The Health Foundation

Tom Hardie, Tim Horton, Matt Willis, Will Warburton

June, 2021

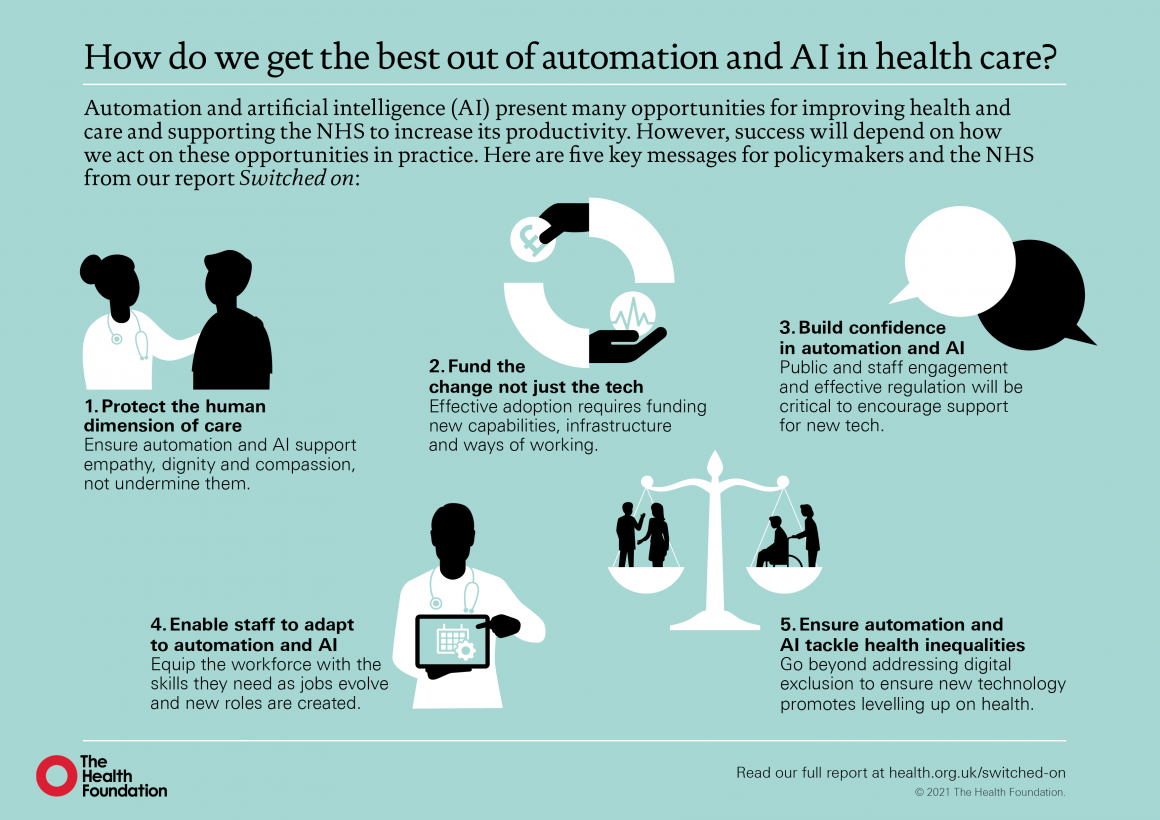

Key messages

- As the NHS emerges from the latest wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are hopes that technologies such as automation and artificial intelligence (AI) will be able to help it recover, as well as meet the very significant future demand challenges it was already facing (and which have since grown worse).

- Drawing on learning from the Health Foundation’s research and programmes, along with YouGov surveys of over 4,000 UK adults and 1,000 NHS staff, this report explores the opportunities for automation and AI in health care and the challenges of deploying them in practice.

- We find that while these technologies hold huge potential for improving care and supporting the NHS to increase its productivity, in developing and deploying them we must be careful not to squeeze out the human dimension of health care, and must support the health and care workforce to adapt to and shape technological change.

- The nature of health care constrains the use of automation and AI technologies in important ways.

- Health care is a service that is fundamentally co-produced between patients and clinicians, making the human, relational dimension critically important to the quality of care.

- The prospect of health care becoming more impersonal with less human contact was ranked the biggest risk of automation in both our public and NHS staff surveys.

- Much of what is known about the use of automation is taken from product manufacturing, meaning caution is required in assessing how well ideas and strategies from the wider literature might translate into health care.

- Given the nature of work in health care is different to many other industries, the impact of these technologies on work will also tend to be different.

- In many cases, automation and AI technologies will be deployed to support rather than replace workers, potentially improving the quality of work rather than threatening it.

- Particular opportunities exist for the automation of administrative tasks, freeing up NHS staff to focus on activities where humans add most value — which is especially important at a time when the NHS is struggling with significant demand pressures and longstanding workforce shortages.

- In other cases, automation and AI can significantly enhance human abilities, such as with information analysis to support decision making, with the dividends accruing through combining human and machine input.

- Government and NHS leaders have an important role to play in working with and supporting health care workers to respond to the rise of automation and AI, especially those parts of the workforce that may be more heavily impacted.

- The NHS staff we surveyed were on balance slightly optimistic about the future impact of automation, with more thinking the main impact would be to improve the quality of work rather than to threaten jobs and professional status.

- Nevertheless, there were occupational differences in these views, highlighting that these technologies may have an uneven impact across the workforce.

- The benefits of a new technology clearly don’t come from how it performs in isolation, but from fitting it successfully into a live health care setting and redesigning roles and ways of working to derive the benefits of the new functionalities it offers.

- And the journey from having a viable technology product to successful use in practice is often significant.

- Teams and organisations will need to consider the ‘human infrastructure’ and processes that need to accompany the technology, and policymakers, organisational leaders and system leaders will need to fund ‘the change’ not just ‘the tech’.

- Government, working with health care professions and industry, needs to engage proactively with the automation agenda to shape outcomes for the benefit of patients, health care workers and society as a whole.

- In particular, government and NHS leaders have an important role to play in identifying and articulating NHS needs and priorities, working proactively with researchers and industry to ensure that technologies are developed to meet important health care problems, and supporting the development and adoption of technologies in practice.

- While new, cutting-edge medical applications of automation and AI often steal the headlines, there are also important quality and efficiency gains to be made through applying these technologies to more routine, everyday tasks such as dealing with letters or appointment scheduling.

- There is also scope to get more out of existing applications of these technologies. So it is important for the NHS to have strategies in place for doing this, as well as supporting the development of new technologies.

- Our surveys found public and NHS staff opinion divided on whether automation and AI in health care are a good thing or a bad thing.

- Majorities said the benefits and risks were finely balanced, and some groups tended to be less positive than others.

- So government and NHS leaders must engage with the public and NHS workforce to raise awareness and build confidence about technology-enabled care as well as to better understand views about how these technologies should and should not be applied in health care, how we can ensure they serve the needs of all groups, and how important risks should be mitigated.

- Notably, our surveys also found that those who had already heard about these technologies tended to be more positive about them, so helping to familiarise people with this topic could play an important role in shaping attitudes.

Contents

Key points

Introduction

1. A brief introduction to automation and AI

1.1. What are automation and AI?

1.2. Policy approaches to support automation and AI in health care

1.3. Public, patient and professional attitudes to automation and AI

2. The potential for automation and AI in health care

2.1. Types of task amenable to automation

2.2. Application to administrative tasks in health care

2.3. Application in clinical services

3. Challenges for applying automation and AI in health care

3.1. The human dimension

3.2. The complexity of work in health care

3.3. Challenges for implementing automation and AI in health care

4. Implications for automation and AI in health care

4.1. How automation will affect work in health care

4.2. Perceptions of the benefits and risks of automation and AI in health care

4.3. Considerations for policymakers, organisation and system leaders, and

practitioners

4.4. Conclusion

References

Introduction

This report presents the findings of Health Foundation research on the opportunities and challenges for automation and artificial intelligence (AI) in health care, alongside some of the findings of a recent research study by the University of Oxford (henceforth ‘the Oxford study’), supported by the Health Foundation, into the potential of automation in primary care in England (described further in Box 2).

We explore the increasing number of areas in which automation, AI and robotic technologies are being applied to both clinical and administrative tasks, the challenges for making automation work on the front line, what automation might mean for the future of work in health care, and how the NHS can get this agenda right for the long term.

As well as the Oxford study, the report draws on a wide range of other academic studies in this field, plus learning from across the Health Foundation’s programmes, fellowships, research and evaluations. This research is also supplemented by surveys of the UK public and NHS staff, to explore views about automation and AI in health care.

By sharing learning from our programmes on how to make change happen, our aim is to increase understanding among policymakers, organisation and system leaders and front-line staff of what it takes to turn promising ideas into improvements in health and care. That requires bridging the gap between policy and practice.

It also requires exploring the human side of health care as well as the technical, to understand what its social and relational dimensions mean for how we should go about improving services.

Nowhere are these concerns more relevant than with health technology and automation, where too often the temptation is to focus on the technology itself rather than on how people use it or experience it.

And where too often the temptation is to see the algorithm, the software or the new piece of kit as the answer, rather than as an enabler of change — one that will only help if responding to an accurate diagnosis of what is needed.

It is these kinds of issues and concerns that we seek to explore in this report.

Box 1: Defining automation

____________________________________________________________________

Automation, at its simplest, is the use of technology to undertake tasks with minimal human input. In this report, we use the term broadly to include:

- the full automation of tasks and also the partial automation of tasks (where only certain components of a task are automated)

- technologies that operate autonomously or semi-autonomously, and also technologies that automate tasks without operating autonomously

- the use of technologies to support humans in performing tasks (for example, the automation of information analysis to assist human decision making), as well as the use of technologies to replace humans in performing tasks (for example, the automation of all stages of a decision process)

- applications of technologies such as AI and robotics that are creating new opportunities for automation.

____________________________________________________________________

The current context

Recent advances in computing and data analytics, coupled with the increasing availability of large datasets, are pushing the boundaries of what is possible with automation, giving rise to a host of new opportunities, from driverless vehicles to robotic carers.

Many believe automation will transform the labour market — not just in sectors like manufacturing, transport and financial services, but also in health care — leading to significant changes in the nature of work and the skills needed to succeed in the future job market. In health care, these technologies also hold great potential to improve the quality of care for patients and the quality of work for staff, something that has been recognised by policymakers across the UK — in England, for example, through the NHS Long Term Plan, the Department of Health and Social Care’s Technology Vision, the creation of NHSX and the investment of £250m to create the NHS AI Lab.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also given fresh impetus to the use of technologies in health care, including technologies that could be classed as automation such as devices for monitoring health.

And where they have been successful, there is hope in many quarters that the NHS will be able to build on this progress and embed these technologies as part of ‘business as usual’.

There is also hope that automation, AI and robotic technologies will be one important part of the answer to coping with the unprecedented demand pressures the NHS is facing as it moves beyond the emergency phase of the pandemic, including a huge backlog of elective care — pressures that will necessitate increased productivity as well as expanded capacity.

In this sense, COVID-19 has only heightened the need for the NHS to have effective strategies for these technologies and a detailed understanding of how to support their design, implementation and use.

However, while there is rightly much excitement about the potential of automation, AI and robotics, what we also see from the Health Foundation’s programmes is that deciding where these technologies should (and should not) be applied, and understanding how they can be implemented and used successfully, are challenging issues that will require careful consideration by policymakers, organisation and system leaders, and those leading change on the front line.

And while it is the promise of new technologies that receives much of the policy and media focus, we believe the challenges and constraints require just as much attention.

It is precisely an awareness of these challenges and constraints that will be needed in developing effective automation strategies for the future.

As the Health Foundation’s report Shaping Health Futures highlights, policymakers and system leaders need a realistic understanding of the big trends on the horizon, like automation and AI, and need to factor them into strategic decision making.[1]

This is also important for health and care professions, and the health and care workforce as a whole, which some have argued will be transformed by the current wave of technological change. It also has significance for those in industry, who will need to work closely with NHS staff and patients in developing new technologies.

As automation and AI technologies continue to develop and their use in health care becomes more widespread, it is crucial we shape their impact for the benefit of staff, patients and society as a whole.

Content overview

Chapter 1 provides background on automation in health care. It briefly explores the concept of automation, its relationship to AI and robotics, and the impact it could have on the future of work. It also highlights some recent policy responses to automation and AI in the UK, and looks at public and professional attitudes to automation.

Chapter 2 considers the types of task most amenable to automation. It then explores some of the different ways in which automation and AI are being applied, or could be applied, in health care, to both clinical and administrative tasks.

Chapter 3 looks at the main constraints and challenges that will need to be understood and addressed in order to make the most of automation and AI in health care. These include the challenges of replicating human skills, the indispensability of human agency in certain aspects of health care and the complexity of many kinds of health care tasks. This chapter also explores some challenges of implementing and using automation and AI technologies effectively in practice.

Chapter 4 highlights the implications of these constraints and challenges for policymakers, organisation and system leaders, and those leading change on the front line. It reflects on how automation might affect work in health care, explores public and NHS staff views on the benefits and risks of automation in health care, and concludes with recommendations for policymakers, practitioners, organisation and system leaders (including leaders in providers, health boards, integrated care systems, and regional and national bodies) and industry

Box 2: The Oxford automation study — The Future of Healthcare: Computerisation, Automation and General Practice Services

____________________________________________________________________

The high volume of administrative work in health care is well documented, and a particular challenge in general practice.

This study sought to assess the potential of automation technologies currently available on the market to conduct administrative tasks in primary care.

Funded by the Health Foundation, it was led by the Oxford Internet Institute, the Oxford Department of Engineering Science and the Oxford Martin School during 2017–19.

Through over 350 hours of ethnographic observation at six primary care centres in England, the researchers identified 16 unique occupations performing over 130 different tasks.

Using ratings of task automatability from a survey of automation experts and combining this with data from the O*NET database (a repository of US occupational definitions that describes the skills, knowledge and abilities different kinds of task require), the team then applied a machine learning model to assess the automatability of each task – ranging from ‘not automatable today’ to ‘completely automatable today’.

The results were then analysed to produce insights about the nature of work in primary care, and about where automation is most likely and where it could be most useful.

The findings of the research, published in BMJ Open and by the University of Oxford, show that:

- 44% of all administrative work performed in general practice can be either mostly or completely automated, such as running payroll, sorting post, transcription work and printing letters

- automating administrative tasks has the potential to free up staff to spend more time with patients, improving the quality of care and the quality of work

- while every occupation in general practice, including clinical roles, involves a significant amount of time performing administrative work, no single full-time occupation could be entirely automated.

____________________________________________________________________

About the authors:

Tom Hardie, Tim Horton, Matt Willis, Will Warburton

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank a number of people who have provided helpful comments and insights during the production of this report. These include Amanda Begley, Ben Bray, Alan Davies, Jennifer Dixon, Mary Dixon Woods, Ruth Glassborow, Trish Greenhalgh, Nik Haliasos, Hugh Harvey, Kassandra Karpathakis, Josh Keith, Xiaoxuan Liu, Michael MacDonnell, Erik Mayer, Breid O’Brien, Sarah Jane Reed, Paul Sullivan, Richard Turnbull and Wenjuan Wang.

Originally published at

PDF Version