Our centers for healing have turned into breeding grounds for dangerous — even deadly — infections.

Consumer Reports’ new Ratings of more than 3,000 U.S. hospitals show which do a good job of avoiding the infections — and which don’t.

DISCLAIMER: This is a republication of the original article by “Consumer Reports”. The Editor of this blog has not necessarily endorse the analysis and the recommendations. The purpose of the republication is to raise awareness about the issue.

Consumer Reports

July 29, 2015

everydayhealth

Hospital Acquired Infections Are a Serious Risk — Consumer Reports

Fighting Bad Bacteria With Good Ones

In the ongoing war of humans vs. disease-causing bacteria, the bugs are gaining the upper hand. Deadly and unrelenting, they’re becoming more and more difficult to kill.

You might think of hospitals as sterile safety zones in that battle. But in truth, they are ground zero for the invasion.

Though infections are just one measure of a hospital’s safety record, they’re an important one. ]

Every year an estimated 648,000 people in the U.S. develop infections during a hospital stay, and about 75,000 die, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). That’s more than twice the number of people who die each year in car crashes.

And many of those illnesses and deaths can be traced back to the use of antibiotics, the very drugs that are supposed to fight the infections.

648,000 people in the U.S. develop infections during a hospital stay per year , and about 75,000 die …

And many of those illnesses and deaths can be traced back to the use of antibiotics, the very drugs that are supposed to fight the infections.

Terry Otey appears to be one casualty in that ongoing battle. Three years ago, a few weeks after an overnight stay for back surgery at Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett, Wash., he went to the emergency room vomiting, dizzy, and with excruciating back pain. Bacteria known as MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus) had taken hold in his surgical incision and quickly spread to his heart. He died in the hospital about three months later, following a cascade of serious health problems. “He just wanted to ease his back pain enough to play golf,” says his sister, Deborah Bussell.

Kellie Pearson, 49, a farmer in northern California, says she encountered a different kind of bug after having heart surgery last April. Her doctors prescribed an antibiotic in the hopes that it would prevent a postsurgical infection. Instead the drug killed off healthy bacteria in her body, and another germ, C. diff (clostridium difficile), swooped in, causing diarrhea so severe that she had to stay in the hospital an additional five days until doctors could rein in the potentially deadly infection.

She recovered but soon realized that she wasn’t the only patient suffering. “When I was able to walk down the hall in the hospital,” she says, “I was horrified to see room after room with C. diff caution signs on their doors warning that the patients inside, like me, had been infected.”

In the Danger Zone

“Hospitals can be hot spots for infections and can sometimes amplify spread,” says Tom Frieden, M.D., director of the CDC. “Patients with serious infections are near sick and vulnerable patients — all cared for by the same health care workers sometimes using shared equipment.”

Making the situation even more dangerous is the widespread, inappropriate use of antibiotics that’s common in hospitals, which encourages the growth of “superbugs” that are immune to the drugs and kills off patients’ protective bacteria.

It’s “the perfect storm” for infections to develop and spread, says Arjun Srinivasan, M.D., who oversees the CDC’s efforts to prevent hospital-acquired infections.

“We’ve reached the point where patients are dying of infections in hospitals that we have no antibiotics to treat.”

Making the situation even more dangerous is the widespread, inappropriate use of antibiotics that’s common in hospitals, which encourages the growth of “superbugs” that are immune to the drugs and kills off patients’ protective bacteria.

But there’s hopeful news: Some hospitals are taking steps to reduce infections and end inappropriate antibiotic use. “But others have made little effort,” Srinivasan says.

But there’s hopeful news: Some hospitals are taking steps to reduce infections and end inappropriate antibiotic use. “But others have made little effort,”…

Red Flags for Bad Bacteria

We are focusing on C. diff and MRSA for two important reasons.

First, the infections are common and deadly. More than 8,000 patients each year are killed by MRSA; almost 60,000 are sickened by the infections.

The bacteria often find their way into patients’ bodies through the lines and tubes that doctors use to deliver medication and nutrition to patients, or via surgical incisions, as happened to Terry Otey.

C. diff is an even bigger concern. Kellie Pearson is one of the 290,000 Americans sickened by the bacteria in a hospital or other health care facility each year. She was lucky: At least 27,000 people in the U.S. die with those infections annually.

Second, poor MRSA or C. diff rates can be a red flag that a hospital isn’t following best practices in preventing infections and prescribing antibiotics.

That could not only allow C. diff and MRSA to spread but also turn the hospital into a breeding ground for other resistant infections that are even more difficult to treat.

We are focusing on C. diff and MRSA for two important reasons.: (1) The infections are common and deadly. More than 8,000 patients each year are killed by MRSA; almost 60,000 are sickened by the infections.,

(2) poor MRSA or C. diff rates can be a red flag that a hospital isn’t following best practices in preventing infections and prescribing antibiotics.

For example, as dangerous as MRSA is, an infection can be cured if it is treated promptly with vancomycin, long held out as an “antibiotic of last resort.” But, in part because that drug is now so often used in hospitals, another resistant strain of bacteria — vancomycin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, or VRSA — is emerging. “VRSA infections pose special challenges; they can be even more difficult to treat than MRSA,” Srinivasan says.

Bacteria often find their way into patients’ bodies through the lines and tubes that doctors use to deliver drugs and nutrition.

Hospitals That Rate Well

To earn our very top rating in preventing MRSA or C. diff, a hospital has to report zero infections — an admittedly high bar.

Still, 322 hospitals across the country were able to achieve that level in our MRSA ratings, and 357 accomplished it for C. diff, showing that it is possible. (Experts say some hospitals might game the system.

Read more about how hospitals fudge the numbers, and help us identify those that may not accurately report infections.)

More hospitals were able to earn either of our two highest ratings — indicating that they reported either zero infections or did much better than predicted compared with similar hospitals: 623 hospitals received high marks for MRSA, and 917 did so for C. diff.

Hospitals really begin to distinguish themselves when they earn high ratings against both infections: 105 hospitals succeeded in that. Even better, some hospitals excel against not only MRSA and C. diff but also other infections that the CDC tracks and that are in our Ratings. Those include surgical-site infections and infections linked to urinary catheters or central-line catheters, large tubes that provide medication and nutrition.

“Hospitals that do well against infections across the board have figured ] something out and deserve special mention,” Peter says. Only 9 hospitals in the country — those featured in the “Highest-Rated in Infection Prevention” chart — earned that high honor.

And Hospitals That Don’t

You won’t find any familiar, big-name hospitals on that top-performing list.

In fact, several high-profile hospitals got lower ratings against MRSA, C. diff, …

… including the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, and Ronald Reagan University of California Los Angeles Medical Center.

Those are all large teaching hospitals in urban areas, which in our analysis did not do as well as nonteaching hospitals of similar sizes in similar settings.

That could be because teaching hospitals may do a better job of reporting infections. Or, as a representative for Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center told us, they may see sicker patients or have more patients undergoing complex procedures.

Those are all large teaching hospitals in urban areas, which in our analysis did not do as well as nonteaching hospitals of similar sizes in similar settings.

…only 6 percent of teaching hospitals received one of our two top scores against C. diff, compared with 14 percent of similar nonteaching hospitals.

Although the CDC adjusts the data to account for some of those factors, teaching hospitals tend to perform worse.

For example, only 6 percent of teaching hospitals received one of our two top scores against C. diff, compared with 14 percent of similar nonteaching hospitals.

“Yes, teaching hospitals face special challenges. But they are also supposed to be places where we identify best practices and put them to work,” says Lisa McGiffert, director of the Consumer Reports Safe Patient Project. “Obviously, that is not happening as well as it should.”

Larger hospitals also tended to do worse in our Ratings.

That could be because patients in smaller hospitals are less likely to be exposed to infections. But some larger hospitals managed to do a good job avoiding infections.

Case in point: Harlem Hospital Center in New York City earned high ratings against MRSA and C. diff.

Or consider Northwest Texas Healthcare System in Amarillo, Texas. It made it onto our list of top hospitals in the prevention of all of the infections included in our Ratings.

Larger hospitals also tended to do worse in our Ratings.

What’s behind our Ratings?

Our hospital Ratings are based on data on infections, readmissions, complications, other adverse events, and more.

What our ratings show?

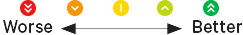

- Consumer Reports’ hospital Ratings shine a spotlight on the problem. For the first time ever, those Ratings include information on MRSA and C. diff infections, based on data that hospitals submit to the CDC. And the results are sobering.

- Three out of 10 hospitals in our Ratings got one of our two lowest scores for keeping C. diff in check; four out of 10 got low marks for avoiding MRSA. Only 6 percent of hospitals scored well against both infections.

- “Hospitals need to stop infecting their patients,” says Doris Peter, Ph.D., director of the Consumer Reports Health Ratings Center. “Until they do, patients need to be on high alert whenever they enter a hospital, even as visitors.”

- But there’s plenty that hospitals can do to stop the spread of deadly, sometimes resistant infections, and there are steps you can take as well to keep you and your family safe.

- Highest Rated in Infection Prevention

- The 9 hospitals below earned high ratings in avoiding MRSA and C. diff, as well as three other infections (see Guide to the Rating, below). The bigger a hospital is the more difficult it is for it to do well, so hospitals are listed here in order of patient volume. See our complete hospital Ratings. (Note that the charts shown here differ from those in the September 2015 issue of Consumer Reports magazine because of new data released by the government after that issue went to press.)

See the original publication for the full list

The 12 hospitals below earned low ratings in avoiding MRSA and C. diff, as well as three other infections (see the Guide to the Ratings). They’re listed alphabetically. (Note that the charts shown here differ from those in the September 2015 issue of Consumer Reports magazine because of new data released by the government after that issue went to press.)

Guide to the Ratings.

These Ratings reflect how hospitals performed in a snapshot in time, based on data hospitals reported to the CDC between October 2013 and September 2014. The data are released periodically throughout the year. (The Ratings that appear in the September 2015 print issue of Consumer Reports magazine were the most currently available at publication, based on data reported to the CDC between July 2013 and June 2014.) Infections Composite indicates how a hospital did against MRSA and C. diff infections plus surgical-site infections and infections associated with urinary-tract and central-line catheters. The CDC adjusts to account for factors such as the health of a hospital’s patients, its size, and whether it’s a teaching hospital. See our complete and the most current hospital Ratings as well as more about how we rate hospitals.

What Safe Hospitals Do

Good hospitals focus on the basics:

USE ANTIBIOTICS WISELY. Almost half of hospital patients are prescribed at least one antibiotic, Srinivasan says, but “up to half the time the drug is inappropriate.” To combat antibiotic misuse, many good hospitals have “antibiotic stewardship” programs, often headed by a pharmacist trained in infectious disease, to make sure that patients get the right drug, at the right time, in the right dose.

Such programs often monitor the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Doctors at some hospitals use three times more of those all-purpose bug killers than others. Reducing broad-spectrum prescriptions by 30 percent would “cut hospital rates of C. diff by more than 25 percent, plus reduce antibiotic resistance,” says Clifford McDonald, M.D., a CDC epidemiologist

KEEP IT CLEAN. C. diff and MRSA can live on surfaces for days and can be passed from person to person on hospital equipment or the hands of health care workers. To prevent that, hospitals must be kept scrupulously clean. “Infection control is all about the basics, starting with hand hygiene,” says Christine Candio, president and CEO of highly rated St. Luke’s Hospital in Chesterfield, Mo. She reminds patients, “it’s your right to ask” staff to wash up. In fact, fastidious hand washing slashes rates of C. diff, MRSA, and other infections. St. Luke’s also “prioritizes cleanliness,” in some cases exceeding infection-control guidelines — cleaning the rooms of C. diff patients twice daily, for example, and replacing curtains between patients.

What More Needs to Be Done

Steps such as those, plus federal mandates for some public reporting of infections data, have already led to reduced rates of certain infections. Still, McGiffert says hospitals need to do more:

- Consistently follow the established protocols for managing superbug infections, such as using protections including gowns, masks, and gloves by all staff.

- Be held financially accountable. Already, hospitals in the bottom 25 percent of the government’s data at preventing certain complications now have Medicare payments docked 1 percent. But they should also have to cover all costs of treating infections patients pick up during their stay.

- Have an antibiotic stewardship program. That should include mandatory reporting of antibiotic use to the CDC.

- Accurately report how many infections patients get in the hospital. And the government should validate those reports.

- Be transparent about infection rates. For instance, Cleveland Clinic acknowledges its below-average performance in C. diff prevention on its website. “That’s refreshingly candid,” Peter says.

- Promptly report outbreaks to patients, as well as to state and federal health authorities. Those agencies should inform the public so that patients can know the risks before they check into the hospital.

Fighting Bad Bacteria With Good Ones

Antibiotics kill off not only bad bacteria that make you sick but also good bacteria that help keep you healthy.

So replenishing the good bugs in your digestive tract seems to make sense.

That’s the idea behind two growing trends: probiotics and fecal transplants.

PROBIOTICS

There’s some evidence that probiotics might shorten a bout of diarrhea caused by antibiotics. And an analysis of 23 clinical trials found that taking probiotics with antibiotics can greatly cut the risk of diarrhea caused by C. diff.

Probiotics may be worth a try if you’re on antibiotics for more than a few days, taking two antibiotics at once, or you’re switched from one drug to another. People older than 65 and those who take an acid-blocking drug such as Nexium or Prilosec are at higher risk for C. diff; check with your doctor to see whether probiotics will help you.

Research suggests that the most effective probiotics are combinations of L. acidophilus, L. casei, L. rhamnosus, and S. boulardii. To reduce the risk of diarrhea caused by C. diff, the most effective dose is thought to be more than 10 billion colony forming units, or CFU, daily.

You don’t have to take a pill to get those good bacteria. Yogurts we tested several years ago contained an average of 90 billion to 500 billion CFU per serving. Probiotic supplements contained less, from just fewer than 1 billion to 20 billion CFU per capsule. Read more about probiotics and yogurt.)

Probiotics should be avoided by people with compromised immune systems or serious medical conditions because of a rare risk of bloodstream infections

FECAL TRANSPLANTS

For C. diff infections that keep coming back, a “fecal microbiota transplant” is nothing short of a miracle. In the procedure, a doctor places stool from a healthy donor into an infected person’s colon, usually using colonoscopy. The idea is to repopulate the colon with good bacteria to fight off C. diff. Research shows that it works about 90 percent of the time. In 2013 the Food and Drug Administration decided to allow doctors to perform the procedure in C. diff patients with diarrhea and other symptoms even after being treated with antibiotics.

Some recent reports suggesting that fecal transplants may have other benefits — including weight loss. As a result, a cottage industry of “poo practitioners” has emerged. Some people are even going the DIY route.

“That’s a terrible idea,” says Christina Surawicz, M.D., a gastroenterologist and professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine. For example, there have been reports of people developing autoimmune disorders after the procedure and even suddenly gaining weight.

Instead, if you have C. diff, look for an infectious disease doctor or gastroenterologist with experience in the procedure. The stool can come from a friend or family member, or doctors can buy frozen specimens from screened donors. Check with your insurance company to see whether it will cover fecal transplants to treat C. diff.

Yogurts we tested several years ago contained an average of 90 billion to 500 billion CFU per serving.

Germ Warfare: Protect Yourself Against Superbugs

First step: Check our Ratings to see how hospitals in your community compare in preventing infections and other measures of hospital safety. But bad things can happen even in good hospitals.

For example, Terry Otey developed his infection after a 2012 surgery in a hospital that now gets one of our higher ratings against MRSA. Our experts say there are several things you can do when you’re in the hospital and after you’re discharged to minimize your risk and spot symptoms of possible infection early.

Conclusion

AT HOME

- If you’ve been in the hospital, “assume you’ve been exposed to potentially dangerous bacteria,” says Lisa McGiffert, director of the Consumer Reports Safe Patient Project. Here’s what to do when you get home to keep yourself and your family safe:

- WATCH FOR WARNING SIGNS. Those include fever, diarrhea, worsening pain, or an incision site that becomes warm, red, and swollen. People at particular risk include adults 65 and older as well as infants, anyone on antibiotics, and people with a compromised immune system.

- PRACTICE GOOD HYGIENE. If you or someone you live with is diagnosed with a hospital-acquired infection after being discharged from the hospital, take extra precautions to make sure that it doesn’t spread:

- Clean frequently touched surfaces with 1 part bleach mixed with 10 parts water. Reserve a bathroom for the infected person. If that’s not possible, use the bleach solution to disinfect surfaces between uses.

- Don’t share toiletries or towels; use paper towels rather than cloth hand towels.

IN THE HOSPITAL

- CONSIDER MRSA TESTING. A nasal swab can detect low levels of MRSA and allow medical staff to take precautions, such as having you wash with a special soap before you are admitted.

- INSIST ON CLEANLINESS. Ask to have your room cleaned if it looks dirty.

- Bring bleach wipes for bed rails, doorknobs, and the TV remote.

- Bring bleach wipes for bed rails, doorknobs, and the TV remote. Insist that everyone who enters your room wash his or her hands. Keep your own hands clean, washing regularly with soap and water.

QUESTION ANTIBIOTICS. Make sure that any anti-biotics prescribed to you in the hospital are needed and appropriate for your infection.

WATCH OUT FOR HEARTBURN DRUGS. Medications such as Nexium or Prilosec increase the risk of C. diff by reducing stomach acid that normally helps keep the bug in check. So ask whether the drug is needed and, if so, request the lowest dose for the shortest possible time.

ASK EVERY DAY WHETHER CATHETERS, VENTILATORS, OR OTHER TUBES CAN BE REMOVED. The risk of infection increases the longer they are left in place.

SAY NO TO RAZORS. If you need to be shaved, use an electric hair remover, not a razor, because any nick can provide an opening for infection.

How to Say No to Antibiotics

On any given day in the hospital, half of patients are given an antibiotic and 25 percent get two or more, according to the CDC. But up to half of the time, doctors don’t use the drugs right. “It can feel awkward to talk to your doctor about antibiotics,” says Conan MacDougall, Pharm.D., a team leader for antibiotic stewardship at the University of California at San Francisco. But asking a few simple questions can “encourage physicians to be more thoughtful about prescribing,” MacDougall says.

What is this drug for?

If your doctor suspects a bacterial infection, ask whether you can be tested for it; results can confirm the infection and determine the type of bug, which can dictate the type of antibiotic that works best.

What type is it?

If a narrower-spectrum drug such as penicillin will work against your infection, that’s usually a better choice than a broad-spectrum drug.

How long should I take it?

Ask your doctor to prescribe the drug for the shortest time possible. (Be sure to take it for that duration.) Ask for the type and dose to be re-evaluated when test results are in. A common error, MacDougall says, is not switching from a broad-spectrum drug to a targeted one once the bug is identified.

What about side effects?

Most antibiotics are well tolerated; but in addition to C. diff, antibiotics can trigger serious allergic reactions, including rashes, swelling of the face and throat, and breathing problems. Some antibiotics have been linked to torn tendons and permanent nerve damage.

ILLUSTRATION BY JUDE BUFFUM

Originally published at https://www.consumerreports.org.

Names mentioned

Tom Frieden, M.D., director of the CDC

Arjun Srinivasan, M.D., who oversees the CDC’s efforts to prevent hospital-acquired infections.

Lisa McGiffert, director of the Consumer Reports Safe Patient Project

RELATED ARTICLES