Health Transformation Institute (HTI)

research institute, knowledge portal and advisory consulting

Joaquim Cardoso MSc*

Founder, and Chief Researcher & Editor

December 1, 2022

MSc* from London Business School

MIT Sloan Masters Program

Senior Advisor for Health Transformation & Digital Health

It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over…but It’s Never Over — Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

NEJM

Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.

December 1, 2022

A bit of reflection is inevitable.

As I prepare to step down from my dual positions at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), where I have been a physician-scientist for 54 years and the director for 38 years, a bit of reflection is inevitable.

As I think back over my career, what stands out most is the striking evolution of the field of infectious diseases and the changing perception of the importance and relevance of the field by both the academic community and the public.

I completed my residency training in internal medicine in 1968 and decided to undertake a 3-year combined fellowship in infectious diseases and clinical immunology at NIAID.

Unbeknownst to me as a young physician, certain scholars and pundits in the 1960s were opining that with the advent of highly effective vaccines for many childhood diseases and a growing array of antibiotics, the threat of infectious diseases — and perhaps, with it, the need for infectious-disease specialists — was fast disappearing.1

Despite my passion for the field I was entering, I might have reconsidered my choice of a subspecialty had I known of this skepticism about the discipline’s future.

Of course, at the time, malaria, tuberculosis, and other diseases of low- and middle-income countries were killing millions of people per year. Oblivious to this inherent contradiction, I happily pursued my clinical and research interests in host defenses and infectious diseases.

When I was several years out of my fellowship, I was somewhat taken aback when Dr. Robert Petersdorf, an icon in the field of infectious diseases, published a provocative article in the Journal suggesting that infectious diseases as a subspecialty of internal medicine was fading into oblivion.2

In an article entitled “The Doctors’ Dilemma,” he wrote regarding the number of young physicians entering training in the various internal medicine subspecialties, “Even with my great personal loyalties to infectious disease, I cannot conceive a need for 309 more infectious-disease experts unless they spend their time culturing each other.”

Of course, we all aspire to be part of a dynamic field. Was my chosen field now static?

Dr. Petersdorf (who would become my friend and part-time mentor as we and others coedited Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine) gave voice to a common viewpoint that lacked a full appreciation of the truly dynamic nature of infectious diseases, especially regarding the potential for newly emerging and reemerging infections.

In the 1960s and 1970s, most physicians were aware of the possibility of pandemics, in light of the familiar precedent of the historic influenza pandemic of 1918, as well as the more recent influenza pandemics of 1957 and 1968.

However, the emergence of a truly new infectious disease that could dramatically affect society was still a purely hypothetical concept.

That all changed in the summer of 1981 with the recognition of the first cases of what would become known as AIDS.

The global impact of this disease (AIDS) is staggering:

since the start of the pandemic, more than 84 million people have been infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, of whom 40 million have died.

In 2021 alone, 650,000 people died from AIDS-related conditions, and 1.5 million were newly infected. Today, more than 38 million people are living with HIV.

since the start of the pandemic, more than 84 million people have been infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, of whom 40 million have died.

In 2021 alone, 650,000 people died from AIDS-related conditions, and 1.5 million were newly infected.

Today, more than 38 million people are living with HIV.

Although a safe and effective HIV vaccine has not yet been developed, scientific advances led to the development of highly effective antiretroviral drugs that have transformed HIV infection from an almost-always-fatal disease to a manageable chronic disease associated with a nearly normal life expectancy.

Given the lack of global equity in the accessibility of these lifesaving drugs, HIV/AIDS continues, exacting a terrible toll in morbidity and mortality, 41 years after it was first recognized.

If there is any silver lining to the emergence of HIV/AIDS, it is that the disease sharply increased interest in infectious diseases among young people entering the field of medicine.

Indeed, with the emergence of HIV/AIDS, we sorely needed those 309 infectious-disease trainees that Dr. Petersdorf was concerned about — and many more.

To his credit, years after his article was published, Dr. Petersdorf readily admitted that he had not fully appreciated the potential impact of emerging infections and became something of a cheerleader for young physicians to pursue careers in infectious diseases and specifically in HIV/AIDS practice and research.

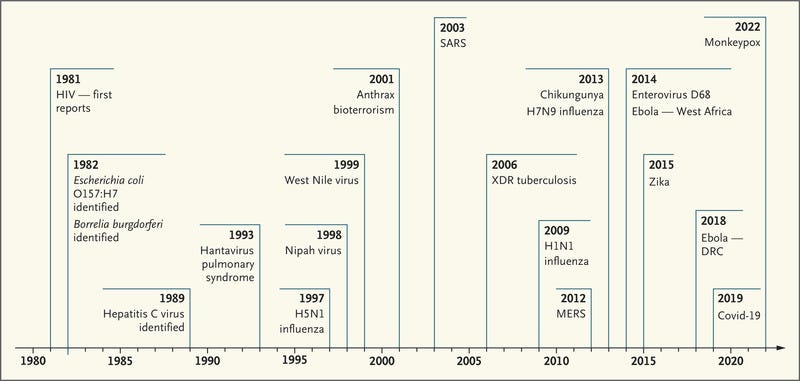

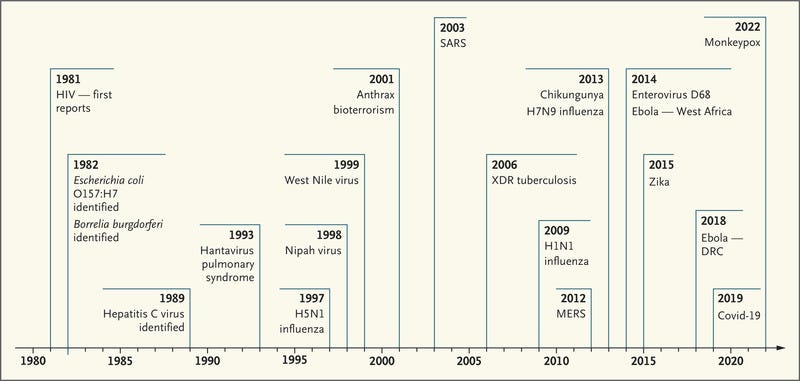

Selected Landmark Events in Infectious-Disease Emergence Leading up to and during the Author’s Four-Decade Tenure as NIAID Director.

Of course, the threat and reality of emerging infections did not stop with HIV/AIDS.

During my tenure as NIAID director, we were challenged with the emergence or reemergence of numerous infectious diseases with varying degrees of regional or global impact (see timeline).

Included among these were the first known human cases of H5N1 and H7N9 influenza; the first pandemic of the 21st century (in 2009) caused by H1N1 influenza; multiple outbreaks of Ebola in Africa; Zika in the Americas; severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by a novel coronavirus; Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) caused by another emergent coronavirus; and of course Covid-19, the loudest wake-up call in more than a century to our vulnerability to outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases.

The devastation that Covid-19 has inflicted globally is truly historic and highlights the world’s overall lack of public health preparedness for an outbreak of this magnitude.

… Covid-19, is the loudest wake-up call in more than a century to our vulnerability to outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases.

One highly successful element of the response to Covid-19, however, was the rapid development — enabled by years of investment in basic and applied research — of highly adaptable vaccine platforms such as mRNA (among others) and the use of structural biology tools to design vaccine immunogens.

The unprecedented speed with which safe and highly effective Covid-19 vaccines were developed, proven effective, and distributed resulted in millions of lives saved.3

The unprecedented speed with which safe and highly effective Covid-19 vaccines were developed, proven effective, and distributed resulted in millions of lives saved.

The same can now be said of the field of infectious diseases, particularly with the tools we now have for responding to emerging infectious diseases, such as the rapid and high-throughput sequencing of viral genomes; the development of rapid, highly specific multiplex diagnostics; and the use of structure-based immunogen design combined with novel platforms for vaccines.4

If anyone had any doubt about the dynamic nature of infectious diseases and, by extension, the discipline of infectious diseases, our experience over the four decades since the recognition of AIDS should have completely dispelled such skepticism.

Today, there is no reason to believe that the threat of emerging infections will diminish, since their underlying causes are present and most likely increasing.

The emergence of new infections and the reemergence of old ones are largely the result of human interactions with and encroachment on nature.

As human societies expand in a progressively interconnected world and the human–animal interface is perturbed, opportunities are created, often aided by climate changes, for unstable infectious agents to emerge, jump species, and in some cases adapt to spread among humans.5

The emergence of new infections and the reemergence of old ones are largely the result of human interactions with and encroachment on nature.

An inevitable conclusion of my reflections on the evolution of the field of infectious diseases is that the pundits of years ago were incorrect and that the discipline is certainly not static; it is truly dynamic.

In addition to the obvious need to continue to improve on our capabilities for dealing with established infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, among others, it is now clear that emerging infectious diseases are truly a perpetual challenge.

As one of my favorite pundits, Yogi Berra, once said, “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Clearly, we can now extend that axiom: when it comes to emerging infectious diseases, it’s never over.

As infectious-disease specialists, we must be perpetually prepared and able to respond to the perpetual challenge.

An inevitable conclusion of my reflections on the evolution of the field of infectious diseases is that the pundits of years ago were incorrect and that the discipline is certainly not static; it is truly dynamic.

In addition to the obvious need to continue to improve on our capabilities for dealing with established infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, among others, it is now clear that emerging infectious diseases are truly a perpetual challenge.

As infectious-disease specialists, we must be perpetually prepared and able to respond to the perpetual challenge.

Author Affiliations

Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.

From the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Originally published at https://www.nejm.org.

RELATED ARTICLES