The New York Times

December, 2021

When the Covid-19 pandemic emerged in early 2020, biomedical researchers scrambled to find treatments and drugs that could save the lives of people infected with the coronavirus.

Some of these investigations have been clear successes, leading to millions of saved lives.

Some are still ongoing, having yet to yield strong evidence of effectiveness. Other drugs and treatments have failed the test of science and have been abandoned.

Meanwhile, fake claims and pseudoscience have promoted bogus cures.

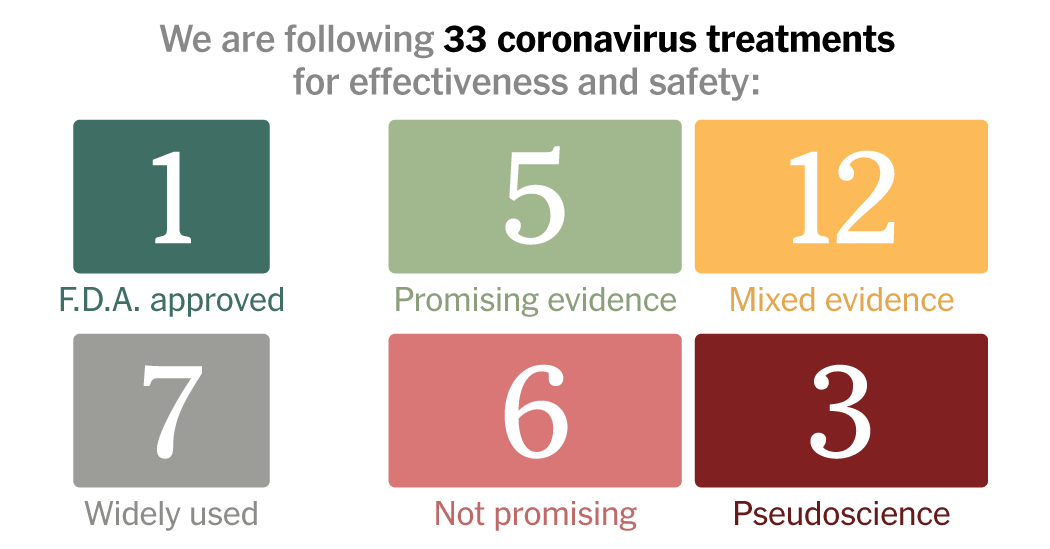

Below is an updated list of 33 of the most talked-about drugs and treatments for Covid-19.

For each entry, we review the evidence for or against its use, based on published scientific findings and consultation with experts.

This list provides a snapshot of the latest research on the coronavirus, but does not constitute medical endorsements.

Always consult your doctor about treatments for Covid-19. You can also consult the Covid-19 Treatment Guidelines from the National Institutes of Health and the World Health Organization’s “living guideline” for Covid-19 drugs. Both of these documents are regularly updated based on new research.

For the current status of vaccine development, see our Coronavirus Vaccine Tracker.

New additions and recent updates

Nov. 16

Pfizer asks the F.D.A. to authorize its Paxlovid pill for emergency use.

Nov. 10

Pfizer’s Paxlovid moves to “promising evidence.”

Nov. 4

The United Kingdom is the first country to authorize molnupiravir for emergency use.

Oct. 26

Expanded monoclonal antibodies and antivirals into their own sections.

Oct. 11

Merck applies for emergency authorization for molnupiravir.

Oct. 1

A trial showed molnupiravir reduced the risk of hospitalization and death by half.

This list provides a snapshot of the latest research on the coronavirus, but does not constitute medical endorsements. Always consult your doctor about treatments for Covid-19.

What the Labels Mean

WIDELY USED: These treatments have gained strong endorsements from medical organizations for Covid-19 patients or are already used widely by doctors and nurses to treat patients hospitalized for many diseases that affect the respiratory system.

PROMISING EVIDENCE: Early evidence from studies on patients suggests effectiveness, but more research is needed. This category includes treatments that have shown improvements in morbidity, mortality and recovery in at least one randomized controlled trial, in which some people get a treatment and others get a placebo.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE: Some treatments show promising results in cells or animals, which need to be confirmed in people. Others have yielded encouraging results in retrospective studies in humans, which look at existing data rather than starting a new trial. Some treatments have produced different results in different experiments, raising the need for larger, more rigorously designed studies to clear up the confusion.

NOT PROMISING: Early evidence suggests that these treatments do not work.

PSEUDOSCIENCE OR FRAUD: These are not treatments that researchers have ever considered using for Covid-19. Experts have warned against trying them, because they do not help against the disease and can instead be dangerous. Some people have even been arrested for their false promises of a Covid-19 cure.

EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS or HUMANS: These labels indicate where the evidence for a treatment comes from. Researchers often start out with experiments on cells and then move onto animals. Many of those animal experiments often fail; if they don’t, researchers may consider moving on to research on humans, such as retrospective studies or randomized clinical trials. In some cases, scientists are testing out treatments that were developed for other diseases, allowing them to move directly to human trials for Covid-19.

Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies can attack the coronavirus and prevent it from invading cells. Several formulations have proven highly effective in the early stages of Covid-19.

WIDELY USED EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

REGEN-COV

The New York-based company Regeneron earned emergency use authorization for its monoclonal antibodies in November 2020. To create their drug, now known as REGEN-COV, Regeneron researchers examined some of the many different kinds of antibodies produced by people who successfully recovered from Covid-19 and from immunized, genetically modified mice. They isolated two very potent antibodies, which they named casirivimab and imdevimab. Regeneron then engineered cells with the genes for these antibodies, and then began making them in large quantities.

The United States government provided Regeneron with support to run clinical trials over the summer. When President Trump was diagnosed with Covid-19 in October, he received a dose of REGEN-COV through the company’s compassionate use program. Trump later claimed that the drug cured him, although it is impossible to know exactly what benefit it provided. For one thing, he also received a number of other treatments at the same time, including remdesivir and dexamethasone. The following month, the F.D.A. authorized REGEN-COV for patients with mild to moderate cases who are at high risk of progressing to serious Covid-19.

Researchers have continued to run clinical trials on REGEN-COV since its authorization, which have given them a better sense of its effectiveness. REGEN-COV is one of three monoclonal antibody drugs that the National Institutes of Health recommends for people who have mild to moderate Covid-19 and are at high risk of serious disease.

Regeneron went on to run a trial to see if REGEN-COV could prevent people from getting sick to begin with. They gave the drug to people who were exposed to the coronavirus in their household.

The researchers found that the treatment reduced the risk of symptomatic infection by 81%. On July 30, 2021, the F.D.A. authorized REGEN-COV for the prevention of Covid-19 in people exposed to the virus.

WIDELY USED EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Bamlanivimab and etesevimab

Eli Lilly won emergency use authorization for its monoclonal antibody, known as bamlanivimab, in November 2020. But the Infectious Disease Society quickly warned against using it, questioning the evidence that the drug was safe and effective. In April 2021, the F.D.A. revoked the E.U.A., because bamlanivimab proved ineffective against coronavirus variants that were growing common in the United States.

Meanwhile, the company also developed a second monoclonal antibody, called etesevimab. The combination of the company’s two drugs offered a 70 percent reduction in hospitalizations and deaths, leading to an E.U.A. for the cocktail in February 2021. In the summer of 2021, the F.D.A. paused the use of Lilly’s cocktail across the United States because it is ineffective against the Beta and Gamma variants of the coronavirus, which were on the rise at the time. But these variants soon were outcompeted by the Delta variant, against which bamlanivimab and etesevimab work well. The F.D.A. reauthorized the monoclonal antibodies in all states on Sept. 2.

The NIH Covid-19 treatment guidelines now recommend bamlanivimab and etesevimab for non-hospitalized Covid-19 patients who are at a high risk for their symptoms to worsen. They also recommend the cocktail to be administered to high-risk and unvaccinated patients who have been exposed to the virus. When Lilly gave bamlanivimab to 965 healthy residents and staff members at nursing homes, they found it reduced the risk of Covid-19 infections by 80 percent.

WIDELY USED EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Sotrovimab

Developed by GSK and Vir Biotechnology, this antibody drug is designed to linger in the lungs so that it can attack the coronavirus as it enters the body. In a Phase 3 trial of the drug, researchers found that sotrovimab reduced the risk of hospitalization or death by 79%. The European Medical Agency’s Committee for Human Medicinal Products concluded that sotrovimab could be used in high-risk Covid-19 patients on May 21, 2021, clearing the way for European Union member states to approve the drug in the coming months. The F.D.A. authorized its use for mild-to-moderate Covid-19 on May 26. On Nov. 17, the companies announced that their contracts with the United States total approximately $1 billion. The NIH Covid-19 treatment guidelines now recommend the drug for non-hospitalized patients at high risk of worsening symptoms.

Originally, sotrovimab was administered in infusions. On Nov. 12, GSK and Vir announced that it could be injected into muscle like a vaccine and still provide strong protection.

PROMISING EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS

AZD7442

With support from the federal government, AstraZeneca isolated two antibodies that showed a potent response to the coronavirus. They then chemically modified each molecule so that it would last longer in the bodies of patients, providing more protection against Covid-19. The company combined the two antibodies into a single cocktail, called AZD7442, which could be injected into muscle like a vaccine.

In a trial on 5,000 volunteers, AstraZeneca found that AZD7442 cut the chances of getting Covid-19 by 77 percent. The company announced the results of the trial on Aug. 20, 2021, adding that the drug can potentially shield people for a year. That durability would make it especially useful to immunocompromised patients who don’t get much protection from vaccines.

The federal government has an agreement with the company to order up to 700,000 doses of the treatment this year, but it will first need to be authorized. The Biden administration, which still has millions of doses of Regeneron’s drug in the queue, has not yet announced any definite plans to buy AstraZeneca’s treatment.

Mimicking the Immune System

Most people who get Covid-19 successfully fight off the virus with a strong immune response. Drugs might help people who can’t mount an adequate defense.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN CELLS AND HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Convalescent plasma

Early in the pandemic, a number of researchers explored the idea of treating patients with plasma filtered from the blood of people who had recovered from Covid-19. The concept dated back over a century, when doctors used so-called convalescent plasma to treat the flu. Plasma loaded with antibodies against the coronavirus might — in theory — stop the progression of Covid-19. But after a year of research, convalescent plasma has not lived up to those hopes, at least for people who are sick enough with Covid-19 to require hospitalization.

Rather than wait for clinical trials to show whether convalescent plasma worked or not, the Trump administration moved quickly to make it available to thousands of people in an emergency access program. In August, top government scientists reportedly stopped the F.D.A. from giving emergency authorization to convalescent plasma, arguing the evidence was still too weak for such a step. On Aug. 23, President Donald J. Trump announced that the authorization would go ahead anyway.

In the following months, tens of thousands of people received convalescent plasma without evidence from large, randomized clinical trials that it was helping them. Few of them participated in such trials, making it difficult to know if patients who recovered did so thanks to the treatment.

Eventually, researchers managed to launch clinical trials that led to some results. The trials failed to find evidence that convalescent plasma helped people who were already hospitalized and seriously ill. In January, British researchers halted a 10,000-person trial because it was clear that convalescent plasma was not helping patients survive. In March, the National Institutes of Health halted a study of their own on patients who came to emergency rooms with mild to moderate symptoms.

Even if convalescent plasma might not work for people sick enough to be hospitalized, there was still a possibility that it might help people earlier in a Covid-19 infection. But trials have failed to deliver strong evidence of such a benefit. On Jan. 6, clinical trial involving 160 recently infected older people in Argentina found that convalescent plasma could reduce people’s chances of severe disease. But a larger study, published in September, on over 1800 patients, did not find that convalescent plasma reduced the risk that hospitalized patients would have to be intubated or that they would die of Covid-19. Patients who got plasma from one blood supplier, the researchers found, had worse outcomes than those who got the standard of care for Covid-19.

On Feb. 4, 2021, the FDA narrowed the permitted use of convalescent plasma under its authorization. Only plasma with a high concentration of antibodies can be used. Additionally, the FDA limited its use to hospitalized patients who are early in the course of their disease, as well as people who cannot make their own supply of antibodies. The Infectious Disease Society of America recommends against using convalescent plasma in hospitals and said there’s no evidence yet supporting its use in people early in their infection.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS

Interferons

Interferons are molecules our cells naturally produce in response to viruses. They have profound effects on the immune system, rousing it to attack the invaders, while also reining it in to avoid damaging the body’s own tissues. Injecting synthetic interferons is now a standard treatment for a number of immune disorders. Rebif, for example, is prescribed for multiple sclerosis.

As part of its strategy to attack our bodies, the coronavirus appears to tamp down interferon. That finding has encouraged researchers to see whether a boost of interferon might help people weather Covid-19, particularly early in infection. Early studies, including experiments in cells and mice, have yielded encouraging results that have led to clinical trials.

On July 20, the British pharmaceutical company Synairgen announced that an inhaled form of interferon called SNG001 lowered the risk of severe Covid-19 in infected patients in a small clinical trial. They later published the details of the study in a medical journal, and in February SNG001 was given to participants in a large, ongoing clinical trial run by the National Institute of Health. On Oct. 20, Synairgen announced that the drug was advancing into a Phase 3 trial in mild to moderate COVID-19 patients.

Last August, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases launched a Phase III trial on Rebif — the drug used for multiple sclerosis — combined with the antiviral remdesivir. The trial is completed, but the results have yet to be made public.

Antivirals

Antivirals can stop viruses such as H.I.V. and hepatitis C from hijacking our cells. Scientists are searching for antivirals that work against the new coronavirus. One is now approved for Covid-19, and two others have shown promising results in Phase 3 clinical trials.

WIDELY USED F.D.A. APPROVED EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS

Remdesivir

Remdesivir, made by Gilead Sciences under the brand Veklury, is the first — and so far only — drug to gain full approval from the F.D.A. for the treatment of Covid-19. Gilead succeeded in launching clinical trials early in the pandemic, and their results were encouraging. With few other options to choose from, remdesivir went into widespread use after its approval in October 2020. Since then, however, scientists have raised questions about how firm the results of these trials were, and about how widely remdesivir should be prescribed. And in the time since remdesivir’s approval, other drugs, such as monoclonal antibodies and new antivirals, have emerged with the potential to be easier to give to patients and more effective against Covid-19.

Remdesivir was originally tested as an antiviral against Ebola and Hepatitis C. The molecular stops viruses by inserting itself into their genes, creating mutations that leave the viruses unable to replicate. While remedesivir worked against viruses in dishes of cells, clinical trials delivered lackluster results.

Nevertheless, Gilead decided to try it out on coronaviruses when the Covid-19 pandemic emerged. After promising results on cells, a large clinical trial was then launched, which found that the drug reduced the recovery time of people hospitalized with Covid-19 from 15 to 11 days.

The F.D.A. responded quickly to this data in May 2020 by issuing an emergency authorization for remdesivir’s use in critically ill patients who need supplemental oxygen. In August, they expanded that approval after another study found that patients with less severe forms of Covid-19 seemed to benefit modestly from a five-day treatment course of remdesivir. The revised approval permitted the use of the drug on all patients hospitalized with Covid-19, regardless of how severe their disease is. The move was criticized by some experts who said the F.D.A. had expanded remdesivir’s use without enough strong evidence to back the change.

When former President Trump developed Covid-19 in October he received a five-day course of remdesivir. The F.D.A. gave full approval to the drug soon afterwards, on Oct. 22, for use in patients 12 years and older. The regulatory success was immensely lucrative for Gilead, which made $2.8 billion on remdesivir in 2020 alone.

Yet many experts grew skeptical of remdesivir’s benefits. For one thing, the initial trials failed to show statistically significant evidence that remdesivir actually prevents deaths from Covid-19. The World Health Organization fueled more skepticism when they published a global randomized trial that found remdesivir had little or no effect on the length of hospitalization, the risk of going onto a ventilator, or overall mortality.

In the wake of these results, the WHO issued guidelines recommending against using remdesivir. The National Institutes of Health only suggests using remdesivir with patients who are hospitalized and requiring oxygen. They recommend against starting severely ill patients on a course of the drug.

PROMISING EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Molnupiravir

Molnupiravir (also known as MK-4482 and previously as EIDD-2801) is an antiviral originally designed to fight the flu. Ridgeback Biotherapeutics and Merck are collaborating to develop it as a treatment for Covid-19. Unlike remdesivir, which has to be given intravenously, molnupiravir can be swallowed as a pill. That could make it easier to use as a means to stop the disease early in its progression.

In early studies in human lung cells and on animals molnupiravir produced promising results against the new coronavirus. In October 2020, the companies started two Phase 2/3 trials to see if it could reduce mortality and speed recovery in patients.

In April, Merck and Ridgeback announced that it would end their trial of molnupiravir in hospitalized patients because the data showed it was unlikely to help. But in October 2021, they announced that a trial on high-risk outpatients had delivered promising results. In an initial study, Molnupiravir reduced the risk of hospitalization and death by half. But a complete analysis of the trial later reduced its effectiveness to 30 percent. The F.D.A. will host a public meeting to review Merck’s application for an emergency authorization at the end of November. The federal government has now committed to purchase a total of approximately 3.1 million courses of molnupiravir, for approximately $2.2 billion.

On Nov. 4, the United Kingdom became the first country to grant emergency authorization for the use of molnupiravir. Adults with mild-to-moderate Covid-19 that have at least one risk factor for developing severe illness are now eligible to receive the drug.

PROMISING EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS

Paxlovid (also known as PF-07321332)

Pfizer developed a drug in the early 2000s as a potential treatment for SARS, which is caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV. At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, they retooled it to work against SARS-CoV-2, which has a similar biology. In addition, they modified the drug, originally designed to be given intravenously, as a pill. When mice were given the drug orally, it reached high enough levels in the body to block the coronavirus. Paxlovid, as the drug is now known, went into clinical trials in March 2021, followed by a larger Phase 3 trial in July.

In November, Pfizer announced that Paxlovid cut the risk of hospitalization or death by 89 percent when given within three days after the start of symptoms. They have yet to make the detailed results of the trial public. On Nov. 16, Pfizer announced it had applied to the Food and Drug Administration to authorize Paxlovid for emergency use. If the F.D.A. authorized the drug, it could become available to high-risk patients within a few months. Pfizer announced a $5.3 billion supply deal with the United States on Nov. 18. The agreement will provide the country with as many as 10 million courses of the drug.

In September, false claims circulated on social media that people who took the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine would have to take Pfizer’s antiviral drug twice a day. The vaccine is highly effective at preventing infections and severe disease. Paxlovid is an entirely separate drug, which blocks the virus from replicating inside cells.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS

Favipiravir (also known as Avigan)

Originally designed to beat back influenza, favipiravir blocks a virus’s ability to copy its genetic material. Some small studies suggested that the drug might clear the coronavirus from the airway, leading to a number of countries, including Japan, Kenya, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Thailand, to approve favipiravir for Covid-19. But these decisions may have been too hasty; the evidence from clinical trials has proven disappointing. The quality of many of the studies has been very low, either because they only recruited small numbers of patients or were not randomized enough. The Canadian company Appili Therapeutics ran a Phase 3 trial in which they gave the drug to 1,231 newly diagnosed volunteers. In November 2021 the company announced that favipiravir did not speed up recovery from Covid-19.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN CELLS AND ANIMALS

Recombinant ACE-2

To enter cells, the coronavirus must first unlock them — a feat it accomplishes by latching onto a human protein called ACE-2. Scientists have created artificial ACE-2 proteins which might be able to act as decoys, luring the coronavirus away from vulnerable cells. Recombinant ACE-2 proteins have shown promising results against Covid-19 in experiments on cells and animals, and preliminary clinical trials suggest that they are safe for people. Their effectiveness is now being tested in large-scale trials.

NOT PROMISING EVIDENCE IN CELLS AND HUMANS

Ivermectin

For decades, ivermectin has served as a potent drug to treat parasitic worms. Doctors use it against river blindness and other diseases, while veterinarians give dogs a different formulation to prevent heartworm. Studies on cells have suggested ivermectin might also kill viruses. But scientists have yet to find strong evidence in animal studies or human trials that it can treat viral diseases. As a result, ivermectin is not approved to use as an antiviral.

Last April, Australian researchers reported that the drug blocked coronaviruses in cell cultures. But they used a dosage that was so high it might have dangerous side effects in people. The F.D.A. immediately issued a warning against taking pet medications that contain ivermectin. “These animal drugs can cause serious harm in people,” the agency warned. On March 5, 2021, the F.D.A. issued another warning not to use ivermectin to treat or prevent Covid-19. The European Medicines Agency released a similar warning later that month.

Nevertheless, ivermectin gained widespread popularity as a supposed treatment for Covid-19. In the United States, the Senate held a committee hearing in December where a doctor extolled ivermectin as a “effectively a ‘miracle drug’ against Covid-19.” But those claims were not backed up by clear results from large, randomized clinical trials.

A number of small clinical trials have been carried out to test ivermectin against Covid-19. In July 2021, a team of researchers reviewed the studies conducted up until then. “We found no evidence to support the use of ivermectin for treating or preventing COVID-19 infection, but the evidence base is limited,” they concluded. One high-profile study that seemed to show ivermectin was highly effective was removed from a preprint website because of concerns about serious flaws in the research.

A number of large-scale randomized clinical trials are underway that may provide a clearer picture. In August, the National Institutes of Health began testing the drug on people 30 years old or older who test positive for Covid-19 within the previous ten days and have at least two symptoms for a week or less. Shortly before that study launched, another trial on 1500 patients found no benefit from ivermectin.

NOT PROMISING EVIDENCE IN CELLS

Oleandrin

Oleandrin is a compound produced by the oleander shrub. Last May the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases tested oleandrin on coronavirus-infected cells last May but the experiments were inconclusive. Researchers at Phoenix Biotechnology, a San-Antonio based company, and the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston then released a study finding that it was effective in a culture of monkey kidney cells infected with the coronavirus. The study has not yet been published in a scientific journal.

Oleandrin first came to fame last July when Mike Lindell — the chief executive of My Pillow, a donor to President Trump, and a Phoenix Biotechnology investor — talked to the former president about the compound at a White House meeting. In November, it made the news once more when former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson contracted Covid-19. Dr. Carson, a former neurosurgeon, told the Washington Post that he took oleandrin, having heard about it from Mr. Lindell. He claimed that he felt better just five hours after taking it. However, CNN later reported that in a Nov. 19 Facebook post, Dr. Carson said he also received monoclonal antibodies, which he credited for his recovery. There is still no evidence that oleandrin is safe and effective for Covid-19, and the FDA has not approved it to treat the disease.

NOT PROMISING EVIDENCE IN CELLS AND HUMANS

Lopinavir and ritonavir

Twenty years ago, the F.D.A. approved this combination of drugs to treat H.I.V. Researchers found that they also stop the coronavirus from replicating in cultures of cells. But subsequent clinical trials in patients proved disappointing. In early July, the World Health Organization suspended trials on patients hospitalized for Covid-19. They didn’t rule out studies to see if the drugs could help patients not sick enough to be hospitalized, or to prevent people exposed to the new coronavirus from falling ill. The N.I.H. Covid treatment guidelines recommend against using lopinavir and ritonavir in both hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. The drug could also still have a role to play in certain combination treatments.

NOT PROMISING EVIDENCE IN CELLS, ANIMALS AND HUMANS

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine

German chemists synthesized chloroquine in the 1930s as a drug against malaria. A less toxic version, called hydroxychloroquine, was invented in 1946, and later was approved for other diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers discovered that both drugs could stop the coronavirus from replicating in cells. But after a year of high hopes and intense research, the scientific consensus emerged that the drug is not helpful for Covid-19 and may cause harmful side effects.

In addition to the studies on cells, a few small studies on patients in early 2020 offered some hope that hydroxychloroquine could treat Covid-19. Former President Trump soon promoted hydroxychloroquine at press conferences, touting it as a “game changer,” and said he took it himself. The F.D.A. temporarily granted hydroxychloroquine emergency authorization for use in Covid-19 patients — which a whistleblower later claimed was the result of political pressure. In the wake of the drug’s newfound publicity, demand spiked, resulting in shortages for people who rely on hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for other diseases.

Once scientists got results from tests on animals and humans, however, the drugs proved disappointing. Experiments on animals such as monkeys and mice found no evidence that hydroxychloroquine stopped the disease. Randomized clinical trials found that hydroxychloroquine didn’t help people with Covid-19 get better or prevent healthy people from contracting the coronavirus. The World Health Organization, the National Institutes of Health and Novartis halted trials investigating hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for Covid-19, and the F.D.A. revoked its emergency approval. The F.D.A. now warns that the drug can cause a host of serious side effects to the heart and other organs when used to treat Covid-19. On March 2, an expert panel at the World Health Organization strongly recommended against the use of hydroxychloroquine in all patients, adding that the drug is no longer a research priority.

Putting Out Friendly Fire

The most severe symptoms of Covid-19 are the result of the immune system’s overreaction to the virus. Scientists are testing drugs that can rein in its attack.

WIDELY USED EVIDENCE IN HUMANS

Dexamethasone

As doctors began treating Covid-19 patients in early 2020, they observed that some patients developed inflammation in their lungs that became so devastating that it could lead to death. British researchers began randomized clinical trials of anti-inflammatory drugs to see if any of them could save lives. In one trial, they tested a cheap, safe drug called dexamethasone. In June 2020, they reported that dexamethasone reduced Covid-19 deaths. A study of more than 6,000 people found that dexamethasone reduced deaths by one-third in patients on ventilators, and by one-fifth in patients on oxygen. It may be less likely to help — and may even harm — patients who are at an earlier stage of Covid-19 infections, however. In its Covid-19 treatment guidelines, the National Institutes of Health recommends only using dexamethasone in patients with Covid-19 who are on a ventilator or are receiving supplemental oxygen.

In September, researchers reviewed the results of trials on dexamethasone, along with two other steroids, hydrocortisone and methylprednisolone. Overall, they concluded, steroids were linked with a one-third reduction in deaths among Covid-19 patients.

The results of the trial led to the widespread use of dexamethasone on seriously ill patients. In a March 2021 analysis, the British government estimated that the drug has saved a million lives worldwide.

PROMISING EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Baricitinib

Baricitinib, sold under the brand name Olumiant, is an anti-inflammatory drug for rheumatoid arthritis. It reduces inflammation by blocking an immune system protein called interleukin-6. In clinical trials, people with advanced Covid-19 who received baricitinib benefited from the drug. The F.D.A. gave it emergency use authorization on July 29, 2021. In its Covid-19 guidelines, the National Institutes of Health recommends baricitinib for hospitalized patients who are sick enough to require oxygen delivered through a high-flow device or noninvasive ventilation.

PROMISING EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab, sold under the brand name Actemra, is another arthritis drug that works by blocking interleukin-6. An analysis of clinical trials showed that it could reduce mortality from Covid-19. In June 2021, the F.D.A. gave tocilizumab emergency authorization for some hospitalized patients with Covid-19. The World Health Organization recommends tocilizumab for people with severe disease. Alternatively, they recommend that patients be treated with a similar arthritis drug called sarilumab, sold under the brand name Kevzara.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS

Fluvoxamine

While baricitinib and tocilizumab have long been used to treat inflammation, drugs used to treat other conditions are also showing some promise to tamp down runaway immune responses. Fluvoxamine, for example, is a cheap drug that has long been used to treat depression. But in 2019, researchers found that fluvoxamine can reduce inflammation in mice. When the pandemic arose, researchers tried repurposing fluvoxamine to treat Covid-19.

In November 2020, a team of doctors published a small randomized clinical trial on the effect of fluvoxamine given to people soon after they were diagnosed with Covid-19. While 8.3 percent of the patients who got a placebo had to be hospitalized, none of the people who got the drug deteriorated. In a larger clinical trial in Brazil, researchers gave 738 randomly selected Covid-19 patients fluvoxamine, while another 733 received a placebo. On Oct. 28, 2021, the researchers published the results in the journal Lancet Global Health. They found that the drug reduced the need for hospitalization or prolonged medical observation by one-third. The N.I.H. guidelines for Covid-19, which do not recommend fluvoxamine, have yet to be updated in light of the latest results.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS

Lenzilumab

The drug lenzilumab is an antibody that’s been designed to latch onto a signalling molecule that triggers runaway inflammation. In May 2021, researchers published the results of a Phase 3 trial of lenzilumab, in which 261 people with Covid-19 got the drug while 259 got a placebo. All of the subjects had low levels of oxygen but were not yet on a ventilator. The study, which has not yet been published in a scientific journal, found that the drug reduced the chances that patients under 85 who had not yet developed a cytokine storm went on a ventilator or died. Humanigen, the company that makes lenzilumab, applied for an emergency use authorization. On Sept. 9, they announced that the F.D.A. declined its request. The company may try again if new data from the drug’s ongoing trials prove more encouraging.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS

EXO-CD24

Researchers in Israel ran a small pilot study on a drug called EXO-CD24 to see if it could tamp down inflammation from Covid-19. In February 2021, they announced that 31 out of 35 hospitalized patients were discharged after three to five days of treatment with the drug. But it was impossible to know if the drug helped them, because the trial was not large, blinded, or placebo-controlled. Nor have these preliminary results been published in a journal or posted online.

Nevertheless, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called EXO-CD24 a “miracle drug.” In March, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro announced that his administration intended to sign a memorandum of understanding to test a nasal spray version of EXO-CD24, which he said could emerge as “the real solution to treating Covid.”

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS

Leronlimab

The drug leronlimab is an antibody that was originally tested as a way to treat H.I.V. It latches onto a protein on the surface of cells called CCR5, which the virus normally uses to gain entry into them. Normally, CCR5 plays a role in relaying cytokine signals, which raised the possibility that leronlimab might be able to weaken cytokine storms triggered by Covid-19. A Washington-based company called CytoDyn began running studies to explore its use. Small studies yielded encouraging results, which were then followed by larger clinical trials. In March 2021, CytoDyn portrayed the results of the trials as positive. “The Company believes this new information bolsters the case for immediate use of leronlimab for critically ill patients,” the president of CytoDyn said in the company’s press release.

But on May 17, the F.D.A. took the extraordinary step of pushing back against CytoDyn’s claims. Zeroing in on small subgroups might give the impression that leronlimab was effective, the regulators said, but the overall evidence failed to do so. “It has become clear that the data currently available do not support the clinical benefit of leronlimab for the treatment of Covid-19,” the F.D.A. said in its statement.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS

Stem cells

Certain kinds of stem cells can secrete anti-inflammatory molecules. Over the years, researchers have tried to use them as a treatment for cytokine storms, and now dozens of clinical trials are under way to see if they can help patients with Covid-19. But these stem cell treatments haven’t worked well in the past, and it’s not clear yet if they’ll work against the coronavirus. The N.I.H.’s Covid-19 treatment guidelines recommend against the use of mesenchymal stem cells for Covid-19, except in a clinical trial, while the FDA has issued warnings that unproven stem cells treatments can potentially harm patients. One company, Mesoblast, had begun a late-stage clinical trial to test whether a stem cell treatment could curb the death rate among Covid-19 patients. But an independent board of researchers advising the trial has now recommended that the trial stop enrolling, and announced that the trial is unlikely to meet its original goal.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Colchicine

In ancient Greece, people who suffered from gout treated their pain by chewing the bulbs of the autumn crocus. In the nineteenth century, chemists isolated the compound colchicine from the flower, which was prescribed by doctors for a number of ailments. In 2009 the FDA approved colchicine to relieve the inflammation from gout and other disorders. And when the role of inflammation in Covid-19 became clear, researchers began investigating colchicine as a potential treatment.

After a series of small trials, researchers in Canada ran a randomized controlled trial on 4500 people, treating them with colchicine shortly after a diagnosis with Covid-19. The researchers posted the study online on Jan. 27 in advance of publication in a medical journal. The results suggested colchicine might provide a modest reduction in hospitalization for patients, but outside experts have questioned whether outcomes were just the result of chance.

Last November, British researchers launched a large-scale randomized clinical trial of colchicine on patients hospitalized with Covid-19. On March 5, they closed the trial down because people taking colchicine were just as likely to die as people receiving a placebo.

Research on colchicine is continuing, however. In March 2021 another large-scale trial on people with early Covid-19 was launched in the United Kingdom.

NOT PROMISING EVIDENCE IN HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Blood filtration systems

In 2020, the F.D.A. granted emergency use authorization to several devices that filter cytokines from the blood in an attempt to cool cytokine storms. But since then, none have demonstrated that they are safe and effective for Covid-19 in randomized, controlled trials. In May 2021, for example, researchers published a trial that found no benefit in using an authorized device called Cytosorb. on hospitalized patients. In fact, more people who got the treatment died than the ones who didn’t. Some researchers have warned that some blood filtration systems may cause risks by removing beneficial components of blood such as vitamins or medications. In a September 2020 commentary, a team of experts urged that doctors avoid using blood filtration for the regular treatment of Covid-19, arguing that it is only appropriate for now in clinical trials.

NOT PROMISING EVIDENCE IN HUMANS EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Azithromycin

Azithromycin is an antibiotic normally used to fight bacterial infections. But researchers have observed that the drug can also lessen inflammation. That feature made azithromycin attractive to doctors looking for a potential treatment for Covid-19 that was already known to be safe. Making the drug even more enticing was preliminary evidence that it could block the coronaviruses in test tubes. But in December, a large-scale randomized clinical trial found no benefit of azithromycin in patients hospitalized with Covid-19.

Other Treatments

Other supportive treatments to help patients with Covid-19.

WIDELY USED

Prone positioning

Health workers have long known that the simple act of flipping hospital patients who are in severe respiratory distress onto their bellies can open up their lungs. The maneuver has become commonplace in hospitals around the world since the start of the pandemic. It might help some individuals avoid the need for ventilators entirely. But clinical trials on Covid-19 patients have proved disappointing so far. In November 2021, a team of researchers reported the results of a randomized trial with 248 patients who were hospitalized but not yet ventilated. They failed to find a benefit to proning.

WIDELY USED EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION

Ventilators and other respiratory support devices

Devices that help people breathe are an essential tool in the fight against deadly respiratory illnesses. Some patients do well if they get an extra supply of oxygen through the nose or via a mask connected to an oxygen machine. Patients in severe respiratory distress may need to have a ventilator breathe for them until their lungs heal. Doctors are divided about how long to treat patients with noninvasive oxygen before deciding whether or not they need a ventilator. Not all Covid-19 patients who go on ventilators survive, but the devices are thought to be lifesaving in many cases.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS

Anticoagulants

Anticoagulants and other antithrombotic drugs are commonly given to patients with a wide range of diseases that raise their risks of developing blood clots. In 2020, researchers found that the coronavirus can invade the lining of blood vessels and the formation of clots with the potential for serious harm. That discovery led to a number of trials to see if giving Covid-19 patients a higher dose of anticoagulants, or other blood thinning agents, improved their odds of recovery.

So far, the results have been mixed. Two large studies reported in March 2021 — one on 600 patients in Iran, and the other on over 1,000 patients globally — did not find that increased doses of anticoagulants improved the outcome of Covid-19 in patients admitted to the ICU. And in one Brazilian study, which was published in June 2021, researchers found that anticoagulant drug rivaroxaban did not improve clinical outcomes and even led to more bleeding. On the other hand, three large clinical trials found promising evidence that blood thinners reduced the chances that moderately ill patients hospitalized for COVID-19 needed ventilation. More trials are still underway, including many on aspirin, which is known to act as a blood thinner. But in June 2021, a large-scale randomized clinical trial found that aspirin had no significant impact on patient mortality. In sicker patients, clot buster drugs are being tested in the hope of helping combat respiratory failure.

TENTATIVE OR MIXED EVIDENCE EVIDENCE IN HUMANS

Vitamin and mineral supplements

Our bodies need vitamins and minerals to work properly. Some researchers are investigating whether supplements might help against Covid-19, but there’s no strong evidence yet that they prevent infections or speed up recovery from them.

One vitamin that has attracted a great deal of attention is Vitamin D. When former President Trump was hospitalized for Covid-19, Vitamin D was part of the treatment he received from his doctors. Vitamin D is important to our health, promoting good bone health and helping immune cells function. Some studies have found an association between low levels of vitamin D and higher rates of Covid-19. But such studies cannot establish that this deficiency was the cause of those disease rates. It may be that populations who suffer high rates of vitamin D deficiency are getting hit harder by the coronavirus for other reasons, including poorer access to health care or underlying conditions like obesity. Some clinical trials have failed to find a benefit to Covid-19 patients from Vitamin D. But others are still underway. Still, N.I.H. treatment guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to recommend Vitamin D against the disease.

In addition to Vitamin D, Trump also received zinc. This mineral helps proteins throughout the body function, and people with zinc deficiencies are at higher risk of getting sick with infectious diseases. A 2010 study on the coronavirus that causes SARS found that zinc can put the brakes on the replication of the virus in cells. In February, researchers at the Cleveland Clinic published a randomized clinical trial that found no benefit from zinc. The same trial also failed to find any help from Vitamin C.

Pseudoscience and Fraud

False claims about Covid-19 cures abound. The F.D.A. maintains a list of almost 200 fraudulent Covid-19 products, and the W.H.O. debunks many myths about the disease.

WARNING: DO NOT DO THIS

Drinking or injecting bleach and disinfectants

Disinfectants can help slow the spread of the coronavirus, but only when used properly. The CDC offers guidelines for cleaning your house and hands. Washing with soap is the best way to keep your hands clean, but alcohol-based sanitizers will do if you’re not near a sink.

It’s important to only use the right products. Never mix bleach and ammonia to disinfect surfaces, for example, because it can release toxic gas. As for hand-sanitizers, make sure to use brands with greater than 60% ethanol or 70% isopropanol. The FDA has warned that some sanitizers contain wood alcohol, or methanol, which can be dangerous.

Last April, former President Trump suggested that disinfectants such as alcohol or bleach might be effective against the coronavirus if directly injected into the body. His comments were immediately refuted by health professionals and researchers around the world — as well as the makers of Lysol and Clorox. In July, Federal prosecutors charged four Florida men with marketing bleach as a cure for COVID-19. The following month, they were arrested in Colombia.

WARNING: NO EVIDENCE

UV light

President Trump also speculated at an April press conference about hitting the body with “ultraviolet or just very powerful light.” Researchers have used UV light to sterilize surfaces, including killing viruses, in carefully managed laboratories. But UV light would not be able to purge the virus from within a sick persons’ body. This kind of radiation can also damage the skin. Most skin cancers are a result of exposure to the UV rays naturally present in sunlight.

WARNING: NO EVIDENCE

Silver

In July, Utah resident Gordon Pedersen was indicted for “posing as a medical doctor to sell a baseless treatment for coronavirus.” Mr. Pedersen’s alleged crime was peddling lozenges, lotions and soaps containing silver. Several metals do have natural antimicrobial properties, but none has been shown effective against the coronavirus. As for silver, the National Institutes of Health warns that “scientific evidence doesn’t support the use of colloidal silver dietary supplements for any disease or condition.” It can also be dangerous, causing people’s skin to turn blue and making it difficult for them to absorb antibiotics and other drugs.

Mr. Pedersen is not alone. The F.D.A. has threatened legal action against a host of other people claiming silver-based products are safe and effective against Covid-19 — including televangelist Jim Bakker and InfoWars host Alex Jones.

Tracking the Coronavirus

Additional reporting by Rebecca Robbins.

Note: After additional discussions with experts we have adjusted several labels on the tracker.

The “Strong evidence” label has been removed until further research identifies treatments that consistently benefit groups of patients infected by the coronavirus.

In its place, “Promising evidence” will be used for drugs such as remdesivir and dexamethasone that have shown promise in at least one randomized controlled trial, …

… and “Widely used” for treatments such as proning and ventilators that are often used with severely ill patients, including those with Covid-19.

And we may reintroduce the “Ineffective” label when ongoing clinical trials repeatedly end with disappointing results.

Correction: A previous version of the tracker misstated the role of ivermectin in treating heartworm disease in dogs. The drug is used to prevent heartworm; it is not a cure.

Sources:

National Library of Medicine; National Institutes of Health; William Amarquaye, University of South Florida; Paul Bieniasz, Rockefeller University; Jeremy Faust, Brigham & Women’s Hospital; Matt Frieman, University of Maryland School of Medicine; Noah Haber, Stanford University; Harlan Krumholz, Yale School of Medicine; Swapnil Hiremath, University of Ottawa; Akiko Iwasaki, Yale University; Paul Knoepfler, University of California, Davis; Elena Massarotti, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; John Moore and Douglas Nixon, Weill Cornell Medical College; Erica Ollman Saphire, La Jolla Institute for Immunology; Regina Rabinovich, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Ilan Schwartz, University of Alberta; Phyllis Tien, University of California, San Francisco.

Originally published at https://www.nytimes.com on July 16, 2020.