Nikkei Asia

ERWIDA MAULIA and ISMI DAMAYANTI, Nikkei staff writers

November 24, 2021

This is an excerpt of the article “Seen and not heard: health workers in Asia bullied into silence”, republished with the title above, and with the key messages summarized by the editor of the blog.

KEY MESSAGES (Edited by the author of the blog)

Key messages about deaths

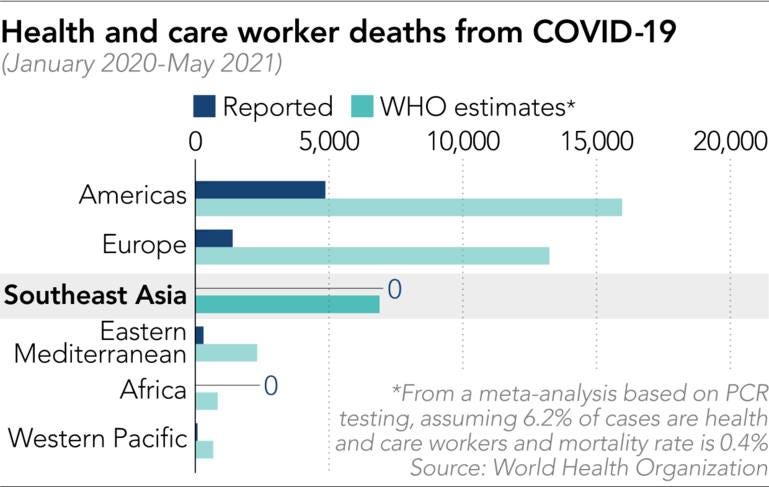

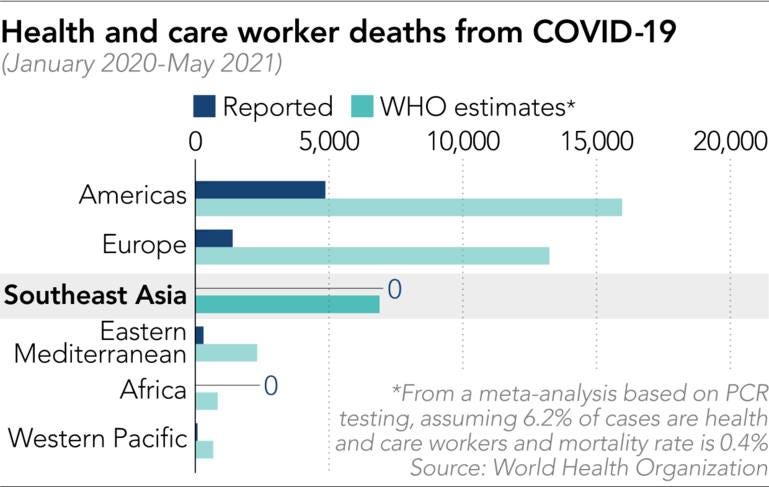

The World Health Organization, in an October report, said deaths among health workers during the pandemic have been vastly undercounted.

The WHO estimates between 80,000 and 180,000 health and care workers worldwide died from COVID-19 from January 2020 to May 2021.

That is much higher than figures reported to the health body, which came to 6,643 deaths.

Key messages about Asia

Seen and not heard: health workers in Asia bullied into silence

Brutal hours, poor conditions, low pay — from Indonesia to the Philippines, the region’s carers have learned to keep quiet

Urgent action needed

The global office of Project Hope warned in a statement that “already fragile health systems around the globe are at an even higher risk of collapsing if the emphasis is not put on protecting the global health workforce.”

Tom Kenyon, chief health officer at the nongovernmental organization, said losing health care workers by any means — deaths from COVID-19, emigration to better working conditions or resignations — translates to a loss of knowledge, especially for countries with low health care capacity.

He added that the “unthinkable suffering” experienced by health workers “may bring a lifetime of mental health battles and nightmare memories. We need to guarantee their protection now and throughout their careers.”

“So I hope the government will consistently pay attention to health workers’ rights … to work safely and under protection, and to express our opinions. Don’t let the same old problems repeat.” (Fen)

FULL VERSION

Seen and not heard: health workers in Asia bullied into silence

Brutal hours, poor conditions, low pay — from Indonesia to the Philippines, the region’s carers have learned to keep quiet

JAKARTA — Fentia Budiman had just woken up from two-hours of sleep following an overnight shift at Indonesia’s largest COVID-19 isolation center in Jakarta. She and another nurse tended 60 to 70 patients on one of the hospital’s floors, grabbing sleep whenever she could in between shifts.

When she checked her phone, Fen, as she prefers to be called, was greeted by dozens of missed calls, and several messages summoning her to a meeting room in the Athletes’ Village, a sprawling apartment complex built to host athletes during the 2018 Asian Games. Since March 2020 it has been a massive COVID-19 ward for patients with mild to moderate symptoms.

The petite, 27-year-old nurse arrived only to discover she was nearly the only woman in the room, with about 20 soldiers and police officers surrounding her. She was told to cancel a news conference she and several colleagues had planned for later that day at which they had planned to speak out about months of delayed bonuses for hundreds of nurses and doctors who have volunteered to work at the facility — their only source of income. These had been promised by the government since last year, and all previous attempts to ask about the delays had met a dead end, eliciting only unsympathetic responses from higher-ups.

“If you insist on speaking up to the public, there will be consequences,” Fen said, repeating what the leader of the group in the room told her, in a recent interview with Nikkei Asia. “Your nursing license will be revoked. If you were a man, we would have already beaten you up. And … we will fire you.”

Fen initially refused to back down, but after five hours of interrogation that included shouting, threats and table-slamming, she gave up. She was made to write and sign a letter stating she would cancel the news conference and another apologizing to the management of the isolation center.

Fentia Budiman, a nurse from Jakarta, told Nikkei Asia that she was threatened with dismissal when she attempted to speak up about delayed bonuses promised to her and her fellow health workers. (Photo by Dimas Ardian)

“There were just too many pressures in that room,” she sighed, and then teared up. She paused. “There was too much intimidation, too many questions. And I was very tired at that time because I just finished my shift and only had a two-hour sleep.”

“I thought my answers were clear, that I didn’t do anything wrong. I was just expressing my views as a health worker, and those are about crucial issues that the government must listen to. But why was I being shouted at? Why did they threaten me?”

Fen said that apart from “psychological attacks,” which included a threat to charge her for defamation, she was not harmed physically.

The next day she was told that she could no longer work in the facility after working there for over a year. A few days later, the much-delayed bonuses were finally paid. Fen has since been working as a vaccine administrator and has joined the health division of a new political party.

Muhammad Arifin, then spokesman of the facility, said in an interview with a local TV station in May that the delays were caused by lengthy verification processes by state auditors that affected a lot of hospitals. He said that Fen was not fired, but that her monthly contract was simply not extended.

He denied “such a thing as intimidation” against Fen, claiming that fellow health workers from the military and police ranks in that room were only “seeking clarifications.” He accused Fen of seeking fame and said the group that she had co-founded last year, the Indonesian Health Workers Network, was illegal.

“I’m not abandoning, let alone silencing those who speak out. In fact, I was the one who raised the issue first. But we have procedures here that should be followed,” Arifin said. He also reminded health workers who have chosen to volunteer at the Athletes’ Village that they are “on a humanitarian mission,” and that they are “not laborers.” “The important thing is to work well … [to help] people heal.”

Health care workers treat a COVID-19 patient in an emergency tent in Sleman, Yogyakarta Province, Indonesia, on July 4. Many doctors and nurses have been working grueling hours with few financial rewards since the pandemic began. © Antara Foto/Reuters

When approached by Nikkei, Mintoro Sumego, a spokesman for the Athletes’ Village Emergency Hospital, said he knew nothing about the case, adding that security personnel and civilian health workers there are “coordinating well.” An army spokesman did not respond to several requests for comment.

The episode highlights the fracturing relationship between the Indonesian government and health workers as the second year of the pandemic draws to a close. In Indonesia and many other countries, doctors and nurses have resorted to political agitation and the language of human rights to advocate for themselves as governments stall or renege on promised monetary incentives and fail to make improvements to unsafe working conditions.

Edhie Rahmat, executive director for Indonesia at Project Hope, an international health and humanitarian relief organization, said health workers in many countries “have become unexpected targets during the COVID-19 pandemic, and they have been targeted from all fronts.”

“Early on in the pandemic, they were celebrated, but as the response to the pandemic became highly politicized, the praise has turned into blaming and attacks,” he said.

Fentia (“Fen”) was fired after raising concerns about health workers’ rights and salaries. She now administers vaccines, and continues to advocate for workers’ rights as member of the health division of a new political party.

Across Asia, doctors and nurses report having to work brutally long hours in extremely hazardous conditions for low pay, without much hope that the situation will end.

Southeast Asia — which has seen some of the world’s worst COVID-19 caseloads in countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines — is also among the most difficult environments for health workers. They are leaving the profession in droves, so much so that in Vietnam and elsewhere health workers face penalties for quitting their jobs.

However, the same toxic pressure exists even in mature democracies like the U.K., Italy, and the U.S., according to an October report by human rights group Amnesty International, citing “an alarming global trend of repression,” including against health workers.

“Throughout the pandemic, governments have launched an unprecedented attack on freedom of expression, severely curtailing peoples’ rights. Communication channels have been targeted, social media has been censored, and media outlets have been closed down,” said Rajat Khosla, Amnesty International’s senior director for research advocacy and policy, adding that “journalists and health professionals have been silenced and imprisoned.”

COVID-19 has revealed the lack of preparedness and slowness of response to a pandemic in almost every country, Rahmat said. “In such circumstances, countries have tried to impose their own narratives, and in some cases spread misinformation. Some countries went as far as silencing voices that would offer different narratives.”

The World Health Organization, in an October report, said deaths among health workers during the pandemic have been vastly undercounted.

The WHO estimates between 80,000 and 180,000 health and care workers worldwide died from COVID-19 from January 2020 to May 2021.

That is much higher than figures reported to the health body, which came to 6,643 deaths.

Regionwide struggle

In Malaysia, more than 8,000 doctors took part in a strike for better terms of employment in July, according to “Hartal Doktor Kontrak,” a local group that represents contract doctors. The doctors, who say the terms of their employment were guaranteed by the government, stopped work for a few hours in protest. Some of the movement’s leaders were later interrogated, according to Amnesty International. Hartal Doktor Kontrak plans to hold another rally in December.

After the first protest, the government responded by offering training and to extend their contracts from two to four years. The doctors group rejected the offer: Calling it “just bait to get us to stop speaking up,” in a recent Twitter post.

Brian Yap of Amnesty International Malaysia told Nikkei that police interrogations of the protesting contract doctors are “an alarming violation of human rights.”

“It’s one of many examples of the Malaysian government’s failure to protect essential workers and frontliners in the fight against COVID-19,” he said.

“The investigations into the doctors have so far not led to any further action, but they should not have been carried out in the first place,” Yap said, adding that the government should look into the concerns of the doctors and protect all frontline workers instead of criminalizing those who speak up.

Health care workers in Kuala Lumpur attend a walkout to press for better job security and benefits on July 26. Around 22,000 contract doctors took part in the protest. © Reuters

Poor pay is also a source of anger for Filipino health workers. On Nov. 16, clad in personal protective gear, dozens marched toward the gate of the Philippine Senate in Manila, calling for higher budgets for health, higher salaries for health care staff and for more hiring of health care workers.

“For almost two years now, we health workers [have been] at the forefront, risking our life and safety in fighting COVID-19 pandemic. And many from our ranks have died due to [this] virulent virus,” said Benjamin Santos, secretary-general of the Alliance of Health Workers. “We are being called heroes, but never been truly valued because until now our salaries remain low.”

The Philippine government says a little over 100 health workers have died from COVID-19 in the Philippines, which has experienced Southeast Asia’s second-worst virus outbreak, after Indonesia. The recent protest is one in a series of rallies held by health workers this year. Earlier protests centered on the delayed payments of benefits and special risk allowances by the government that were mandated by law.

Filipino health care workers hold up signs in Manila on Sept. 1 to demand better pay, more government spending on health care and the hiring of additional medical staff. © Reuters

In Vietnam, which is battling a new wave of infections, the Health Ministry in September said doctors and nurses contributing to its pandemic control should be rewarded, but also threatened those who quit with “administrative discipline or [deprivation of] the right to use their practicing certificates,” according to local news portal VnExpress.

In Myanmar, health workers have been caught in the military government’s crackdown on civilians, even as they battled the country’s worst outbreak around July. “By relentlessly pursuing medical workers, threatening them and arresting them, the military authorities have driven the country’s already fragile health care system into the ground during a global pandemic,” Amnesty wrote on July 30.

Collapsed on the floor

Indonesia’s case numbers have steadily declined since their July to August peak, when the country briefly overtook India as the world’s coronavirus epicenter, with more than 50,000 infections and almost 2,000 deaths per day. Now there are about 360 new cases and 10 deaths daily.

One Indonesian nurse described the harrowing time in an interview. Ratih (not her real name) said the hospital where she works, one of the largest in Indonesia’s Central Java Province, was so overloaded with patients between June and July that it had to set up tents at the parking lot.

Ambulance sirens were wailing nonstop, oxygen supplies were running out, and the morgue handled 20 to 40 dead bodies a day, Ratih said. Among those who died were doctors and nurses she had treated in the intensive care unit who had come from smaller hospitals in neighboring towns.

“It was a very terrifying situation,” Ratih, who gave birth to a son last year, told Nikkei. “I had such a high level of stress that my breast milk barely came in. I was scared I would infect my baby, my family. I once caught a fever, which spread all over my body. Luckily my tests turned out negative.”

Indonesian health care workers prepare to treat patients in January at an emergency hospital for COVID-19 set up in the Athletes Village in Jakarta. Many workers have fallen ill while caring for others. © Antara Foto/Reuters

Ratih preferred to use a pseudonym because the public hospital she works at strictly forbids employees from sharing work-related information publicly. A fellow nurse was admonished by the hospital management after a photo she shared on Facebook showing an emergency room overflowing with patients went viral, Ratih said.

Other health workers approached for this story declined to give interviews, even anonymously, despite complaining about delayed bonus payments, overwork or having to buy their own personal protective equipment. They expressed fears that their employers would somehow discover their identities.

As many as 502 Indonesian health workers died in July alone, during the peak of the country’s COVID-19 outbreak, even though most of them had been vaccinated twice with China’s Sinovac vaccine. The government subsequently decided to give health workers boosters using the Moderna vaccine. In all, 2,066 died as of Nov. 18, according to local watchdog LaporCovid-19.

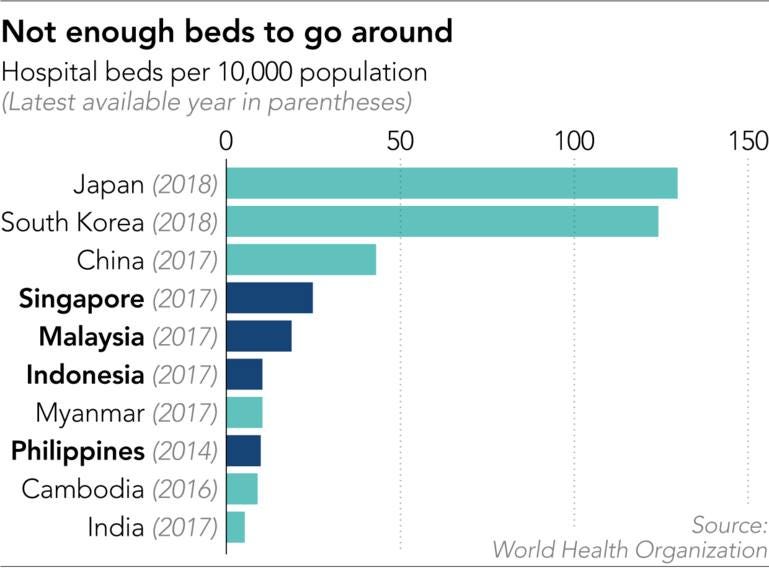

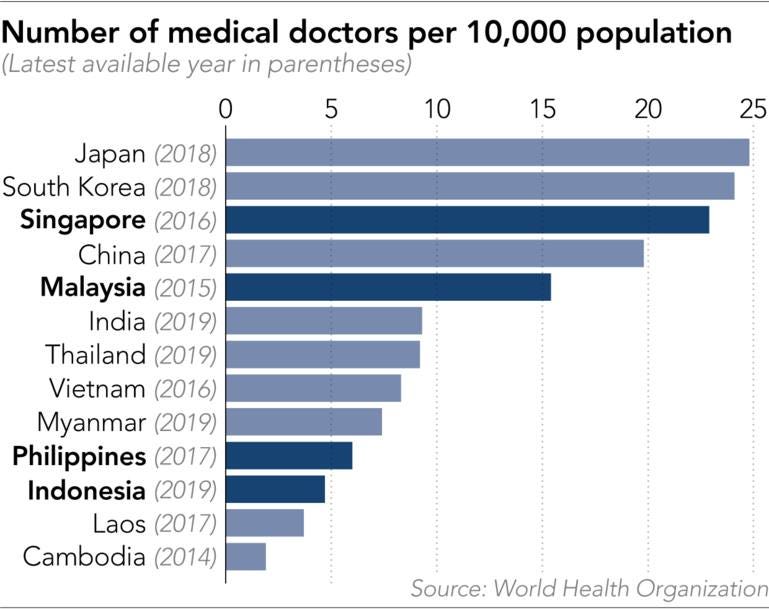

The delta variant outbreak, which began in Jakarta and other provinces on the island of Java, spread to other regions across the sprawling archipelago, straining Indonesia’s already limited health care capacity and personnel beyond their limits.

Bawono, a general practitioner at a private hospital in Makassar, the largest city in eastern Indonesia, said he worked many double shifts a few months back, as patients continued to flow in, “all suffering from severe asphyxiation.”

Eventually his body gave out: One day Bawono, who only gave his surname, collapsed on the floor while checking on a patient. He developed a fever, dry cough and lost his sense of smell. The symptoms pointed to COVID-19 and he tested positive, adding to the woes of his wife, a nurse, who had a miscarriage after being hospitalized with severe coronavirus symptoms earlier this year.

Another doctor in a city on Sumatra Island said she was “very grateful” if she could “sit for just five minutes to catch my breath in the hallway” amid many double shifts, and only finally got a proper rest when she caught the virus with mild symptoms.

“Never had we imagined a hospital in a small city like ours would be overwhelmed with so many patients, and us doctors collapsing one by one,” she said, recalling a day when the hospital ran out of its central oxygen supply for two hours while “even babies were in need of respiratory support.”

Despite the harrowing work, many Indonesian health workers have suffered pay cuts due the government’s cancellations of annual bonuses for civil servants, which hit public hospitals like Ratih’s, or because of declines in revenue at private hospitals as patients hold off on visits for fear of contracting the virus.

Incentives promised by the government for those treating COVID-19 patients seem like a rare bright spot in Indonesia. Under a policy introduced in March last year, nurses are eligible for a monthly pay bump of 7.5 million rupiah ($526) and general practitioners an extra 10 million rupiah.

Berry Adi Satria, a nurse in Indonesia’s Lampung Province, said the payment for his January to May incentives was only transferred in June, and he only got a fifth of the amount he should have received.

“Most health workers at my hospital experienced this too. We’ve tried to complain to the local health agency and also directly to the health ministry, but there has been no response so far,” Satria said, adding there were only slight delays in June to August payments.

Nurina Savitri of Amnesty International Indonesia said that while incentive delays dominated health workers’ complaints in 2021, their situation has improved somewhat in terms of job security compared with last year when over 300 contract health workers — especially nurses — were dismissed from their workplaces after protesting lack of personal protective equipment.

In some cases, those who complain have been met with intimidation and threats. LaporCovid-19 said its volunteers in some regions also have been subject to threats when seeking explanations from local health agencies.

“In one case, a health worker reported that a certain community health center had not received any incentives at all,” a volunteer at the watchdog said. “We contacted the local health agency, but instead of listening to our input, they threatened to track our team down.”

In many cases it is hospital management who have silenced their employees, with worries over public perceptions or problems with reimbursements of COVID-19 treatment costs from the government believed to be among the main reasons.

A medical worker sits in front of the corpse of a COVID-19 victim who died at a hospital in Bogor, Indonesia, on July 16. Between July and August, Indonesia saw 1,000–2,000 deaths from the virus each day. © AP

The Health Ministry has blamed the payment delays mostly on bureaucratic hurdles at local governments, and failures by these authorities to facilitate verification of health workers eligible for the program and bonus payments. Following the conflict between Fen and the Athletes’ Village, the ministry vowed to expedite the disbursements, and by late August reported that 41.3% of a total 9.18 trillion rupiah allocated for health worker incentives this year had been paid, up from just 3.8% as of early June.

When asked about intimidation and threats against health workers, Health Ministry spokeswoman Siti Nadia Tarmizi said: “We haven’t got information about this matter, but of course we’ll pay attention to this.”

Driven to resignation

Butch Olano, director of the Philippines chapter of Amnesty International, said there have been reports of health workers having trouble using public transportation because some drivers refused them service. Others have reported being assaulted by people fearful that they carry the virus.

He added that there have been “instances where government officials have been demonizing or verbally attacking health care workers who have spoken up about the condition of the health care system in the country, or questioned the priorities demonstrated” by policymaking bodies.

“No health care worker should be blamed or punished for doing their work, which is to save lives, while asking to protect their own,” said Rahmat of Project Hope Indonesia. “Every single day for the last 20 months, health care workers have put their lives on the front lines. They need much more recognition.”

A health worker tends to a COVID-19 patient in a chapel being used as an emergency coronavirus ward in Manila on Aug. 20. Doctors and nurses are overworked and underpaid, causing many of them to leave the Philippines to work overseas. © Reuters

In the Philippines, more than 1,000 nurses are seeking work abroad, according to Maristela Abenojar, president of Filipino Nurses United, an organization advocating nurses’ labor rights, but the government put a cap on the numbers of health workers who can be deployed overseas, fearing a labor shortage amid the health crisis. Filipino nurses are in demand in Europe and the Middle East.

Robert Mendoza, president of the Alliance of Health Workers, said there should also be mass hiring of health workers in the Philippines because hospitals are understaffed, adding, “Many workers have resigned or opted to retire early because they are dismayed and burned out.”

He added “mass walkouts” of hospital workers could happen on Nov. 24, when the group planned a large protest in Manila to further press the government for the release of allowances and benefits.

The strains are starting to show, even in wealthier nations with advanced health care systems like Singapore. Following the easing of social restrictions, the city-state recorded its worst COVID-19 outbreak in late October. It consistently reports more than 1,000 new daily cases, even though 85% of its population have been fully vaccinated.

Around 1,500 health workers in Singapore resigned in the first half of this year alone, versus about 2,000 annually before the pandemic struck. Health workers from abroad have quit in bigger numbers, with close to 500 people resigning between January and June, compared with around 500 in the whole of 2020 and 600 in 2019.

To keep them on the job, the government said some 56,300 public health care workers, including nurses and support staff, will get pay raises over the next two years. Nurses will have their monthly base salaries increased by 5% to 14%.

In addition, in November it was announced that public health care workers in Singapore will receive cash awards of up to 4,000 Singapore dollars ($2,942) for their role in fighting COVID-19.

“Our hospitals are feeling the manpower crunch. Signs of fatigue can be seen amongst our health care workers,” Singapore’s senior minister of state for health, Dr. Janil Puthucheary, told parliament in November when revealing the resignation figures.

A health worker examines a COVID-19 test kit at a testing center in Singapore on Sept. 28. Unable to cope with the pressures of the pandemic, more than 1,000 health care workers quit in the first half of this year. © Reuters

Urgent action needed

The global office of Project Hope warned in a statement that “already fragile health systems around the globe are at an even higher risk of collapsing if the emphasis is not put on protecting the global health workforce.”

Tom Kenyon, chief health officer at the nongovernmental organization, said losing health care workers by any means — deaths from COVID-19, emigration to better working conditions or resignations — translates to a loss of knowledge, especially for countries with low health care capacity.

He added that the “unthinkable suffering” experienced by health workers “may bring a lifetime of mental health battles and nightmare memories. We need to guarantee their protection now and throughout their careers.”

Fen, meanwhile, continues to advocate for health workers’ rights together with other members of the Indonesian Health Workers Network. Apart from the delays in bonus payments, one of the group’s current concerns is verbal and physical harassment against health workers by patients or family members who believe the pandemic to be some kind of a conspiracy, she said.

“We health workers have been committed to joining the fight against the pandemic since the beginning. But this feels like climbing up a mountain endlessly … while we also have to take care of our families’ needs,” Fen said.

“So I hope the government will consistently pay attention to health workers’ rights … to work safely and under protection, and to express our opinions. Don’t let the same old problems repeat.”

Additional reporting by Cliff Venzon in Manila, P Prem Kumar in Kuala Lumpur, and Dylan Loh in Singapore

Originally published at https://asia.nikkei.com on November 24, 2021.