The Economist

Catherine Brahic, Environment editor

November 8, 2021

The fact that decisions within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, whose parties are assembled in Glasgow for COP26, are made by consensus is often blamed for the glacial pace of climate negotiations.

Obtaining undivided agreement from 197 parties, each of which comes to the table with its own national needs and priorities, is never going to be easy.

In fact, no formal rule says decisions must be unanimous. Voting procedures have been a point of disagreement since the earliest COP summits in the 1990s, when a small group of oil-producing countries opposed the idea of a decisive three-quarters majority. Consensus became the default, though there is no text requiring it.

Its straight-jacket has been wriggled out of a few times, most notably in 2015, when the Paris agreement was adopted.

After two weeks of exhausting negotiations and years of preparation, delegates finally had a text that nearly everyone could agree to.

Nicaragua, famously, resisted. Its representative, Paul Oquist, believed that because the Paris text relied on governments making voluntary cuts to their emissions, it would not be enough to prevent 3°C of global warming (you can read here why he may have been right).

Nevertheless, Laurent Fabius, France’s foreign minister and president of the proceedings, ploughed on. Shortly before 7.30pm on Saturday December 14th, he declared in one breath and with barely a glance over his glasses:

“I am looking at the room, I see the reaction is positive, I hear no objections, the Paris climate agreement is accepted.” Only after he had brought down his gavel did he register Mr Oquist’s objection.

Britain, as host of this year’s summit, has found its own path around the restrictions of consensus.

The first week of COP26 produced a flurry of multilateral announcements, deals, pacts and agreements, most notably on finance, forests and methane emissions.

In every case some big countries were involved, thus giving the impression that COP26 was getting many things done. But in every case some big countries were missing.

Such is the double-edged nature of multilateral agreements struck outside the formal UNFCCC process: more deals-for cash, for forests, against coal, against methane-but with fewer countries party to them.

Significant progress requires the agreement of all relevant countries, and on this front COP26 has been a decidedly mixed bag.

The core UN event will take centre-stage this week.

Attention will focus on the pieces of the puzzle that, by custom if not rule, demand full consensus: guiding principles for a UN-sanctioned global carbon market, if it is to exist, and for a global emissions stocktake exercise which begins next year and will assess progress towards the Paris agreement’s goals.

Many want signatories to ratchet up their climate pledges annually rather than every five years, in order to accelerate global decarbonisation over the coming decade.

Some say that without this, cumulative historical emissions will be too large to limit global warming to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels.

Rich countries must find a way to reassure poor ones that they will deliver on their promise to mobilise $100bn every year to help them decarbonise and adapt to climate change, and they must make up for the fact that they already missed a 2020 deadline for doing this.

The contentious issue of loss-and-damage-often portrayed as compensation to be paid by rich countries to poorer ones for the damage they are already incurring due to extreme weather-is another open wound.

Developing ones would like to see it become the guiding principle for new flows of finance.

And then there is the overarching question of how far government promises still have to go in order to truly set the world on a course that looks likely to avoid more than 2°C of global warming.

Fresh modelling analysis is expected on Tuesday. But the picture so far is not reassuring.

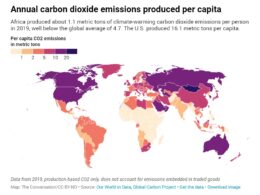

The latest results of the global carbon budget, an analysis of sources and sinks produced annually by a large consortium of academics, shows that emissions will return to pre-pandemic levels in 2021 and emissions from coal and gas are both now above where they were before covid-19 struck.

The COP26 “deals”, be they fringe coalitions of the willing or globally agreed with consensus from all, still have a long way to go.

Originally published at https://view.e.economist.com.