2019 Global Health Security Index (GHS Index)

Credit to the image above: The Lancet

November, 2019

Biological threats-natural, intentional, or accidental-in any country can pose risks to global health, international security, and the worldwide economy. Because infectious diseases know no borders, all countries must prioritize and exercise the capabilities required to prevent, detect, and rapidly respond to public health emergencies. Every country also must be transparent about its capabilities to assure neighbors it can stop an outbreak from becoming an international catastrophe. In turn, global leaders and international organizations bear a collective responsibility for developing and maintaining robust global capability to counter infectious disease threats. This capability includes ensuring that financing is available to fill gaps in epidemic and pandemic preparedness. These steps will save lives and achieve a safer and more secure world.

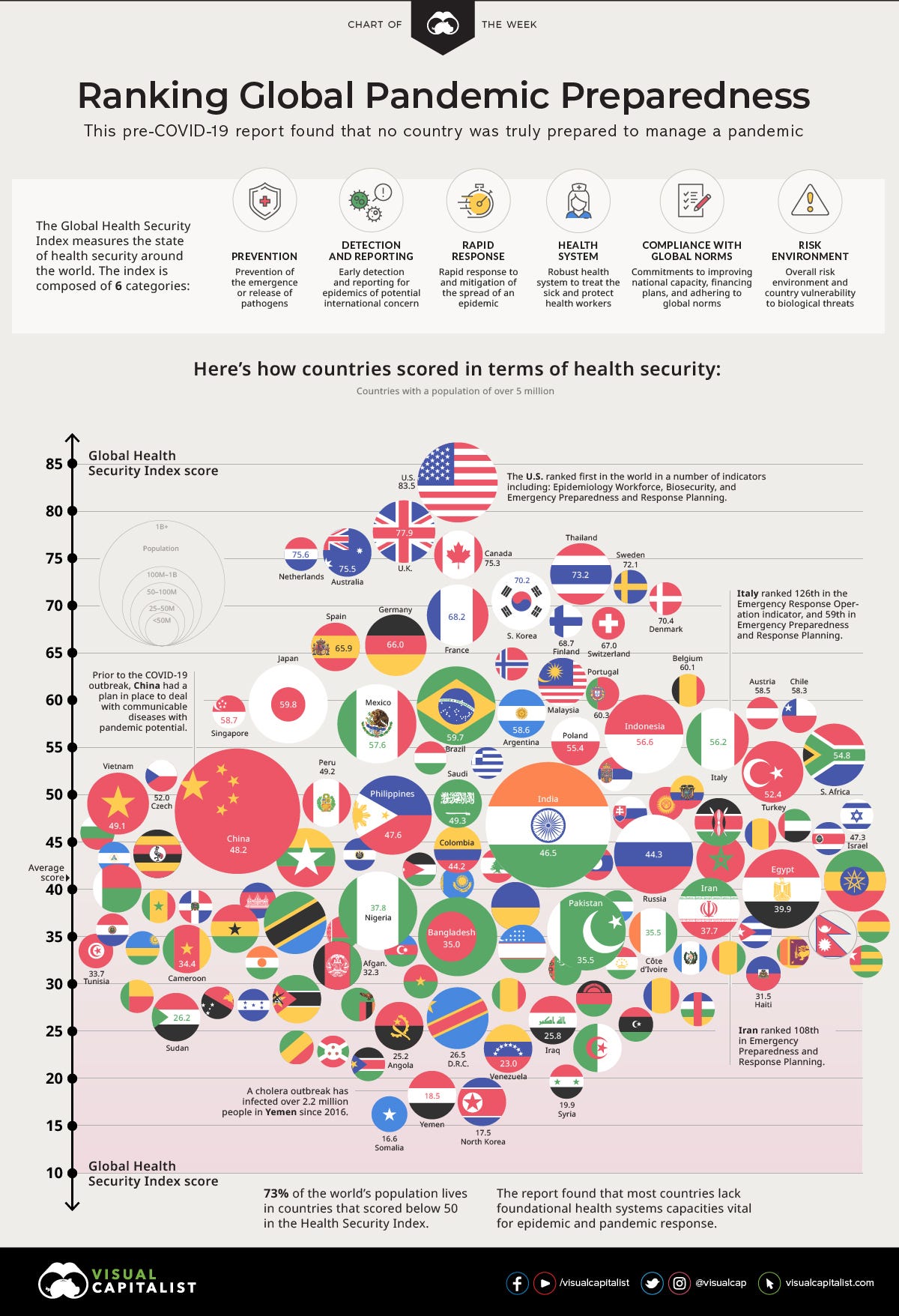

The Global Health Security (GHS) Index is the first comprehensive assessment and benchmarking of health security and related capabilities across the 195 countries that make up the States Parties to the International Health Regulations (IHR [2005]). The GHS Index is a project of the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (JHU) and was developed with The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). These organizations believe that, over time, the GHS Index will spur measurable changes in national health security and improve international capability to address one of the world’s most omnipresent risks: infectious disease outbreaks that can lead to international epidemics and pandemics.

The GHS Index is intended to be a key resource in the face of increasing risks of high-consequence and globally catastrophic biological events and in light of major gaps in international financing for preparedness. These risks are magnified by a rapidly changing and interconnected world; increasing political instability; urbanization; climate change; and rapid technology advances that make it easier, cheaper, and faster to create and engineer pathogens.

Developed with the guidance of an international expert advisory panel, the GHS Index data are drawn from publicly available data sources from individual countries and international organizations, as well as an array of additional sources including published governmental information, data from the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Bank, country legislation and regulations, and academic resources and publications. Unique in the field, the GHS Index provides a comprehensive assessment of countries’ health security and considers the broader context for biological risks within each country, including a country’s geopolitical considerations and health system and whether it has tested its capacities to contain outbreaks.

Knowing the risks, however, is not enough. Political will is needed to protect people from the consequences of epidemics, to take action to save lives, and to build a safer and more secure world.

The report summarizes the results of the first GHS Index, including overall findings about the state of national health security capacity across each of the six GHS Index categories, as well as additional findings specific to functional areas of epidemic and pandemic preparedness. The full report also offers 33 recommendations to address gaps identified by the GHS Index.

Whereas every country has a responsibility to understand, track, improve, and sustain national health security, new and increased global biological risks may require approaches that are beyond the control of individual governments and will necessitate international action. Therefore, the recommendations contained in this report are made with the understanding that health security is a collective responsibility, and a robust international health security architecture is required to support countries at increased risk. As a result, in addition to the many recommendations intended for national leaders, the GHS Index also includes recommendations aimed at decision makers within the UN system, international organizations, donor governments, philanthropies, and the private sector. These are especially important in the case of fast-spreading, deliberately caused, or otherwise unusual outbreaks that could rapidly overwhelm the capability of national governments and international responders.

Overall Finding

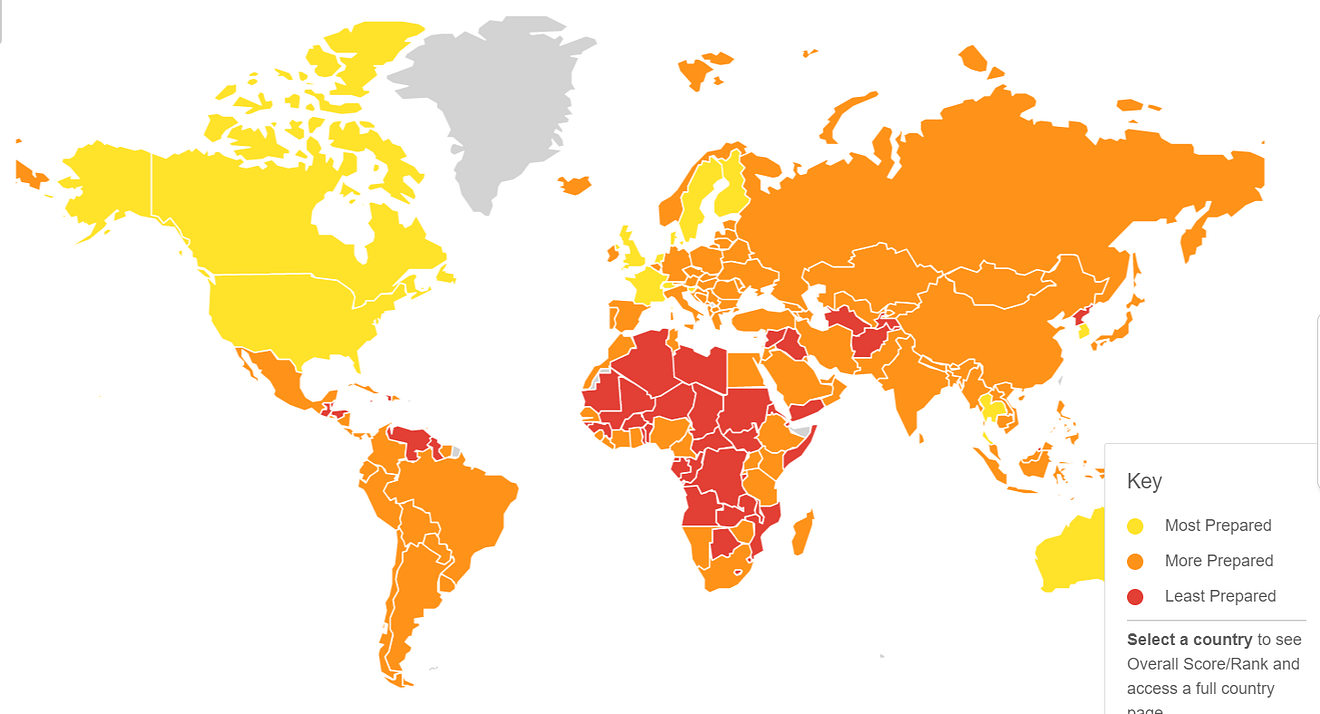

National health security is fundamentally weak around the world. No country is fully prepared for epidemics or pandemics, and every country has important gaps to address.

The GHS Index analysis finds no country is fully prepared for epidemics or pandemics. Collectively, international preparedness is weak. Many countries do not show evidence of the health security capacities and capabilities that are needed to prevent, detect, and respond to significant infectious disease outbreaks. The average overall GHS Index score among all 195 countries assessed is 40.2 of a possible score of 100. Among the 60 high-income countries, the average GHS Index score is 51.9. In addition, 116 high- and middle-income countries do not score above 50.

Overall, the GHS Index finds severe weaknesses in country abilities to prevent, detect, and respond to health emergencies; severe gaps in health systems; vulnerabilities to political, socioeconomic, and environmental risks that can confound outbreak preparedness and response; and a lack of adherence to international norms.

GHS Index Category Scores:

- Prevention: Fewer than 7% of countries score in the highest tier for the ability to prevent the emergence or release of pathogens.

- Detection and Reporting: Only 19% of countries receive top marks for detection and reporting.

- Rapid Response: Fewer than 5% of countries scored in the highest tier for their ability to rapidly respond to and mitigate the spread of an epidemic.

- Health System: The average score for health system indicators is 26.4 of 100.

- Compliance with International Norms: Less than half of countries have submitted Confidence-Building Measures under the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) in the past three years, an indication of their ability to adhere to important international norms and commitments related to biological threats.

- Risk Environment: Only 23% of countries score in the top tier for indicators related to their political system and government effectiveness.

Recommendations

The report offers 33 individual recommendations related to the data findings across its 6 categories. The following is a subset of high-level recommendations related to overarching findings. Download the report for the full listing of recommendations.

- National governments should commit to take action to address health security risks. Leaders should closely coordinate and track in-country health security investments with an emphasis on coordinating them with improvements to routine public health and healthcare systems.

- Health security capacity in every country should be transparent and regularly measured. The results of those external evaluations and self-assessments should be published at least once every two years.

- National and international health, security, and humanitarian leaders should improve coordination among sectors, including operational links between security and public health authorities, in response to high-consequence biological events, deliberate attacks, and events occurring in insecure environments. They also should work to reduce political and socioeconomic risk factors that can impede outbreak response, including in conflict zones.

- New financing mechanisms to fill epidemic and pandemic preparedness gaps are urgently needed and should be established. These could include a new multilateral global health security financing mechanism, such as a global health security matching fund; expansion of availability of the World Bank International Development Association (IDA) allocations to allow for preparedness financing; and/or development of other new ways-including through existing donor and multilateral financing programs for global health and disaster preparedness and response-to expand resources to incentivize countries to prioritize preparedness funding.

- The Office of the UN Secretary-General, working in concert with the WHO, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, and the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs, should designate a permanent facilitator or unit for high-consequence biological events that could overwhelm the capacities of the current international epidemic response architecture and result in mass casualties. This function would not be operational in nature, but rather the facilitator or unit would convene the public health, security, and humanitarian sectors before and during crises to identify and fill gaps in global preparedness specific to rapidly spreading events with the potential for great loss of life. The person or unit with this responsibility also would spur simulation exercises in concert with the UN Operations and Crisis Centre to promote unity of effort across public health, humanitarian, and security-led responses.

- Countries should test their health security capacities and publish after-action reviews, at least annually. By holding annual simulation exercises, countries will show commitment to a functioning system. By publishing after-action reviews, countries can transparently demonstrate that their response capabilities will function in a crisis and can identify areas for improvement.

- National governments and donors should take into account countries’ risk factors for significant disease outbreaks when making resources available to support health security capacity development. Countries with low scores related to risk environment should be identified as priority areas for capacity development and should receive prompt international assistance when infectious disease emergencies occur within their borders.

- Given the enormous national need, the UN Secretary-General should call a heads-of-state-level summit on biological threats by 2021 focused on creating sustainable health security financing and new international emergency response capabilities.

Originally published at https://www.ghsindex.org.