Air pollution causes over 6∙5 million deaths each year globally, and this number is increasing.

Lead and other chemicals are responsible for 1∙8 million deaths each year globally, which is probably an undercounted figure.

Health Policy Watch

Ochieng’ Ogodo

18/05/2022, [NAIROBI]

Air pollution in Mashhad, Iran. Expanding low- and middle income cities are a nexus point for risks.

While deaths from some traditional pollution sources, like domestic cookstoves and unsafe water and sanitation are declining, increased exposures to “modern” sources of pollution, such as chemicals and outdoor air pollution, mean that pollution-related mortality remains steady at about 9 million a year.

This is a key finding of a new report on “Pollution and health; a progress update”, published today by Lancet Planetary Health .

While deaths from some traditional pollution sources, like domestic cookstoves and unsafe water and sanitation are declining, increased exposures to “modern” sources of pollution, such as chemicals and outdoor air pollution, mean that pollution-related mortality remains steady at about 9 million a year.

“Modern sources of pollution such as industrialisation and urbanisation are increasingly becoming major causes of deaths but there are very little responses in tackling the [menace]from players such as donor agencies and national governments,” says Rachael Kupka, a study co-author and Executive Director of the Executive Director of the Geneva-Based Global Alliance on Health and Pollution (GAHP).

“There is also insufficient public awareness on the dangers of pollution,” she adds.

Overall, about 16% of all premature deaths annually are due to pollution, finds the study, an update of a 2017 Lancet Commission paper on pollution and health.

This also means that pollution remains the world’s largest environmental risk factor for disease and premature death.

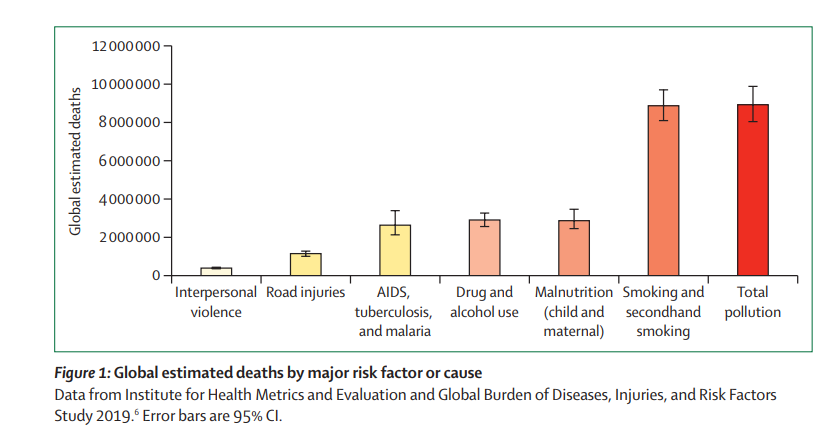

The estimates are based on the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation’s 2019 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study, which looks at a broader range of risks to health from environments, diets, lifestyles and other factors.

A comparison of the effects of pollution on morbidity and mortality with those of other risk factors on morbidity and mortality shows that pollution continues to be one of the largest risk factors for disease and premature death globally. [Editor of the blog]

The impact of pollution on health remains much greater than that of war, terrorism, malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, drugs, and alcohol, and the number of deaths caused by pollution are on par with those caused by smoking (figure 1) [Editor of the blog]

Outdoor air pollution sources now the most dangerous to health

Among pollution sources, air pollution remains the biggest killer by far, the report found — with about 6.7 million deaths in 2019 from both household and ambient air pollution sources.

However, a shift is also occurring in the balance of air pollution sources. Deaths from household air pollution, generated by the reliance of billions of people on coal and biomass cookstoves are declining gradually as households shift to cleaner domestic fuels.

But at the same time, deaths from outdoor air pollution sources have risen sharply over the past two decades — from an estimated 2.9 million deaths in 2000, when WHO first published data on mortality from air pollution risks, to an estimated 4.5 million deaths in 2019.

That increase is largely due to the continued increases in outdoor air pollution from traffic emissions, power plants and industries, in cities of the global South that are seeing explosive growth into rural areas, in unsustainable patterns of development, researchers have said, adding:

“The triad of pollution, climate change and biodiversity loss are the key global environmental issues of our time. These issues are intricately linked and solutions to each will benefit each other.”

The study also notes the deep equity fault line that pollution creates — with 92% of pollution-related deaths, and the greatest burden of pollution’s economic losses, occurring in low-income and middle-income countries.

Lead pollution still a major factor in chemical risks

The report adds that exposure to lead, a neurotoxin that also lowers IQ in children, caused 900 000 premature deaths in 2019 while other toxic chemical exposures in the workplace, accounted for 870 000 deaths.

But the figures on deaths from chemical pollutants are likely underestimates as only a small number of manufactured chemicals in commerce have been adequately tested for safety or toxicity.

Overall, deaths from the so-called “modern” pollution sources have increased by 66 percent in the past two decades, from an estimated 3.8 million deaths in 2000 to 6.3 million deaths in 2019, according to the study’s authors.

“The total effects of pollution on health would undoubtedly be larger if more comprehensive health data could be generated, especially if all pathways for chemicals in the environment were identified and analysed,” the study’s authors say.

According to Kupka, one out of five children globally is exposed to lead contamination despite the global phase out of leaded gasoline. In some countries, up to 50% of children may be exposed to lead through water piping, leaded household ceramics, lead in spices, as well as exposures in paint, artisanal mining and oil extraction and waste scavenging, according to GAHP.

Pollution has it’s biggest impacts on health in LMICS

Pollution remains the world’s largest environmental risk factor for disease and premature death, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where air pollution accounts for about 75% of the nine million deaths.

The authors are now calling for immediate action to address this existential threat to human and planetary health as, with a few notable exceptions, little efforts have been done to deal with this public health crisis.

“Pollution is still the largest existential threat to human and planetary health and jeopardizes the sustainability of modern societies. Preventing pollution can also slow climate change — achieving a double benefit for planetary health — and our report calls for a massive, rapid transition away from all fossil fuels to clean, renewable energy,” said Professor Philip Landrigan, another co-author and director of the Global Public Health Program and Global Pollution Observatory at Boston College.

This trend is more evident in Southeast Asia, where rising levels of urban pollution combine with ageing populations — who are more vulnerable to the health impacts of air pollution, and related diseases, such as heart attack, hypertension, cancers and chronic respiratory diseases.

Reduction in deaths from “traditional” pollution sources most evident in Africa

The drop in deaths from traditional pollution since 2000 is most evident in Africa, the report found. There is a decline in household air pollution as families shift away from biomass, coal and kerosene for cooking and lighting.

Household air pollution is a leading risk for childhood pneumonia deaths — along with cleaner household fuels, better medical treatment is gradually bringing that burden down. Similarly, improvements in clean water supply, storage and sanitation have reduced deaths from diarrhoeal diseases — traditionally another major killer of children under 5, the report found. Even so, lack of access to safe drinking water and improved sanitation still remains responsible for 1.4 million premature deaths every year.

Pollution prevention largely overlooked

Despite the bright spots of progress, pollution prevention is a neglected priority both among donors as well as among top officials in many of the of the low- and middle-income countries that suffer the most — including health sector leaders.

“Despite its enormous health, social and economic impacts, pollution prevention is largely overlooked in the international development agenda,” says Richard Fuller, lead author.

“Attention and funding have only minimally increased since 2015, despite well-documented increases in public concern about pollution and its health effects.”

This is despite estimates that pollution-related deaths led to economic losses totalling US$ 4∙6 trillion in 2019, equating to 6.2% of global economic output.

Intergovernmental Panel Report on Pollution

The authors called for an independent, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC)-style science/policy panel on pollution, increased funding for pollution control from governments, independent, and philanthropic donors, and improved pollution monitoring and data collection.

Approval and establishment of better connection between science and policy for pollution by international organisations.

“Prioritization of this issue by policymakers, understanding the consequences of pollution is extremely important. Ministers for environment need to ensure that pollution is factored in their national strategic plans and are budgeted,” according to Kupka.

Originally published at https://healthpolicy-watch.news on May 18, 2022.

Image Credits: Mohammad Hossein Taaghi, UN Water, Lancet Planetary Health, ISGlobal — Barcelona Institute of Global Health , DFID, Lancet Planetary Health .

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (Excerpt)

Pollution and health: a progress update

The Lancet Planetary Health

May 17, 2022

Richard Fuller, BEng

Prof Philip J Landrigan, MD

Kalpana Balakrishnan, PhD

Glynda Bathan, LLB

Stephan Bose-O’Reilly, MD

Prof Michael Brauer, ScD

Prof Jack Caravanos, DrPH

Prof Tom Chiles, PhD

Aaron Cohen, DSc

Lilian Corra, MD

Prof Maureen Cropper, PhD

Greg Ferraro, MA

Jill Hanna, MA

David Hanrahan, MSc

Prof Howard Hu, MD

Prof David Hunter, ScD

Gloria Janata, JD

Rachael Kupka, MA

Prof Bruce Lanphear, MD

Prof Maureen Lichtveld, MD

Keith Martin, MD

Adetoun Mustapha, PhD

Ernesto Sanchez-Triana, PhD

Karti Sandilya, LLB

Laura Schaefli, PhD

Joseph Shaw, PhD

Jessica Seddon, PhD

William Suk, PhD

Martha María Téllez-Rojo, PhD

Chonghuai Yan, PhD

Summary

The Lancet Commission on pollution and health reported that pollution was responsible for 9 million premature deaths in 2015, making it the world’s largest environmental risk factor for disease and premature death.

We have now updated this estimate using data from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2019.

We find that pollution remains responsible for approximately 9 million deaths per year, corresponding to one in six deaths worldwide.

Reductions have occurred in the number of deaths attributable to the types of pollution associated with extreme poverty.

However, these reductions in deaths from household air pollution and water pollution are offset by increased deaths attributable to ambient air pollution and toxic chemical pollution (ie, lead).

Deaths from these modern pollution risk factors, which are the unintended consequence of industrialisation and urbanisation, have risen by 7% since 2015 and by over 66% since 2000.

Despite ongoing efforts by UN agencies, committed groups, committed individuals, and some national governments (mostly in high-income countries), little real progress against pollution can be identified overall, particularly in the low-income and middle-income countries, where pollution is most severe.

Urgent attention is needed to control pollution and prevent pollution-related disease, with an emphasis on air pollution and lead poisoning, and a stronger focus on hazardous chemical pollution.

Pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss are closely linked. Successful control of these conjoined threats requires a globally supported, formal science–policy interface to inform intervention, influence research, and guide funding.

Pollution has typically been viewed as a local issue to be addressed through subnational and national regulation or, occasionally, using regional policy in higher-income countries.

Now, however, it is increasingly clear that pollution is a planetary threat, and that its drivers, its dispersion, and its effects on health transcend local boundaries and demand a global response.

Global action on all major modern pollutants is needed.

Global efforts can synergise with other global environmental policy programmes, especially as a large-scale, rapid transition away from all fossil fuels to clean, renewable energy is an effective strategy for preventing pollution while also slowing down climate change, and thus achieves a double benefit for planetary health.

Global efforts can synergise with other global environmental policy programmes, especially as a large-scale, rapid transition away from all fossil fuels to clean,

renewable energy is an effective strategy for preventing pollution while also slowing down climate change, and thus achieves a double benefit for planetary health.

Key messages

Over the past two decades, deaths caused by the modern forms of pollution (eg, ambient air pollution and toxic chemical pollution) have increased by 66%, ]

- driven by industrialisation, uncontrolled urbanisation, population growth, fossil fuel combustion, and an absence of adequate national or international chemical policy.

Despite declines in deaths from household air and water pollution, pollution still causes more than 9 million deaths each year globally. This number has not changed since 2015.

- More than 90% of pollution-related deaths occur in low-income and middle-income countries.

- Key areas in which focus is needed include air pollution, lead poisoning, and chemical pollution.

The main causes of the 9 million deaths each year globally are:

- Air pollution — which causes over 6∙5 million deaths each year globally, and this number is increasing.

- Lead and other chemicals are responsible for 1∙8 million deaths each year globally, which is probably an undercounted figure.

Most countries have done little to deal with this enormous public health problem.

- Although high-income countries have controlled their worst forms of pollution and linked pollution control to climate change mitigation,

- only a few low-income and middle-income countries have been able to make pollution a priority, devoted resources to pollution control, or made progress.

- Likewise, pollution control receives little attention in either official development assistance or global philanthropy.

The triad of pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss are the key global environmental issues of our time. These issues are intricately linked and solutions to each will benefit the others.

We cannot continue to ignore pollution. We are going backwards.

We cannot continue to ignore pollution. We are going backwards.

Conclusion and recommendations

Despite its substantial effects on health, societies, and economies, pollution prevention is largely overlooked in the international development agenda, with attention and funding only minimally increasing since 2015, despite well documented increases in public concern about pollution and its effects on health.

The 2017 Lancet Commission on pollution and health documented that pollution control is highly cost-effective and, because pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss are closely linked, actions taken to control pollution have a high potential to also mitigate the effects of those other planetary threats, thus producing a double or even a triple benefit.

We present specific recommendations for pollution and health, building on the earlier recommendations in the Lancet Commission on pollution and health.

International organisations and national governments need to continue expanding the focus on pollution as one of the triumvirate of global environmental issues, alongside climate change and biodiversity.

We encourage the use of the health dimension as a key driver in policy and investment decisions, using available GBD information.

International organisations and national governments need to continue expanding the focus on pollution as one of the triumvirate of global environmental issues, alongside climate change and biodiversity.

We encourage the use of the health dimension as a key driver in policy and investment decisions, using available GBD information.

Affected countries must focus resources on addressing air pollution, lead pollution, and chemical pollution, which are the key issues in modern pollution.

A massive rapid transition to wind and solar energy will reduce ambient air pollution in addition to slowing down climate change.

A massive rapid transition to wind and solar energy will reduce ambient air pollution in addition to slowing down climate change.

Private and government donors need to allocate funding for pollution management to support HPAP prioritisation processes, monitoring, and programme implementation.

ODA support should involve LMICs in setting priorities through these processes.

All sectors need to integrate pollution control into plans to address other key threats such as climate, biodiversity, food, and agriculture.

All sectors need to support a stronger stand on pollution in planetary health, OneHealth, and energy transition work.

International organisations need to establish an SPI for pollution, similar to those for climate and biodiversity, initially for chemicals, waste, and air pollution.

International organisations need to revise pollution tracking for the SDGs to correctly represent the effect of chemicals pollution including heavy metals. The reporting systems should allow burden of disease estimates to be used in the absence of national data.

International organisations and national governments need to invest in generating data and analytics to underpin evidence-based interventions to address environmental health risks.

Priority investments should include the establishment of reliable ground-level air quality monitoring networks, along with lead baseline and monitoring systems, and other chemical monitoring systems.

International organisations and national governments need to use uniform and appropriate sampling protocols to collect evidence on exposure to hazardous chemicals such as lead, mercury, or chromium, which can be compared or generalised across LMICs.

Originally published at https://www.thelancet.com