~25% of the population spend 5.4% of GDP in private health care, while ~75% of population spend only 3.9% of GDP on public health care (2017 data)

This is an abstract of the publication in below, focused on the title of this article, edited by the author of the blog. The purpose here is to provide a more Executive Language, to the excellent technical paper, intended to reach a wider audience, in order to influence change.

Edson Correia Araujo & Bernardo Dantas Pereira Coelho (2021) Measuring Financial Protection in Health in Brazil: Catastrophic and Poverty Impacts of Health Care Payments Using the Latest National Household Consumption Survey, Health Systems & Reform, 7:2, e1957537, DOI: 10.1080/23288604.2021.1957537,

Key messages:

The inequality among the public and the private system:

Total health expenditures (THE) in Brazil, estimated at 9.3% of the country gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017, is comparable to the average of countries within the OECD (8.8% of GDP),

- however, unlike most OECD countries, the private sector accounts for more than half of THE: representing 5.4% of GDP in 2017,

- while public spending accounted for 3.9% of GDP.7

- Household OOP (Out of Pocket) payments for drugs were estimated at approximately 1.5% of GDP in 2017, or 30% of all households’ health spending.7

The impact on the poor of catastrophic expenditure and impoverishment:

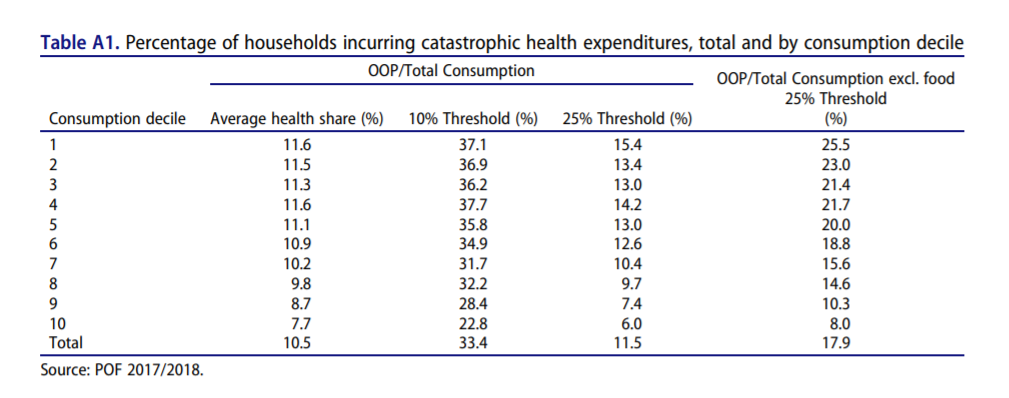

- A third of households spend more than 10% of their budget on health,

- and the share of households facing financial hardship is significantly higher among the Brazilian poor (37% among the bottom consumption deciles).

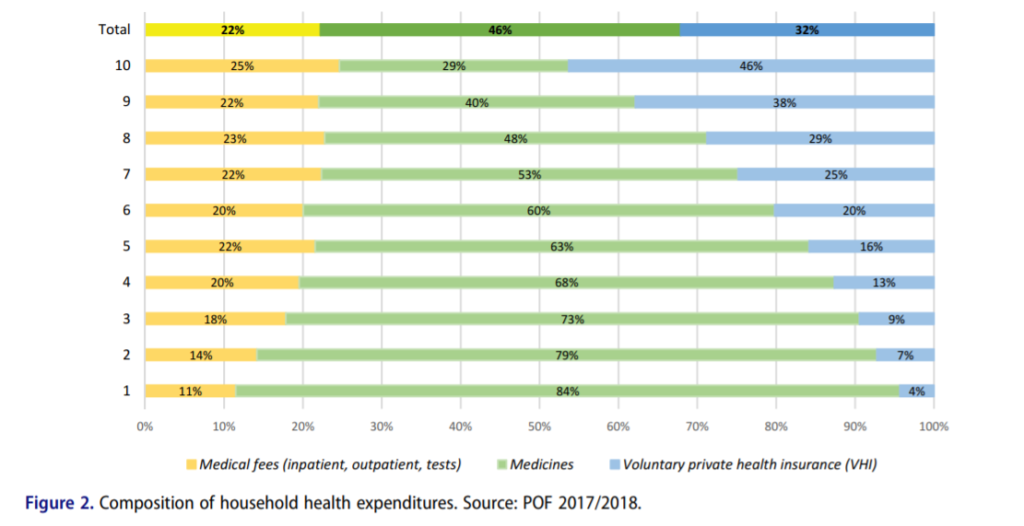

- Medicines are the main contributor to component of OOP health spending, reaching 85% of all OOP payments for the lowest consumption deciles.

- Households with women as household head and those with heads with more years of schooling have higher probability of incurring catastrophic health spending.

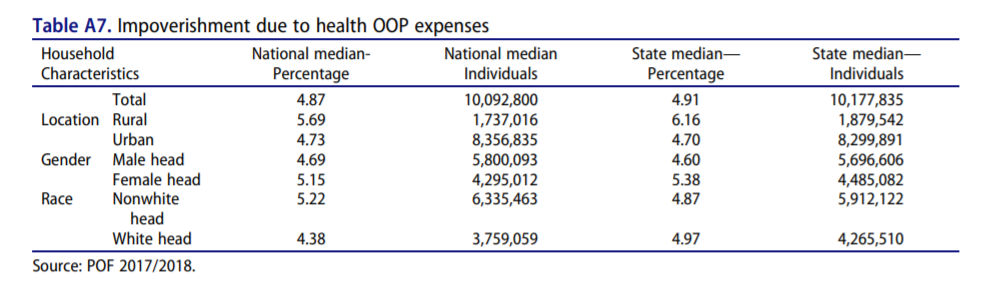

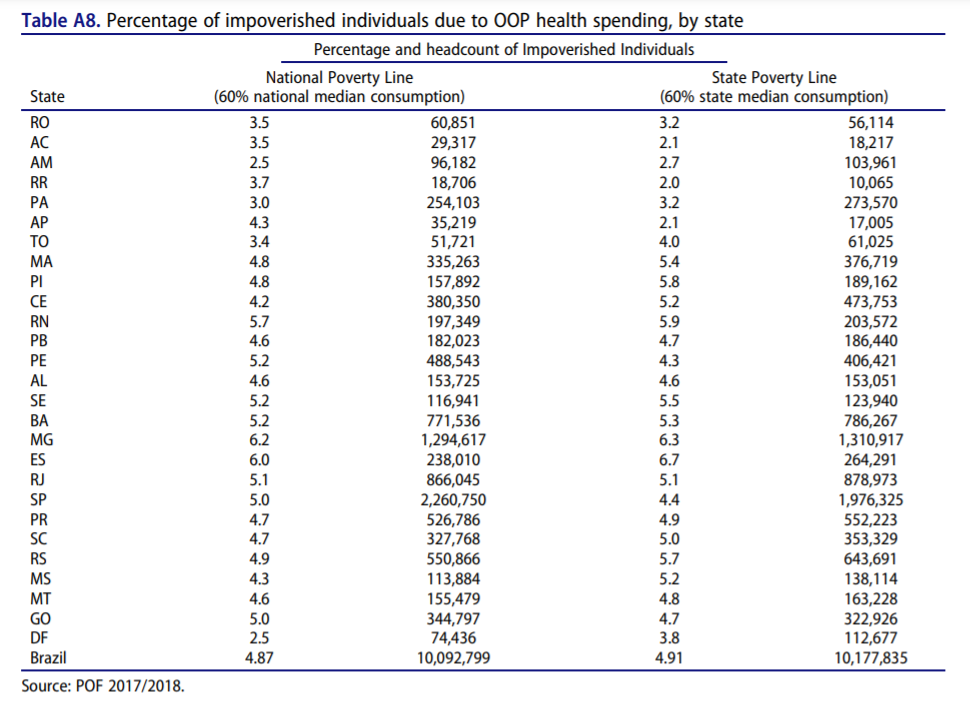

- Yearly, more than 10 million Brazilians are pushed into poverty due to OOP health care payments, which represents a larger percentage of individuals (4.87%) than reported globally (2.5%) or among Latin America and Caribbean countries (1.8%).

Conclusions & Recommendations

- Despite the achievements in implementing universal health coverage in Brazil, challenges remain to guarantee financial protection to its population (especially the Brazilian poor).

- Policies to expand access and affordability of essential medicines are key to improve financial protection in health in Brazil.

Introduction (extracted from the full version of the original publication)

Brazil was one of the first low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) to establish universal health coverage (UHC) with the creation of the Unified Health System ( Sistema Unico de Saúde or SUS) in the late 1980s.

The SUS, often referred to as the biggest public health care system in the world, covers virtually 100% of the Brazilian population (220 million people) and has over 50,000 treatment centers.

It is funded through general taxes and offers universal access to health care to the entire Brazilian population without cost at the point of delivery.

The creation of SUS has been associated with remarkable expansion of the public health service delivery system, improvements in access, and health outcomes.

- Between 1998 and 2019, the primary health care (PHC) teams increased from 4,000 to over 43,000 and enrollment in PHC surpassed 84 million people (from 10.6 million in the 1998).1

- Access to health services increased sharply, with the number of individuals seeking PHC services increasing by about 85% between 1998 and 2013.2,3

Despite the achievements, there are large gaps in the access to quality health services across socio-economic groups.

- The SUS, main source of care to two-thirds of the population, is often seeing as overcrowded, with long waiting times for specialized and elective services, while private sector providers offer services on demand often of higher perceived quality.

- Moreover, the cost of medication is a burden for poorer individuals, despite the support of programs such as the Farmácia Popular, which subsidizes the cost.4

- The differentials in access and quality of care push many households to incur out-of-pockets payments (OOP) or to purchase private voluntary health insurance (VHI), creating a segmented two-tier health system.

- Those who access care through OOP and/or VHI report easier access to preventive services and better quality of care then those relying solely on the SUS.5,6

As a result of the quality inequalities, health care financing in Brazil relies significantly on the private sector, both through PHI and OOP payments.

Total health expenditures (THE) in Brazil, estimated at 9.3% of the country gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017, is comparable to the average of countries within the OECD (8.8% of GDP),

- however, unlike most OECD countries, the private sector accounts for more than half of THE: representing 5.4% of GDP in 2017,

- while public spending accounted for 3.9% of GDP.7

- Household OOP payments for drugs were estimated at approximately 1.5% of GDP in 2017, or 30% of all households’ health spending.7

The expansion of the access to quality services remains a key challenge of the SUS.

The current Covid-19 pandemic shed light on several fragilities of the system, in particular the social and regional inequalities that are translated in the differences in mortality ratios.8

This paper focuses on how the system fragilities affect the financial protection of the population.

Financial protection means that everyone can have access to needed health services without incurring financial hardship.

Because OOP is subject to household’s ability to pay, without any type of risk pooling mechanism to protect households, it often results in socio-economic inequalities in the access to health services.9

Additionally, OOP may affect a household’s well-being by reducing the amount of household resources available to fulfill basic needs, such as food and shelter.

Catastrophic OOP health expenditure reduces non-health expenditure to a level where a household is unable to maintain consumption of necessities.

The effects of OOP payments on household well-being are measured by two main dimensions:

- catastrophic expenditures and

- impoverishment.

Catastrophic expenditure is defined by setting a threshold of proportional OOP spending of the household budget on health (which excludes VIH payments)a, if a household spends above that threshold it is said to face catastrophic health expenditure. Impoverishment due to health care spending measures the extent to which people are made poor, or poorer, after incurring health spending (which can be catastrophic or not).10

The latest global evidence shows that in 2015 nearly 927 million people faced catastrophic health expenditure and more than 180 million were pushed into poverty due to spending on health care.9

Catastrophic spending, measured as spending on OOP health exceeding 10% of household consumption, increased by 2.4% a year between 2010 and 2015 (from 9.4% of the population facing catastrophic expenditures in 2000 to 12.7% in 2015).

The WHO and the World Bank estimate that in 2015 OOP payments for health pushed approximately 99 million people into poverty (below $3.20 USD poverty line) and almost 90 million into extreme poverty (below $1.90 USD poverty line).9

Using the 2008 household expenditure survey, the report estimates at 25.6% the percentage of Brazilian households facing catastrophic health expenditure at 10% threshold (and 3.5% of households at a 25% threshold), and an increase in poverty of 1.98% of the population and extreme poverty of 1.04% of population ($1.90 and $3.20 USD poverty lines, respectively).

Globally, the main contributor to these outcomes are medicines and outpatient care.9,b

Discussion (excerpted from the original publication)

Brazilian households allocate, on average, 13% of their household consumption to health care.

Although this share is marginally larger among richer households (14% of the household consumption for those at the top consumption decile), it reverts when excluding VHI payments (which is mostly concentrated among the richer).

Purchase of medicines accounts for 46% all health care payments and 67% of all OOP payments for health and is particularly high among the Brazilian poor (reaching 84% of all health care payments for the lowest consumption decile).

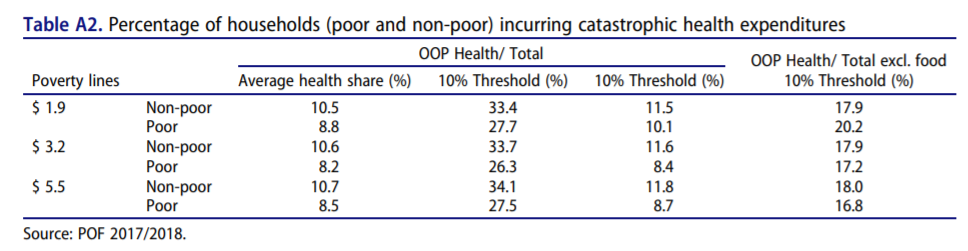

As a results, health care payments among poorer households in Brazil are mostly OOP payments and, consistent with the global evidence, these payments result in financial hardship for them-approximately 28% of the extreme poor households face catastrophic health care payments.

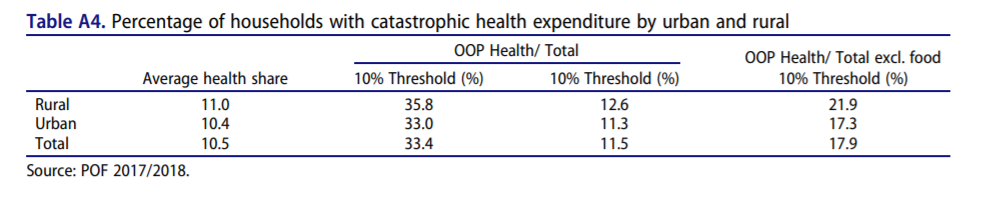

Overall, over a third of Brazilian households spend more than 10% of their budget on health, i.e., incurring catastrophic health spending. Catastrophic health spending is regressive, with poorer households (those at the bottom deciles of consumption distribution) bearing proportionally more the burden of these payments. In comparison with other countries Brazil presents a much higher incidence of catastrophic health expenditure.

The Global Monitoring Report shows a global average incidence of 12.7% using the 10% threshold and 2.9% using the 25% one.

Latin America has a higher average for the 10% threshold, with 15.1% incidence in 2015, the latest data, a decrease of 3.5% in comparison with data from 2010.

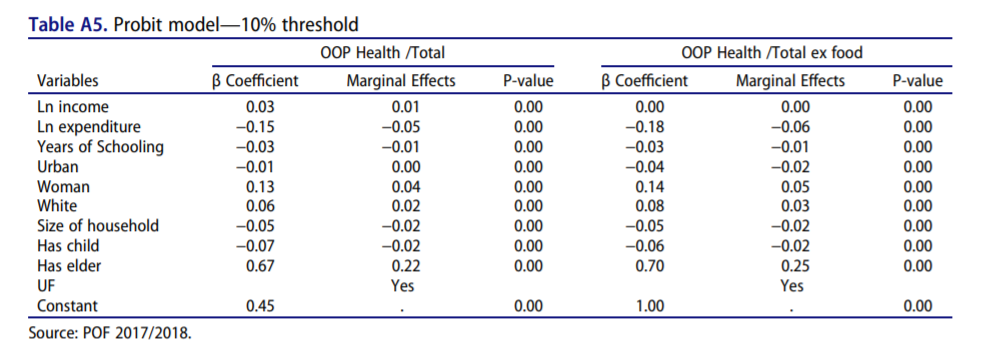

The analysis shows population groups that are most likely to face financial hardship due to health care payments.

- The richer the household, the less likely it will incur catastrophic health spending.

- Households with a woman as household head and those with heads with more years of schooling have higher probability of incurring catastrophic health spending.

- Contrary to the argument presented by O’Donnell et al.,19 larger households have lower probability of facing financial hardship due to OOP health care payments.

- Having elderly in the household is a major determinant for incurring catastrophic health spending, which may be linked to higher payments for medicines.

The results suggest an upward trend in the incidence of catastrophic health spending when compared to previous reports for Brazil.

Boing et al.,20 using the 10% threshold, showed an increase in the incidence of catastrophic health spending from 21.1% in 2002/2003 to 25% in 2008/2009 (using PF data for both periods).

Similarly, the Global Monitoring Report on Financial Protection in Health 2019, using 2008 POF data, estimated at 25.6% and 3.5% of households facing catastrophic health spending at the 10% and 25% thresholds, respectively.

Using a different database, the 1996 Living standards measurement studies, Xu et al.21 estimated that 10.27% of households in Brazil had catastrophic health expenditure levels, using a threshold of 40%. However, this study had a much smaller sample, with only 4,850 observations. Bernardes et al.11 use a different database, the Estudo Longitudinal de Saúde dos Idosos Brasileiros (ELSI-Brasil) of 2015–2016, a survey with a sample of 9,412 individuals living in households that have at least one individual over the age of 50.

They estimate that 17.9% of the households spend over 10% of their budget in health expenses, while 7.5% spend over 25%.

A similar upward trend is observed in terms of percentage of households pushed into poverty due to health care payments, 2.62% according to the Global Monitoring Report and 4.87% (or 10 million Brazilians)f. Kawabata et al.22 discuss the potential impoverishment of health expenditure, and in particular how despite a country adopting universal coverage policy, catastrophic health expenditure may continue leading to impoverishment if the benefit package of social security is too small.

Brazil is performing worse in terms of financial protection in health than the global average and among the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) countries.

The latest evidence points to a global average of 12.7% of households facing catastrophic health spending, and among LAC countries this share reaches 15.1% (using a 10% threshold).

Likewise, globally 2.5% of the population is pushed into poverty due health care payments (1.8% of LAC households), which represents 183.2 million people globally (11.5 million of them in the LAC region)-2015 estimates using 60% of median daily per capita household consumption.

Brazil is performing worse in terms of financial protection in health than the global average and among the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) countries.

In terms of policy, our results suggest that Universal Health Coverage does guarantee that poor households are safe from having catastrophic health expenditure, as expenditure for medication alone is sufficient for poor households to compromise a large percentage of its budget.

This conclusion goes in line with Luiza et al.4 in which medication expenditure was responsible for 60% of the households identified as having catastrophic expenditure.

Conclusion (excerpted from the original publication)

This article presents new evidence on financial protection in health in Brazil.

It shows that despite the achievements over the last 30 years, the Brazilian health system still faces challenges to guarantee financial protection to all Brazilians, particularly the poor.

This is particularly important given the fact Brazil has a universal health system which provides services entirely free at point of use for all Brazilians.

Moreover, the trend in catastrophic health spending and impoverishment due OOP health care payments is upward over the same period that the SUS has been consolidated as the main option to access health services among the Brazilian poor.

Although quality differentials and timeliness to access health services differ widely (across public and private sectors) in the two-tier Brazilian health system, these do not explain the financial hardship faced by households (particularly the poor).

Consistent with the global evidence, medicines are the main component of OOP spending on health in Brazil and, consequently, a main determinant for whether a household faces financial hardship (incurring catastrophic health spending or pushed into poverty due OOP health care spending).

This article presents new evidence on financial protection in Brazil. In addition to contributions to the debate on SUS financing, the analysis contributes to the global debate on UHC as Brazil has one of the largest public health systems in the world, SUS, and was one of the first low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) to achieve UHC.

APPENDIX

References

See the original publication

Originally published at https://www.tandfonline.com.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

About the authors & Affiliations — Original Publication

Edson Correia Araujo

Bernardo Dantas Pereira Coelho

Health, Nutrition and Population Global Practice, The World Bank, Washington, DC, USA