JAMA Network — American Medical Association

Satish Gopal, MD1; Norman E. Sharpless, MD1

August 6, 2021

Additional Contributions: Peter Garrett, AB, Patti Gravitt, PhD, Pat Loehrer, MD, Doug Lowy, MD, and Kelli Marciel, MA.

Cancer imposes a profound burden on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where 65% of approximately 10 million global cancer deaths in 2020 occurred.1

Moreover, global cancer morbidity and mortality are increasing due to demographic and epidemiological transitions, with 16 million global cancer deaths projected in 2040, an estimated 69% of which will occur in LMICs.1

The lowest-income countries will experience the greatest proportional increases, with a projected near doubling of cancer deaths.1

COVID-19 is exacerbating global cancer morbidity and mortality because hospital and clinic shutdowns have forced many delayed or missed prevention and screening visits, evaluations for cancer-related symptoms, and cancer treatments in high-income countries and LMICs.

The global response to COVID-19 has demonstrated marked inequities, with escalating cases and limited access to vaccines and other control measures in LMICs.

Accelerating efforts to address COVID-19 in LMICs are encouraging, and this recommitment to health equity should extend to all populations and diseases.

Cancer strongly exemplifies global health inequities.

In high-income countries, the pace of recent progress against cancer is unprecedented.

- In the US, data from 2017 revealed the largest 1-year decline in cancer death rates until data from 2018 demonstrated an even steeper decline.2

- Advances in cancer prevention and screening have occurred, as well as record numbers of approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for oncology drugs and devices.

Despite such progress,

- there is virtually no access to these cutting-edge but high-cost therapeutics in many LMICs,

- and even access to older, proven, low-cost cancer therapies may be limited.

- Likewise, the dissemination of essential cancer control interventions in LMICs is inconsistent and incomplete.

There are numerous specific examples of global cancer health inequities.

- For cervical cancer, some countries may achieve the World Health Organization (WHO) incidence target of less than 4 cases per 100 000 population by the end of this decade.3

- However, many low-income countries with high cervical cancer incidence may not achieve this target by the end of this century, even under extremely optimistic coverage scenarios for preventive services.4

- Similarly, Burkitt lymphoma was discovered in Uganda in the 1950s and has been cured in more than 90% of children participating in clinical trials in high-income countries, but has been cured in only 30% to 60% of children in sub-Saharan Africa in contemporary studies.5

- Inequities in cancer clinical trials also exist, with only 8% of phase 3 randomized clinical trials in oncology between 2014 and 2017 having been conducted in LMICs.6

- Even for HIV-associated malignancies, cancers for which global cases are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, there are few clinical trials from the region.7

These inequities limit the ability to address cancer morbidity and mortality globally.

They also limit the ability to make progress for patients with cancers that are rare in their own countries but common in other parts of the world.

For example, liver cancer mortality rates have doubled in the US since 1980.2 However, no first-line treatment for advanced liver cancer yielded improved survival compared with sorafenib, which received FDA approval in 2007, until atezolizumab plus bevacizumab received FDA approval in 2020 based on a phase 3 clinical trial that enrolled 40% of the patients in Asia.8

Progress against cancer in high-income countries has not been serendipitous. It has resulted from strategic and sustained investments in research leading to discoveries that have been translated into effective interventions.

In the US, much of the recent progress can be traced to the National Cancer Act of 1971. The year 2021 marks the 50th anniversary of this landmark legislation, and also marks the 10th anniversary of the creation of a dedicated Center for Global Health at the US National Cancer Institute (NCI).9

The Center was established to incorporate cancer control into broader global health programs, foster relevant research throughout the NCI, and cultivate collaborations among researchers with shared global health objectives.9

When the Center was first established, it was noted that many cancer-related problems could only be solved by giving more attention to cancers in other parts of the globe.9

For example, studies that established the efficacy of community-based human papillomavirus vaccination and the efficacy of multiagent chemotherapy to treat Burkitt lymphoma relied on collaborations between the NCI and investigators in LMICs.

To fulfill President Biden’s exhortation to “end cancer as we know it,” it will be necessary to reduce cancer morbidity and mortality globally.

Past attention on LMICs has, at times, been more problematic than helpful.

- Often, investigators and institutions from high-income countries have advanced parochial scientific agendas through LMIC collaborations, which provide access to patients, biospecimens, data, and other resources in LMICs not available in their own high-income settings.

- At the same time, the knowledge generated has not always been meaningfully translated or applied to patients with cancer and populations in LMICs, including those who directly contributed to this knowledge.

Moving forward, goals should include more symmetric and equitable progress. Cancer control will be stronger and more resilient for everyone with development, testing, and deployment of effective interventions globally.

As the Center for Global Health prepares to enter its second decade, the Center has developed an updated 5-year strategy to address these issues and to renew the NCI’s commitment to a leadership role in global cancer research and control, with plans to review progress and update this strategy at the end of this 5-year period.10

During the last decade, global oncology as a scientific community has experienced tremendous growth.

This increase in interest, capacity, and opportunity provides a strong foundation for future discovery and dissemination efforts.

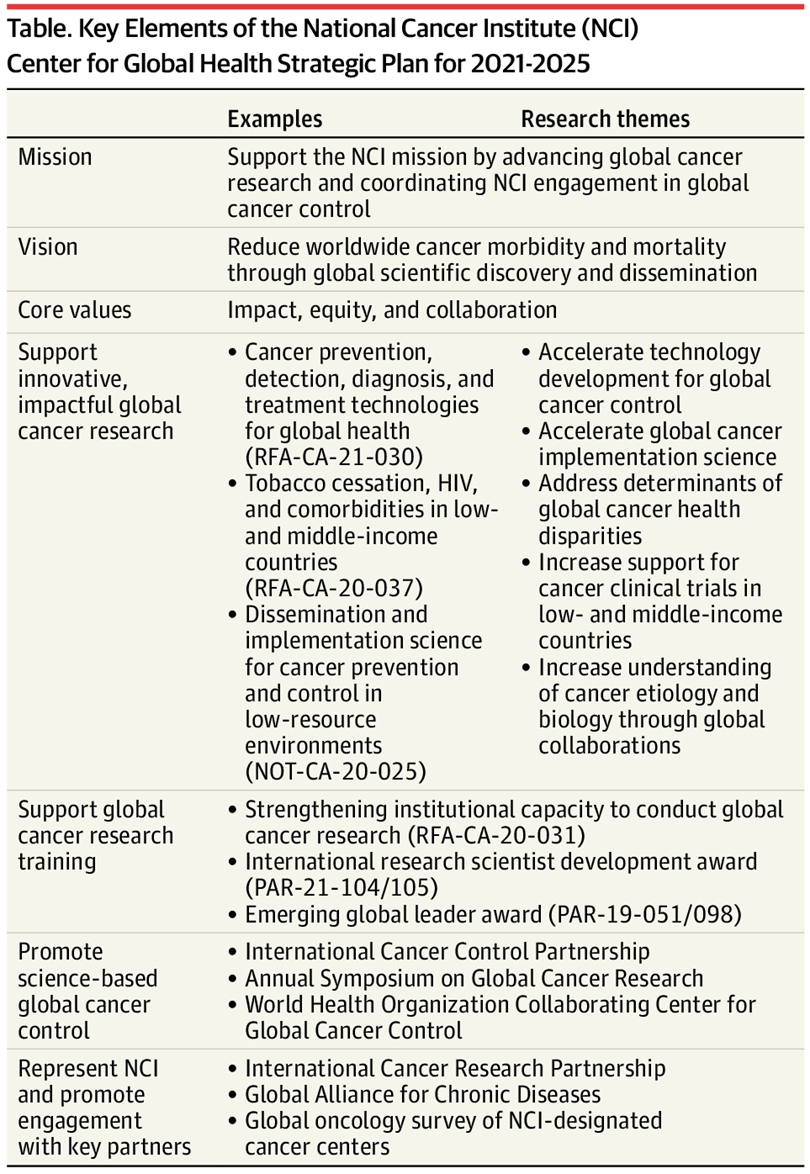

As highlighted in the Table and building on current activities initiated during its first decade, the Center will focus on research, research training, dissemination, and partnership goals.

Thematic areas of research focus will include technologies for global cancer control, global cancer implementation science, global cancer health disparities, cancer clinical trials in LMICs, and understanding cancer etiology and biology through global collaborations.

Table. Key Elements of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Center for Global Health Strategic Plan for 2021–2025

In 2020, of the NCI extramural awards totaling just more than $900 million, 13% included international components, representing an increase from 9% for the NCI extramural awards in 2010.

Among 1079 extramural awards involving non-US countries in 2020, 342 (32%) involved LMICs.

Strategic priorities for the Center for Global Health include increasing the portfolio of NCI extramural funding involving LMIC collaborators, targeting areas for extramural funding based on key scientific gaps in global cancer control, and promoting equity in global cancer research by supporting the independent scientific capacity of LMIC investigators and institutions.

Examples of recent programs aligned with these strategic priorities appear in the Table. The NCI intramural program similarly conducted nearly 300 projects with international components in 2020, and the Center continues to support and collaborate with NCI intramural investigators seeking to develop and expand international collaborations.

The Center also continues to coordinate NCI engagement with the broader global cancer research and control community, with specific examples highlighted in the Table.

Such engagement includes the International Cancer Control Partnership, a coalition of member organizations that supports countries as they develop, implement, and evaluate data-driven national cancer control plans.

These engagements also include coordinating activities across cancer research funders worldwide through the International Cancer Research Partnership and the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases, and supporting growth of global oncology at NCI-designated cancer centers, nearly half of which (33 of 67) now have formal global oncology programs.

It also includes serving as a WHO Collaborating Center for Global Cancer Control to provide scientific support to recent WHO initiatives focused on cervical, breast, and childhood cancers globally.

By carrying out an ambitious global health agenda oriented around these programmatic goals and scientific themes, the NCI can work with the global research community to significantly accelerate new discoveries for global cancer control, while promoting dissemination of currently available tools.

Efforts to expand and diversify the cancer research workforce will also extend to LMIC investigators and institutions, so they are well equipped to answer questions that are important locally and globally.

As a global cancer research and control community, this vision and the dedicated efforts to reduce cancer morbidity and mortality worldwide must become an urgent postpandemic priority.

Article Information

Corresponding Author: Satish Gopal, MD, National Cancer Institute, 9609 Medical Center Dr, Room 3W62, Rockville, MD 20850

Published Online: August 6, 2021. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.12778

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Drs Gopal and Sharpless reported being employed by the US National Cancer Institute. No other disclosures were reported.

Additional Contributions: We thank Peter Garrett, AB, Patti Gravitt, PhD, Pat Loehrer, MD, Doug Lowy, MD, and Kelli Marciel, MA, for their uncompensated review and comments.

References

See original publication

Originally published at : https://jamanetwork.com