studies, malaria and dengue fever were prevalent vector-borne diseases during and after floods.

During the floods in the Solomon Islands in 2014, 346 cases of dengue fever were recorded. After the 2005 floods in India, 81 out of 602 children had dengue fever[21] [22].

Physical health problems.

Injuries may occur during or post-flood, but they happen most often during relief work afterward.

During the 2013 floods in SouthernAlberta, Canada, emergency department data indicated an increase in the injury rate among Calgary residents[23].

In Lagos in 2011, women in the low-income region of Badia had a higher likelihood of being injured than women in higher-income areas[24].

Other studies do not mention injuries specifically but measure bodily pain, physical functioning, and other general health status indicators.

Physical functioning is usually described, sometimes through self-reporting, as reduced.

A study cited that after a flood in Bazhong City in China, the elderly had decreased scores of health-related quality of life and increased pain[25].

After surveying a population in Gangwon province, South Korea, before and after a flood, similar impacts were reported: decreased physical functioning and increased bodily pain[26].

Figure 5.

Continental distribution of the leading health impacts of floods and droughts according to 38 case studies.

[1] Huang L-Y, Wang Y-C, Wu C-C, Chen Y-C, Huang Y-L. Risk of flood-related diseases of eyes, Skin and Gastrointestinal Tract in Taiwan: A Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155166.

[2] Hunter PR. Climate change and water-borne and vector-borne disease. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;94:37–46.

[3] Andrade L, O’Dwyer J, O’Neill E, Hynds P. Surface water flooding, groundwater contamination, and enteric disease in developed countries: a scoping review of connections and consequences. Environ Pollut. 2018;236:540–9.

[4] RashidS. The urban poor in Dhaka City: their struggles and coping strategies during the f loods of 1998. Disasters. 2000;24:240–53.

[5] Hashizume M, Wagatsuma Y, Faruque ASG, Hayashi T, Hunter PR, Armstrong B, et al. Factors determining vulnerability to diarrhoea during and after severe floods in Bangladesh. J Water Health. 2008;6:323–32.

[6] Karim F, Sultan S, Chowdhury AMR. A visit to flood shelter in Dhaka City. Res Monogr Ser. 1999;15:40–5.

[7] World Health Organization (WHO) Cholera Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pntd.0003832 (accessed on Jul 10, 2019).

[8] Edition F, The I, Addendum F. WHO- Guidelines on drinking water quality- fourth edition; 2017 ISBN 9789241549950.

[9] Ding G, Zhang Y, Gao L, Ma W, Li X, Liu J, et al. Quantitative analysis of burden of infectious diarrhea associated with floods in northwest of Anhui Province, China: A Mixed-Method Evaluation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65112.

[10] Ding G, Zhang Y, Gao L, Ma W, Li X, Liu J, et al. Quantitative analysis of burden of infectious diarrhea associated with floods in northwest of Anhui Province, China: A Mixed-Method Evaluation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65112.

[11] Gao L, Zhang Y, Ding G, Liu Q, Jiang B. Identifying flood-related infectious diseases in Anhui Province, China: a spatial and temporal analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016; 94:741–9.

[12] Observatory DF. Interannual flood duration. Anal: Glob. Reg; 2019.

[13] Ding G, Zhang Y, Gao L, Ma W, Li X, Liu J, et al. Quantitative analysis of burden of infectious diarrhea associated with floods in northwest of Anhui Province, China: A Mixed-Method Evaluation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65112.

[14] Duclos P, Vidonne O, Beuf P, Perray P, Stoebner A. Flash flood disaster-nîmes, France, 1988. Eur J Epidemiol. 1991;7:365–71.

[15] McMichael AJ, Campbell-Lendrum DH, Organization, W.H, Corvalan CF, Ebi KL, Githeko A, et al. Climate change and human health: Risks and responses. World Health Organization; 2003 ISBN 978-92-4-156248-5.

[16] Watson JT, Gayer M, Connolly MA. Epidemics after natural disasters. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1–5.

[17] Campbell-Lendrum DH, Woodruff R, Prüss-Üstün A, Corvalán CF, Organization, W.H. Climate change: Quantifying the health impact at national and local levels. World Health Organization; 2007 ISBN 978-92-4-159567-4.

[18] Patrick ME, Christiansen LE, Wainø M, Ethelberg S, Madsen H, Wegener HC. Effects of climate on the incidence of campylobacter spp. in humans and prevalence in broiler f locks in Denmark. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:7474–80.

[19] WHO Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet. WHO 2019.

[20] World Health Organization (WHO) Vector-borne diseases Available online: https:// www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases (accessed on Jul 10, 2019).

[21] Natuzzi ES, Joshua C, Shortus M, Reubin R, Dalipanda T, Ferran K, et al. Defining population health vulnerability following an extreme weather event in an urban Pacific Island environment: Honiara, Solomon Islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:307–14.

[22] Zaki SA, Shanbag P. Clinical manifestations of dengue and leptospirosis in children in Mumbai: an observational study. Infection. 2010;38:285–91.

[23] Sahni V, Scott AN, Beliveau M, Varughese M, Dover DC, Talbot J. Public health surveillance response following the southern Alberta floods, 2013. Can J Public Heal. 2016; 107:e142–8.

[24] Ajibade I, McBean G, Bezner-Kerr R. Urban flooding in Lagos, Nigeria: patterns of vulnerability and resilience among women. Glob Environ Chang. 2013;23:1714–25.

[25] Adikari Y, Yoshitani J. Global trends in water-related disasters: An insight for policymakers; UNESDOC Digital Library; 2009 ISBN 978-92-3-104109-9.

[26] Heo J, Kim M-H, Koh S-B, Noh S, Park J-H, Ahn J-S, et al. A prospective study on changes in health status following flood disaster. Psychiatry Investig. 2008;5:186–92.