European Observatory — on Health Systems and Policies

Ewout van Ginneken; Sarah Reed; Luigi Siciliani; Astrid Eriksen; Laura Schlepper; Florian Tille; Tomas Zapata

Editor: Ewout van Ginneken

July 2022

One page summary by:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

The Health Strategist — research and advisory institute

Pandemics Response Unit

July 14, 2022

- Our health systems continue to face the dual challenge of managing both COVID-19 cases and disruption to non-COVID-19 health services, which has led to growing backlogs and waiting lists since the beginning of the pandemic.

- In order to restore services to pre-pandemic levels and catch up on care, we need to understand and act on what we have learned from the pandemic, including

– investing in the health workforce,

– increasing funding for the health infrastructure of the future, and

– maintaining the innovative forms of service delivery that proved useful in reaching out to key groups affected by the pandemic.

In this process, it is important that policies that further rationalize health care delivery (including by reducing waste and inappropriate care, and making increased use of digital solutions), do not increase inequalities in utilization and health.

Pre-pandemic waiting times and missed care during the pandemic mean that restoring care to previous levels will not be enough to overcome the backlogs.

To clear the backlogs), health systems have employed three broad strategies:

- Increasing the supply of workforce and staffing

- Improving productivity, capacity management and demand management

- Investing in capital, infrastructure and new community-based models of care (including partnerships with the private sector)

Clearing care backlogs as quickly as possible will be critical for maintaining health gains achieved before the pandemic and avoiding increasing excess mortality.

SELECTED IMAGES (INFOGRAPHIC)

Foreword

For more than two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has stretched health systems, restricting their ability to provide care for all people when needed.

The simple truth is that, while countries in our Region have some of the strongest health systems in the world, none was fully prepared or resilient enough to really tackle the wide-ranging impacts this emergency has brought.

One major concern since the onset of the pandemic has been the extent to which countries’ capacity to maintain essential health services has been negatively affected.

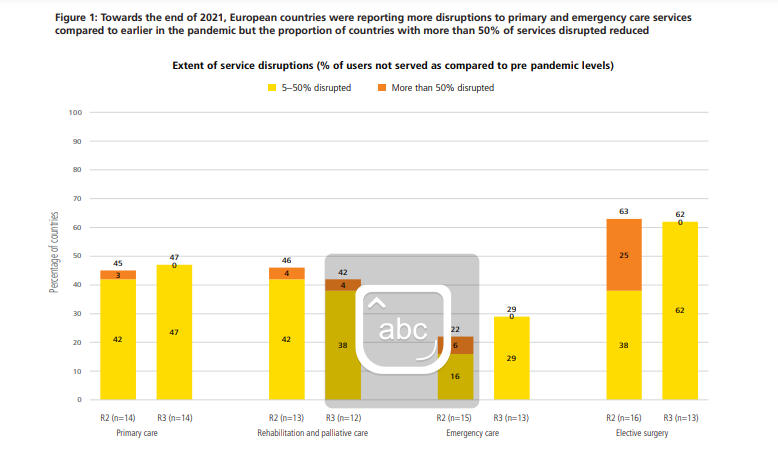

In 2020, over 90% of countries in the WHO European Region reported some disruption to essential health services. At the end of 2021, a 23-country survey indicated similarly high levels of disruption.

This underlines that our health systems continue to face the dual challenge of managing both COVID-19 cases and disruption to non-COVID-19 health services, which has led to growing backlogs and waiting lists since the beginning of the pandemic.

For each person who cannot receive care when they need it, this delay may have severe consequences, ranging from worsening health problems and prolonging recovery to decreasing quality of life.

In order to restore services to pre-pandemic levels and catch up on care, we need to understand and act on what we have learned from the pandemic, including investing in the health workforce, increasing funding for the health infrastructure of the future, and maintaining the innovative forms of service delivery that proved useful in reaching out to key groups affected by the pandemic.

This brief is a valuable resource for policy-makers seeking to understand the extent of disruption to health services caused by COVID-19, the reasons behind this, and what different countries are doing in response.

Its aim is to provide options to reduce service backlogs for those who are addressing this challenge in their national contexts.

Our ultimate goal, as agreed in the European Programme of Work 2020–2025, is to provide better health services that deliver more efficient, person-centred and high-quality care for all.

My thanks to the experts and partner organizations who have contributed to this informative and timely policy brief.

It is up to all of us to make the necessary steps to ensure that our health systems emerge from this health crisis stronger than before.

Dr Hans Henri P Kluge

WHO Regional Director for Europe

Our ultimate goal, as agreed in the European Programme of Work 2020–2025, is to provide better health services that deliver more efficient, person-centred and high-quality care for all.

Key messages

- Postponement of non-emergency (elective) procedures to keep capacity available for COVID-19 patients, and to avoid infections, has led to backlogs of care in virtually all countries.

- As each delay in diagnosis and treatment may worsen health prospects, health systems have sought to understand the extent of the backlogs and their drivers, and then employed a wide range of policies to address them.

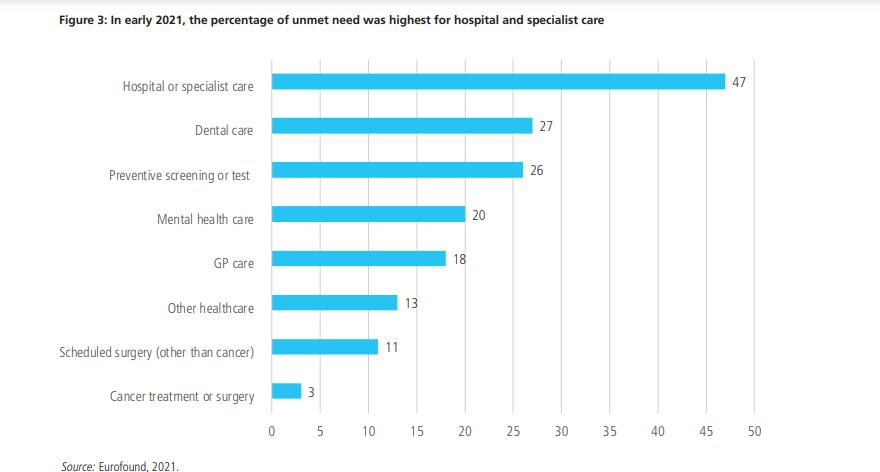

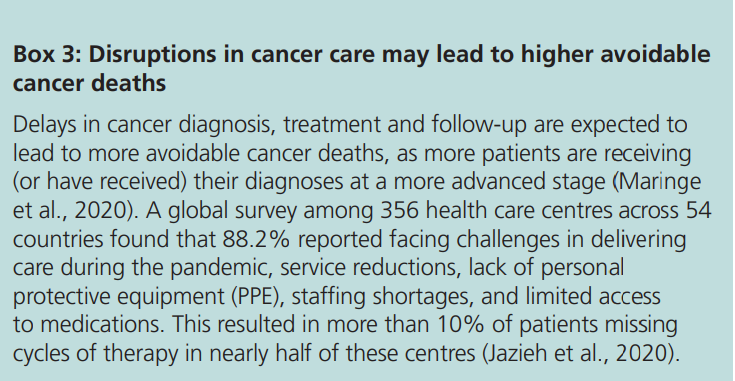

- The disruptions have led to high unmet need for health care during the pandemic, especially in hospital and specialist care. Although the degree of disruption decreased towards the end of 2021, this did not apply to all services, including cancer care and routine vaccinations.

- Drivers that can increase the backlog include supply-side factors, such as: low numbers of health workers (even pre-COVID); lower staff productivity due to exhaustion and burnout; the increased cost of providing treatment in a safe environment; and changes to the payment systems which may have weakened incentives to provide other care. Demand-side factors include: increasing demand for care fuelled by the availability of new technologies; and changed health needs due to ageing and rising chronic conditions (including long COVID).

- Drivers that can decrease the backlog include supply-side factors, such as: the availability of workforce and infrastructure; higher financial capacity to fund additional supply and absorb the backlog more quickly; and access to new technologies and digital solutions enabling more efficient treatment. On the demand side, fear of infection may lead to a temporary or permanent reduction in demand, but this can increase the extent of unmet need.

- Pre-pandemic waiting times and missed care during the pandemic mean that restoring care to previous levels will not be enough to overcome the backlogs.

To clear them (the backlogs), health systems have employed three broad strategies:

- Increasing the supply of workforce and staffing

- Improving productivity, capacity management and demand management

- Investing in capital, infrastructure and new community-based models of care,

Increasing the supply of workforce and staffing by introducing new professional roles and competencies; flexible recruitment and training; and improving work conditions, including offering mental health support and better compensation.

Improving productivity, capacity management and demand management, which includes separating planned and unplanned care; introducing financial incentives to clear the backlog; expanding access to telehealth services; implementing demand-side prioritization policies; and better spreading patients across the available capacity.

Investing in capital, infrastructure and new community-based models of care, for example, by upgrading health infrastructure and facilities; investing in primary and community care; expanding digital infrastructure; and expanding home care and rehabilitative capacity.

- Clearing backlogs as quickly as possible will be critical for maintaining health gains achieved before the pandemic and avoiding increasing excess mortality.

- Policies to support and protect health workers should be prioritized while at the same time improving workforce planning and workforce availability, which remain inadequate in many countries.

- It is important that policies that further rationalize health care delivery, such as reducing waste and increased use of digital solutions, do not increase inequalities in utilization and health.

Executive summary

As COVID-19 cases started to rise in early 2020 and hospitalization rates increased, health systems began to postpone non-emergency (elective) procedures to keep capacity available for COVID-19 patients, and to avoid elective patients being infected.

This has subsequently led to longer waiting lists (number of people waiting for care) and waiting times (how long they must wait) in virtually all countries.

The additional cumulated number of patients on the waiting lists due to COVID-19 is commonly referred to as the care backlog.

With each delay in diagnosis and treatment possibly leading to worse health, prolonged recovery and decreased chances of survival, countries have been taking steps to address these growing care backlogs while maintaining dual delivery of COVID and non-COVID services.

What do we know about the degree of service disruption and size of backlog?

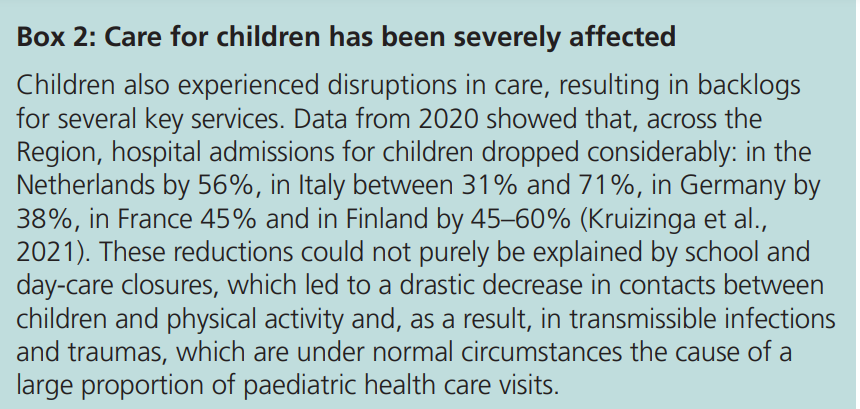

Health service provision was disrupted in virtually all European countries to differing degrees, gradually expanding from hospital, dental and mental health services to include all areas of care.

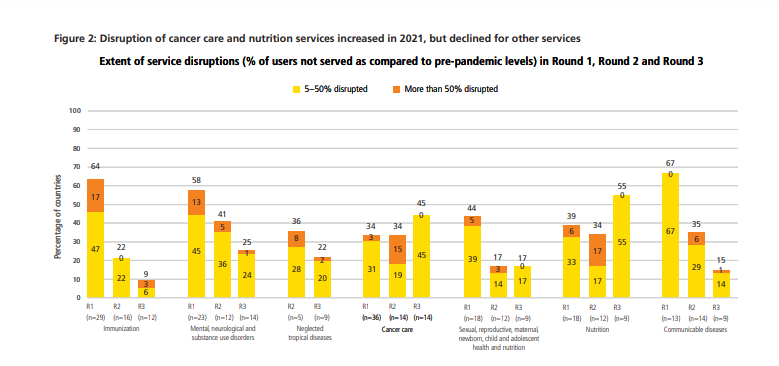

The degree of disruption decreased towards the end of 2021, but not for all services — including first-contact services, such as cancer care and nutrition services.

Even as COVID-19 vaccinations have been rolled out across the Region, the number of countries experiencing disruptions in routine facility-based immunization services has increased, affecting mostly children and adolescents.

These disruptions have led to high unmet need for health care during the pandemic, with data from the European Union (EU) showing that this especially affected hospital and specialist care, but with large variation between countries.

Although some countries managed to restore pre-pandemic levels of service delivery, in other countries waiting times only continued to increase.

Even where provision has been brought back to previous levels, existence of pre-pandemic waiting times and the increase in the number of patients on the waiting lists during the pandemic mean that this will not be enough to overcome the backlogs.

Although some countries managed to restore pre-pandemic levels of service delivery, in other countries waiting times only continued to increase.

What are the drivers of waiting times, waiting lists and backlog during and following the COVID-19 pandemic?

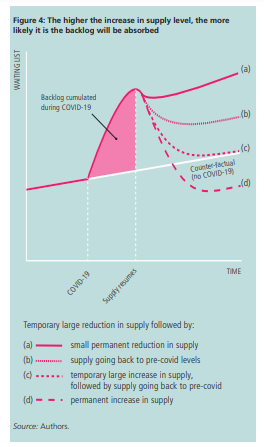

The pandemic put a halt to the number of patients being treated, thus generating a greater mismatch between the supply of and demand for health care services, translating into longer waiting lists and waiting times.

Other supply- and demand-side factors, not necessarily related to the COVID-19 pandemic, also influence the size of the care backlog over time.

Policy interventions to decrease backlogs should thus target both the supply- and demand-side factors when considering the local context.

The pandemic put a halt to the number of patients being treated, thus generating a greater mismatch between the supply of and demand for health care services, translating into longer waiting lists and waiting times.

- Drivers that can increase backlogs include supply-side factors such as the low number of health workers (even pre-COVID-19); staff exhaustion and burnout, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorders (which are compounded by pre-existing workforce shortages and reduce productivity); the increased cost of providing treatment in a safe environment (e.g. tighter hygiene protocols); and changes to the payment systems that prioritized COVID-19 services, which may have weakened incentives to address the backlog of care. On the demand side, new technologies and treatments, rising expectations of patients, and trends such as population ageing and the rise of chronic conditions (including long COVID) can all increase demand for care.

- Drivers that can decrease backlogs include the availability of workforce and infrastructure; higher financial capacity to fund additional supply; and access to new technologies and digital solutions that support more efficient provision of care.

On the demand side, fear of infection can lead to a temporary or permanent reduction in demand, but this may increase the extent of unmet need and may have detrimental health consequences.

Which policies are countries using to tackle their backlogs?

Health systems have been using a wide range of policies to reduce backlogs.

These efforts have to carefully balance tensions between actions that help catch up on care as quickly as possible in the near term with strategies that build capacity over the long term to meet health needs more sustainably in the future. The policies to address backlogs fall within three broad strategies:

1.Increasing the supply of workforce and staffing includes introducing new professional roles and competencies, flexible recruitment and training, and improving work conditions of the health workforce, such as by offering mental health support and better compensation.

2.Improving productivity, capacity management and demand management encompasses a host of policies, including separating planned and unplanned care; extending hours of care delivery; introducing financial incentives to clear backlogs; introducing maximum waiting-time targets; expanding access to telehealth services and virtual models of care; and implementing demand-side prioritization policies.

Lastly, there may be scope to better spread patients across available capacity and explore the potential of cross-border care by treating certain patients abroad.

3.Investing in capital, infrastructure and new community-based models of care enables more long-term solutions that include upgrading health infrastructure and facilities; investing in primary and community care; expanding digital infrastructure; and expanding home care and rehabilitative capacity.

Important challenges remain

Clearing care backlogs as quickly as possible will be critical for maintaining health gains achieved before the pandemic and avoiding increasing excess mortality.

It is still uncertain how much capacity will be needed to care for COVID-19 patients, how much is needed to reduce the backlog, and how many ‘missing patients’ with unmet needs there are.

Furthermore, many of the policies that can reduce backlogs are demanding on an already overstretched workforce.

This places increasing pressure on health workers, putting them at increased risk of absenteeism and burnout.

Therefore, policies to support and protect health workers should be prioritized alongside improving workforce planning and workforce availability, both of which remain inadequate in many countries.

In this process, it is important that policies that further rationalize health care delivery (including by reducing waste and inappropriate care, and making increased use of digital solutions), do not increase inequalities in utilization and health.

In this process, it is important that policies that further rationalize health care delivery (including by reducing waste and inappropriate care, and making increased use of digital solutions), do not increase inequalities in utilization and health.

Clearing care backlogs as quickly as possible will be critical for maintaining health gains achieved before the pandemic and avoiding increasing excess mortality.

Conclusions

- Clearing backlogs is critical for maintaining health gains achieved before the pandemic

- Policies to support and protect health workers should be prioritized but workforce planning and availability remain inadequate in many countries and should also be addressed

- It is important that policies to recover from backlog do not inadvertently increase inequalities

1.Clearing backlogs is critical for maintaining health gains achieved before the pandemic

This policy brief provides an inventory of policies that can together play a role in reducing the backlog of health services that has affected virtually all countries during and after the pandemic.

If health systems do not manage to reduce the backlog, they risk worsening health outcomes and wasting important health gains made in the pre-pandemic years.

Countries have been affected by care backlogs due to COVID-19 to varying degrees.

A great deal of uncertainty remains as to how much capacity will be needed to care for COVID-19 patients, how much will be required to reduce the backlog, and how many ‘missing patients’ with unmet needs there are.

Indeed, backlogs and waiting lists are dynamic and therefore flexible policies that will increase health service supply flows and can absorb unexpected changes in supply and demand need to be implemented, rather than just one off increases in supply.

A key requirement is the systematic collection of reliable and meaningful waiting time data, which some countries are not yet doing.

2.Policies to support and protect health workers should be prioritized but workforce planning and availability remain inadequate in many countries and should also be addressed

Some of the policies described in this brief are particularly demanding on the health workforce.

For example, strategies to boost elective capacity in the short term, like surgical hubs and standalone elective facilities, may have come with unrealistic assumptions about the workforce available to staff them, which will undermine their effectiveness in the short to medium term.

Similarly, addressing the care backlog with (well-deserved) bonuses and better payments and salaries may result in short-term gains but will not protect the workforce from exhaustion or burnout.

Thus, in many countries, having a large enough health workforce will remain a main bottleneck for years to come.

This puts increasing pressure on health workers, making them at increased risk of absenteeism, mental health problems and possible burnout, all of which are increasingly seen across Europe.

Therefore, policies to support and protect health workers should be implemented in parallel, and their wellbeing should be a top priority and a long-term concern.

Yet, even with these efforts, there are limits to what measures can achieve when it comes to addressing care backlogs given the insufficient numbers of qualified health workers in the pipeline and global competition for these limited numbers of staff.

This speaks to a broader problem of inadequate workforce planning and cross-government coordination to alleviate the staffing pressures confronting many systems.

Many health systems lack the prognostic assessments of future staffing needs required to be able to develop informed workforce strategies, and they vary in the levels and granularity of appropriate data available to them.

3.It is important that policies to recover from backlog do not inadvertently increase inequalities

In the future, countries may consider policies that further rationalize the supply of health services and demand for health care (by reducing waste and inappropriate care), but if not done carefully, this may increase inequalities in utilization and health.

In addition, the shift to more use of digital solutions will differentially impact patients and could also carry the risk of widening inequalities of access.

Therefore, it appears that countries have a real opportunity to make a strong case for reforms that address longstanding gaps, inefficiencies and inequalities in the health system, including funding gaps in some countries.

Investments in new models of care, which shift more care towards primary health and community care, and which prioritize medical and social outreach to vulnerable groups, should be a central part of these discussions, so that countries do not just build back to what they had before but instead aim for something better.

Investments in new models of care, which shift more care towards primary health and community care, and which prioritize medical and social outreach to vulnerable groups, should be a central part of these discussions, …

Originally published at https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int

About the authors and affiliations:

Ewout van Ginneken,

European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies,

Berlin University of Technology, Berlin, Germany

Sarah Reed,

Nuffield Trust, London, UK

Luigi Siciliani,

Department of Economics and Related Studies,

University of York, UK

Astrid Eriksen,

Berlin University of Technology, Berlin, Germany

Laura Schlepper,

Nuffield Trust, London, UK

Florian Tille,

European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, London, UK

Tomas Zapata,

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark

RELATED ARTICLES