thehealthtransformation . foundation

AIHealthCare Institute

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

January 29, 2024

This is an Executive Summary of the article “AI’s Threat to the Medical Profession”, written by Agnes B. Fogo, MD , Andreas Kronbichler, MD, PhD , Ingeborg M. Bajema, MD, PhD, and published by JAMA Network — American Medical Association

Message:

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the medical profession presents both promises and perils.

While AI offers unparalleled speed, consistency, and accuracy in tasks like tissue analysis, its rapid adoption raises concerns about the potential loss of essential skills among medical professionals.

While AI offers unparalleled speed, consistency, and accuracy in tasks like tissue analysis, its rapid adoption raises concerns about the potential loss of essential skills among medical professionals.

This shift towards AI-driven medicine risks diminishing expertise, fostering reliance on automated outputs, and eroding the understanding of disease mechanisms.

Executive Summary:

The infiltration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the medical field has brought about unprecedented advancements in diagnosis and treatment.

However, the rapid integration of AI systems without thorough consideration poses significant threats to the core principles of the medical profession.

This article examines the implications of AI on the practice of pathology, using kidney pathology as a case study.

While AI streamlines processes and enhances efficiency, it also raises concerns about the erosion of essential skills among medical professionals, potential loss of intellectual debates, and the emergence of AI-defined constructs that may deviate from traditional medical knowledge.

As AI continues to evolve and permeate various medical specialties, it is imperative for physicians to strike a balance between leveraging its benefits and retaining control over the profession’s core values.

Examples and Statistics:

- Pathologists worldwide are contributing to AI algorithms by annotating tissue specimens, with up to 100,000 annotations often required for basic recognition tasks.

- The proliferation of AI tools in kidney pathology, with 27 articles followed by the release of free-to-use AI tools, highlights the rapid adoption and accessibility of AI-driven solutions.

- Despite AI’s touted consistency and unbiased performance, evidence suggests variability in algorithmic outcomes, raising concerns about overreliance on AI-generated outputs.

- AI’s ability to identify novel patterns in tissue specimens presents opportunities for new hypotheses and clinical trials but also underscores the challenge of understanding and interpreting AI-generated constructs.

Despite AI’s touted consistency and unbiased performance, evidence suggests variability in algorithmic outcomes, raising concerns about overreliance on AI-generated outputs.

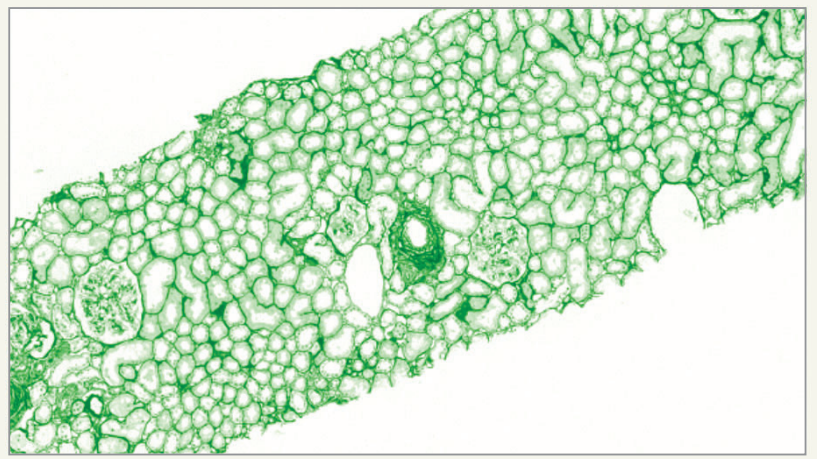

The staining symbolizes a new, not currently used stain developed for AI

purposes. EM indicates electron microscopy; GBM, glomerular basement

membrane; and IF/IH, immunofluorescence/immunohistochemistry.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

The medical profession stands at a crossroads where the integration of AI demands careful navigation to preserve its integrity and efficacy.

To mitigate the risks posed by AI’s encroachment, physicians must prioritize ongoing education, retain critical skills, and maintain active involvement in decision-making processes.

Additionally, regulatory frameworks must be established to ensure responsible AI usage, safeguard professional autonomy, and uphold ethical standards.

By embracing AI while safeguarding the essence of medical practice, physicians can harness its transformative potential while retaining control over patient care and advancing scientific understanding.

To mitigate the risks posed by AI’s encroachment, physicians must prioritize ongoing education, retain critical skills, and maintain active involvement in decision-making processes.

Additionally, regulatory frameworks must be established to ensure responsible AI usage, safeguard professional autonomy, and uphold ethical standards.

DEEP DIVE

AI’s Threat to the Medical Profession

AI IN MEDICINE

Agnes B. Fogo, MD , Andreas Kronbichler, MD, PhD ,Ingeborg M. Bajema, MD, PhD

Agnes B. Fogo, MD — Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee.

Andreas Kronbichler, MD, PhD — Department of Internal Medicine IV, Nephrology, and Hypertension, Medical University Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria.

Ingeborg M. Bajema, MD, PhD — Department of Pathology and Medical Biology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands.

The Authors Guild and 17 authors recently filed a suit against OpenAI for copyright infringement of their works of fiction on behalf of writers whose works were used to train GPT.

The complaint states that “Defendants then fed Plaintiffs’ copyrighted works into their…algorithms designed to output human-seeming text responses” and that “at the heart of these algorithms is systematic theft on a mass scale.”

How different is this situation from the developments in medicine where physicians are giving away their knowledge to artificial intelligence (AI) on a voluntary basis and spend hours of valuable research time sharing expert knowledge with AI systems.

AI has entered the medical field so rapidly and unobtrusively that it seems as if its interactions with the profession have been accepted without due diligence or in-depth consideration. It is clear that AI applications are being developed with the speed of lightning, and from recent publications it becomes frightfully apparent what we are heading for and not all of this is good.

AI may be capable of amazing performance in terms of speed, consistency, and accuracy, but all of its operations are built on knowledge derived from experts in the field.

We here follow the example of the kidney pathology field to illustrate the developments, emphasizing that this field is only exemplary of other fields in medicine.

Numerous pathologists around the world are annotating tissue specimens to feed the algorithms, and it is not uncommon that up to 100 000 annotations are needed before an algorithm can recognize basic subunits such as a glomerulus.[1]

Following this enormous effort, the algorithm will do its job in an instant.

There is the assumption that algorithms may soon be used to perform the tedious tasks that are regarded as time-consuming and not challenging intellectually, saving precious time.

It is conceivable that in the near future, pathologists will not only receive scanned slides of kidney biopsies, but that these will be accompanied by a listing that features data such as the number of glomeruli and area of interstitial fibrosis.

With this information readily at hand, the pathologist would only have to focus on the more complex lesions to generate a diagnosis (Figure).

The drawback of this situation is that if pathologists are no longer required to evaluate the basic histology elements themselves, the skill to do so will gradually be lost.

What is the disadvantage and why wouldn’t it just be time-saving and helpful to provide data in areas where we know that pathologists show a certain degree of interobserver variability anyway?[2]

It is often pointed out that a huge advantage of using AI for the evaluation of tissue slides is its consistent and unbiased performance; however, there is evidence indicating that AI algorithms also experience interobserver variability and different performance rates.[3]

One important hazard is that by moving the basic elements from the kidney biopsy literally out of the pathologist’s view, these will receive less and less attention in the day-to-day practice of clinical pathology and, thereby, the real intelligence of the basic architecture of the kidney will diminish.

In particular, in areas where an expert kidney pathologist is not available, AI-generated output may soon become the standard, accelerating the process of the AI-only situation even more.

And AI-driven pathology will be amazingly cheap. A recent review reports that 27 articles on AI in kidney pathology were followed by the release of free-to-use tools, and that this practice is spreading more and more.[4]

The advantage is a growing access for users to tools that would cost pathologists many hours of scoring.

Such tools can now be used by anyone who needs them without additional charges and with instant availability.

Legislation and regulatory requirements will probably slow down the drift toward AI-only pathology briefly, but accelerators of this process include that AI-driven pathology will be available 24/7 and will generate consistent data that are undebatable because there is no alternative expertise to form the basis for any debate.

With all these developments, it seems inevitable that we are heading toward a medical world that is essentially based on input and output.

For pathology, the input will remain a tissue sample, although the workup will change because AI does not need the traditional histological stainings to work with; it can just as well work in a stain-independent way.[5]

Output is defined by clinical measures. A very important shift in AI-driven vs human-driven pathology, based on an input-output philosophy, is encompassed by the development of AI defining areas of interest in tissue specimens through unsupervised strategies, by which a specific pixel pattern is determined that has a certain relation to clinical outcome.

An advantage may be that whereas pathologists are constrained by previously established categories and classes, the AI approach may identify certain patterns that are not yet recognized by pathologists.

By leaving out the traditional histological nomenclature and using self-learning algorithms to gather any kind of data from tissue, AI observations become surrogate markers for outcome, translating a not further defined input into an output focused on clinical decision-making only, without any knowledge of the pathogenic processes in between.

It can only be hoped that humans will be able to catch up with the newly defined constructs as long as the knowledge of real histology is still there.

For the moment, it is possible that the input-output strategy may result in new hypotheses about disease mechanisms, perhaps even allowing for proof-of-concept clinical trials.

Indeed, the current era could benefit from new ideas that AI brings because it literally is thinking “out of the box” and provides constructs that we had never thought of before.

But the other side is that if we fail to understand the processes underlying the newly defined constructs generated by AI, no logical treatment to change the correlative outcome can be developed.

The remaining question is which concept is proven in a proof-of-concept trial based on histological constructs without any meaning. Recent studies making use of unsupervised machine learning have identified tissue areas that have no names in traditional kidney pathology,[6] [7] but very little effort was made to understand them, questioning whether the new ideas and hypotheses that AI brings will be used for scientific interest or just taken for granted.

Figure. Whole Slide Image of Kidney Biopsy in Artificial Intelligence (AI) Staining Accompanied by AI-Generated Data

The staining symbolizes a new, not currently used stain developed for AI purposes. EM indicates electron microscopy; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; and IF/IH, immunofluorescence /immunohistochemistry.

We should realize that if this is allowed to move on, the near future will be characterized by rapidly decreasing knowledge about the pathogenesis underlying disease development.

Once we come to a stage where output is defined in the black box that is fed by input, and this black box contains constructs that are no longer consistent with previously defined entities, most of today’s knowledge on disease mechanisms will be forgotten and we will be ruled by systems that only focus on intervention strategies that will provide the best possible outcome.

This era will show a decrease in intellectual debates among colleagues, a sign of the time that computer scientists have already warned us about.

While authors of literature are fighting for regulations to control the usage of AI in art, physicians should contemplate how to take advantage of the potential benefits from AI in medicine without losing control over their profession.

With the issue of a landmark Executive Order[8] in the US to ensure that America leads the way in managing the risks of AI and the EU becoming the first continent to set clear rules[9] for the use of AI, physicians should realize that keeping AI within boundaries is essential for the survival of their profession and for meaningful progress in diagnosis and understanding of disease mechanisms.

Originally published at