the health strategist . institute

research and strategy institute — for continuous transformation

in value based health, care, and tech

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Chief Researcher & Editor of the Site

March 31, 2023

This executive summary outlines the views of Allen Kachalia, Senior Vice President of Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine; Director, Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality regarding the state of safety in healthcare.

For the full publication of the original paper “Lessons from Health Care Leaders: Rethinking and Reinvesting in Patient Safety”, please refer to the 2nd part of the post.

ONE PAGE SUMMARY

Allen Kachalia, MD, JD [Johns Hopkins / Armstrong Institute]

The study conducted by Bates and colleagues on hospital safety highlights the persistent challenge of delivering high-quality and safe care to all patients.

While there may be disagreements about the actual rate of preventable harm, most agree that there are quality and safety gaps that still need to be addressed.

These gaps have become even more challenging to close post-pandemic, with greater staff turnover and vacancies raising the risk of error and preventable harm.

However, there is cause for optimism, as we have seen increasing investment and attention toward quality improvement over the last two decades.

Health care organizations need to prioritize patient outcomes, understand social determinants of health, and use information technology, including AI, to measure what matters.

The pandemic has brought into sharp relief that health care is not delivered in a vacuum, and organizations must keep looking at everything they do by first asking what each step means for the quality of the health care they deliver.

It is time to redouble efforts and use all the insights accumulated over the past 25 years to make care truly safe for all.

It is time to redouble efforts and use all the insights accumulated over the past 25 years to make care truly safe for all.

OVERVIEW [Thomas Lee]

Health care quality and safety leaders from a wide range of organizations globally react to seminal articles in the New England Journal of Medicine on the continuing prevalence of preventable harm.

It’s still early in the year, but there’s a good chance that many of us will remember 2023 for the article by David Bates, et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine showing that adverse events remain common during hospital admissions,1 and the accompanying editorial from Don Berwick urging that leaders push safety “back to strategic prominence.”2

At NEJM Catalyst, we wanted to take the temperature of a range of health care quality and safety leaders to seek how they were thinking about these data and what was happening at their institutions.

We reached out to 13 leaders working in different roles — health care delivery, government, consulting — and different countries, all with deep experience and a passion for improving safety.

We did something similar with a group of CEOs in the early days of Covid-19.3 Then, as now, we found their reactions interesting, sobering, and yet somehow inspiring.

First, I’ll point out that every one of them said yes, and provided their reactions in just a couple of weeks.

Second, none of them pushed back on the basic conclusions of the Bates paper, which is that 2 decades of work on patient safety have not produced the improvement we need.

Many agreed with the simple statement from Eyal Zimlichman, a health care leader from Israel, who noted, “It is time to rethink our approach.”

As Jon Perlin, the CEO of The Joint Commission, wrote, “we have to acknowledge that today’s health care is brutally complex, and simple solutions are not apt to remedy varying challenges.”

But my favorite single sentence in all these comments may be that of Allen Kachalia, who leads quality and safety at Johns Hopkins: “nevertheless, there is cause for optimism.”

The work ahead may seem daunting, but the leaders commenting here seem undaunted. I’ll be doing a podcast interview with David Bates soon to get his reaction to their reactions.

— Dr. Thomas H. Lee, MD, MSc, Editor-in-Chief and Editorial Board Co-Chair, NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery

DEEP DIVE

Lessons from Health Care Leaders: Rethinking and Reinvesting in Patient Safety

Commentary from quality and safety leaders on the persistence of adverse events in care delivery — and where health care organizations should go from here.

NEJM Catalyst

April 4, 2023

Kedar S. Mate, MD

President & CEO, Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Assistant Professor of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College

I share David Bates’ serious concerns about the current state of safety today and agree with Don Berwick’s editorial comments that we need to reprioritize safety immediately.

Sadly, the serious issues with safety and persistent prevalence of adverse events in health care are not unexpected.

We have for years treated patient safety as a complex technical problem alone, while neglecting to make deeper adaptive system changes that might have more fundamentally changed the dynamics around patient safety.

This is because we have largely been in reactive and retrospective review mode.

Looking back at adverse events and understanding them is necessary, yes, but very far from sufficient.

This approach to safety improvement is akin to believing that the only key to a successful marriage is studying divorces.

We need to move quickly toward a much more proactive and prospective approach to improving safety — what some call Safety II.

While this future-looking approach can take many forms, we already have evidence of what is badly needed and may allow us to move toward solving the embedded system challenges.

Below are some of the features of a more proactive approach to ensuring safety in health care:

1.Enabled, real-time situational awareness: Tiered, daily huddles from the frontline care teams to the executive leadership suite are a proven method for increasing awareness enterprise-wide of safety risks and communicating those risks to all who need to know. They also contribute to a culture of transparency and effective communication. Real-time clinical and operational data allow clinicians and leaders to understand which patients are at risk of experiencing an adverse event before it happens.

2.Patients and family as embedded coproducers of safety and health: Patient and family members remain an underutilized and essential resource for improving every aspect of care, safety very much included. We need to center patients and their families as the primary and most crucial detectors of risk and potential deterioration. Rather than see patients and families as key contributors, our systems have tended to distrust and disregard patient and family insights. This must change. Effective engagement of patients and families will enable round-the-clock continuous monitoring of safety risks.

3.Real-time, proactive data to sense and mitigate risk: Technology has still not realized its full promise and potential to improve safety. It’s time to leverage the advances in technology that have transformed our world to generate and clearly communicate real-time data to detect and mitigate the risks inherent in caring for the sick. Novel AI-driven algorithms are increasingly useful to help identify potential adverse drug events, flag risk for falls and pressure injuries, and improve population management. A critical step in the next few years will be to ensure that the new knowledge generated by those algorithms can be matched by delivery system improvements to help clinicians act on those insights to protect the health of our patients.

3.Large-scale learning networks: Just as technology can help generate knowledge and data at the individual level, it can also help enable knowledge and insights at a whole population. Large-scale learning networks, like Solutions for Patient Safety amongst 145-plus pediatric hospitals, are the key to this kind of collective knowledge production. These networks typically connect clinicians, researchers, patients, and families in a single network to help ensure that new safety science gets rapidly implemented. Together, these stakeholder groups understand the full scope of systems, where safety risks exist, and how best to mitigate those risks.

4.Restorative just culture and communication and resolution: When something does go wrong, how we respond in the immediate aftermath (to the patient, their family, and any clinicians involved in the event) is every bit as important as a deep dive into the specific actions that led to the event. Using the principles of just culture (i.e., a culture of true accountability without blame or shame) and appreciative inquiry (i.e., emphasizing curiosity over judgment) are proven methods to effectively learn from adverse events and the best ways to prevent them in the future. Coupling these with effective communication and resolution programs allows patients, families, and clinicians to both learn from error events when they happen and to heal.

Lastly, we need to focus more than ever on the safety and standardization of the work environment.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic started, the major increases in workforce turnover have heightened the importance of standard protocols and processes.

With the increased burdens of educating and training new staff, we need to accelerate and improve training by embedding reliability in our care environments.

The safety setbacks over the past few years were surely exacerbated by the pandemic, but we were already stagnating before Covid-19 in our commitment and effort to ensure safety for patients and the workforce.

Now is the time to redouble our efforts and use all the insights we’ve accumulated over the past 25 years to make care truly safe for all.

Allen Kachalia, MD, JD

Senior Vice President of Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine; Director, Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality

The study results from Bates and colleagues on safety in hospitals highlight an ongoing challenge in health care: How do we reliably deliver high quality and safe care for all patients?

Though there may be disagreement on whether the actual rate of preventable harm is lower or higher than reported, most in health care readily agree that there are a number of quality and safety gaps that still need to be addressed.

Closing these gaps has only gotten tougher since the study was completed.

Post-pandemic, health care is witnessing greater staff turnover and vacancies (a phenomenon that’s not limited to health care) that have only raised the risk of error and preventable harm.

The rise in health care–associated infections that followed once the pandemic broke out illustrates the challenge in maintaining safety.4,5

High levels of staff burnout compound the safety challenge by making it more difficult to initiate and sustain improvement efforts.

Health care leaders and providers want their organizations to be the best when it comes to quality and safety.

The underlying question is, how do we ensure that quality and safety receive the proper prioritization?

For example, there is no question that other large problems exist in health care, such as maintaining financial solvency, staff turnover, and worker safety.

But the point that is probably too often overlooked is that steps taken to address these important problems may generate unintended quality and safety risks.

Perhaps the most obvious example is how, across the board, budget cuts can inadvertently impede or set back quality improvement efforts.

Nevertheless, there is cause for optimism.

Over the last 2 decades, we have seen increasing investment and attention toward quality improvement.

Most health care systems now have board committees and operational structures designed to elevate the organizational importance of patient outcomes.

Health care organizations need to lean into these mechanisms to stay on task with regard to proper prioritization.

Our understanding of the barriers to achieving our quality and safety goals has also vastly improved.

The pandemic has brought into sharp relief that health care is not delivered in a vacuum.

Organizations are getting better at understanding social determinants of health, and starting to address opportunities in access, adherence, and services offered to patients.

The pandemic catalyzed the use of information technology to deliver care, and this trend will likely continue.

This includes using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-abstracted clinical data to measure what matters instead of relying on administrative data.

Organizations also now understand that even supply chain decisions need to take quality and safety considerations into account (such as redundancy in suppliers).

In other words, health care organizations must keep looking at everything they do by first asking what each step means for the quality of the health care they deliver.

In other words, health care organizations must keep looking at everything they do by first asking what each step means for the quality of the health care they deliver.

The safety setbacks over the past few years were surely exacerbated by the pandemic, but we were already stagnating before Covid-19 in our commitment and effort to ensure safety for patients and the workforce.

Now is the time to redouble our efforts and use all the insights we’ve accumulated over the past 25 years to make care truly safe for all.

Now is the time to redouble our efforts and use all the insights we’ve accumulated over the past 25 years to make care truly safe for all.

Arjun Venkatesh, MD, MBA, MHS

Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine; Chief, Emergency Services, Yale New Haven Hospital; Scientist, Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation

Since collection of the data of the original Harvard Medical Practice Study in 1984,6 patient safety has moved like clockwork on the glacial evidence-based medicine treadmill. That 1984 data was published in 1991, and it took another 8 years for evidence to generate the national recommendations of the seminal Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, To Err Is Human.7 Now, a quarter century later, the Bates study describes the current state of hospital safety. A quick glance at media headlines or social media would suggest we have made no progress, with adverse events detected in over 1 in 5 inpatient hospitalizations. But I, like the ever-optimistic Ted Lasso [from the Apple TV show], see it differently: that this study is an “opportunity to be curious, not judgmental.”

As a practicing emergency physician, quality and safety researcher, and department chair, I am witness to a wholly transformed hospital care delivery system. No medication is ordered without electronic allergy-checking or administered without bar code scanning. No central line is placed without ultrasound guidance and checklist. Bates and colleagues acknowledge this in mentioning the vast strides that have been made to reduce hospital-acquired infections and other harms. These gains are sadly absent from the headlines and tweets. Does that mean medication or procedural errors are impossible? No, but several common complications such as medication administration–based anaphylaxis or iatrogenic pneumothoraxes are exceedingly rare. And hospital-acquired harms are now often more occult and grow insidiously as unintended consequences of new technologies or the structure of our health care system.

As a frontline health care worker, the greatest risk to hospital safety and health care equity is the unprecedented capacity crisis faced in acute hospital care. Virtually every emergency department and hospital in this nation is over capacity, resulting in delayed or missed diagnoses in patients who leave the emergency department without evaluations for acute conditions, increased mortality while awaiting a hospital bed in an emergency department hallway, and even critically ill patients unable to receive access to specialized or critical care. The basic premise of almost any published patient safety conceptual model assumes the availability of basic resources for care delivery, including the minimum staff, space, and materials for acute care. Our current national crisis has put all three at risk as we face record shortages of hospital-based health care workers, inpatient bed capacity has not kept pace with population and acuity growth, and supply chains for everything ranging from medications to gauze pads remain fragile. These structural forces may seem insurmountable on the surface, but can be addressed if policy makers and health system leaders embrace safety culture and apply the strong leadership called for by Bates and colleagues. As Coach Lasso would say: “Doing the right thing is never the wrong thing.”

Carla C. Braxton, MD, MBA, FACS, FACHE, and Shawn Tittle, MD

Carla C. Braxton, MD, MBA, FACS, FACHE, Chief Medical Officer/Chief Quality Officer, Houston Methodist West and Houston Methodist Continuing Care Hospitals; Associate Professor of Clinical Surgery, Houston Methodist Academic Institute; Shawn Tittle, MD, Chief Medical Officer/Chief Quality Officer, Houston Methodist Baytown Hospital

While the findings of Bates et al. demonstrate that much work remains to be done, we challenge the concept that patient safety has become less of a priority in hospital systems. In our journey toward becoming a high-reliability organization (HRO), the safety culture is deeply embedded within our eight-hospital combined academic and community-based complex care system.8 We believe that the factors that keep our system keenly focused on safety are scalable and transferable to other hospital systems.

Perhaps foremost is a culture in which the governing system Board of Directors prioritizes quality, safety, and patient experience over financial metrics. This sends a message to management and staff that our central purpose is to provide patient and family-centered care that is unparalleled in safety, quality, and service and innovation. This message is reinforced by an emphasis on building psychological safety in frontline staff by adherence to just culture principles and enforcement of a retaliation-free environment — where to avoid patient harm and actions such as “stop the line” are expected and rewarded.

Our hospital system has infrastructure and operational components that support large-scale improvements in standardization and high reliability. System infrastructure is led by the system chief physician executive and the Vice President of Quality and Safety, who coordinate with local entity CMO/CQOs and Quality Directors. This systemwide collaborative effort implements and monitors annually determined organizational quality and safety goals and supports unique local entity priorities. The system infrastructure includes specialized no-harm committees, and teams that are expert in data analysis, process engineering, safety, infection prevention and control, accreditation and regulatory support, and provider resiliency. Each hospital within the organization is charged with identifying and leading opportunities to eliminate unnecessary variation and is accountable to the system board for safe patient outcomes.

An accelerator of organizational learning and improvement is access to accurate safety and performance data, both favorable and non-favorable, with complete transparency among every hospital in the system. External benchmarking through Vizient, Leapfrog, CMS Star Ratings, and U.S. News Best Hospitals Ranking creates value by facilitating our ability to measure the impact of our safety strategies and function as a learning health care system.

Another important accelerator is the development of a critical mass of business- and management-trained physician leaders at each entity who align with organizational strategy and have skills in change management and operations. These physician leader champion HRO concepts of deference to frontline expertise, sensitivity to operations, situational awareness, preoccupation with failure, reluctance to simplify, and support of staff resiliency.9

A third accelerator is an innovation hub. Technology explored in the innovation hub has helped to promote the voice and expertise of frontline staff, solve challenges with clinical decision support, aid in patient risk stratification, enhance internal and external communication barriers, and expedite patient flow.

We agree that there will always be more work to do in the creation of safer hospital care, but we are determined to continue a thoughtful, intentional, and scalable approach to improvements that create meaningful changes in the lives of our patients, families, and staff. We also believe it is important to acknowledge that there are many similar efforts taking place in hospital systems throughout the country.

Eyal Zimlichman, MD, MSc

Chief Transformation Officer & Chief Innovation Officer, Founder and Director of ARC, Sheba Medical Center

Gaps in patient safety are regarded as one of the major ailments of modern health care systems. Over the past 30 years it seemed in many ways like an uphill battle, with evidence showing progress to be slow at best. The recently published study by Bates et al. has reinforced what the industry has expected and should be seen as a wake-up call to policy makers and health leaders as we pause to rethink our current approach.

To date, patient safety efforts have focused on best practices that have been shown to reduce harm, as is the case with the Central-Line Associated Blood Stream Infections (CLABSI) bundle, the Surgical Safety Checklist, and hand-off protocols. While these interventions were proven to be very effective in reducing harm, some even eliminating harm, the challenge has always been effective implementation in the real world. A good example of this challenge is portrayed in the case of the Surgical Safety Checklist, proven to decrease post-surgical mortality by almost 50% in a controlled pre-post implementation study,10 yet failing to show significant improvement in a real-world analysis.11 Similar discrepancies are typically attributable to variability in compliance with patient safety practices and have put a large emphasis on the need for a culture change to really be able to see substantial reduction in patient harm.

With our lack of significant progress in patient safety, it is time to rethink our approach: from trying harder to implement current patient safety practices, to innovation and transformation in care. As we rethink needed solutions, it is obvious that modern advances in technology, and specifically in digital health, will need to play a growing role in our new approach. Indeed, advances in areas such as big data and artificial intelligence, use of telehealth and sensors, as well as extended reality, potentially can provide game-changing solutions as we tackle this crisis. Evidence for the impact of technology has already existed for a while, like the use of decision support systems and barcoding technology to eliminate medication errors.12 Although most current decision support systems are not accurate enough and lead to alarm fatigue, upcoming systems dependent on machine learning are already showing improved performance.13 Technology will also allow us to considerably improve the safety of surgeries. Trackers in the operating room will prevent foreign body retention through alerts in real time and will not allow surgery to commence without the proper administration of pre-medications such as prophylactic antibiotics. Analytic tools will augment anesthesiologists’ ability to identify subtle hemodynamic changes and react in time. Likewise, AI-based analytics will alert surgeons during laparoscopic procedures prior to possible harm, based on recognizing anatomical landmarks.

Finally, new health delivery models could profoundly impact patient safety. One major transformative trend is the move to at-home care, with a constant shift in acute hospitalization to the “hospital at home” setting demonstrated over the past few years and gaining momentum. With mounting evidence on the effectiveness and efficiency of these models compared with traditional in-patient settings, we are finding these models safer for patients, for example by avoiding health care–associated infections.

These transformations will take time, and we are not likely to succeed on first try. Much like autonomous vehicles, initial attempts carry a risk before we see the full benefits. Still, if we are to see these transformations happen faster, we will need to take a proactive approach through a common vision, innovation and transformation ecosystems, and involving policy makers. With other challenges such as work staff shortages and burnout as well as a growing lack of resources, it seems the task will only become more and more challenging. This will require us all to turn to more transformational thinking — from “let’s try harder,” or even “we’ll be better next time,” to doing things differently. Completely differently.

With our lack of significant progress in patient safety, it is time to rethink our approach: from trying harder to implement current patient safety practices, to innovation and transformation in care.

Jonathan B. Perlin, MD, PhD

President & CEO, The Joint Commission; Clinical Professor of Health Policy and Medicine, Vanderbilt University; Adjunct Professor of Health Administration, Virginia Commonwealth University

It is hard to believe that it has been 32 years since Brennan, Leape, et al. published their groundbreaking study of adverse events, and it’s almost harder to believe that nearly a quarter century has passed since the publication of To Err Is Human.6,7 While the study by Bates et al.1 and the accompanying editorial by Berwick2 may lead one to presume that little progress has been made, I’d offer a contrarian view.

First, we have a vocabulary to address safety that was not part of the lexicon 3 decades ago. Second, that lexicon has helped us identify not only harm, but mechanisms of risk. Third, as both Bates and Berwick acknowledge, contemporary medical records allow better identification of adverse outcomes than was possible when those seminal studies were published. Lastly, it has to be acknowledged that it is nearly impossible to measure adverse events that did not occur and may even have been prevented as health care simultaneously became significantly more complex.

To contextualize, health care (and the mechanisms through which care is paid for) has changed dramatically during the last 30 years. Zidovudine, the first antiretroviral drug broadly utilized for HIV, became available in 1987; myocardial infarctions were treated by injectable thrombolytics, not stents; and cancers were not only classified by the affected organ, but also treated on that basis, compared with the molecular diagnostics and therapeutics available today. In short, even if the comparability of event detection were identical, the activity being observed is entirely different. One has to wonder whether the event rates would have been markedly worse absent the vocabulary that we have today to support performance improvement and prevent errors and close calls.

There are particular areas of medicine where performance has improved magnitudinally. Over the last half century, deaths associated with anesthesia decreased from 20 per 100,000 to less than 0.5 per 100,000.14 Also not characterized by Bates and colleagues is the survival of patients who would have succumbed to their various diseases, especially cardiovascular and oncologic. While that represents progress on the one hand, they are often far more medically complex than their predecessors. That said, just as the means of treatment have become more complex, so too has the environment for delivery of care. Oncology has transformed from a substantially inpatient disease, and now various forms of cancer are treated in the ambulatory care environment, especially infusion centers. This presents new challenges around the coordination of care. It is fair to say that emergence of cancer “navigators,” no matter how helpful to the patient traversing the system, is a response to the complexity of the system itself.

It would be tempting to say that if we just adopted a particular payment or delivery model, then all would be solved. However, notwithstanding temptations to overtreat in fee-based models, to undertreat in capitated models, and fractures in continuity across payers (especially for those without insurance or underinsured), unfortunately many similar clinical risks and similar types of adverse outcomes are observed among very different payment models. So, what can we do?

First, we have to recognize that health care as we know it is an extraordinarily complex system. Current approaches to safety assume that there is an archetype for errors, and that if we identify the archetype we can mitigate errors. Systems engineering would suggest that solutions appropriate for simple systems may not adequately translate outside of particular contexts. In other words, the general solution to an archetypical risk may not resolve the particular situation, where the lapse may be clinical, derived from discontinuities of care or, most likely, some unique combination of these factors.

Why did anesthesia enjoy magnitudinal improvement? There are likely four key reasons: First, assessment of the failure modes revealed that errors accrued from misidentification of gas lines, and a physical forcing function was introduced to eliminate the ability to attach the oxygen tube to the nitrogen port. Second, monitoring systems improved significantly and provided greater decision support for alerting the surgical team to a deteriorating patient. Third, risk stratification of patients led to better assessment of anesthetic risk, tailoring of therapy, coordination of teamwork, or even avoiding a procedure if the risk outweighed potential benefit. Fourth, the profession and industry agreed to abide by the conventions regarding tubing, utilizing advanced monitoring, and adopting risk stratification. Only one component, tubing, was in systems parlance a “simple” fix, while decision support in the form of monitoring and risk assessment and their universal professional adoption converged as solutions appropriate to a more complicated system.

So, what are the lessons for the future? First, we have to acknowledge that today’s health care is brutally complex, and simple solutions are not apt to remedy varying challenges. Parenthetically, simple solutions tend to be structural in nature, so they are a foundation upon which to build. To provide some context for the number of variables at play, it has been estimated that a critically ill patient in intensive care generates about 3,240 new data points daily and has about 300 orders in effect. Excluding interaction with the orders, 3,240 factorial results in about 1.61 to the 9969th power interactions to consider, while humans can generally manage about 7 factorial (5,040) permutations comfortably.15,16 We need help!

Kaveh G. Shojania, MD

Professor and Vice Chair, Quality & Innovation, Department of Medicine, and CQuIPS Senior Scholar, University of Toronto; Staff Physician, General Internal Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

Even without the recent study by Bates et al., it would have been surprising if preventable harms from medical care showed any improvement. No study has shown convincing reductions in adverse events over time at a regional level.17 The degree to which prominent interventions, such as the surgical checklist and central line bundle, reduce their target safety problems remains unclear.18,19 The same applies to medication reconciliation and other recommended strategies for improving medication safety. And computerized decision support has delivered mostly marginal improvements,20 while causing alert fatigue and with electronic health records (EHRs) generally contributing to clinician burnout.

The modern patient safety movement championed “system change” instead of the historic focus on individual improvement. Yet, the past 20-plus years of attention to patient safety have produced few (if any) examples of system changes — at least, not beneficial ones. Instead, we have almost exclusively seen interventions “at the sharp end,” requiring clinicians to adopt new practices and respond to report cards appealing to their professional pride and financial incentives affecting their incomes. Meanwhile, reducing “administrative harm” through better-designed institutional policies, ensuring adequate staffing, and other organizational choices at the dull end of the scalpel has received almost no attention.21

A famous quality improvement adage posits that “every system is perfectly designed to produce the results it gets.” Taking that adage seriously requires asking how it is that a field championing system change has produced so few such changes. A compelling recent commentary by the editorialist on the study by Bates et al. highlighted the existential threat posed by greed to the health care enterprise.22 The commentary pointed to monopolistic ownership contributing to stratospheric drug prices, profiteering among insurance companies participating in Medicare Advantage, and windfall profits for health care executives at the same time as we see reduced services in poor neighborhoods. Yes, one could call this greed. Yet, from a system perspective, one could call this U.S.-style capitalism working as expected. We have this same system to thank for the opiate epidemic, itself a giant patient safety problem created by commercial interests in health care. Ditto for decades of unheeded calls to prepare for pandemics given the lack of profit in vaccines — until, of course, a pandemic occurs and makes it profitable. And what other than the insidious effects of this system explain regulatory approval for hugely expensive drugs with unproven effectiveness?23 Or the 56 U.S. cities with at least one neighborhood where residents have average life spans at least 20 years shorter than residents of more affluent neighborhoods in the same city?24,25

Sadly, as several people have quipped, “most people can more easily imagine the end of the world than they can the end of capitalism.” Yet it is hard to imagine how we will effectively address any major population health problem, including the existential threat posed by the climate crisis, unless we figure out how to mitigate the deleterious effects of the profit motive on biomedical research and health care delivery. That may sound like a pipe dream. But so does calling for continued attention to patient safety without doing anything fundamentally different than we have been over more than 2 decades of efforts.26

Today, the consistent and sustained successes achieved by high-reliability organizations have not yet been reached in health care. How can this be?

Komal Bajaj, MD, MS-HPEd

Chief Quality Officer, Reproductive Geneticist, Clinical Director NYC H+H Simulation Center, Professor, Obstetrics & Gynecology and Women’s Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NYC Health + Hospitals | Jacobi | North Central Bronx

The recent article by Bates et al. spotlights what is a known troubling reality of health care delivery: the same care delivery entities that can routinely perform awe-inspiring life-improving interventions can also unintentionally cause harms. We can — and must — do better. There is no single resource or strategy that will result in harm-free care. Rather, it will take a tapestry of solutions that place patients and communities in the center through design, implementation, and assessment. It is a moral imperative for care delivery entities, payers, and policy makers alike to deliver equitable, harm-free care. Truly moving beyond a call to action to actual sustained improvements in safety will require, amongst other things, paying keen attention to psychological safety, ingraining equity into foundational patient safety processes, and harnessing learnings from all types of events.

Pay keen attention to psychological safety

Health care leaders cannot address problems or gaps they don’t know exist. A culture that promotes openness and discussion of mistakes is the only way to get better. A foundational ingredient to such a culture is psychological safety — a shared belief that it’s okay to express ideas, speak up with questions or concerns, and admit mistakes.27 A study of teams with high psychological safety demonstrated that they exceeded targets by 17%. Conversely, teams with low psychological safety on average missed targets by 19%.28 Psychological safety promotes organizational learning and can move workforces beyond post-pandemic recuperation to regeneration,29 where lessons learned from their experiences can inform safe innovations of the future.

Ingrain health equity into foundational patient safety processes

While equitable care has been a stated goal for decades, it’s clear that our structures, processes, and individual biases make it such that certain groups experience differences in access, prevention, diagnosis, and outcomes.30 For care to be truly equitable, it must be free from harm. One strategy to promote equitable care is to ingrain equity into the foundational safety processes that are already a regular part of a care delivery organization’s body of work.31 For example, as teams are identifying the root cause of an event, they must consider how structural bias or injustice might have contributed to the event. Furthermore, corrective actions to close gaps must be monitored to ensure that safe outcomes are achieved for all groups impacted (and at all hours of the day). Another strategy we have found to be extremely beneficial toward our goal of ingraining equity into foundational safety processes is to ensure that patients are part of the teams interviewing candidates for key quality and safety roles.

Harness learning from all types of events

Rightfully so, there is a tremendous amount of effort spent on learning from incidents, which are safety events that reached the patient (regardless of whether harm occurred). While we need to continue learning from these events, we must also draw insights from near misses (events that did not reach the patient) as well as events where things go exceedingly well. We’ve found that a “success cause analysis,” which mirrors methodology used during a root cause analysis, is a useful way of understanding what factors contributed to the harm-free care that must be hardwired for all. The Bates et al. article and accompanying editorial highlight the fact that comparison of events, especially across different practice settings, is fraught with challenges due to differences in what and how information is collected. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Common Formats provides a set of standardized definitions and formats to inform data collection, aggregation, and analysis for patient safety learnings across different practice environments and at different levels of levels of review.

There is not a moment to lose on the journey toward safe patient care. Our patients and health care teams deserve better.

Kris Vanhaecht, PhD, and Astrid Van Wilder, Msc

Leuven Institute for Health Care Policy, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

It was with great interest that we read Bates’ and colleagues’ latest publication in NEJM.

The paper is an important one that presents staggering numbers on patient safety and is backed by a sound methodology. Its clinical, scientific, and societal impact is clearly evident.

Four reflections resonated with us that are deserving of some elaboration.

First, the numbers presented might cause some confusion for the patient safety narrative.

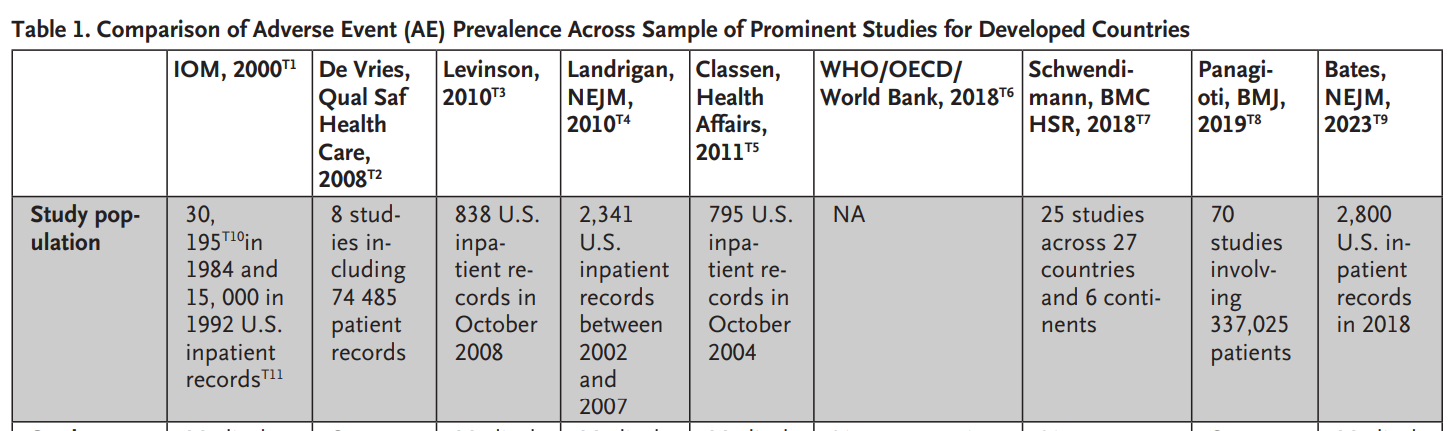

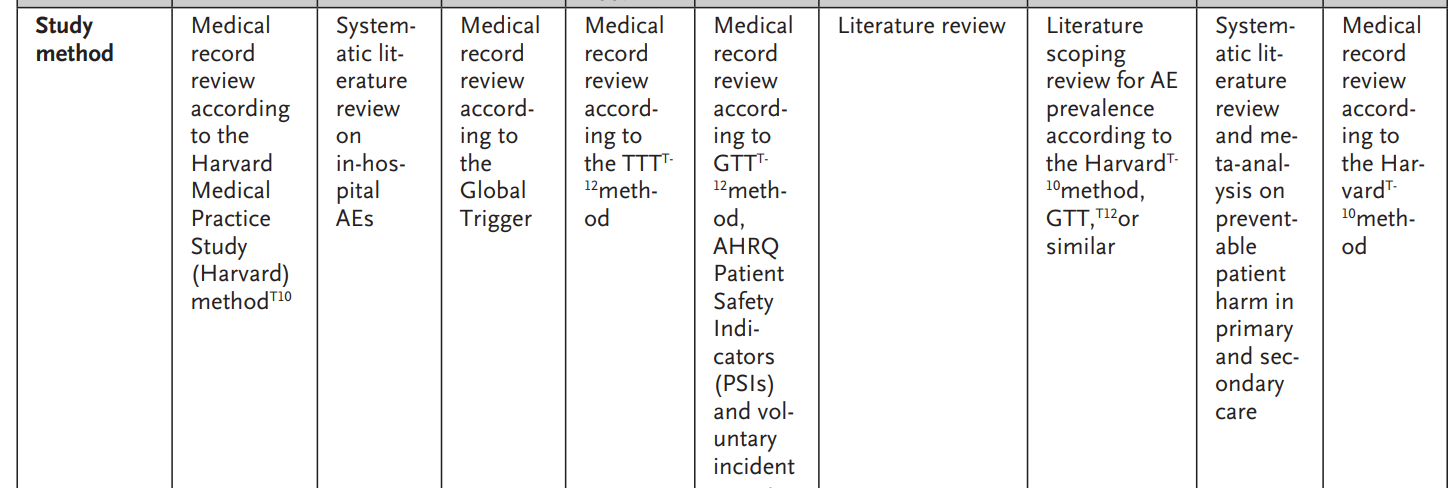

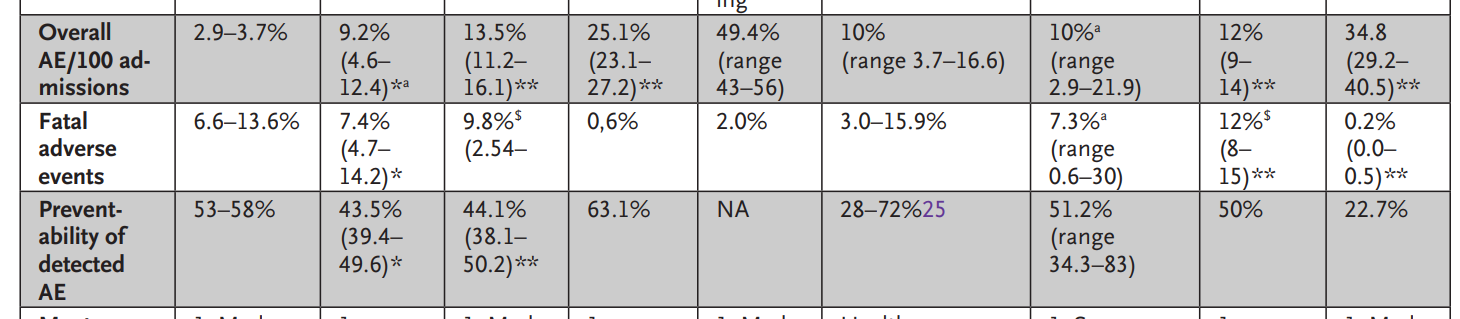

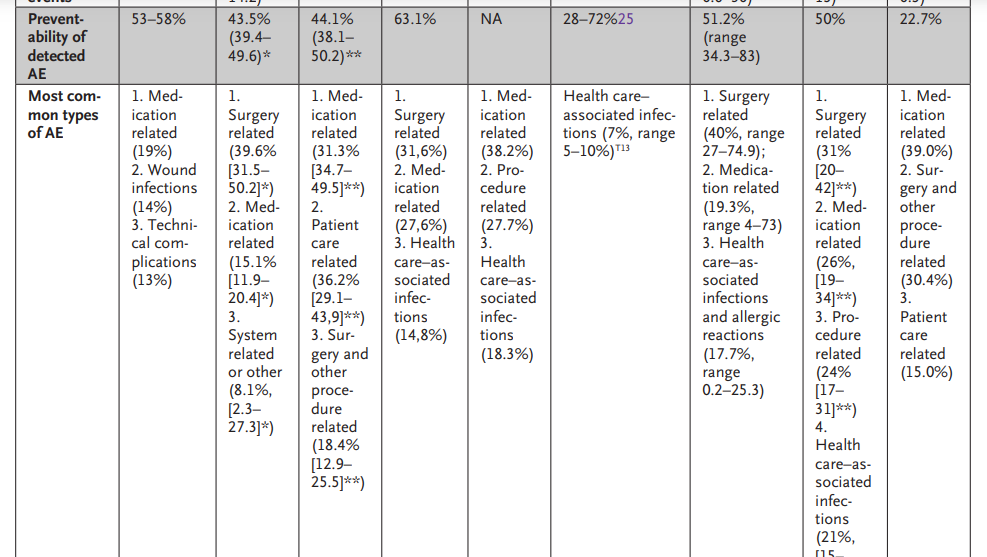

We summarized a limited sample of often-cited landmark papers in Table 1. It demonstrates how a wide range of numbers have been reported on the topic of adverse events (AEs).

How then do we translate these new results to young clinicians, hospital managers, and our patients? Do we consider them to be underestimates when comparing to the numbers of Classen et al. for example?32 Or are they overestimates when comparing to the recurring accounts of 10% of patients experiencing an AE?33–39

As accentuated by both Bates’ manuscript and Berwick’s editorial on the topic,1,2 direct comparisons of AE rates are subject to a vast set of difficulties and challenges.

Prominent differences in definitions, data collection methods, settings, and inclusion and exclusion criteria across the evidence base have culminated in an unclear and ambiguous hospital quality story.

Table 1.

Comparison of Adverse Event (AE) Prevalence Across Sample of Prominent Studies for Developed Countries

ZOOM

Second, regardless of the exact number of patients suffering from hospital-induced harm, patient safety remains an important issue within hospital care, which is Bates’ main takeaway.

We would argue that even the lowest number depicted in Table 1 is problematic.

The past 2 decades have been characterized by the development of numerous quality interventions,38 yet the most recent numbers indicate they have failed to leave a durable impact.

Continued efforts to monitor patient safety by means of continued refinements to measurement tools therefore remain required.

The heavy workload involved in manual trigger methods, along with a lack of sensitivity in certain areas, leads to the recommendation of further developing automated trigger tools39 and utilizing routinely collected administrative data.40,41

What’s more, the lack of sustainable quality improvement observed should lead to the reconsideration of quality development.

It is high time that quality of care takes into account every single health care stakeholder’s perspective, from clinicians to patients,42 and learns to cocreate a sustainable quality management system bottom-up,43 rather than imposing guidelines and quality standards top-down.

Third, Bates and colleagues only briefly touched upon the results concerning hospital variation, but as seen in Table 1, the disparities between organizations continue to be a reason for concern.

Within our quality and patient safety research group at KU Leuven, we recently published on this variation between Belgian hospitals both on a hospital-wide level41 as well as on the urological department–level.44 We discovered that variation in mortality, readmissions, and length of stay is highly prominent. Remarkably, top-scoring hospitals predominantly remained top performers over our 10-year study period, while hospitals at the bottom remained there.41 Our findings were suggestive of systemic hospital aspects influencing patient outcomes.42 Furthermore, the impact of reducing variation is presumably quite sizeable. We estimated that over 400 urological lives could potentially be saved every year in the small country of Belgium (with 11 million inhabitants) should the mortality rates of the bottom 25% of hospitals rise to the median levels of care.44 In the spirit of a Safety-II approach,45 we would encourage hospitals to engage in peer review, where top performers could help identify areas of improvement for those struggling to improve patient safety.

Finally, we’d like to zero in on an aspect that is lacking in Bates’ most recent study and is often overlooked in general.

While patient safety is without any doubt a vastly important aspect of hospital quality, it is but one factor in a complex and multidimensional system.45,46 Focus on quality of care should expand to other technical quality dimensions, such as effectiveness, efficiency, accessibility and timeliness, equity, and ecofriendliness.46 Moreover, it should recognize and remember the core values of care. Treating both care receiver and caregiver with dignity and respect, with a holistic approach, in partnership and coproduction and with well-deserved kindness and compassion, might lead toward true person-centered care.47,48 We hypothesize that acting from these core values might be the catalyst required to finally achieve genuine patient safety improvements in the future.

Leslie M. Jurecko, MD, MBA

Chief Safety, Quality and Experience Officer, Cleveland Clinic

Despite improvement efforts by many, results of studies illuminating preventative harm in health care remain largely unchanged over time. Health care systems invest in training of caregivers, technologies to aid in reliable medication administration, reporting systems to detect and hopefully correct system errors, and massive EHRs, to name just a few. Yet, there remain harm and patient suffering caused by adverse events as depicted most recently by Bates et al. Today, the consistent and sustained successes achieved by high-reliability organizations have not yet been reached in health care. How can this be?

In addition, the emotional harm patients endure from complicated access to care, unclear communication, unequitable outcomes, and lack of empathetic processes is unremitting. The waiting, the wondering, the worrying of patients goes largely unmeasured, but its undercurrent is ever-present. Sadly, emotional harm to our patients also causes moral distress to caregivers. Our job is to heal, not harm. When we watch patients as they are impacted by any of these physical or emotional harms, we too are harmed.

With other challenges such as work staff shortages and burnout as well as a growing lack of resources, it seems the task will only become more and more challenging. This will require us all to turn to more transformational thinking — from ‘let’s try harder,’ or even ‘we’ll be better next time,’ to doing things differently. Completely differently.

We often say that “hard work pays off.” But is the hard work that health care systems are individually putting in to reverse the trajectory of preventable harm paying off? Is it time for us to reach outside the walls of our tax IDs and country borders, nationally and globally, and fundamentally demand large-scale change — together? Change that is transformative, not tactical. Change that comes from within the health care industry by partnership and outside the health care industry by vulnerability, transparency, and willingness to learn. Many will contend that we have been doing this for years with collaboratives, patient safety organizations, and international think tanks. The dedication of many has been palpable, but as Bates et al. reaffirmed, it is not paying off at a scale and pace that patients and caregivers deserve.

Instead of simply asking our caregivers to care more and our health care leaders to be more accountable, let us take lessons from the pandemic, drop our perceived walls, and work together.

Some potential starting points:

1.Detect

Institute and deploy a single standard measurement system for near-miss and harm events, then go beyond that and call inequitable outcomes what they truly are — harm.

Create and commit to a standard measurement system of emotional harm caused by operational friction and poor communication.

2.Correct

Demand device safety and medication safety by our vendors and suppliers. Require human factors–integration testing prior to acceptance into our collective organizations.

Learn collectively from when things go right. Most things go right because caregivers are able to adjust their work to conditions rather than work as imagined. We likely have a lot more to learn from when things go right (then when they go wrong).

3.Prevent

Diminish health care’s “power distance” and have patients be part of the team. We need their help.

Establish a national/global health care training program that standardizes expected behaviors that all should use in the setting of health care to prevent harm reaching our patients.

Together, let us work smarter, not harder.

Tejal Gandhi, MD, MPH, CPPS

Chief Safety and Transformation Officer, Press Ganey Associates LLC

The recent NEJM article from Bates et al. titled “The Safety of Inpatient Health Care”1 is a welcome contribution to measuring the state of patient safety. The study identified that 7% of inpatients in 2018 had adverse events and 1% had serious, life threatening, or fatal preventable events. In 2022, there were 33 million hospital admissions, so these rates extrapolate to ~900 serious, life-threatening, or fatal events per day. We cannot compare this study to prior ones to say whether we are safer now than 20 years ago, because this study used more rigorous methods to identify events than prior cited studies, including trigger tools to identify events.

We have been working on patient safety for over 20 years, and I do think we have made progress, with a much stronger understanding of high reliability and known best practices for error prevention and creating cultures of safety. Yet despite these efforts, these numbers from 2018 show that safety still has not been embedded as a core value in health care.

My key takeaways from the study are as follows:

- This study is still an underestimate of the true incidence of safety events in the hospital setting (and beyond). This study shows safety event rates from 2018, prior to the pandemic. Amazing care was given during the pandemic with a goal to deliver care as safety as possible. However, data show that there have been pandemic-related backslides in safety outcomes and culture, which are not reflected in this study. In addition, diagnostic errors, though known to be common, were hard to identify using these methods. Future studies are in progress by this research group to assess ambulatory safety, and more work must be done to better understand safety issues in all the various settings across the continuum, including primary care, specialty clinics, nursing homes, dialysis centers, ambulatory surgery, hospital at home, telemedicine, and home care — just to name a few.

- This study does not include other key dimensions of harm. We need to move to a broader definition of harm, including emotional and psychological harm to patients and the workforce. Even if we are focusing on patient safety, the lack of data on emotional and psychological harm is glaring, not to mention other harms such as financial harm that can have significant impact. Going forward, we will need to have ongoing measurement and efforts focused on all of these harms in order to optimize outcomes for our patients.

- We need more robust safety measurement, using multiple sources of input. Safety event reporting from frontline staff identifies a subset of safety events and is commonly used as a primary source to identify safety issues. Safety event reporting also has benefits for driving a culture of safety by engaging staff in problem identification and identifying potential solutions. That being said, we have to expand our sources to ensure we are capturing the full range of safety events, using trigger tools, artificial intelligence, and other novel methods. In addition, we should expand such that we are more proactive — capturing risks and intervening, rather than solely measuring harms after the fact. Given innovative technologies that now exist, this is not a future dream but something that the safety field can advance now.

- There is substantial harm occurring, and leaders must ensure safety is a core value. Leaders must not get discouraged but rather refocus on safety, especially given the pandemic backslides. I know there are many competing issues such as staffing and financial pressures; however, improving safety can have multiple benefits, including positive impacts on staff retention and engagement as well as on financial performance.

- There is a clear road map to accelerate progress. The National Steering Committee for Patient Safety (which I had the honor of cochairing) released a National Action Plan for Patient Safety49 in 2020 that outlines key foundational areas of work as well as strategies and tactics for implementation. The foundational areas are Leadership and Culture, Patient Engagement, Workforce Safety, and Learning Systems, with high-reliability principles and practices embedded throughout. High reliability is the pathway to organizational resilience — the ability to bounce back from crisis. Now is the time for leaders to move to action to ensure that in the future, we can confidently say we are truly delivering safer care than ever before.

Lee A. Fleisher, MD

CMS Chief Medical Officer and Director, Center for Clinical Standards and Quality, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Professor Emeritus and Former Chair of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

The recent article by Bates and colleagues in NEJM and a recent report50 on patient safety from the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) highlighted important concerns about preventable adverse events that continue to be a major source of harm. Importantly, the studies evaluated a period prior to the onset of the Covid-19 public health emergency (PHE). Colleagues across the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and I have also reported on the deterioration of hospital quality and safety metrics since the onset of the PHE. Action is needed now, and my thoughts reflect both my role as a practicing anesthesiologist and federal policy official.

In 2000 in NEJM Catalyst, colleagues and I published a report51 on the National Quality Task Force that identified three pillars for progress, including translating best practices, developing new care models, and measuring progress locally. Lessons from the early days of the PHE highlight that knowledge dissemination and local implementation challenged many facilities in addressing the acute stressors that Covid-19 presented, with variability in mortality between different hospitals. We have facilities in this country that are delivering safe, high-quality care, which I believe is a result of having the right people, a desire to improve, and appropriate support from hospital boards and executive suites. However, the culture, people, and leadership needed to achieve these goals are not uniform across our health care system, as Don Berwick points out in his editorial.

As a result, patient safety has not improved as the health care system continues to struggle to implement the strategies we identified decades ago. Covid-19 has placed extra strain on the system, further shifting focus away from patient safety. At the beginning of the PHE, hospitals focused on ensuring access to care at the same time that clinicians and other hospital workers were concerned about their own safety. This resulted in sometimes necessary but ultimately problematic safety changes, such as rounding outside of (as opposed to inside) patient rooms and the use of a large number of agency staff. Additionally, the PHE has led to widely reported workforce burnout and workforce staffing challenges, with large numbers of new and travelling staff serving as substitutes to keep continuous care available.

Nevertheless, there is cause for optimism.

One of the hallmarks of health care safety has always been the dependence of long-standing teams and local culture coupled with a desire to improve. When I practice anesthesia, many of the staff in the operating room are now new, which can negatively impact safety. Safety in health is frequently compared to aviation, where there is relative standardization and uniformity of airplanes, communication protocols, and safety culture within any given airline, even though staff and teams rotate frequently. Aviation’s culture and standardization of procedures has evolved over decades of regulatory changes and changes to best practices, but this level of standardization and deeply embedded safety culture does not routinely exist within or across hospitals, as their equipment, processes, or communication norms are not uniform, and each culture can be unique. Additionally, patients increasingly have more challenging and complicated acuity, compounded with the continued challenge of Covid-19. As a clinician, I believe we must rethink patient safety science and best practices given the increased acuity, current staffing paradigms, and other ongoing strains on health system resources, including using the assistance of engineers, human factors experts, software architects, and organizational psychologists, among others, as anesthesiologists did when they created the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation.

As a federal policy official, I think daily about what actions CMS can take, informed by clinical experience, in developing policies that can result in safer care. CMS is committed to using all of its levers to improve the safety of individuals who are treated in facilities or programs it regulates. The past 20 years, including the PHE, have demonstrated that safety practices have not been uniformly embedded in the daily work of the health care system. First and foremost, CMS will work to ensure that a culture of safety is instilled into a hospital’s organization by hospital governance boards and leadership. CMS, including through its accrediting organizations, intends to assess whether safety culture permeates the organization, whether safety events are discussed at the board level, and how each facility organizes its quality assessment and performance improvement (QAPI) program as a means of ensuring they create the appropriate culture and accountability. Hospital boards and leadership must demonstrate the importance of safety by their actions and promote a culture of safety and transparency to the patients they serve and their community.

Second, safety is a key tenet of the CMS National Quality Strategy. As part of our work aligning quality measures across our programs and the development of the Universal Foundation of quality measures, we must ensure a robust set of patient safety metrics and look to develop new measures in gap areas such as diagnostic excellence. This will be facilitated as we support the transition to digital and data-driven health care systems, in which digital metrics can provide real-time feedback on safety precursors or events. We know many best practices to improve safety, but the key will be the local implementation within a given hospital. CMS will use its quality improvement organizations (QIOs) to aid those facilities that require the most assistance in both the implementation side of best practices and the development of the appropriate culture of safety. As we end the PHE, safety practice, safety science, and regulatory oversight must be aligned to ensure that patients are not harmed when they are cared for in our nation’s hospitals.

Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH

Adjunct Professor, Stanford University School of Medicine; Distinguished Professor Emeritus, UC Davis School of Medicine; Founding President & CEO, National Quality Forum

Notwithstanding some improvements,52 recent reviews of the state of patient safety prior to the Covid-19 pandemic make clear that preventable health care harm continues to affect large numbers of patients.50 The Covid-19 pandemic has erased many of the gains that had been made prior to 2020.53,54 The systemic transformation in health care safety that many of us had envisioned and hoped to see after the watershed events of 1995–2000 has not occurred.

In many ways, this lack of progress should not be surprising. Health care change efforts are like change efforts broadly in that two-thirds of such efforts do not achieve their intended outcomes — and a large majority of those that initially achieve their goals do not sustain the changes after 3 years. New problems, changing priorities, and loss of focus, among other things, erode the progress made by the minority of successful change initiatives.

Two things I have learned over the past 40 years leading health system and health-related change efforts are that to be successful: (1) transformation strategies must employ multiple overlapping and mutually reinforcing strategies over a prolonged period of time (the non–health care literature suggests at least 7 years); and (2) a sufficiently empowered person or entity must be in charge and accountable for the outcomes. Neither of these conditions have been fully met with patient safety writ large.

In considering what it will take to eliminate preventable health care harm, we must recognize that relying on education, behavior change, and organizational culture change to achieve and sustain improvement is necessary but not sufficient. As important as these things are, they will only get us so far. It is human nature that we can only focus on so many things at any given time, and that our attention inherently shifts to new problems as they arise. Health care has certainly had an abundance of new challenges over the past 2 decades. To support, reinforce, and back up human behavior, we need to utilize and leverage technology.

If we are to eliminate avoidable health care harm, then new safety technologies must be developed and incorporated into the processes of care. Even though medication errors remain the largest cause of preventable harm, this is also the area where the most improvement has occurred over the past 20 years, largely due to barcode medication administration. A promising technological development currently being pursued at selected health systems in the U.S. is black boxes in the operation room. And a much less grand but highly successful technological innovation developed by the VA Health Care System is the use of 3D printing to make thermal fuse covers for home oxygenators to prevent patients from removing thermal fuses that prevent fires. Other technological innovations are at varying stages of development at diverse locations. A concerted effort is needed to develop, test, and operationalize innovative safety technologies.

Also needed is a single appropriately empowered entity that “owns” and is accountable for driving desired changes in patient safety. Establishing a National Patient Safety Board modeled after the National Transportation Safety Board and Commercial Aviation Safety Team would be a big step forward in this regard.

Originally published at https://catalyst.nejm.org

Names mentioned

- Dr. Thomas H. Lee, MD, MSc, Editor-in-Chief and Editorial Board Co-Chair, NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery

- Kedar S. Mate, MD, President & CEO, Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Assistant Professor of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College

- Allen Kachalia, MD, JD , Senior Vice President of Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine; Director, Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality

- Arjun Venkatesh, MD, MBA, MHS, Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine; Chief, Emergency Services, Yale New Haven Hospital; Scientist, Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation

- Carla C. Braxton, MD, MBA, FACS, FACHE, and Shawn Tittle, MD, Chief Medical Officer/Chief Quality Officer, Houston Methodist West and Houston Methodist Continuing Care Hospitals; Associate Professor of Clinical Surgery, Houston Methodist Academic Institute; Shawn Tittle, MD, Chief Medical Officer/Chief Quality Officer, Houston Methodist Baytown Hospital

- Eyal Zimlichman, MD, MSc, Chief Transformation Officer & Chief Innovation Officer, Founder and Director of ARC, Sheba Medical Center

- Jonathan B. Perlin, MD, PhD, President & CEO, The Joint Commission; Clinical Professor of Health Policy and Medicine, Vanderbilt University; Adjunct Professor of Health Administration, Virginia Commonwealth University

- Kaveh G. Shojania, MD, Professor and Vice Chair, Quality & Innovation, Department of Medicine, and CQuIPS Senior Scholar, University of Toronto; Staff Physician, General Internal Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

- Komal Bajaj, MD, MS-HPEd, Chief Quality Officer, Reproductive Geneticist, Clinical Director NYC H+H Simulation Center, Professor, Obstetrics & Gynecology and Women’s Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NYC Health + Hospitals | Jacobi | North Central Bronx

- Kris Vanhaecht, PhD, and Astrid Van Wilder, Msc, Leuven Institute for Health Care Policy, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

- Leslie M. Jurecko, MD, MBA — Chief Safety, Quality and Experience Officer, Cleveland Clinic

- Tejal Gandhi, MD, MPH, CPPS — Chief Safety and Transformation Officer, Press Ganey Associates LLC —

- Lee A. Fleisher, MD — CMS Chief Medical Officer and Director, Center for Clinical Standards and Quality, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Professor Emeritus and Former Chair of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

- Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH — Adjunct Professor, Stanford University School of Medicine; Distinguished Professor Emeritus, UC Davis School of Medicine; Founding President & CEO, National Quality Forum