Sage Journals

Lara B. Aknin, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Elizabeth W. Dunn, Daisy E. Fancourt, Elkhonon Goldberg, John F. Helliwell, Sarah P. Jones, Elie Karam, Richard Layard, Sonja Lyubomirsky, Andrew Rzepa, Shekhar Saxena, Emily M. Thornton, Tyler J. VanderWeele, Ashley V. Whillans, Jamil Zaki , Ozge Karadag, Yanis Ben Amor

First Published January 19, 2022

Executive Summary

by Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Chief Editor of the “Health Strategy Institute” blog

Context

- COVID-19 has infected millions of people and upended the lives of most humans on the planet.

- Researchers from across the psychological sciences have sought to document and investigate the impact of COVID-19 in myriad ways, causing an explosion of research that is broad in scope, varied in methods, and challenging to consolidate.

- The authors developed the following framework: (1) Psychological distress; (2) Self-harming behavior; (3) Subjective well-being; and (4) Loneliness

Findings

Taken together, evidence collected during the first year of the pandemic points to several conclusions.

- First, repeated cross-sectional and longitudinal data sets converge to document a significant rise in psychological distress during the early months of the pandemic, which was especially pronounced among individuals who are young, female, and parents to children under 5 years of age.

- However, several sources of data suggest that most (but not all) metrics of psychological distress returned to baseline, on average, by mid-2020.

- Second, numerous sources showed no increase in suicide rates across more than 20 nations.

- Third, nationally representative data sets depicted little change, if any, in life satisfaction across most countries, with notable exceptions (e.g., Canada, United Kingdom, the United States).

- Likewise, several data sets document little to no change in loneliness.

- Finally, evidence suggests that individuals with closer proximity to illness, higher economic strain, and more household chores and childcare are at greater mental-health risk.

- Meanwhile, people report experiencing greater mental health on days when they exercise, spend time in nature, read, or volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recommendations

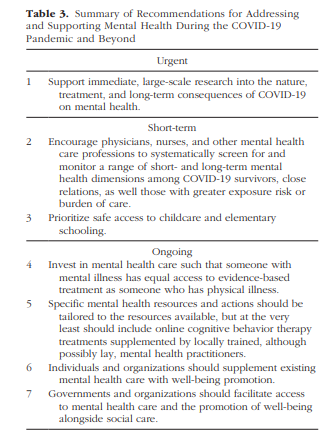

In response to these insights, we present seven recommendations (one urgent, two short-term, and four ongoing) to support mental health during the pandemic and beyond.

These recommendations aim to help people across the spectrum, from mental illness to well-being .

Urgent recommendations

- Recommendation 1. We call on researchers, governments, and funding bodies to support immediate, large-scale research to understand the nature, treatment, and long-term consequences of COVID-19 on mental health and the brain.

Short-term recommendations

- Recommendation 2. We encourage physicians, nurses, and other mental-health professionals to systematically screen for and monitor a range of short- and long-term mental-health dimensions among COVID-19 survivors and close relations.

- Recommendation 3. We recommend prioritizing safe access to childcare and elementary schooling during the pandemic.

Ongoing recommendations

- Recommendation 4. The COVID-19 pandemic offers a critical opportunity to invest in and strengthen mental-health systems to achieve a “parity of esteem,” meaning that someone who is mentally ill should have equal access to evidence-based treatment as someone who is physically ill.

- Recommendation 5. Specific mental-health resources and actions should be tailored to the resources available but at the very least should include online cognitive-behavior therapy (eCBT) treatments supplemented by locally trained, although possibly lay, mental-health practitioners.

- Recommendation 6. Individuals and organizations, including health-care providers, should supplement existing mental-health care with well-being promotion.

- Recommendation 7. Governments and organizations should facilitate access to mental-health care and the promotion of well-being alongside social care.

Conclusion

- COVID-19 poses one of the largest collective challenges of our lifetime.

- Although efforts to contain and defeat the virus have understandably been prioritized, mental health should not be ignored during the pandemic or afterward.

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely extend into the future through secondary effects on employment levels, poverty, social inequality, and more

- Widespread vaccination and the return of prepandemic life is unlikely to be immediate or fully address the mental-health patterns reported here.

- In fact, we recommend increasing attention to mental health over the next few years to prevent widening the gap between mental and physical health care, which could occur for at least two reasons.

- We encourage researchers and policymakers to continue monitoring and supporting mental health beyond virus containment and vaccination.

- Subjective well-being measurement and considerations should guide policy, both during the pandemic and beyond .

ABSTRACT (of the long version of the paper)

COVID-19 has infected millions of people and upended the lives of most humans on the planet.

Researchers from across the psychological sciences have sought to document and investigate the impact of COVID-19 in myriad ways, causing an explosion of research that is broad in scope, varied in methods, and challenging to consolidate.

Because policy and practice aimed at helping people live healthier and happier lives requires insight from robust patterns of evidence, this article provides a rapid and thorough summary of high-quality studies available through early 2021 examining the mental-health consequences of living through the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Our review of the evidence indicates that anxiety, depression, and distress increased in the early months of the pandemic.

- Meanwhile, suicide rates, life satisfaction, and loneliness remained largely stable throughout the first year of the pandemic.

In response to these insights, we present seven recommendations (one urgent, two short-term, and four ongoing) to support mental health during the pandemic and beyond.

EXCERPT (of the long version of the paper)

The text below is an excerpt of the full version of the publication “Mental Health During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review and Recommendations for Moving Forward”.

Mental Health During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review and Recommendations for Moving Forward

Sage Journals

Lara B. Aknin, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Elizabeth W. Dunn, Daisy E. Fancourt, Elkhonon Goldberg, John F. Helliwell, Sarah P. Jones, Elie Karam, Richard Layard, Sonja Lyubomirsky, Andrew Rzepa, Shekhar Saxena, Emily M. Thornton, Tyler J. VanderWeele, Ashley V. Whillans, Jamil Zaki , Ozge Karadag, Yanis Ben Amor

First Published January 19, 2022

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has infected millions of people and altered the lives of nearly every human on the planet. Although early fears focused on respiratory failure from contracting the virus, a fast-growing body of research points to the possibility that COVID-19 has a farther-reaching impact than originally recognized. Specifically, during the first year of the pandemic, most of the world’s population lived with the uncertainty of contracting the virus and with disruptions to daily life resulting from public-health measures implemented to slow the spread of COVID-19, which may have imposed psychological challenges. What are the mental-health consequences of living through a pandemic? What can individuals, organizations, and governments do to support mental health during this extraordinary time and beyond?

To help answer these questions, The Lancet assembled a COVID-19 commission to use evidence-based insights to understand the scope of the current pandemic and its consequences. This commission aims to “help speed up global, equitable, and lasting solutions to the pandemic” (Sachs et al., 2020). Part of this effort is captured in this article by the current authors, who represent the commission’s mental-health task force. Our aim is to summarize findings, delineate high-priority open questions, and offer recommendations for both individuals and organizations to support mental health during the current pandemic. We focus on mental health because it is a critical, consequential, and undersupported facet of overall well-being (Chisholm et al., 2016; Layard, 2014; Layard & Clark, 2015; Patel et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 1948). Indeed, mental illnesses affect between one third and one half of the working-age population in some countries, whereas only a small percentage of the population (~5%) receives access to evidence-based treatments that offer a favorable chance of recovery (Clark et al., 2018). Moreover, mental health holds personal, economic, and societal relevance given its greater impact on human activity than any other noncommunicable illness (Knapp & Wong, 2020) and association with higher rates of mortality (e.g., Chida & Steptoe, 2008; Howell et al., 2007; Keyes & Simoes, 2012; cf. Singer et al., 1976).

This article contains two sections. In the first section, we review the mental-health correlates of living through the pandemic using evidence collected through April 2021. In the second section, we offer seven recommendations (one urgent, two short-term, and four ongoing) and early insights for managing mental health during COVID-19 to build back better. (The White House, 2021) We call for urgent large-scale research into the nature, treatment, and long-term mental-health consequences of living through the pandemic (Recommendation 1). In the short term, we recommend more systematic monitoring of mental health for possible and confirmed patients as well as for people with higher exposure or burdens of care (Recommendation 2) and the prioritization of safe access to childcare and elementary schools (Recommendation 3). In the longer term, we encourage greater investment in mental-health services so that research-based treatment for mental health is as widely available as physical-health treatment (Recommendation 4). This includes making online mental-health therapy widely available and supplemented with in-person support (Recommendation 5); promoting widespread subjective well-being efforts at work, schools, and in communities (Recommendation 6); and embedding mental-health care and promotion within all social-care systems (Recommendation 7).

Before presenting the evidence, two limitations merit discussion. First, research on COVID-19 and its sequelae is evolving fast. Most of the evidence reviewed here was collected during the early months of the pandemic. Because the prevalence of the virus and public-health response patterns are in flux, the full picture is still unfolding. In an effort to present the most current and robust information, we focus on well-powered, representative, or weighted samples using rigorous methodologies (e.g., preregistration or well-matched control groups), including preprints that are currently undergoing peer review. We prioritized data with one or more of these qualities because such evidence is more likely to provide the most useful insights through robust estimates, generalizable conclusions, and nonspurious information. Second, much of the large-scale data available to date catalogues the impact of COVID-19 in relatively Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) nations (Henrich et al., 2010). For this reason, we are cautious about extrapolating these data to other nations and cultural contexts. More longitudinal and representative research is needed. However, we feel that several critical lessons have already emerged.

What Are the Mental-Health Consequences of Living Through the Pandemic?

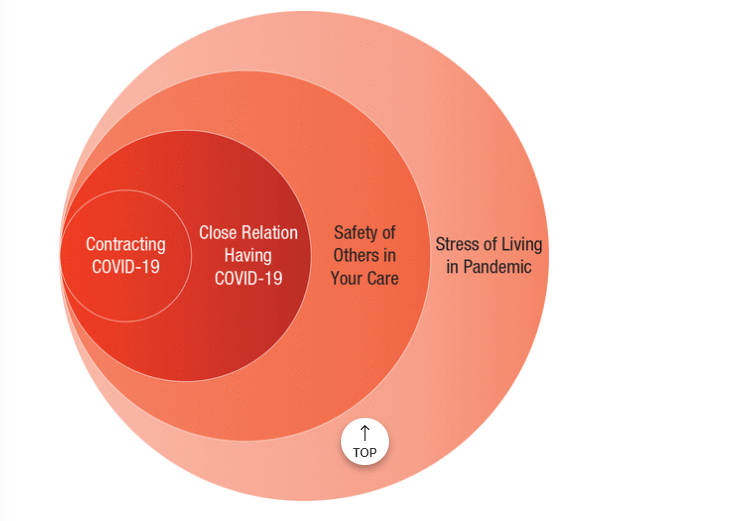

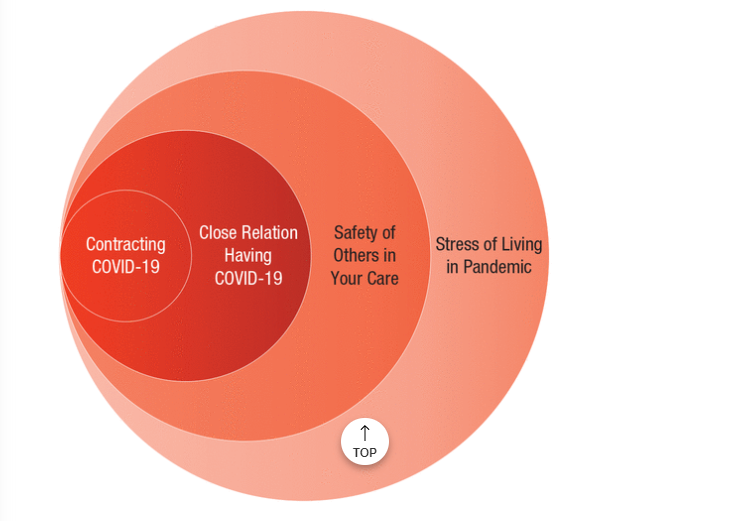

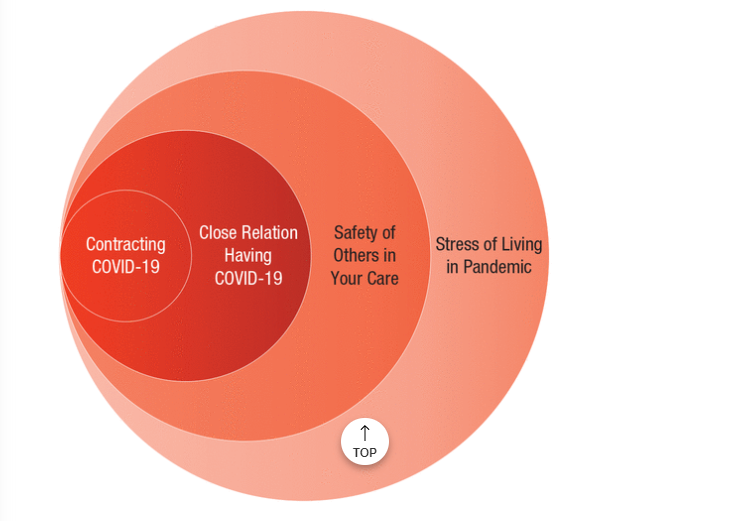

Nearly everyone on the planet has been living through the pandemic and the public-health measures issued in response, which has imposed various stressors on individuals (see Fig. 1). How has the first year of the pandemic and the wide array of response actions affected mental health? To answer this question, we first introduce mental health as a broad, complex, and multifaceted construct that we consider through the lens of four key outcomes defined below. These outcomes were chosen through a bottom-up selection process in which our multidisciplinary team of experts surveyed the literature for high-quality research in the fall of 2020 and spring of 2021. The task-force members then met to discuss and evaluate the evidence, and we identified four outcomes that had been studied sufficiently to enable initial conclusions: psychological distress, self-harm, subjective well-being, and loneliness. These outcomes represent topics that have been widely assessed and discussed during the pandemic (e.g., Clay, 2020; Miller, 2020).

Fig. 1. Stressors imposed on individuals by the COVID-19 pandemic. Each circle represents a layer of potential stress during the COVID-19 pandemic that may accumulate to undermine mental health.

Defining Our Constructs of Interest

- Psychological distress

- Self-harming behavior

- Subjective well-being

- Loneliness

Psychological distress captures a range of psychological states, including anxiety, depression, distress, and more (Kotov et al., 2017). Although many people experience low to moderate levels of these states in daily life, high levels can cause mental illness in which a person experiences severe and chronic disturbance to daily function and may be diagnosed and treated clinically by a mental-health professional (VandenBos, 2013). Here we focus on several representative constructs — mainly anxiety, depression, and distress — that have been measured in large samples with validated self-report screening and diagnostic tools, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001), to assess depression. Many of these instruments allow researchers to compute a total score that can be compared with standard cutoffs to identify acute or severe levels.

Self-harming behavior is defined here as the deliberate, direct destruction or alteration of body tissue that results in damage (Gratz, 2001). We also consider suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Although self-harming behavior is not considered a component of mental health, it is a maladaptive method of coping with overwhelming negative emotions that have harmful physical consequences and can interfere with interpersonal relationships and therapy (Favazza, 1989). Self-harm is typically measured using self-report tools, including the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001), which asks participants about the frequency with which they have been “self-harming or deliberately hurting” themselves or have experienced “thoughts that you would be better off dead” in the previous week.

Subjective well-being is defined here as the extent to which someone reports experiencing a preponderance of positive affect or emotion and infrequent negative affect or emotion, as well as a positive evaluation of their life (Diener, 1984). Because positive and negative emotions tend to be relatively malleable and respond to changes in one’s immediate environment, emotions are typically assessed by asking people to indicate the frequency or extent to which they have recently felt positive states (e.g., happy, joyful, calm) and negative states (e.g., worried, sad, bored). In contrast, life-satisfaction ratings measure respondents’ assessment of their life as a whole or its facets (e.g., satisfaction with work or family life). For instance, one tool commonly used to measure life evaluations is the Cantril ladder (Cantril, 1965), which prompts respondents to rate their life on a ladder-like scale ranging from 0 at the bottom, reflecting the worst possible life, to 10 at the top, indicating the best possible life (Helliwell et al., 2019). As this measure suggests, life evaluations tend to be more cognitive in nature (Diener et al., 2003), and although such ratings may be informed by one’s current or recent emotions, life satisfaction tends to be more stable than emotion ratings. In this article, we focus on a variety of subjective well-being measures rather than objective well-being indicators.

Loneliness is a psychological state that is associated with deficiencies in a person’s social relationships. Although loneliness is not a facet of mental health per se, a wealth of research indicates that loneliness is a key predictor of mental-health challenges, such as distress (Luchetti et al., 2020; Perlman & Peplau, 1984). It is noteworthy that mental-health difficulties arise from the perceived discrepancy between one’s desired and actual social-relationship quality rather than merely being physically isolated (Holt-Lunstad, 2017). Loneliness is often assessed using self-report measures, such as the UCLA Loneliness Scale (J. Lee & Cagle, 2017), which captures individuals’ overall loneliness, as well as their feelings of isolation and the availability of social connections. In our review, we also assess the opposite of loneliness — social connection — captured on measures such as the Social Connectedness Scale (R. M. Lee et al., 2001), which focuses more on one’s degree of connection with others and less on feelings of isolation.

With these definitions in mind, how have mental health and these related constructs changed during COVID-19?

Below we review the most informative data available to date to focus on three overarching questions (see Table 1).

First, have average levels of psychological distress, self-harm, subjective well-being, and loneliness changed from prepandemic to during the pandemic?

Second, what factors predict greater risk or protection in psychological distress, self-harm, subjective well-being, and loneliness during the pandemic onset and early months?

Third, considering data collected after COVID-19 started, what are the correlates of better and worse mental health during the pandemic?

Taken together, these questions offer a broad and useful summary of the fast-emerging literature on COVID-19 and mental health.

Table 1. Summary of the Repeated Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Evidence Surveyed to Consider How Psychological Distress, Self-Harm, Subjective Well-Being, and Loneliness/Social Connection Have Been Affected by COVID-19

See the original publication — for the table , detailed analysis and intermediary chapters

Summary

Taken together, evidence collected during the first year of the pandemic points to several conclusions.

First, repeated cross-sectional and longitudinal data sets converge to document a significant rise in psychological distress during the early months of the pandemic, which was especially pronounced among individuals who are young, female, and parents to children under 5 years of age.

However, several sources of data suggest that most (but not all) metrics of psychological distress returned to baseline, on average, by mid-2020.

Second, numerous sources showed no increase in suicide rates across more than 20 nations.

Third, nationally representative data sets depicted little change, if any, in life satisfaction across most countries, with notable exceptions (e.g., Canada, United Kingdom, the United States).

Likewise, several data sets document little to no change in loneliness.

Finally, evidence suggests that individuals with closer proximity to illness, higher economic strain, and more household chores and childcare are at greater mental-health risk.

Meanwhile, people report experiencing greater mental health on days when they exercise, spend time in nature, read, or volunteer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recommendations

The data above describe the varied, unequal, and complex changes in mental health observed in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although we have tried to synthesize the most informative studies to convey robust patterns of evidence, knowing how to respond to these insights may be unclear.

Therefore, to help governments, businesses, and individuals take action, we offer seven research-grounded recommendations (one urgent, two short-term, and four ongoing) for supporting mental health during the pandemic and beyond (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of Recommendations for Addressing and Supporting Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond

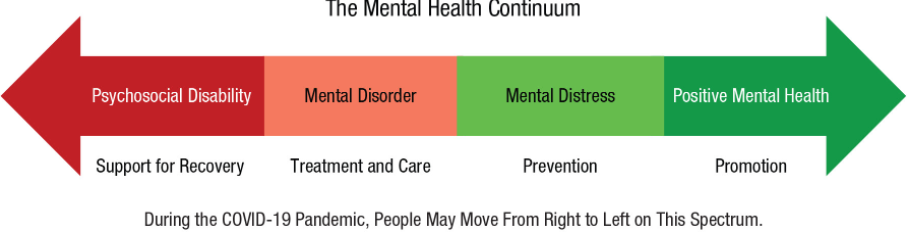

These recommendations aim to help people across the spectrum, from mental illness to well-being (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The mental-health continuum.

Urgent recommendations

Recommendation 1. We call on researchers, governments, and funding bodies to support immediate, large-scale research to understand the nature, treatment, and long-term consequences of COVID-19 on mental health and the brain (Holmes et al., 2020).

Indeed, although this article summarizes the rapidly growing and evolving evidence on COVID-19 and mental health, we do not yet know the duration and long-term impacts of this global challenge. As the number of people infected with the virus continues to climb, humanity needs greater insight into how to support those who become infected, as well as those who care for the infected (de Erausquin et al., 2020). Moreover, greater knowledge is needed to understand how most people have altered their lives, as well as what factors have supported or challenged mental health during this time. Future challenges (pandemic or otherwise) lie ahead. Increased psychological insight from this unprecedented event can help inform decision-making and policy.

Short-term recommendations

Recommendation 2. We encourage physicians, nurses, and other mental-health professionals to systematically screen for and monitor a range of short- and long-term mental-health dimensions among COVID-19 survivors and close relations.

Given the evidence above indicating that various forms of personal experience with the virus — from worries about personal safety to concern that close others have contracted COVID-19 (e.g., Wathelet et al., 2020) — are associated with greater psychological distress, public-health nurses or volunteers could follow up with patients, COVID-19 test takers, and family of those who have been ill as a result of COVID-19 to screen for psychological-distress concerns.

Early awareness of distress could trigger contact from a trained professional, who could then direct the individual to local mental-health resources.

Likewise, just as people with greater burden of care (e.g., health-care workers, teachers) and risk exposure (e.g., grocery-store clerks, factory workers) have been prioritized for physical care through early vaccination, so too should these individuals be monitored and supported with greater mental-health care (see Fig. 1).

Recommendation 3. We recommend prioritizing safe access to childcare and elementary schooling during the pandemic.

Early education and childcare provide learning, socialization, and food-access opportunities to countless children around the world, as well as intervention for safety when needed (e.g., Hoffman & Miller, 2020; Mayurasakorn et al., 2020).

In addition, elementary education and childcare allows working parents to attend to employment tasks with fewer disruptions, chores, and multitasking demands.

Thus, safe accessibility to these essential services would benefit several at-risk groups, including young women and all caregiving parents with young children (< 5 years of age) at home, who are experiencing disproportionate psychological distress and possible increases in self-harm during the pandemic (Pierce et al., 2020; Ueda et al., 2021).

Ongoing recommendations

Recommendation 4. The COVID-19 pandemic offers a critical opportunity to invest in and strengthen mental-health systems to achieve a “parity of esteem,” meaning that someone who is mentally ill should have equal access to evidence-based treatment as someone who is physically ill.

As this article demonstrates, COVID-19 led to an early increase in psychological distress, and elevated reports of depression persisted for months.

However, in a sample of 44,775 U.K. adults surveyed between late March to late April, only 40% of people reporting self-harm and suicidal ideation accessed one or more means of formal mental-health support services during the first month of lockdown (Iob, Steptoe, et al., 2020).

Likewise, only 12% of college students in France expressing psychological-distress concerns reported seeking professional help (Wathelet et al., 2020).

Given that the current concern and interest in mental health and subjective well-being might fade, we argue that now is the time to invest in mental-health services.

These services will ideally be free or heavily subsidized so that they are accessible to all.

This would help ease the burden of the pandemic and build resources so that individuals, communities, and nations are better able to handle future stressors.

Recommendation 5. Specific mental-health resources and actions should be tailored to the resources available but at the very least should include online cognitive-behavior therapy (eCBT) treatments supplemented by locally trained, although possibly lay, mental-health practitioners.

Offering universal recommendations is challenging given the range in resources (i.e., low- vs. high-income countries), as well as cultural and ethnic practices (Diala et al., 2001; Gonzalez et al., 2011).

However, several overarching suggestions emerge.

First, the physical-distancing requirements to slow the spread of the virus make online mental-health treatments an attractive and viable option.

eCBT has been shown to be effective in treating depression, anxiety, and loneliness and should therefore be widely available (Etzelmueller et al., 2020; Masi et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2019).

Second, eCBT sessions should be supplemented by occasional meetings with a therapist or local mental-health practitioner. If therapists and practitioners are scarce, community members could be trained to help with implementation and support, but care should be taken because scaling and one-off training can undermine high-fidelity treatment.

Fortunately, early data from Ethiopia, Thailand, parts of India, and the United Kingdom suggest that newly trained practitioners and even peers can be effective in task sharing when supported through community mobilization, strong leadership, awareness, stigma reduction, and support provision, as well as credit and recognition (Shidhaye et al., 2017; Singla et al., 2017; Van Ginneken et al., 2017).

Third, future research is needed to continue examining the efficacy of scaled treatment (Eaton et al., 2011), and to identify eCBT resources that are effective across cultures and available in relevant translations.

Recommendation 6. Individuals and organizations, including health-care providers, should supplement existing mental-health care with well-being promotion.

The literature on positive psychology offers a range of relatively easy, low-cost evidence-based strategies that can be implemented to increase the frequency of positive emotions and well-being (VanderWeele, 2020).

Strategies include mindfulness (Campos et al., 2016; Fredrickson et al., 2008; Grossman et al., 2004), gratitude (Davis et al., 2016), practicing kindness or generosity (Aknin et al., 2020; Curry et al., 2018; Dunn et al., 2014), and self-compassion or imagining one’s best possible self (King, 2001; Malouff & Schutte, 2017).

These tools may be especially useful during the pandemic because they target both positive and negative emotions, which people report having declined and increased, respectively, through COVID-19 (VanderWeele, 2020; Waters et al., 2021).

Thus, these practices could help bolster well-being so that people move from left to right on the mental-health continuum shown in Figure 2.

These strategies may be particularly useful because, unlike professional mental-health care, these strategies are typically brief, accessible, convenient, self-administered, and nonstigmatizing.

Although meta-analyses and/or the use of large preregistered studies support their efficacy, theorizing suggests that strategies may be more or less effective when considering features of the activity (i.e., its variety or stability), features of the actor (i.e., high vs. low motivation), and person-activity fit (see Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013).

Recommendation 7. Governments and organizations should facilitate access to mental-health care and the promotion of well-being alongside social care.

Providing citizens or employees with a list of available treatment options has not proven sufficient.

Mental-health and well-being activities should involve promotion and community outreach and be contained within the structure of a citizen’s daily life.

For instance, schools, workplaces, and community centers should include courses in positive education and positive psychology (Joyce & Paquin, 2016; Kitchener & Jorm, 2004; LaMontagne et al., 2014).

Teachers and workplace managers may be more open to these ideas now while responding to the stressors and adjustments of the pandemic, and effective models are available online (e.g., Action for Happiness).

To increase the likelihood that valuable resources reach vulnerable populations that need them most, access to and treatment with evidence-based mental-health services should be embedded within existing systems, such as social services, welfare, poverty alleviation, and social-development programs (Patel & Saxena, 2019).

Such efforts to build on existing programs and commitments (e.g., universal health coverage, other priority programs) would help to build back better and implement a whole government approach to the pandemic that affects all dimensions of our lives.

A roadmap to strengthen global mental-health systems to tackle the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been proposed and needs to be urgently implemented (Maulik et al., 2020).

Conclusion

COVID-19 poses one of the largest collective challenges of our lifetime.

Although efforts to contain and defeat the virus have understandably been prioritized, mental health should not be ignored during the pandemic or afterward.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely extend into the future through secondary effects on employment levels, poverty, social inequality, and more (Banks et al., 2021).

Widespread vaccination and the return of prepandemic life is unlikely to be immediate or fully address the mental-health patterns reported here.

In fact, we recommend increasing attention to mental health over the next few years to prevent widening the gap between mental and physical health care, which could occur for at least two reasons.

First, large-scale vaccination will require substantial investment in physical health care. Adding this to the need to reinstate routine physical care will involve significant human, economic, and coordination resources.

Second, with physical safety improving, policymakers and the public may assume that most people are prepared to return to a prepandemic routine without attending to the strains on mental health documented here.

Thus, we encourage researchers and policymakers to continue monitoring and supporting mental health beyond virus containment and vaccination.

As noted in the introduction, most of the large-scale evidence summarized in this article is drawn primarily from WEIRD nations (Henrich et al., 2010).

Although these data offer valuable early insight into how various facets of mental health and well-being are faring during the COVID-19 pandemic in the locations surveyed, nations varied widely in their initial response to the pandemic (Hale et al., 2021).

This reality requires careful consideration when trying to understand mental-health responses in lower- and middle-income countries (Kola et al., 2021) as well as global trends.

Thus, this limitation raises important opportunities for future research.

A large body of research documents the far-reaching pain caused by mental illness (Layard & Clark, 2015) and, conversely, the numerous benefits of subjective well-being (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

Thus, subjective well-being measurement and considerations should guide policy, both during the pandemic (e.g., when deciding when to impose and release government lockdowns; De Neve et al., 2020) and beyond (Diener et al., 2009; Diener & Seligman, 2004; Helliwell, 2021; Oishi & Diener, 2014; Sachs, 2019).

This refocus should help in several ways.

First, it could help to slow the spread of the virus. Recent findings suggest that happier people have stronger immune systems (Diener et al., 2017) and are more likely to comply with public-health measures, such as staying home and maintaining physical distance (Krekel et al., 2020). Indeed, recent evidence indicates that people with greater psychological distress are more likely to have missed or delayed vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic (Shapiro & McDonald, 2020).

Second, supporting happiness may target other undesirable outcomes, such as “prebunking” conspiracy theories and misinformation (Cichocka, 2020).

Finally, a greater focus on subjective well-being would bring the personal experience of citizens to center stage, necessitating ongoing and greater support to help people live fuller, more enjoyable, and connected lives.

About the authors

Lara B. Aknin, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Elizabeth W. Dunn, Daisy E. Fancourt, Elkhonon Goldberg, John F. Helliwell, Sarah P. Jones, Elie Karam, Richard Layard, Sonja Lyubomirsky, Andrew Rzepa, Shekhar Saxena, Emily M. Thornton, Tyler J. VanderWeele, Ashley V. Whillans, Jamil Zaki , Ozge Karadag, Yanis Ben Amor

References

See the original publication

Originally published at https://journals.sagepub.com