Cancer-killing cells still present 10 years on, with results suggesting therapy is a cure for certain blood cancers

The Guardian

Linda Geddes Science correspondent

February 2, 2022

Doug Olson still has cancer-killing cells 10 years after infusion. Photograph: AP

Two of the first human patients to be treated with a revolutionary therapy that engineers immune cells to target specific types of cancer still possess cancer-killing cells a decade later with no sign of their illness returning.

The finding suggests CAR T-cell therapy constitutes a “cure” for certain blood cancers, although adapting it to treat solid tumours is proving more challenging.

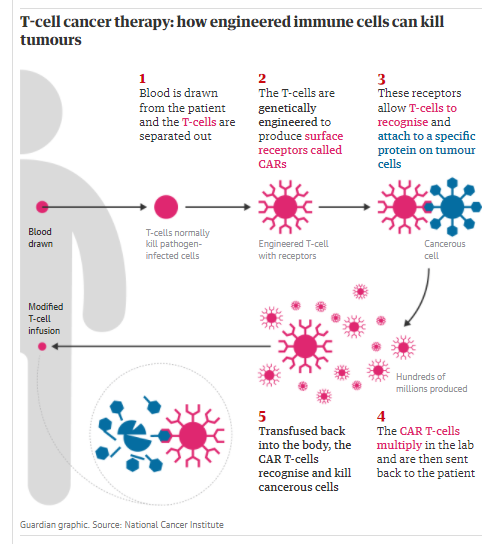

CAR — chimeric antigen receptor — T-cell therapy works by genetically engineering an individual’s T-cells to recognise and destroy cancer cells.

T-cells are a type of white blood cell that can recognise and destroy foreign cells, including cancer cells, but because cancer is very good at evading immune detection, they often miss their mark. CAR T-cells are engineered to make them better at detecting cancer cells.

In the UK the therapy is approved for use in children and young adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) and adults with certain types of lymphoma — both are blood cancers.

In trials, CAR-T therapy has been extraordinarily successful, putting patients into remission who had months to live, but the long-term effects had not been extensively studied.

Now, Prof Carl June, at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and colleagues report in Nature how cells from two of the first patients to be treated are faring 10 years on. Both patients were suffering from chronic lymphocytic leukaemia when they had CAR-T therapy in 2010, and achieved complete remission within months of treatment, meaning all signs and symptoms of their leukaemia disappeared.

They remain cancer-free today. One of the patients, Doug Olson, said he had taken up running half-marathons after his treatment. When the researchers examined the patients’ blood, they could still identify CAR T-cells that were capable of proliferating and killing cancer cells, as well as others that help to shape immune responses.

“We call these cells a living therapy, but it was a big surprise to us that they are still able to kill cancer cells 10 years after infusion,” June said. “We can’t say whether every last cancer cell was gone within three weeks [of treatment], or it could be that they keep coming up like whack-a-mole and then get killed, but we know that these [CAR T-cells] are on patrol. They persist and they are functional.”

Prof Martin Pule, the director of the UCL Cancer Institute CAR T-cell programme, described the paper as a landmark. “A decade ago, CAR T-cell therapy was a therapeutic approach explored by a very small number of scientists and was considered a fringe approach and unlikely to work,” he said. “This paper shows us that CAR T-cells can give patients with cancers which no longer respond to chemotherapy remissions which last a decade.”

Prof David Porter, of the University of Pennsylvania, who was involved in the research, said the team had been unprepared for how successful it would be. “Cancer doctors don’t use words like ‘cure’ lightly or, frankly, very often. But we now have patients like Doug who haven’t relapsed, and we really believe that we can start to use the word ‘cure’.”

A technician works on a research process to find new CAR T-cells at a laboratory in Paris. Photograph: Thomas Coex/AFP/Getty Images

CAR-T therapy does not work for all patients or for all types of cancers. It is also labour-intensive and expensive, although June said the costs would come down.

Pule said: “Solid cancers are harder to treat with CAR T-cells because they surround themselves with proteins and cells which shield them from the immune system. This is called the ‘tumour microenvironment’. We know that CAR T-cells can work well against solid cancer. For example, [we] have shown that they are active against solid cancers like neuroblastoma; however the CAR T-cells are overwhelmed by the microenvironment.”

Second-generation T-cells, engineered to recognise the tumour and resist the microenvironment, are being tested in clinical trials, including one in leukaemia patients at UCL.

Originally published at https://www.theguardian.com on February 2, 2022.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

Decade-long leukaemia remissions with persistence of CD4+ CAR T cells

Nature

J. Joseph Melenhorst, Gregory M. Chen, Carl H. June et al

February 2, 2022

Abstract

The adoptive transfer of T lymphocytes reprogrammed to target tumour cells has demonstrated potential for treatment of various cancers1,2,3,4,5,6,7.

However, little is known about the long-term potential and clonal stability of the infused cells.

Here we studied long-lasting CD19-redirected chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in two patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia1,2,3,4 who achieved a complete remission in 2010.

CAR T cells remained detectable more than ten years after infusion, with sustained remission in both patients.

Notably, a highly activated CD4+ population emerged in both patients, dominating the CAR T cell population at the later time points.

This transition was reflected in the stabilization of the clonal make-up of CAR T cells with a repertoire dominated by a small number of clones.

Single-cell profiling demonstrated that these long-persisting CD4+ CAR T cells exhibited cytotoxic characteristics along with ongoing functional activation and proliferation.

In addition, longitudinal profiling revealed a population of gamma delta CAR T cells that prominently expanded in one patient concomitant with CD8+ CAR T cells during the initial response phase.

Our identification and characterization of these unexpected CAR T cell populations provide novel insight into the CAR T cell characteristics associated with anti-cancer response and long-term remission in leukaemia.