Commonwealth Fund

Caroline Pearson, Heather Britt, and Lindsey Schapiro

SEPTEMBER 21, 2021

Abstract

Issue:

- When COVID-19 began to spread, countries scrambled to implement sweeping responses across their public health and health care delivery systems.

- Lack of preparation often meant international leaders were slow to identify and respond to the crisis, and many health care delivery systems were overwhelmed — short on critical infrastructure, supplies, and staff.

- Beyond the initial challenges posed by the pandemic, its prolonged duration has strained health care facilities and providers.

Goals:

- Provide specific examples of how international delivery systems adapted to respond to the pandemic and identify lessons learned that can be applied to U.S. health care delivery and public policy.

Methods:

- NORC conducted a literature review and in-depth interviews of health system and government leaders in five countries: Australia, Finland, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea.

- An advisory board of U.S. experts informed research areas and identified opportunities for the United States.

Key Findings:

- Policies and actions that address staffing, access to care, decision-making, data infrastructure, and communication can help countries prepare for a pandemic, respond quickly, and sustain the response for the duration of the public health threat.

Conclusion:

- As COVID-19 cases rise once again, planning and investment can help the United States confront future health crises.

People wearing facial masks as a preventive measure against the spread of COVID-19 cross the road in Seoul, South Korea, on August 6, 2021.

South Korea crafted national preparedness plans based on lessons learned from past pandemics to facilitate a quick and sustained response to the virus.

Photo: Simon Shin/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Introduction

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the U.S. health care delivery system — including hospitals and other facilities, health care workers, payers, and policymakers — has been facing unprecedented challenges. At different points during the pandemic, the virus has strained hospital capacity, disrupted supply chains, and delayed regular ongoing care and elective services, deeply affecting health systems’ finances. COVID-19 also has exacted a heavy toll — mental, emotional, physical, and financial — on the health care workforce.

This issue brief explores how five diverse countries — Australia, Finland, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea — with advanced health care delivery systems have adapted and innovated to meet the challenges of operating during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the goal of identifying lessons for care delivery in the United States. The political structures of these countries vary, but like the U.S., Australia and Germany both have large federated systems in which national and regional or state governments share responsibility.

An advisory board of nine U.S. health care experts representing hospital administrators, physicians, and nurses from various health systems convened first to prioritize research topics and then again to assess which of the international approaches would be the most feasible and have the greatest impact in the U.S. (See “How We Conducted This Study” for further detail.)

Exhibit 1 provides an overview of the countries studied.

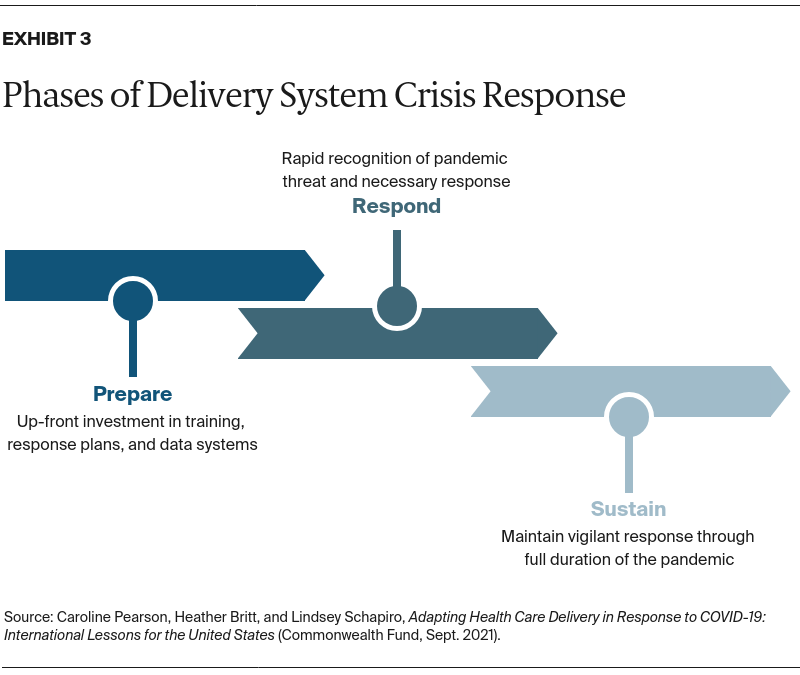

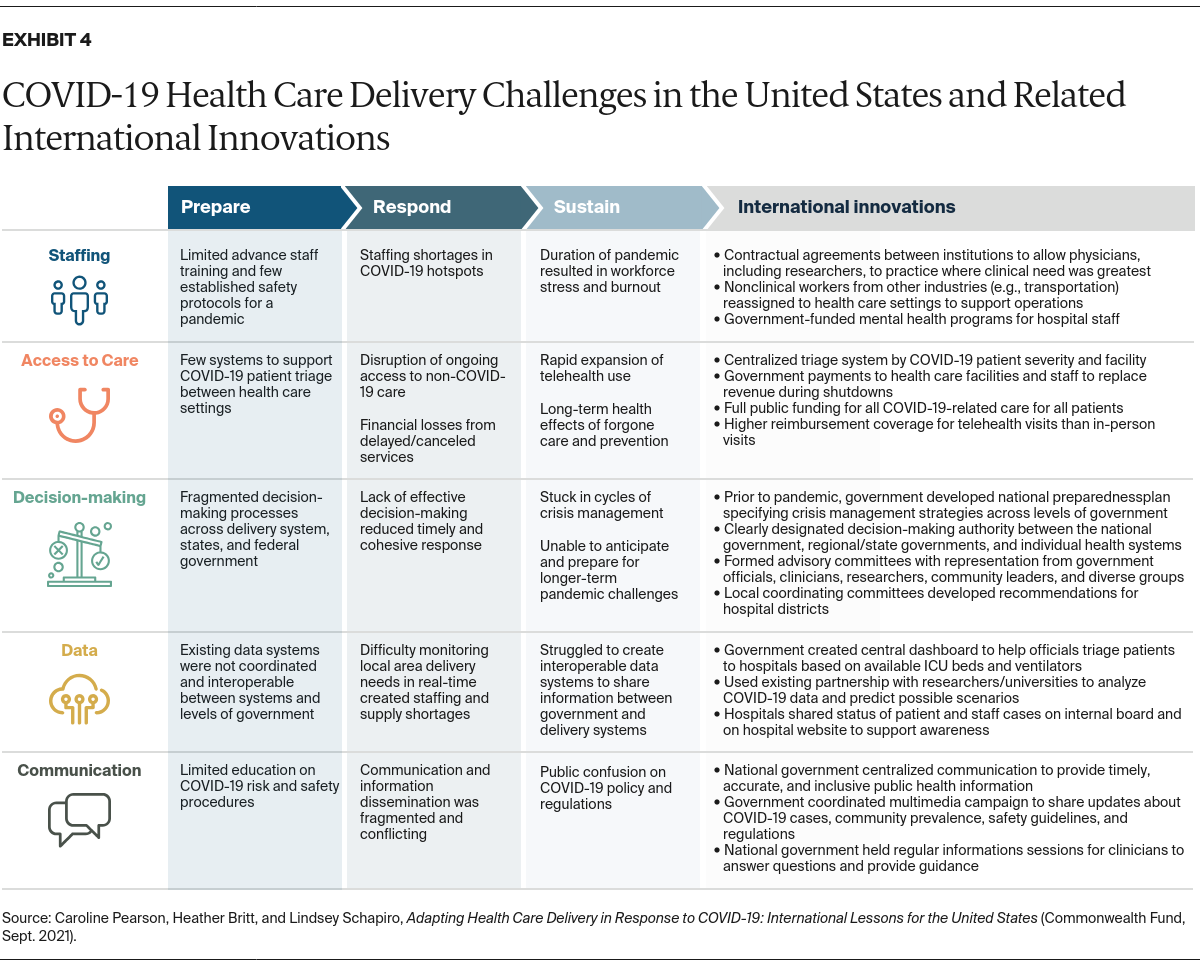

The advisory board identified five critical areas for research — staffing, access to care, decision-making, data, and communication — based on the COVID-19 challenges experienced by the U.S. health care delivery system (Exhibit 2). These areas provided the framework for data collection and analysis.

While each of these areas was critical to success, the experience of health systems also was affected greatly by factors largely outside of providers’ control.

Public health measures, policy actions, payment reforms, culture, and politics all had outsize influence on providers’ ability to operate effectively during the pandemic. For instance, countries that implemented strong infection control policies early in the pandemic achieved lower case and death rates, which dramatically reduced the burden on their health care delivery systems.

I think there’s a lot of focus on the health care system responses, but the countries that have done the best, it’s their public health response.

Singapore public health expert

Findings from International Experience

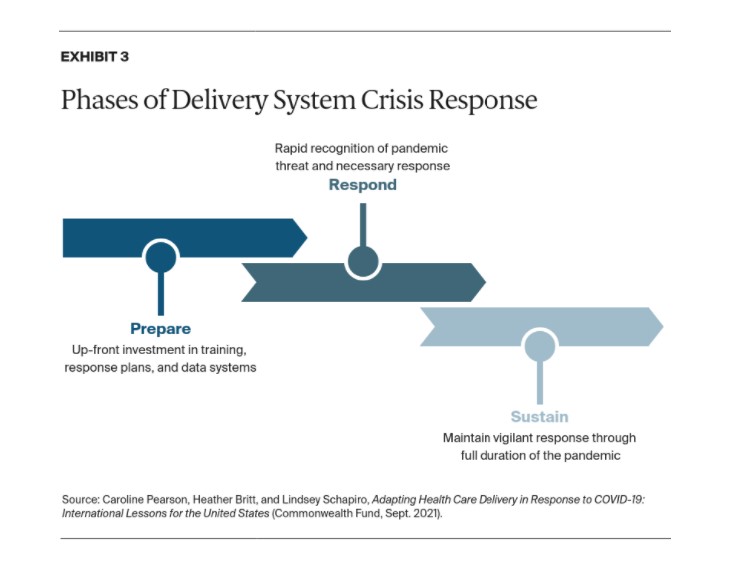

Lessons from innovations abroad may help the United States plan for future public health emergencies by improving preparedness, responsiveness, and sustainability (Exhibit 3). When a threat is first identified, countries that act quickly to manage their pandemic response can help protect their health care delivery systems and patients. Investing in delivery system resilience also can help sustain a successful response throughout the duration of a pandemic.

PREPARE: Experience and preparation enabled some countries to respond quickly and maintain health care delivery throughout the public health emergency.

Our research showed that countries that have recent or prior experience with public health and safety crises were better prepared to identify the COVID-19 threat and implement delivery system responses quickly. For example, Singapore and South Korea, which had recent experiences with epidemic viral respiratory illnesses, crafted preparedness plans that included regular pandemic training and drills, patient triage protocols, and decision-making procedures. Singapore recently invested in pandemic infrastructure, including a 500-bed infectious disease hospital designed to ensure the safety of patients, staff, and the community during an outbreak. In Australia, experts credit the country’s rapid pandemic response, in part, to its recent national wildfire emergencies.

Quick action in these countries at the first signs of an outbreak helped prevent the rapid rise in cases that overwhelmed many other countries’ health care delivery systems. Without this burden on hospitals and health care workers, these countries were better able to sustain their COVID-19 response for the long term.

RESPOND: Countries rapidly implemented pandemic response structures.

Nimble health care systems responded quickly to early signs of the pandemic, including standing up teams and systems to provide data to decision-makers and public health communicators.

- Adaptive management approaches to speed decision-making in uncertainty

- Sharing information between government and health care decision-makers.

- Consistent communication about health care guidelines.

- Responding to surges while providing routine care.

- Mitigating staffing shortages.

Adaptive management approaches to speed decision-making in uncertainty. During any crisis, decision-makers must respond to a dynamic enviornment with limited information. In the COVID-19 pandemic, leaders often found that decision-making authority was unclear between levels of government, health system administrators, and frontline providers. Across countries, health systems worked to shorten and clarify decision-making cycles by meeting more frequently, developing new decision-making processes, and clearly distributing and specifying decision-making authority between stakeholders. For example, Singapore activated a national COVID-19 task force to coordinate information and logistics across ministries, and public and private organizations. This cross-functional COVID-19 response team encouraged rapid decision-making and clarified decision-making responsibility.

Sharing information between government and health care decision-makers. Timely, centralized data was a hallmark of effective responses to COVID-19. Countries with national electronic medical records and standard, national reporting requirements could more easily create dashboards to monitor health system capacity (e.g., intensive care unit beds) and redeploy patients, supplies, and staff. Australia and Singapore both developed a dashboard compiling real-time epidemiology and health care supply procurement data to inform decisions made by the prime minister and secretary of health. Singapore also developed a centralized capacity dashboard to triage patients between facilities and direct supplies. South Korea had hospital-specific dashboards to inform employees about the number of COVID-infected patients in the hospital and how many health care staff were in quarantine.

We have the [national] Department of Health website as the single source of truth. And this is where all our communications have been posted.

Australian Department of Health official

Consistent communication about health care guidelines. Countries around the world worked to streamline their government and public health messaging about COVID-19. Australia, Finland, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea all used a national communications approach, often with a single, designated source of truth. Countries had daily or weekly broadcasts with the heads of state (Australia, Finland, Germany), national briefings from scientists (Australia, Finland), and federally funded mass media communication (Finland, Singapore).

Australia focused particularly on communicating to hard-to-reach populations and amplified messaging through medical professionals. Australia also held regular information sessions for clinicians to answer questions and provide consistent guidance. Singapore published daily updates in the national newspaper and included cartoons in multiple languages to explain the unfolding situation and corresponding guidelines. In these countries, consistent and clear messaging reduced confusion and improved awareness among the public and medical professionals.

Responding to surges while providing routine care. All countries worked to maintain access to care during COVID-19. Countries increased capacity by setting up temporary facilities (Australia, Germany, Singapore, South Korea), converting primary and elective care clinics into respiratory clinics (Australia), and keeping stable patients at home (Australia). Singapore triaged COVID-infected patients to designated facilities based on severity to isolate infected patients and reduce the strain on hospitals. Mild or asymptomatic patients went to field hospitals where they were monitored. Patients with comorbidities who were at risk of needing more intensive care were sent to hospitals. By doing this, Singapore sought to limit exposure within households and reduce strain on acute care settings.

Virtual care was limited prior to the pandemic in all countries studied but was quickly leveraged both to keep non-COVID-19 patients out of health care facilities and to reach rural and underserved patients. South Korea temporarily allowed telemedicine for non-COVID outpatient use and even incentivized its use with higher reimbursement than in-person visits. Singapore provided remote monitoring via wearable technology to asymptomatic COVID-19 patients in field hospitals as a way to monitor symptoms without overburdening the health system.

Mitigating staffing shortages. In Australia, Finland, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea, health care institutions mitigated or prevented staff shortages by recruiting more health care workers (including students, retirees, volunteers, and foreign health care workers), redeploying staff across institutions, and training staff for new roles. Some governments and employers provided financial incentives (Finland, Germany) and additional support to staff, like paying for hotel rooms to avoid exposing health care workers’ families (Singapore). In countries where the pandemic increased in severity, some staff were asked to work longer hours, were not allowed to take leave, and were shifted to new clinical units/roles with additional training.

SUSTAIN: Countries endured a long-term disruption to their health systems.

A quick response was not enough to ensure health care system effectiveness throughout the pandemic. Health care systems have been required to sustain an effective response for more than a year. To weather a long pandemic, resilient systems focused internally, for example, on staff wellness, and externally, such as on strong coordination with government and other partners (Exhibit 4).

- Preventing and reducing health care worker burnout with mental health support.

- Collaborating between sectors and services.

- Coordinating roles for federal and state government.

Preventing and reducing health care worker burnout with mental health support. Aware of the mental health impact on health care staff, Australia, Finland, Germany, and Singapore developed resources to support staff such as call lines, online treatment, and psychological first aid. One expert noted that the best way to address mental health strain on health care workers was to prevent overburdening their hospitals.

Collaborating between sectors and services. Public and private partnerships allowed health institutions to leverage additional resources to prevent and mitigate strains on the system. Singapore relied on public and private coordination to stand up field hospitals and deploy additional staff when there were shortages of personnel and facilities, while Australia and Germany developed contractual arrangements allowing providers to work legally in both private and public sectors. Most notably, Singapore recognized the largely untapped private sector and university resources for pandemic data and analytic needs.

Coordinating roles for federal and state government. Countries relied on data sharing across the country and regularly communicated about capacity, workforce, logistics, and infrastructure issues. Australia, Finland, and Germany worked with state health departments to ensure a coordinated response. Many countries cited instances of confusion around local versus federal roles and breakdowns in decision-making, which created inefficiency for health systems and patients. To prevent and reduce confusion around federal versus local roles, leaders worked hard to create clarity, sometimes relying on national leadership delegation (Finland) and other times deferring directly to state leadership (Germany). In Germany, state officials reconvened every few weeks to discuss measures currently in place and to reassess the situation. National governments in Australia, Germany, and Singapore required states and territories to share ICU capacity information in real time to track the pandemic across the country.

Recommendations for Effective Future Response

International experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate that strong preparation facilitates a more immediate and effective response to a threat and enables the delivery system to sustain that response. Preparation includes scenario planning, developing infrastructure, conducting training and simulation exercises, and establishing durable funding mechanisms. Addressing the gaps that challenged our ability to effectively provide care throughout the pandemic will help the United States prepare for future public health crises, whatever form they may take.

While international lessons offer inspiration for the U.S., the specific policies and implementation approach must be adapted to reflect America’s unique federalist environment. Since 2006, the U.S. federal government has supplied pandemic funding to health systems, states, and local governments via the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act. Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Congress authorized additional COVID-related emergency stimulus funding to support individuals and families. However, state governments and private health systems remain primarily responsible for planning and executing emergency responses. The varied responses of governors, local health officials, and hospitals have greatly impacted the U.S. COVID-19 experience across regions.

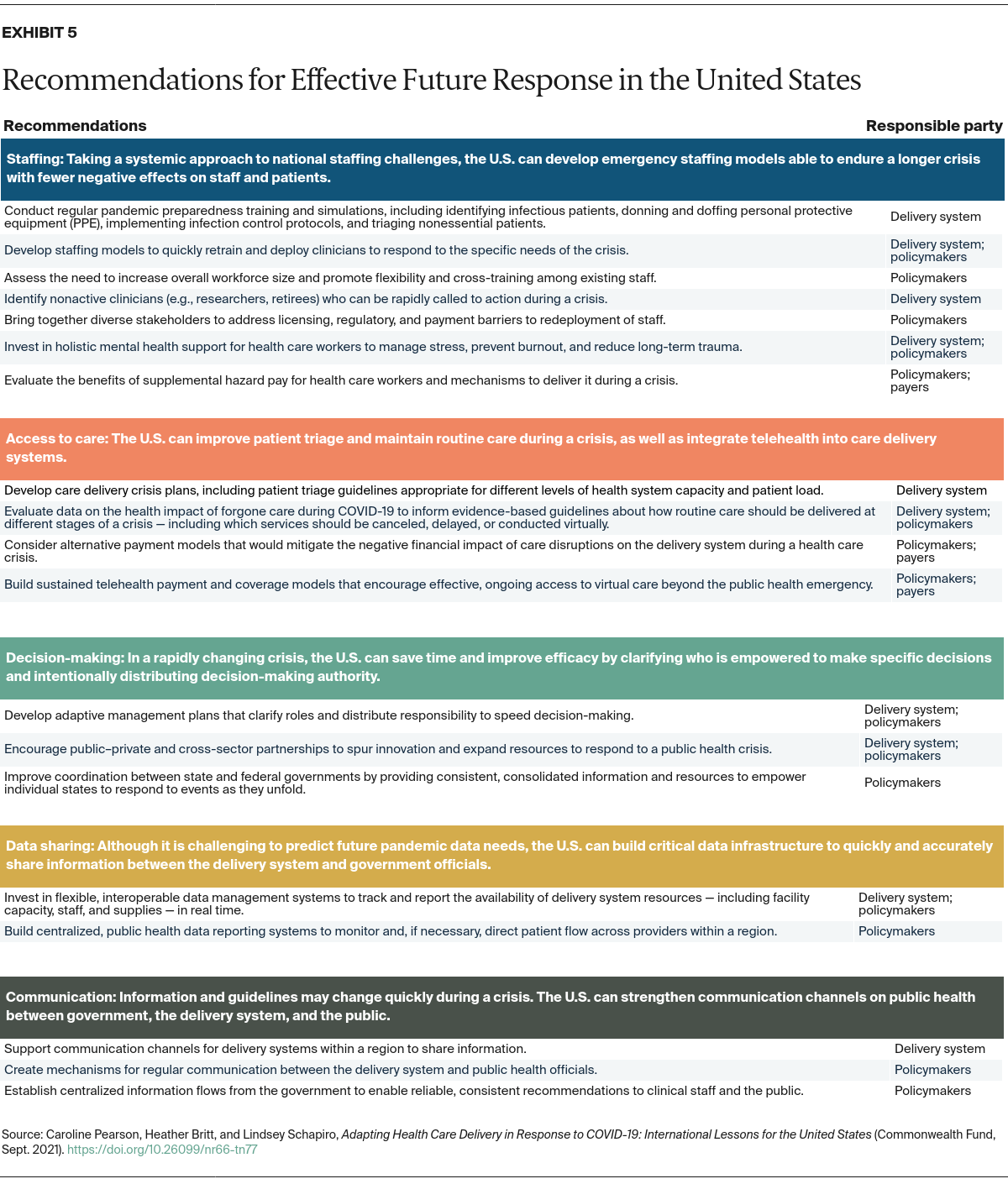

Following are two broad recommendations for the U.S., based on the pandemic response of other countries.

- Invest in delivery system resilience to support health care workers and maintain access to care.

- Develop preparedness plans to guide decision-making, data sharing, and communication.

Invest in delivery system resilience to support health care workers and maintain access to care.

Nearly half of U.S. health care workers reported that their pandemic workload was a major stressor, according to a survey by Mental Health America. Insufficient staffing increases staff burnout and attrition rates, further stressing the remaining staff in a vicious cycle. This may lead to workforce shortages across health care facilities. As pandemic conditions stretch into multiple years, the system needs sophisticated approaches to continue delivering routine care in a safe and efficient manner. Sustaining a long-term pandemic response will require sufficient staffing to avoid overload, workforce support to mitigate stress, and ongoing access to care for the population.

Develop preparedness plans to guide decision-making, data sharing, and communication.

Plans should guide and clarify staffing, care delivery, decision-making roles, data sources, and communication channels for health systems, governments, and the private sector. Plans also need to be flexible enough to adapt to the specifics of any new health care crisis. Because preparedness plans are useless on the shelf, resources should be widely available to allow for a rapid application of those protocols.

Specific recommendations are detailed in Exhibit 5.

Call to Action

Currently, rising vaccination rates have begun to alleviate pressure on some delivery systems, but new variants of the virus threaten progress in the United States and around the world. While the health care delivery system in the U.S. has begun to address some of these recommendations, there is much more to do in the battle against COVID-19 and to prepare for our next public health crisis. Focusing on planning and investment to meet future public health crises can help the U.S. prepare for a wide range of threats. Taking action also can improve the country’s ability to respond rapidly during a public health emergency and sustain an efficient health system response for the duration of the crisis.

Highlights by Country

SINGAPORE

After SARS, Singapore conducted pandemic simulations annually. Scheduled randomly, they involved actors that would present with signs of infection after travel.

The simulations involve all workers in the hospital — from nurses and doctors to receptionists — and train them to identify, triage, and isolate contagious patients who present at the hospital.

AUSTRALIA

The National COVID-19 Health and Research Advisory Committee was established in Australia in April 2020 to convene community leaders, parliamentarians, clinicians, researchers, and representatives of diverse groups. The task force required advanced data linkage, analysis, and visualization, so the government conducted an internal audit to identify staff with these skills and reassigned them to the COVID-19 response team.

The federal government also centralized communication to provide timely, accurate, and inclusive public health information. Federal health ministers held regular webinars for clinicians to provide updated guidance and answer questions.

GERMANY

German hospitals executed new contract agreements with research institutes to enable physician-researchers to staff hospitals during surges.

Hospitals negotiated redeployment contracts with the institutes, allowing reassignment without interrupting regular employment contracts and allowing hospitals to reimburse institutes for actual staff hours.

SINGAPORE

Singapore redeployed staff from sectors heavily impacted by the pandemic (e.g., tourism) to health care delivery:

- Flight attendants and hospitality workers were sent to work in hospitals in a nonmedical capacity.

- Hotels were turned into isolation centers when people entered or reentered the country.

- Bus drivers were recruited to pick up travelers from the airport and bring them to isolation centers.

FINLAND

In Finland, local coordination committees made up of regional experts and decision-makers — mayors, central government representatives, public health officials, and teaching professionals — developed restriction recommendations for each hospital district.

HOW WE CONDUCTED THIS STUDY

Researchers at NORC conducted a literature scan to understand how global health care delivery systems successfully navigated challenges to provide care and contain virulent spread during the COVID-19 pandemic. An advisory board of nine U.S. health care delivery system experts helped identify priority research topics and select countries for in-depth study.

The research team selected five countries (Australia, Finland, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea) and analyzed their COVID-19 response, as well as their health system structure, payment system, and public health infrastructure. NORC reviewed literature and conducted 23 interviews with experts to collect examples of effective health care delivery practice and identified more than 250 innovations implemented in those countries’ delivery systems.

At a second meeting, the advisory board provided feedback on preliminary findings and helped to prioritize innovative approaches most likely to be feasible and impactful in the U.S. context.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

At NORC, Jessica Kerr, manager, Vaiddehi Bansal, M.S., senior research analyst, and Shalanda Henderson, senior research analyst, contributed to the research and writing of this issue brief; Roy Ahn, Ph.D., M.P.H., and Prashila Dullabh, M.D., acted as senior advisors throughout the research.

The authors would like to thank Reginald D. Williams II, Katharine Fields, Molly FitzGerald, and Roosa Tikkanen of the Commonwealth Fund for support of this project. We also extend heartfelt appreciation to all interview participants who carved out time from their critical pandemic response roles to contribute to this study. We appreciate the insights and guidance from members of the U.S. advisory board:

- Katie Boston-Leary, Ph.D., M.B.A., M.H.A., R.N., NEA-BC, director of Nursing Programs, Nursing Practice, and Work Environment, American Nurses Association

- Liz Goodman, J.D., M.S.W., Dr.P.H., executive vice president, Government Affairs and Innovation, America’s Health Insurance Plans

- Yalda Jabbarpour, M.D., medical director, Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies, and family physician

- June-Ho Kim, M.D., M.P.H., faculty member of the Primary Health Care Program at Ariadne Labs, instructor in Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an attending physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in the Division of General Medicine and Primary Care

- Clare Rock, M.D., assistant professor of medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and associate hospital epidemiologist

- Meena Seshamani, M.D., Ph.D., former vice president, Clinical Care Transformation, MedStar Health (currently director of the Center for Medicare at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services)

- Lisa Stand, J.D., senior policy advisor, Policy and Government Affairs, American Nurses Association

- Krishna Udayakumar, M.D., M.B.A., director of the Duke Global Health Innovation Center, and faculty of the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy

- Scott Young, M.D., executive director and senior medical director, Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute, and associate executive medical director, the Permanente Federation

CITATION

Caroline Pearson, Heather Britt, and Lindsey Schapiro, Adapting Health Care Delivery in Response to COVID-19: International Lessons for the United States (Commonwealth Fund, Sept. 2021). https://doi.org/10.26099/nr66-tn77

Originally published at https://www.commonwealthfund.org on September 21, 2021.