Key recommendations — Summary

Summarized by Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Founder and CEO of “The Health Strategy Institute” in Brazil

@ The Public Health Unit

March 17, 2022

- NEW SOCIAL CONTRACT — We call for a new social contract centred on health to address Nigeria’s need to define the relationship between the citizen and the state.

- PREVENTION — We recommend that prevention should be at the heart of health policy given Nigeria’s young population.

- AMBITIOUS HEALTH REFORM — We propose an ambitious programme of healthcare reform to deliver a centrally determined, locally delivered health system.

- ENCOURAGE INNOVATION — At the same time, the system should encourage innovation.

- IMPROVE HEALTH FINANCING AND ACCOUNTABILITY — We outline options for improving health financing and ensuring better accountability and distribution of resources.

- WHOLE SYSTEM ASSESSMENT — We recommend a whole system assessment of the investment needs in Nigeria’s health security.

- DIGITISATION AND BETTER DATA STRATEGY, FUNDING AND DEVELOPMENT — We call on the Federal Government, working with state governments, to fund and lead the development of standards for the digitisation of health records and better data collection, registration and quality assurance systems.

Financial Times

March 16, 2022

Nigeria urgently needs to overhaul its health system if it is to reduce an exceptionally high burden of disease that is hampering the country’s development, according to a report by a group of global health experts.

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, has some of the world’s worst health statistics, according to Ibrahim Abubakar, dean of University College London’s faculty of population health sciences and chair of the Lancet Commission that published the report.

The commission makes the case that health lies at the core of national legitimacy and that, without it, the foundations of democratic government are shaken in a country that boasts Africa’s largest economy and is home to about one in five people on the continent.

Nigeria inherited a defective health system from the British colonial period, according to the report.

But since independence in 1960, successive governments have failed to “re-establish a social contract, including an underlying ethos and expectation of the government’s duty to provide health-creating conditions”.

Nigeria inherited a defective health system from the British colonial period,… but since independence in 1960, successive governments have failed to “re-establish a social contract,…

Nigeria, which is projected to become the world’s third-most populous country by 2050 with 400mn people, has an average life expectancy of 54, the fifth lowest in the world. Ghanaians, who have a similar standard of living, live 10 years longer.

Nigeria, which is projected to become the world’s third-most populous country by 2050 with 400mn people, has an average life expectancy of 54,

It accounts for 20 per cent of the world’s maternal deaths — those in or shortly after childbirth — despite the fact that its population of 206mn makes up just 2.6 per cent of the global population.

It accounts for 20 per cent of the world’s maternal deaths — those in or shortly after childbirth — despite the fact that its population of 206mn makes up just 2.6 per cent of the global population.

Such is the “near-absence” of records that only one in 10 deaths is registered, creating a paucity of data that makes it impossible to take rational decisions about healthcare priorities, states the report, one of the most comprehensive studies of Nigeria’s healthcare system in recent years.

It calls for the digitalisation of mostly paper-based records as a priority.

It calls for the digitalisation of mostly paper-based records as a priority.

“There’s no shortage of areas where Nigeria is the worst in the world,” said Abubakar, a professor of infectious disease epidemiology at UCL.

The report, released in Abuja on Wednesday, was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation but all the commissioners were Nigerians based at home and abroad.

Despite highlighting shortcomings in the health system, the commission argues that an overhaul of the system is feasible and affordable.

Despite highlighting shortcomings in the health system, the commission argues that an overhaul of the system is feasible and affordable.

It recommends that the Nigerian government pays for health insurance coverage for 83mn of the country’s poorest people.

Most Nigerians pay for healthcare out of their own pockets, it says, meaning that treatable diseases can have a catastrophic impact on a family’s finances.

It recommends that the Nigerian government pays for health insurance coverage for 83mn of the country’s poorest people.

Universal healthcare coverage is not impossible, the report suggests. “Countries with systems comparable with Nigeria’s, such as Ethiopia and Indonesia, have planned or implemented ambitious programmes to deliver health insurance coverage.”

Universal healthcare coverage is not impossible, the report suggests. “Countries with systems comparable with Nigeria’s, such as Ethiopia and Indonesia, have planned or implemented ambitious programmes to deliver health insurance coverage.”

The report stated that its recommendations could be partly funded by shifting costly petroleum subsidies, which it estimated at N1.5tn ($3.6bn) a year, into healthcare.

It called on the government to “establish legally ringfenced pre-determined health budgets outside of the [four-year] electoral cycle . . . to ensure sustainable funding and strategic planning”.

The report stated that its recommendations could be partly funded by shifting costly petroleum subsidies, which it estimated at N1.5tn ($3.6bn) a year, into healthcare.

Nigeria spends 4 per cent of gross domestic product on health, below the minimum 5 per cent recommended by the World Health Organization. The report recommends a substantial increase.

Nigeria spends 4 per cent of gross domestic product on health, below the minimum 5 per cent recommended by the World Health Organization.

Another of the report’s recommendations is to shift the focus of healthcare from what it calls “a dysfunctional focus on curative care” to prevention by improving access to adequate sanitation and clean water, and tackling air pollution.

Another of the report’s recommendations is to shift the focus of healthcare from what it calls “a dysfunctional focus on curative care” to prevention by improving access to adequate sanitation and clean water, and tackling air pollution.

“ This report provides a number of excellent recommendations, some of which are already being implemented but many of which we will carefully consider,” said Yemi Osinbajo, Nigeria’s vice-president, who chairs a recently convened committee looking at health reforms.

Originally published at https://www.ft.com on March 16, 2022.

Names mentioned

Ibrahim Abubakar, dean of University College London’s faculty of population health sciences and chair of the Lancet Commission that published the report.

Yemi Osinbajo, Nigeria’s vice-president, who chairs a recently convened committee looking at health reforms.

EDITORIAL @ THE LANCET

Nigeria: rightly taking its place on the world stage

Nigeria is emerging as a world power. It has great intellectual, cultural, and social capital, as well as financial assets.

It dominates west Africa, having more than half of the region’s population, and has the highest gross domestic product on the continent.

The population of more than 200 million is projected to double by 2050, and to reach 733 million by 2100 — making Nigeria the third most populous country in the world, after China and India.

This rapid population growth has been accelerated by falling infant mortality combined with a steady birth rate and can create a demographic dividend for Nigeria.

But to take advantage of this situation, appropriate investments in health, education, and skills need to be made.

Published today, The Lancet Nigeria Commission: investing in health and the future of the nation, views this human potential and extraordinary opportunity through a health lens, telling the story of Nigeria as shaped by the country’s history and present circumstances.

Written by a team of experts working at institutions across the country, and members of the diaspora, it has been led by Nigerians for Nigerians.

This potential might not be realised if the country does not address intractable poverty and extreme inequality.

Recent trends in health outcomes, as detailed in the accompanying Article published today, record 20 years of increased healthy life expectancy (although it is still low within the region, at 56 years), reductions in mortality for males and females of all ages, and rises in health expenditure but, overall, health outcomes are still poor.

Nigeria has repeatedly failed to realise the health gains promised by multiple political leaders, and this failure is holding the country back.

How can Nigerians ensure that Nigeria’s opportunity is realised? The Commissioners call for the creation of a new social contract that redefines the relationship between citizen and state.

They argue that health has, to date, been neglected by successive governments and consequently the citizens of Nigeria, and must be recentred as an essential investment in the population — one that will reap political and economic benefits.

Doing so could also help forge a new national identity, which has often been fragmented for historical reasons, beginning with its colonial-drawn borders and challenging federal system of governance.

The Commissioners propose a “One Nation, One Health” policy to attain universal health coverage, which would particularly benefit those segments of the population bearing the highest disease burden.

The Commissioners propose a “One Nation, One Health” policy to attain universal health coverage,

Acknowledging the connection between Nigeria’s citizenry and the environment and shared planetary resources, this policy could be applied at every level of governance — local, state, and national.

The Commission proposes a set of investment strategies that will have the greatest return, alongside advice on how to make best use of resources.

The two underlying principles are prevention and rational implementation, which comprise a thoughtful balance of centralisation and localisation of every policy.

The two underlying principles are prevention and rational implementation, which comprise a thoughtful balance of centralisation and localisation of every policy.

- Local governments would be empowered to deliver some aspects of health care to national standards.

- Increased financing will need to be substantial and in keeping with the growth of the country, and domestic investment will also address and reverse the inequalities that have arisen from colonial policies and foreign dependency.

- This development will also help to encourage and retain the natural talent that exists in the country.

- Human capital is Nigeria’s most valuable asset.

The Lancet

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

The Lancet Nigeria Commission: investing in health and the future of the nation

The Lancet

Prof Ibrahim Abubakar, PhD, Sarah L Dalglish, PhD, Blake Angell, PhD, Olutobi Sanuade, PhD, Seye Abimbola, PhD, Aishatu Lawal Adamu, FWACP, et al.

March 15, 2022

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

Health is central to the development of any country.

Nigeria’s gross domestic product is the largest in Africa, but its per capita income of about ₦770 000 (US$2000) is low with a highly inequitable distribution of income, wealth, and therefore, health.

It is a picture of poverty amidst plenty. Nigeria is both a wealthy country and a very poor one.

About 40% of Nigerians live in poverty, in social conditions that create ill health, and with the ever-present risk of catastrophic expenditures from high out-of-pocket spending for health.

Even compared with countries of similar income levels in Africa, Nigeria’s population health outcomes are poor, with national statistics masking drastic differences between rich and poor, urban and rural populations, and different regions.

Nigeria also holds great promise.

It is Africa’s most populous country with 206 million people and immense human talent; it has a diaspora spanning the globe, 374 ethnic groups and languages, and a decentralised federal system of governance as enshrined in its 1999 Constitution.

In this Commission, we present a positive outlook that is both possible and necessary for Nigeria to deliver equitable and optimal health outcomes.

If the country confronts its toughest challenges — a complex political structure, weak governance, poor accountability, inefficiency, and corruption — it has the potential to vastly improve population health using a multisector, whole-of-government approach.

If the country confronts its toughest challenges — a complex political structure, weak governance, poor accountability, inefficiency, and corruption — it has the potential to vastly improve population health using a multisector, whole-of-government approach.

Major obstacles include ineffective use of available resources, a dearth of robust population-level health and mortality data, insufficient financing for health and health care, sub-optimal deployment of available health funding to purchase health services, and large population inequities.

Nigeria’s demographic dividend has unguaranteed potential, with a high dependency ratio, a fast-growing population, and slow reduction in child mortality.

Effective, quality reproductive, maternal, and child health services including family planning, and female education and empowerment are likely to accelerate demographic transition and yield a demographic dividend.

This Commission was written in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has laid bare the inability of the public health system to confront new pathogens with threats to human health.

However, despite a history of weak surveillance and diagnostic infrastructure, the scale up of COVID-19 diagnostics suggests that it is possible to rapidly improve other areas with sufficient local effort and resources.

The Lancet Nigeria Commission aims to reposition future health policy in Nigeria to achieve universal health coverage and better health for all.

This Commission presents analysis and evidence to support a positive and realistic future for Nigeria.

The Commission addresses historically intractable challenges with a new narrative.

This Commission presents analysis and evidence to support a positive and realistic future for Nigeria.

Nigeria’s path to greater prosperity lies through investment in the social determinants of health and the health system.

Addressing multiple, intersecting disease burdens in a diverse population requires an equal balance between prevention and care

Nigeria’s path to greater prosperity lies through investment in the social determinants of health and the health system.

Nigeria is not making use of its most precious resource — its people — by not adequately enacting policies to address preventable health problems.

Health is influenced by access to quality health services, but other influencing factors lie outside this sphere.

Huge gains in health can and must be made by ensuring adequate sanitation and hygiene, access to clean water, and food security, especially for children, and by addressing environmental threats to health, including air pollution.

Huge gains in health can and must be made by ensuring adequate sanitation and hygiene, access to clean water, and food security …

Nigeria has a young population, yet, despite spending more on health than many countries in west Africa (mostly from out-of-pocket payment), Nigerians have a lower life expectancy (54 years) than many of their neighbours.

Nigeria’s lower life expectancy is partially due to having more deaths in children of 5 years and younger than any other country in the world, including more populous India and China and countries experiencing widespread long-term conflict, such as Somalia.

Nigeria’s lower life expectancy is partially due to having more deaths in children of 5 years and younger than any other country in the world, …

Chronic diseases and a high infectious disease burden, and an ever-present risk of epidemics of Lassa fever, meningitis, and cholera, present additional challenges.

Chronic diseases and a high infectious disease burden, and an ever-present risk of epidemics of Lassa fever, meningitis, and cholera, present additional challenges.

A rising population and inadequate infrastructure development over the past 30 years have contributed to increasing deaths from trauma through road injuries and conflicts driven by inequitable distribution of resources.

Addressing Nigeria’s health challenges requires a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach to prevent ill health.

This means investing in highly cost-effective health-promoting policies and interventions, which have extremely high cost–benefit ratios, and offering clear political benefits for implementation.

Interventions are needed to

- improve child nutrition,

- reduce indoor and outdoor air pollution,

- address unmet family planning needs, and

- improve access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

Addressing Nigeria’s health challenges requires a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach to prevent ill health.

Interventions are needed to: improve child nutrition, reduce indoor and outdoor air pollution, address unmet family planning needs, and improve access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

Governance and prioritisation of health are the first places to start

We call for the thoughtful use of existing institutions as an approach to achieve better governance and prioritisation of health.

Although corruption has undermined the Nigerian health system, we can harness existing institutions for the benefit of population health.

Although corruption has undermined the Nigerian health system, we can harness existing institutions for the benefit of population health.

All levels of Government in Nigeria (federal, state, and local), and traditional leadership structures, civil society, the private sector, religious organisations, and communities, influence health.

Efforts towards a balance between centralisation and localisation should focus on common policies, standards, and accountability.

Concurrently, there is an equal need for localisation of implementation, meaning actual community and local government ownership of health service delivery.

All three levels of Government are crucial, and we provide recommendations for each level.

Differences in regional needs and context must also dictate programmes and interventions. What is needed in the northeast, in a context of ongoing insecurity and a crisis of internally displaced persons, is quite different from needs in wealthier, more secure urban centres, or in the face of the different level of insecurity found in oil-producing areas in the Niger Delta.

Prioritisation of health requires additional funds. We have provided a clear investment case on health to convince politicians and governments that improved population health will reap political, demographic, and economic dividends.

Our call for a whole-of-government approach to health will allow the delivery of multisectoral policies to address the social determinants of health, prioritise health-care expenditure to major causes of burden of diseases, and substantially increase healthy and productive lifespans.

Leapfrogging the health system into the 21st century

Nigeria’s health system was built in an ad hoc way, layering traditional community health systems with colonial medicine aimed at maximising resource extraction.

This origin has resulted in inbuilt inequalities, a dysfunctional focus on curative care, and a detrimental social distance from users and communities. Post-independence policies to redress problems have only been partially implemented.

However, the current health system is sprawling, multifarious, disintegrated, and frequently inaccessible, with very minimal financial risk protection and low financial accessibility of services.

Nigerians variously seek care from medical personnel and auxiliaries, community health workers, medicine vendors, marabouts and spiritual healers, traditional birth attendants, and other informal providers.

The system relies on a mixture of quasi-tax-funding, fee-for-service, and minimal health insurance coverage.

What kind of health system do Nigerians deserve, and should the country’s leaders work towards?

The core need of most Nigerians today is for accessible basic health services, and for this to be achieved, improvements in public sector delivery supported by an enhanced complementary private sector, including faith-based organisations, is the way forward.

We lay out a path for Nigeria to move towards a system that, although remaining diverse, better serves the needs of the population.

Within this diversity, we believe there is an opportunity for a “one nation and one health” approach, whereby Nigeria guarantees a minimum standard and delivery of health care for all with an emphasis on strengthening public and private (including faith-based and non-profit) systems.

… we believe there is an opportunity for a “one nation and one health” approach — whereby Nigeria guarantees a minimum standard and delivery of health care for all with an emphasis on strengthening public and private (including faith-based and non-profit) systems.

Nigeria should also leverage the private sector for certain functions, such as expanding innovation, discovery, and manufacturing capacities to claim a leadership role on the African continent and globally.

Government investment in private industry should be mission-driven, supporting innovation and claiming dividends for society from its investments.

Nigeria should also leverage the private sector for certain functions, … Government investment in private industry should be mission-driven …

Core functions of the health system require immediate attention, in particular, good quality health data.

This Commission strongly recommends better recording, storage, and use of data. Paper systems are unworkable.

A drive towards digitisation can result in major improvements, for both patient care and devolved health decision-making.

Mobile digital technologies should allow a relatively rapid expansion of population health data and linked existing datasets.

Human resources in rural and poor regions of the country are worsened by brain drain. We propose prioritising the optimal development and redistribution of health workers at all levels.

Core functions of the health system require immediate attention, in particular, good quality health data.

Financing health for all by rationalising contributions from insurance, out-of-pocket payments, donor funding, and taxes

A viable health system requires dedicated, efficient, and equitable health financing mechanisms, complemented by optional health insurance.

Countries with systems comparable with Nigeria’s, such as Ethiopia and Indonesia, have planned or implemented ambitious programmes to deliver health insurance coverage.

A viable health system requires dedicated, efficient, and equitable health financing mechanisms, complemented by optional health insurance.

Nigeria’s public health system should be supported by a comprehensive health insurance system for all people, funded using through both contributions and taxation, with trials underway in states such as Anambra.

Access to health insurance for society’s most vulnerable people must be government funded. Considerable political will is needed to bring a greater proportion of the informal sector accessed by most Nigerians under government governance mechanisms.

Nigeria’s public health system should be supported by a comprehensive health insurance system for all people, funded using through both contributions and taxation, with trials underway in states such as Anambra.

Access to health insurance for society’s most vulnerable people must be government funded.

There is also a need to expand the fiscal space by increasing overall government revenue, which will lead to higher health funding, allowing health and the determinants of health to be addressed.

Achieving these financing goals will require an optimistic political economy approach, considering current context, alongside future steps. A starting point could be explicit declaration by governments at all tiers that the achievement of universal health coverage is a priority goal.

Nigeria is a country with so much wealth in terms of human talent and potential, but also beset by challenges, including inadequate provisions for optimal health-care delivery and well-being of its people. For Nigeria to fulfil its potential, the leaders and people alike must embrace the implications of what they know already — that health is wealth.

Key messages

- We call for a new social contract centred on health to address Nigeria’s need to define the relationship between the citizen and the state. Health is a unique political lever, which to date has been under-utilised as a mechanism to rally populations. Good health can be at the core of the rebirth of a patriotic national identity and sense of belonging. A commitment to a “One Nation, One Health” policy would prioritise the attainment of Universal Health Coverage for the most vulnerable subpopulations, who also bear the highest disease burden.

- We recommend that prevention should be at the heart of health policy given Nigeria’s young population. This will require a whole-of-government approach and community engagement. An explicit consideration of equity in the implementation of programmes and provision of social welfare, education and employment opportunities should be paramount.

- We propose an ambitious programme of healthcare reform to deliver a centrally determined, locally delivered health system. The goal of government should be to provide health insurance coverage for 83 million poor Nigerians who cannot afford to pay premiums. Implementation of a reinvigorated National Strategic Health Development Plan (NSHDP III) should be supported by structured and explicit approaches to ensure that Federal, State and Local Governments deliver and are held accountable for non-delivery. NSHDP III should be supported by a ring-fenced budget and have a longer horizon of at least a decade during which common rules should apply to all parts of the system.

- At the same time, the system should encourage innovation. Future health system reform should engage communities to ensure that existing nationally driven schemes have local buy-in and are sustainable. Further, since more than 50% of health services are provided in the private sector, often with poor quality and high costs, reforming the policy and regulatory landscape to unleash the market potential of the private sector is important.

- We outline options for improving health financing and ensuring better accountability and distribution of resources. The rationalised governance schemes we have proposed should improve the efficient use of existing resources devoted to health. Ultimately, the proportion of spending allocated to health needs to be increased. We envision a future of Nigeria’s health without foreign aid. This will require substantial increase in domestic investments. Foreign aid (multilateral, bilateral, and philanthropic) has led to fragmentation of the already complex health development landscape, with huge asymmetries in legitimacy between foreign actors and the Nigerian state as well as weak accountability. Defragmenting and decolonizing the Nigerian health landscape requires domesticating health financing.

- We recommend a whole system assessment of the invest-ment needs in Nigeria’s health security. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the weaknesses of Nigeria’s health security system. Nigeria needs better manufacturing capacity for essential health products, medicines and vaccines, the provision of diagnostics, surveillance and preventive public health measures in health facilities and community settings, as well as other preventive and curative measures.

- We call on the Federal Government, working with state governments, to fund and lead the development of standards for the digitisation of health records and better data collection, registration and quality assurance systems. A National Medical Research Council with 2% of the health budget and central government funding to award competitive peer reviewed grants will support high quality evidence and innovation.

EXCERPT OF SECTION 5

Section 5: investing in the future of Nigeria — health for wealth

Prosperity, macroeconomics, and health

The total GDP of Nigeria was estimated at $448 billion in 2019. 181

Five sectors are the major contributors to Nigeria’s GDP with the largest being agriculture contributing about 24·5% to the total nominal GDP in 2020, 182 followed by trade at 13·9%, manufacturing at 12·8%, information and communication at 11·2%, construction at 7·6%, and mining and quarrying at 7·1%. 182

The GDP per capita was US$2230 in 2019, 183 the per capita total health expenditure was $72·7 and the proportion of total health expenditure relative to GDP was 3·6% in 2018.184

Moreover, most of this expenditure was private with public spending as a percentage of total health expenditure constituting only 16·3%, whereas private spending as a percentage of total health expenditure was 76·6% and out-of-pocket spending as a percentage of total health expenditure was 74·9%.184

External resources as a percentage of total health expenditure was 7·7%.184

Total health expenditure as a percentage of GDP has remained between 3·4% and 4·1% since 2006 (figure 7).

Nigeria hosted and signed the 2001 Abuja declaration,185 in which African governments committed to allocate at least 15% of government spending to health. The low levels of total health expenditure to GDP ratio and public spending on health, and the heavy burden of disease shows that it is important that overall health expenditure is increased. Without an increase in total health expenditure to GDP ratio, only an increase in GDP will lead to a rise in total health expenditure (from all sources, most currently being out-of-pocket). Nigeria should concurrently increase its GDP, the overall fiscal space, and the proportion of the budget allocated to health as outlined further on in this Commission.

Concerted advocacy and community engagement efforts from committed and powerful national and state-level institutions and civil society organisations could push health (including harm-reduction and pro-health multisectoral policies) and health-care funding up the political agenda, making it a key election issue. In subsequent elections, holding politicians to account at the ballot box for their previous promises to improve health and access to healthy environments, could engender sustained progress. The COVID-19 pandemic and other health security risks could present the opportunity to increase this advocacy through political engagement. The investment case for health spending in Nigeria is clear; health spending provides value for money and can be politically rewarding.

The investment case

Value for money

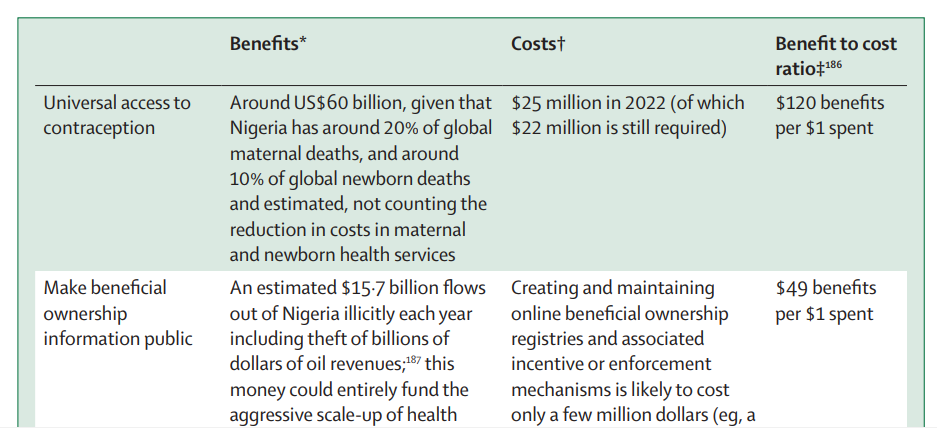

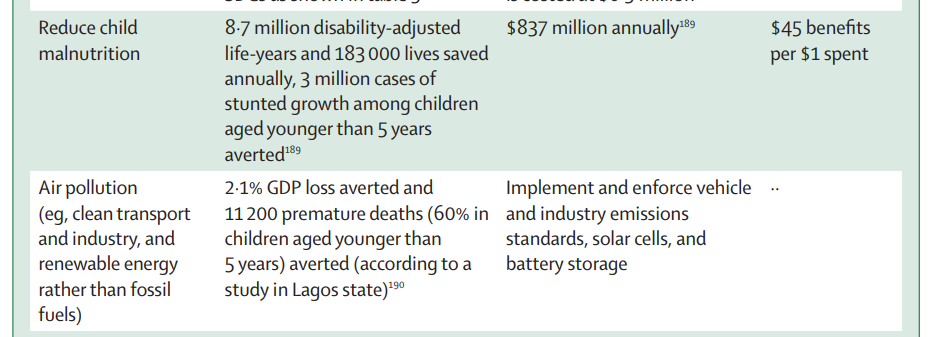

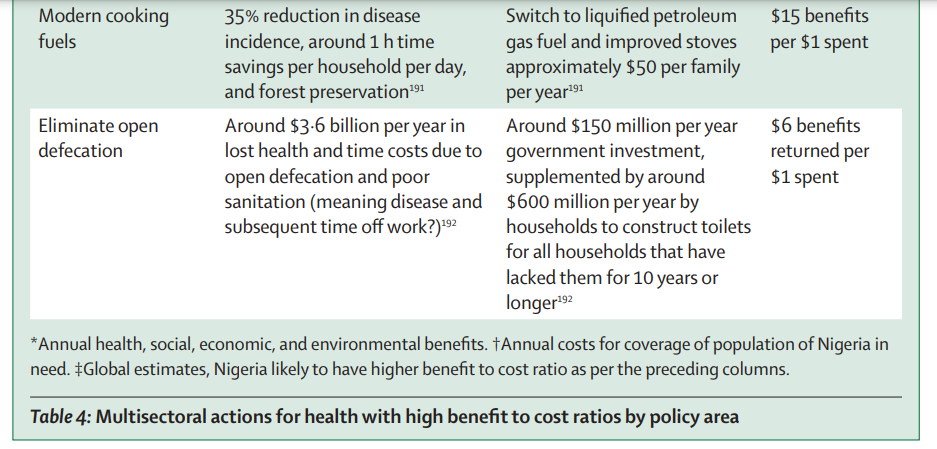

Spending existing revenues in ways that efficiently and equitably decrease the burden of disease to in turn reduce health-care need is crucial, as is direct investment in multisectoral action to prevent disease (table 4) and better strategic purchasing in the health sector to improve diagnosis and treatment.

Table 4: Multisectoral actions for health with high benefit to cost ratios by policy area

EXCERPT OF SECTION 6

Section 6: conclusions and recommendations

With Nigeria’s large and growing population, ongoing governance and security challenges, and potential leadership role in Africa and globally, the decisions made today will determine whether Africa’s most populous country will become a success story or a cautionary tale.

A successful Nigeria will inarguably require strong investments in health, education, and basic public services, following a central organising principle of creating a healthy population (ie, a health-in-all-policies approach).

Such an approach is the best pathway to human flourishing, economic development, and a legacy for the politicians who achieve it.

The strength of institutions — in government, civil society, traditional and religious authorities, and within communities — can and must be harnessed to engender and reap the benefits of a virtuous cycle of prosperity and good health.

Institutions, including formal structures such as the constitution and laws, and informal societal factors such as customary norms and values, are requisite to achieving the political and social accountability that continues to elude the nation.

The alternative of business-as-usual risks a spiral of increasing poverty, inequality, and insecurity as the growing population is blighted by the interdependent challenges of lack of opportunity, poor education, and poor health.

Delivering a health agenda for Nigeria is thus a matter of the utmost importance for Nigeria, the subregion, and the world.

In this Commission, we began by exploring how Nigeria’s health system, writ large, evolved from a widely accessible community health infrastructure during the pre-colonial period, to an inegalitarian colonial inheritance, ultimately leading to a post-independence period of an unequally distributed, unbalanced, and weak health system despite multiple national plans over six decades.

Nevertheless, the story of the Nigerian health system presents numerous successes that can serve as lessons to build upon.

The overall progress over the past 50 years shows that most indicators have moved in the right direction, although there is much room for improvement.

Further, Nigeria effectively utilised vertical programmes with international multilateral agency support to contain Guineaworm disease and wild-type poliomyelitis showing that the health system can, in particular circumstances, deliver.

There is a distinct opportunity to fulfil Nigeria’s constitutional promise to ensure health care to all persons and extend this to wider preventive health goals.

The giant of Africa — Africa’s largest country in terms of population and economy — enjoys considerable unrealised potential.

The time to achieve greatness is now, with health at the heart of the development agenda.

The health system can become a positive reflection of Nigeria — with successful health reform the catalyst to show why Nigeria matters to Nigerians, giving good reason for patriotism, and serving as a model for wider societal change.

Contributors

The Lancet Nigeria Commission was chaired and led by IA and coordinated by SLD with support from a writing group (OS, BA, TC), and working group leads. The work for the Commission was undertaken in five subgroups and all commissioners met in person in London in 2020 and several times online in 2020 and 2021. Work stream leads provided sections of the report in the following areas: introduction (IA), history (FO, ETO, and AOO), disease burden (IA and IMOA), vision (AE and SLD), health system (SA), and finance (OO and TC). BA and OS contributed to the collection and analysis of disease burden, health system, and health financing data. All authors read and critiqued the manuscript and approved the final version of the Commission. The first full draft of the report manuscript was written by IA and SLD with input on subsequent drafts by all authors. All commissioners participated in creating Commission content, shaping the overall Commission structure, writing and editing drafts, and formulating conclusions and recommendations. All authors had full access to all the data in the report and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this Commission and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.