Wasting with intention: Fraud, abuse, corruption and other integrity violations in the health sector

by Agnès Couffinhal and Andrea Frankowski

This is an excerpt of the report “Tackling Wasteful Spending on Health”, published by OECD in 2017.

Executive Summary

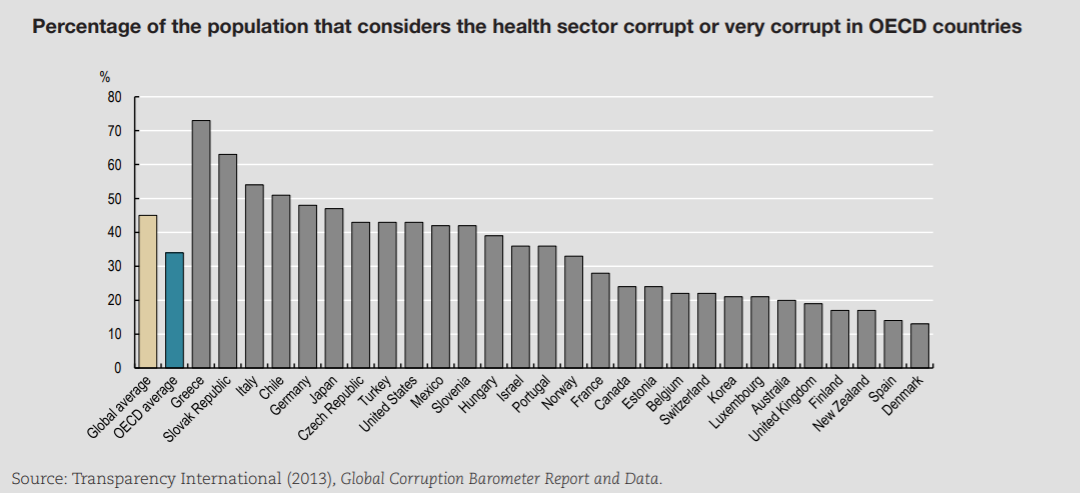

A third of OECD citizens believe the health sector is corrupt or very corrupt, with large variations across countries.

Strategies to detect, prevent and address fraud in the delivery and financing of care vary:

- Some countries assign the responsibility to health sector institutions (e.g. Australia, Belgium) or payers (France), others rely on general anti-fraud bodies (Austria, Slovenia).

- Fraud detection can rely on simple audits and/or the investigation of complaints. Hotlines can encourage the reporting of integrity violations (e.g. Australia, the United States). More advanced countries use analytical tools including data mining (France).

A stepwise, comprehensive and credibly enforceable approach to suspected fraud or abuse response works best. Efforts must go into engaging health professionals, recognising that errors can happen and that special circumstances can prompt deviations from good practices. Efforts can pay-off: For example in the United States, between 2013–15, USD 6.1 was returned for every USD 1.0 spent on fraud and error detection.

Tools to curb inappropriate business practices in the health sector include limits or bans on specific activities that are at too high a risk of generating inappropriate behaviours. This is the case for dispensing of medicines by physicians (Australia, France), self-interested referrals by and kickbacks to health providers (United States, Slovenia, Poland).

More transparency in the financial relationships between industries and health care providers is increasingly promoted by self-regulation (European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations code of conduct) as well as Sunshine-type regulations (requirements that payments made by industries to stakeholders be systematically reported to authorities). In the United States, industries must report relationships with physicians and teaching hospitals. In France disclosure covers ties with all health professionals and associations representing them, scientific societies, patients’ associations and the press.

Self-regulation by providers, professional associations, and business remains the norm but its effectiveness is not thoroughly assessed.

Key messages

The final category of waste reviewed in this report essentially comprises resources illegitimately and deliberately diverted from health care to serve the self-interest of a few. From the report’s perspective, it is easy to conceptualise these integrity violations as wasteful. The chapter reviewed actions taken to reduce fraud and abuse in service delivery and financing as well as strategies put in place by countries to prevent inappropriate business practices in the sector.

Integrity violations in health, as in any sector of the economy, are notoriously difficult to measure and compare across systems. A first reason is lack of a uniform understanding of what may constitute fraud, abuse and corruption. More importantly, since most activities are reprehensible and some at least can be sanctioned, they naturally tend to be covert. Nevertheless:

- A third of OECD citizens deem the sector as corrupt or extremely corrupt (45% globally).

- The loss to fraud and error combined is an average 6% of related health expenditure, with most estimates ranging between 3% and 8%. Countries differ significantly in the level of effort they put into addressing integrity violations in service delivery and financing.

- The response is primarily organisational in that it involves assigning responsibility for detecting or tackling integrity violations in service delivery and financing to specific institutions and sometimes defining how it will be done.

- Fraud detection activities can be more or less pro-active. They can rely on simple audits, controls and/or the investigation of complaints, and systems may or may not be in place to encourage the reporting of integrity violations — for instance through hotlines. More advanced countries use analytical tools to detect integrity violations, including data mining.

- Practitioners highlight the importance of having a stepwise, comprehensive and credibly enforceable response. Overall, efforts must go into engaging and communicating with health professionals, recognising that errors can happen and that special circumstances can dictate deviations from good practices.

The need to tackle inappropriate business practices in the health sector is gaining increasing attention:

Responses by countries are typically regulatory in nature and consist of limiting or banning certain practices.

Little attention is paid to actively detecting these types of integrity violations. Instead, countries rely on whistle-blowers reporting integrity violations or the investigation of and reaction to specific crises, particularly when they have detrimental consequences on health.

The three main domains where some countries have introduced regulation seek to limit self-interested referrals by health providers and the means by which the pharmaceutical industry is allowed to promote sales — including Sunshine-type regulations. The question of how to ensure the integrity of research, particularly when it comes to clinical trials and CoI, is also gaining traction.

- Self-regulation by industry remains the norm, nonetheless.

Overall, many OECD countries need to strengthen their efforts to curb integrity violations in health, not only to reduce waste and increase efficiency, but to enhance transparency, improve the integrity of the sector and contribute to patient safety as well.

Presentation

This chapter discusses fraud, abuse, corruption and other integrity violations that divert resources from the health care system and as such are wasteful. The first section explains why the health sector is prone to integrity violations and gathers evidence on the scale of the problem in OECD countries. The second section analyses in more details integrity violations in service delivery and financing and reviews how OECD countries detect, prevent and tackle them. The third section points to the most common inappropriate business practices observed across health care systems and maps some of the regulatory and self-regulatory approaches used by countries to limit such practices.

Julien Daviet conducted the initial bibliographic research and analyses of the Eurobarometer and Transparency International surveys. Valuable comments and insights were provided on earlier drafts by Paul Vincke, Managing Director of the European Healthcare Fraud and Corruption Network; Ruth Lopert, Deputy Director, Pharma Policy & Strategy, Management Sciences for Health; and Sophie Peresson, Director, Pharmaceuticals & Healthcare Programme, Transparency International UK. We thank the respondents to the questionnaire and delegates for their comments on the draft and suggestions, in particular during the expert meeting of 8 April 2016, and the OECD Health Committee meeting of 28–29 June 2016.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in theWest Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

Situations in which resources are misspent or spent inefficiently reviewed in this report so far are, for the most part, the unintended consequences of the way health care systems are organised and human factors, sometimes driven by poor incentives. In contrast, the behaviours reviewed in this chapter all have in common that the actors engaging in them deliberately divert resources from the health care system in their own self-interest or in the interest of a group they support.

Numerous terms are used to describe these behaviours and their many variations — including fraud, corruption, abuse, collusion and traffic in influence, among others. To avoid a semantic debate, they are simply coined resource-diverting and intentional “integrity violations” here. They prevail in all OECD health care systems and are multifaceted. These behaviours take place in the context of:

- a vast array of transactions involving providers of health services, payers of these services, and/or recipients/consumers

- the procurement and distribution of medical goods and services

- the promotion of corporate/industrial interests in the health sector.

The following section sets out the problem of integrity violations in the health sector. Subsequent ones reflect on the experiences and approaches of OECD countries in dealing with the two main categories of integrity violations in health care systems for which health-specific policies or regulations are in place: integrity violations in financing and delivery as well as inappropriate business practices.

1. Setting the scene: Why worry about fraud, abuse and corruption?

A number of theoretical and ethical considerations explain why the health sector might be prone to fraud, abuse and corruption (Section 1). Despite the challenges inherent to measuring the costs of corruption, existing data suggest that it is prevalent in OECD health care systems (Section 2). To learn from countries’ experience in preventing, detecting and tackling fraud, abuse and corruption, a framework is developed to map the various integrity violations that divert resources from their intended use in the health care system (Section 3).

1.1. Why would fraud, abuse or corruption be present in health care systems?

Perhaps more than in other industries or sectors, the nature of the health care system’s core objective to improve human health and potentially save lives may create expectations that stakeholders are bound to behave ethically. In reality, a number of theoretical reasons suggest that the sector is particularly vulnerable to corruption, with consequences that are not only financial.

A number of considerations suggest that health care systems are particularly vulnerable to corruption

Savedoff and Hussmann (2006)[1] detail how the high prevalence of uncertainty and asymmetry of information, as well as the number and variety of actors with diverging interests involved in the system, create opportunities for integrity violations in health. Uncertainty is inherent to the health sector, since individuals do not know whether or when they may become ill, or what disease or condition they may develop. Those who develop new treatments do not necessarily know which ones will succeed. Despite health providers’ best efforts, permanent risks remain inevitable to a certain extent. Such uncertainty creates the need for risk pooling through an insurance mechanism as part of the system so patients can bear the costs associated with future illness and needed care. But the underlying drivers of health care costs (including technology, but also the possibility of systemic risks such as a pandemic) are much more complex than in other lines of insurance business (e.g. automobile), making health insurance itself a risky endeavour. Apart from that, asymmetry of information characterises most transactions in the health sector. Patients, physicians, insurers (or payers in general) and industries that develop new technologies all possess certain information or expertise that is not Always available to others. Health professionals in particular have a double monopoly position with regard to information: towards their patients, who turn to them for advice but expect confidentiality; and towards managers, government and other actors that regulate and may finance their services (Freidson, 2001[2]). Finally, the sector is characterised by a high degree of fragmentation and decentralisation of responsibility among the various actors involved in the delivery of services, financing and regulation.

The combination of uncertainty, asymmetric information and fragmentation makes it difficult to standardise services, monitor behaviour and ensure transparency in the health care system. Many transactions in the health sector result from delegation of responsibilities from one actor to the following (e.g. from patient to physician, from payer to physician, from patient to the regulator, etc.). Economists label these situations “agency relationships”: a “principal” who has a direct stake in the result delegates a task to an “agent”. These relationships are often imperfect in the sense that agents can choose not to act in the best interests of the principal, attributing suboptimal results to uncertainty or information that the principal cannot verify. While economists primarily see this as a source of inefficiency, the situation paves the way for fraud, abuse and corruption.

Complications arise from the fact that value and quality are particularly difficult to define and measure in health. Prices are not as easily set in health as in sectors where supply and demand for a standardised and observable product of a given quality can be readily captured. In fact, many prices for health goods and services are negotiated, which generates opportunities to extract profits from the system to an extent that is contrary to the general interest.

Finally, the large amount of public money invested in the health sector probably contributes to opportunities for fraudulent behaviours. Indeed, on average in the OECD, 15% of government expenditures are allocated to health (OECD, 2015a[3]). National Health Accounts (NHA) data show that the share of government expenditures on health ranges from 10% to 22% (OECD, 2015b[4]).

The impact of corruption in health is not merely financial

The analysis presented here deliberately focuses on the financial impact of integrity violations in health, which can be direct (money is diverted from the system) and indirect (the risk of corruption requires additional investments in prevention or detection activities). But integrity violations — particularly in the health sector — have far-reaching consequences, direct and indirect, tangible and intangible, in both the short and long term. The 2013 European Commission study on fraud and corruption in the health sector pointed this out.

In particular, integrity violations can affect:

- The quality of goods and services provided in the sector. Poor quality can be detrimental to human health, either: i) directly through provision of substandard quality of medicines or equipment or of unnecessary service; or ii) indirectly if, for instance, corruption results in less than adequately qualified providers gaining access to the market. If such problems are frequent, it can even discourage or force honest brokers out of the market and undermine the service delivery system itself. Substandard quality can lead to costly adverse events (see Chapter 2 of this report) and lower health can undermine growth in the longer term.

- Access to care and equity. Corruption, for instance informal payments, can discourage access to care, likely affecting lower-income groups disproportionately.

- Allocative efficiency. On a systemic level, corruption can distort allocations within the health sector and between health and other sectors. OECD (2015c)[5] summarises evidence that more corrupt countries appear to spend less on health.

- Public trust and welfare. Access to health services is required by everyone. Widespread corruption in the sector can thus be very tangible to the population and undermine trust in public systems and society.

1.2. How much fraud, abuse and corruption really exists in the health sector?

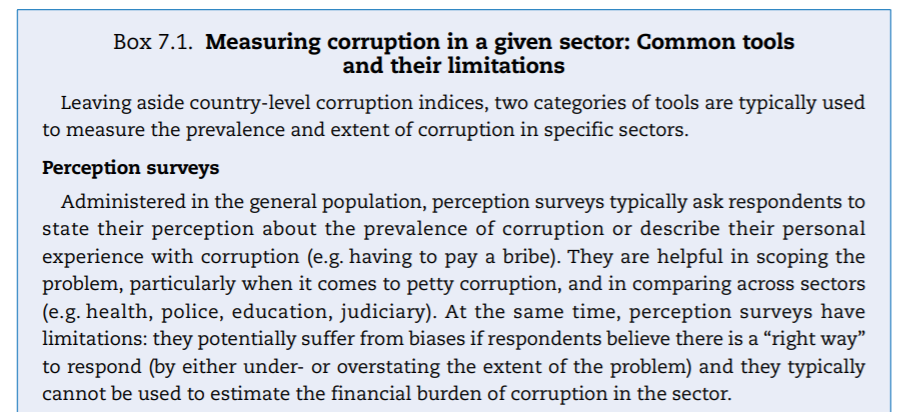

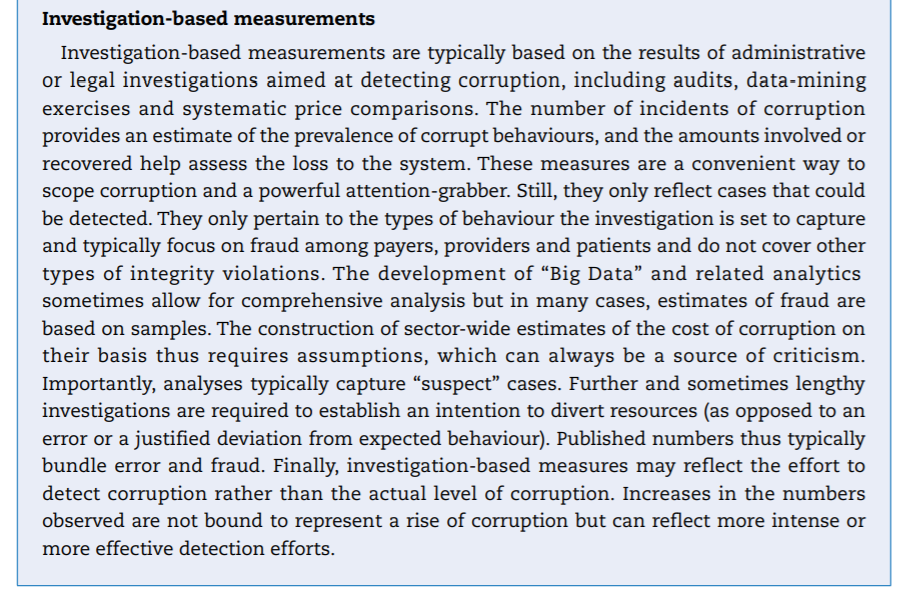

Integrity violations in health are notoriously difficult to measure. For one, the understanding of what may constitute fraud, abuse and corruption is not uniform. In addition, the manifestations of integrity violations are so polymorphous that they cannot be summarised in a simple metric or costed out systematically. Other measurement issues include whether the cost of activities aimed at preventing, deterring or fighting corruption should be included in a measure of their burden or whether estimates of negative externalities on health and other societal costs should be factored in. Above all, integrity violations, which are covert — if not criminal — activities by nature, do not lend themselves easily to measurement. In effect, no comprehensive attempt at measuring the impact of fraud, abuse and corruption in health could be identified in any of the OECD countries.[6] In this context, two types of tools are typically used to capture the importance and cost of integrity violations in the health sector: perception surveys and investigation-based measurements.

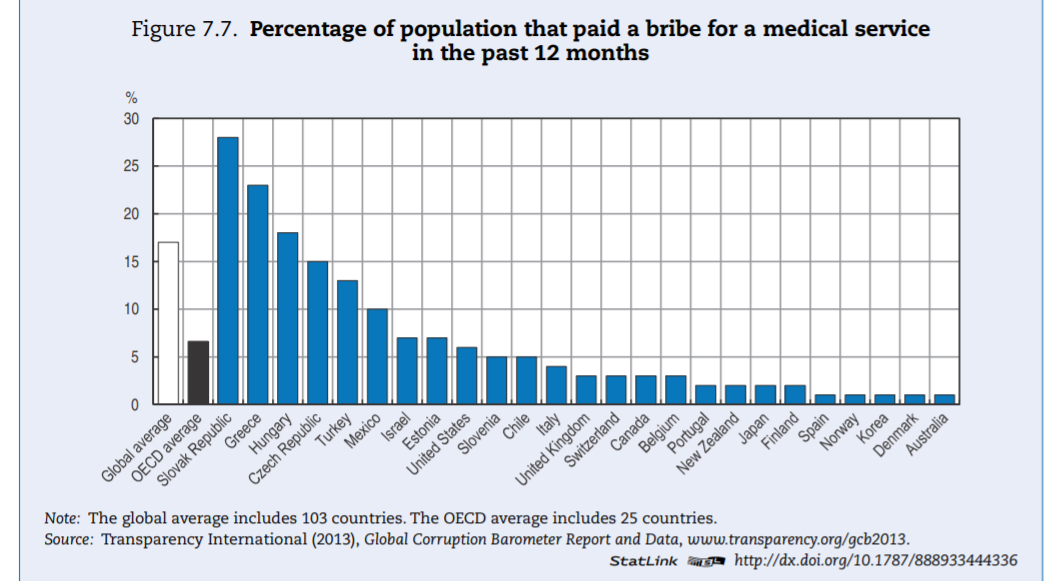

Perception surveys show that corruption prevails in the health sector

Perception surveys are one tool commonly used to assess the prevalence of corruption in various sectors (Box 7.1). They focus on eliciting citizens’ perceptions of and actual experience with corruption and bring to light the scope of the problem and its relative importance across sectors and countries. The 2013 Eurobarometer survey (European Commission, 2014[7]) and the 2013 Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer provide the most recent cross-country comparisons of the perceived level of corruption across a range of sectors, including health. Neither survey focused on OECD countries, but both included some of them, providing interesting insights and opportunities for cautious comparisons.[8]

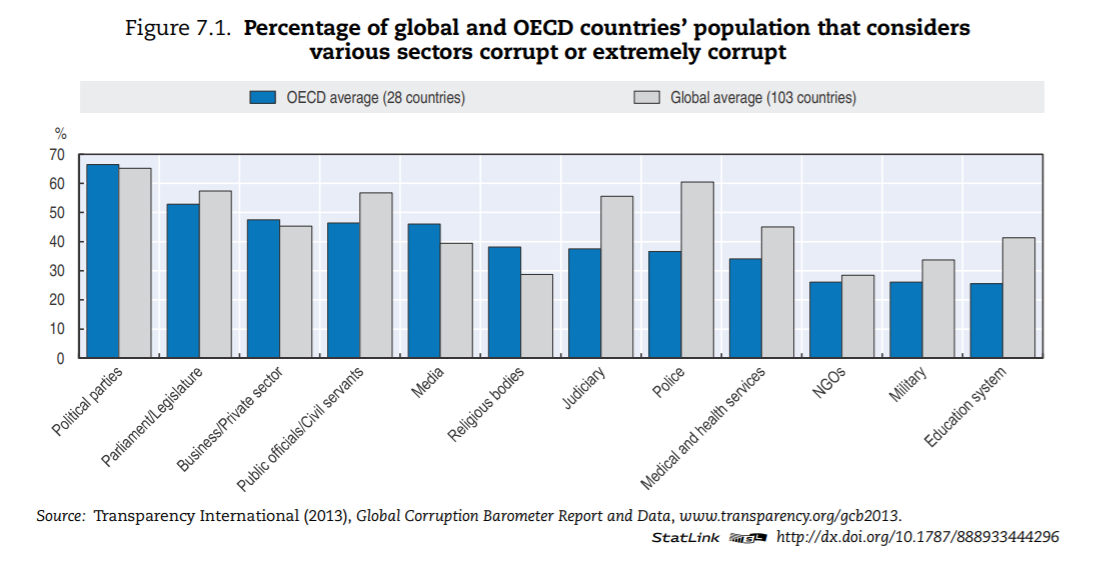

A comparison of OECD and global averages (Figure 7.1) suggests that corruption is less prevalent in OECD countries than globally, especially in the delivery of services that are typically publicly financed or delivered, such as police, judiciary, education and health care.

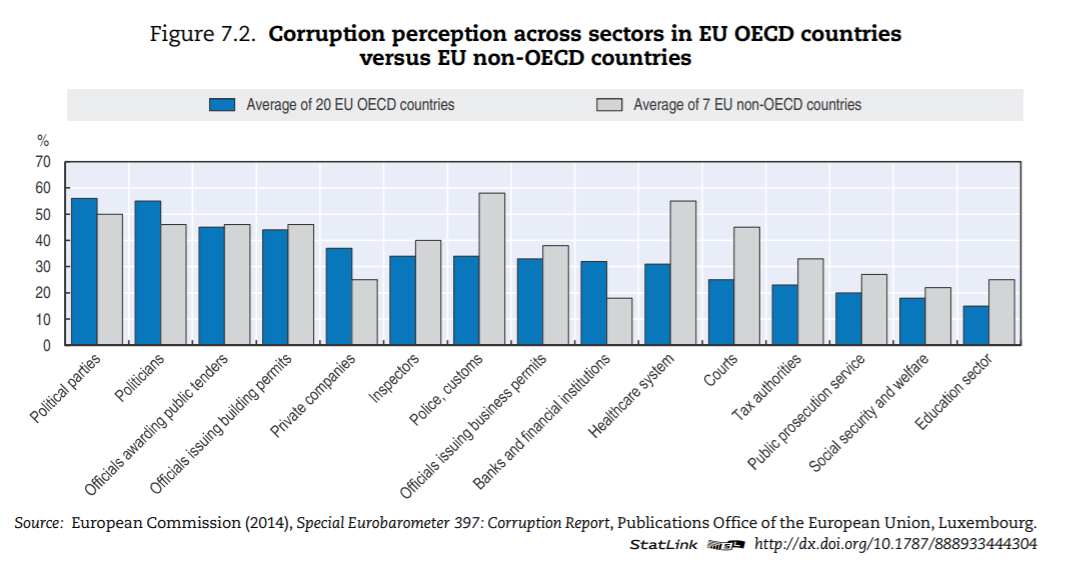

The health sector — in OECD countries — is ranked in the bottom third of corrupt institutions. Nevertheless, a third of respondents deem the sector as corrupt or extremely corrupt (versus 45% globally). In Europe, a similar pattern can be found (Figure 7.2). In the list of 12 institutions and sectors listed, health is in the bottom third for OECD countries. Still, around 35% of citizens in OECD European Union (EU) countries believe that “giving and taking of bribes and the abuse of power for personal gain is widespread” in health. The number is close to 55% in EU countries that are not part of the OECD.

Figure 7.1. Percentage of global and OECD countries’ population that considers various sectors corrupt or extremely corrupt

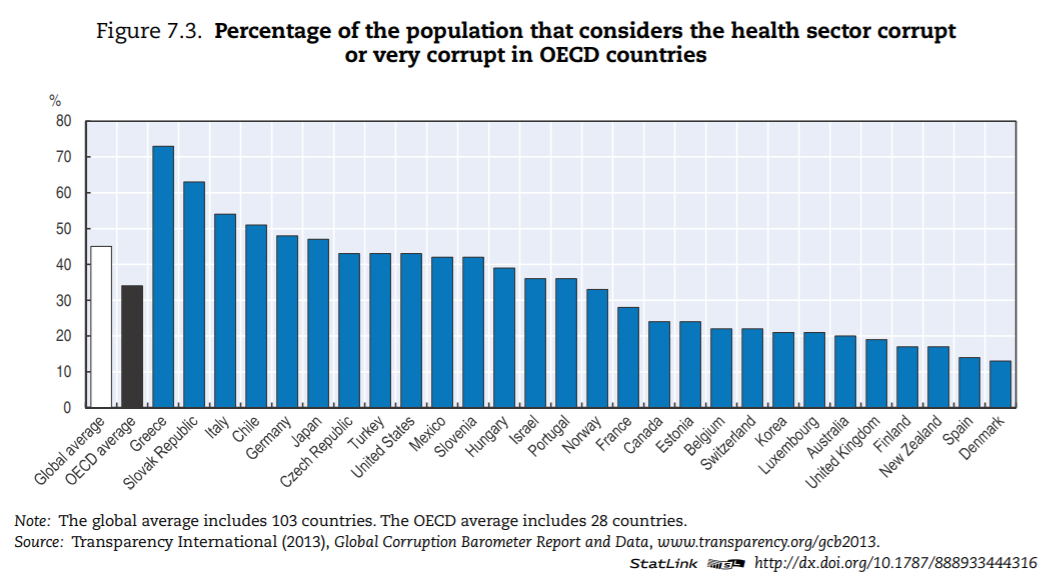

Levels of corruption seem highly variable across OECD countries. Figure 7.3 presents the percentage of the population that believes the health sector to be corrupt or very corrupt for all OECD countries present in the Transparency International database. The level of perceived corruption in health within OECD countries varies between 10% and 70%. Perceived corruption seems lower in many Commonwealth nations and Nordic countries of the OECD.

Investigation-based measures provide some insight into the cost of fraud in a number of countries

Investigation-based numbers are unlikely to provide a full picture of corruption. As previously highlighted, no reliable way exists to evaluate the overall cost of corruption, if only because of undetected offences (see Box 7.1). Further, if a wrongful transaction is suspected, the determination of whether it constitutes fraud or corruption is generally a lengthy exercise, sometimes only finalised in a court of law. Thus in many cases, published numbers refer to suspicious transactions (including errors). Building sector-level estimates usually requires formulating assumptions, for instance to extrapolate sample data, and may be informed by expert opinion.

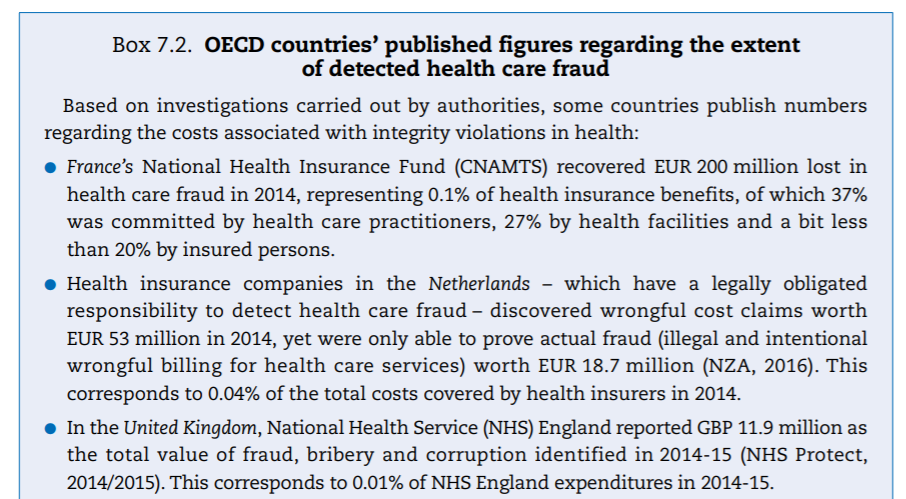

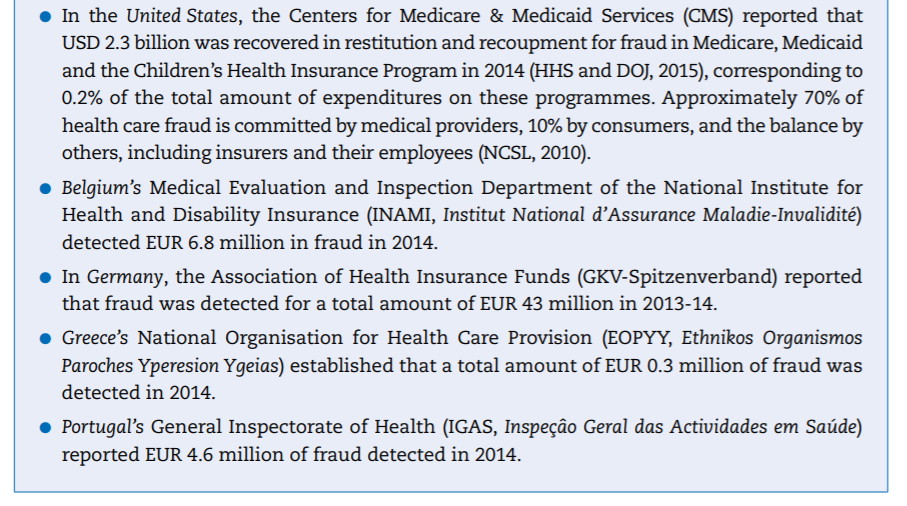

Investigation-based numbers published by authorities are typically small, but the return on investment to detect and combat fraud can still be high. A number of institutions regularly publish figures on the extent of fraud detected, based on investigations carried out by authorities. Some examples are displayed in Box 7.2. In instances where it is possible to relate the amounts of fraud detected to the expenditure on the programmes where the investigation took place, the ratios are low: the amounts of fraudulent payment typically represent less than half a percentage point of programme expenditure. This does not mean that the return on investment in fraud detection is negligible.To give an idea, the return on investment of a US detection programme for 2013–15 was estimated at USD 6.1 returned for every USD 1.0 expended (HHS and DOJ 2016[12]). Beyond this, experts believe that having an active programme in place acts as a deterrent in and of itself, helping to reduce the amount of fraud.

Often, however, estimates and investigation-based numbers vary by an order of magnitude, as illustrated by two examples:

- In 2014, USD 2.3 billion was recovered in restitution and recoupment for fraud by Medicare and Medicaid (HHS and DOJ, 2015[13]), representing 0.2% of expenditure on the programme that year. Berwick and Hackbarth (2012)[14] estimated that the cost of fraud to these programmes would be at least USD 30 billion, and maybe as high as USD 98 billion. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) in fact concluded that no reliable baseline estimate of the amount of health care fraud currently exists in the United States (CBO, 2014[15]).

- In the Netherlands, Hasaart (2011)[16] showed that adverse behavioural responses (e.g. overbilling for care) of medical specialists and hospitals linked to the hospital payment system alone could amount up to EUR 1 billion (about 6% of total hospital care and medical specialist care expenditures for the year the estimate was produced). The payment system was subsequently revised in a way that could have reduced the amount but the number is still in sharp contrast to the EUR 18.7 million recovered by all health insurance funds in 2013.

- In the United Kingdom, National Health Service (NHS) England reported GBP 11.9 million as the total value of fraud, bribery and corruption identified in 2014–15 (NHS Protect, 2014/2015[18]). This corresponds to 0.01% of NHS England expenditures in 2014–15.

- In the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reported that USD 2.3 billionwas recovered in restitution and recoupment for fraud in Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program in 2014 (HHS and DOJ, 2015[19]), corresponding to 0.2% of the total amount of expenditures on these programmes. Approximately 70% of health care fraud is committed by medical providers, 10% by consumers, and the balance by others, including insurers and their employees (NCSL, 2010[20]).

- Belgium’s Medical Evaluation and Inspection Department of the National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (INAMI, Institut National d’Assurance Maladie-Invalidité) detected EUR 6.8 million in fraud in 2014.

- In Germany, the Association of Health Insurance Funds (GKV-Spitzenverband) reported that fraud was detected for a total amount of EUR 43 million in 2013–14.

- Greece’s National Organisation for Health Care Provision (EOPYY, Ethnikos Organismos Paroches Yperesion Ygeias) established that a total amount of EUR 0.3 million of fraud was detected in 2014.

- Portugal’s General Inspectorate of Health (IGAS, Inspeçâo Geral das Actividades em Saúde) reported EUR 4.6 million of fraud detected in 2014.

Every year, PKF, an accounting firm, and the Centre for Counter Fraud Studies (CCFS) at the University of Portsmouth jointly publish an assessment of the cost of health care fraud, based on data from 33 organisations in 7 OECD countries (Australia, Belgium, France, New Zealand, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States). They reportedly only include statistically significant and methodologically sound measurement exercises subjected to external validation. The latest report (Gee and Button, 2015[21]) shows that the loss to fraud and error is an average 6% of related health expenditure. In the majority of cases, this loss ratio lies between 3% and 8%, and in nearly 90% of cases fraud and error represent more than 3% of the expenditure reviewed. Given the recovery ratios available (Box 7.2), it is fair to assume that measures against integrity violations in health within OECD countries could be strengthened.

1.3. Resource-diverting “integrity violations” can be grouped in three broad categories

From a policy perspective, integrity violations in the health sector are best divided into three categories depending on who is involved and the type of “transactions” affected.

Going beyond labels captures a wide range of dishonest behaviours

Deliberately putting aside semantic discussions, this study pragmatically sets out to include all integrity violations that engender private benefit at the expense of the health care system. Corruption, fraud, abuse, regulatory capture, revolving door politics, embezzlement, collusion and nepotism are among the many terms defined by Transparency International’s plain language guide on corruption (Transparency International, 2009[22]). These definitions typically describe various facets of the integrity violation itself, for instance whether it includes one or more people (fraud versus corruption), whether a rule is broken or not (abuse versus fraud), or the degree of pressure exerted (from influence to extortion). All of these terms correspond to problems that can take place in the health sector. From a policy perspective, characterising and distinguishing each and every term precisely is not particularly relevant. The present study thus uses “integrity violations” as an umbrella term to capture them all. Integrity violations include the entire spectrum of behaviours that reasonable and well-informed laypersons observing the health care system would — in all likelihood and in most health care systems — consider inappropriate and unethical. The integrity violations included in this analysis further have in common that they increase the costs of goods and activities in the health sector and divert resources from their intended purpose to dishonestly serve the interest of specific individuals or groups.

Integrity violations considered here thus include what most practitioners label corruption: “the abuse of public or private office for personal gain” (OECD, 2008[23]). This commonly used definition already covers a large set of possible integrity violations and hints: i) that corruption may involve a wide diversity of actors, from public officials to individual private medical practitioners; and ii) that the “gain” is not necessarily immediate and monetary but may be intangible and delayed. Indeed, personal gain can come in the form of gifts, honorary titles or recognition, sponsorship (of training, research, events) or future paid or unpaid services (consultancy contracts, jobs, other favours that can be called in). This definition does not explicitly include situations where the dishonest behaviour serves — directly or indirectly — the interest of groups of stakeholders (such as an industry or a profession).[24] Although it is hard to draw the line between, for instance, lobbying and undue influence on regulation or between strategic marketing and abusive promotion of commercial interests, these questions are certainly relevant in the health sector.

Fraud and abuse are included in the scope of this study. Corruption is generally understood to involve more than one participant, one of whom at least is in a position to abuse his position. Fraud and abuse, in contrast, are more individual in nature. Fraud is generally defined as knowingly and wilfully executing, or attempting to execute, a scheme or artifice to defraud the health care system (adapted from the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act).[25] In that respect, fraud differs from errors, which are unintentional. Anyone in the health care system can commit a fraud, including a patient. From a legal perspective, abuse mostly differs from fraud in that a rule has to be broken for misbehaviour to be labelled fraud. If an investigator cannot establish the act was committed knowingly, wilfully and intentionally, it is perceived as an error (Rudman et al., 2009[26]). From an operational perspective, however, if the objective is to reduce waste, then fraud and abuse are equally important. Detecting and correcting errors is more an administrative task in nature but it can make sense to functionally integrate fraud and error detection. In any case, all forms of integrity violations ultimately lead to waste — even if the cost is not necessarily direct, immediate or even measurable.

In conclusion, it is important to recognise that the boundaries of what constitutes integrity violations cannot be universally defined. Indeed the question of whether a given act should be considered corrupt may find a different response depending on a country’s cultural fabric. For instance, giving or accepting a present in the context of a patient-physician relationship may be considered normal in one culture and unacceptable in another (Blind, 2011[27]).[28] Consequently, no consensus exists among countries about which integrity violations should be considered offences in the eyes of the law, although ratification of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention (which covers the bribery of foreign public officials) by OECD countries in 1997 constituted a first step towards recognition of a common range of potential offenses related to corruption.

For policy purposes, integrity violations are best grouped in three categories

From a policy perspective, grouping integrity violations according to who is involved in the related transactions is proving to be most helpful. Savedoff and Hussmann (2006)[29] first used a stylised representation of the main actors involved in the health care system to illustrate the many ways in which corruption could manifest.[30] In the same spirit, five categories of stakeholders that can perpetrate or be victims of integrity violations are distinguished here:

1. Providers of medical goods and services. This category includes individual service providers (physicians, nurses and other health professionals), health facilities and retail pharmacies.

2. Suppliers or manufacturers of medical goods and services used in the process of delivering care. These include the manufacturers of goods and services as well as wholesalers that provide pharmaceuticals, medical devices and medical equipment as well as — for instance — health ICT applications.[31]

3. Payer(s). These are entities that pool funds in the health care system and finance care on behalf of all or part of the population. Depending on the country, payers can be public entities or private insurers, single or multiple.

4. The regulator of the sector. The regulator represents the government through its ministry and often a number of dedicated agencies as well as the individuals who work for them.

5. Individuals. Patients, taxpayers or the insured can either commit or be the victim of fraud.

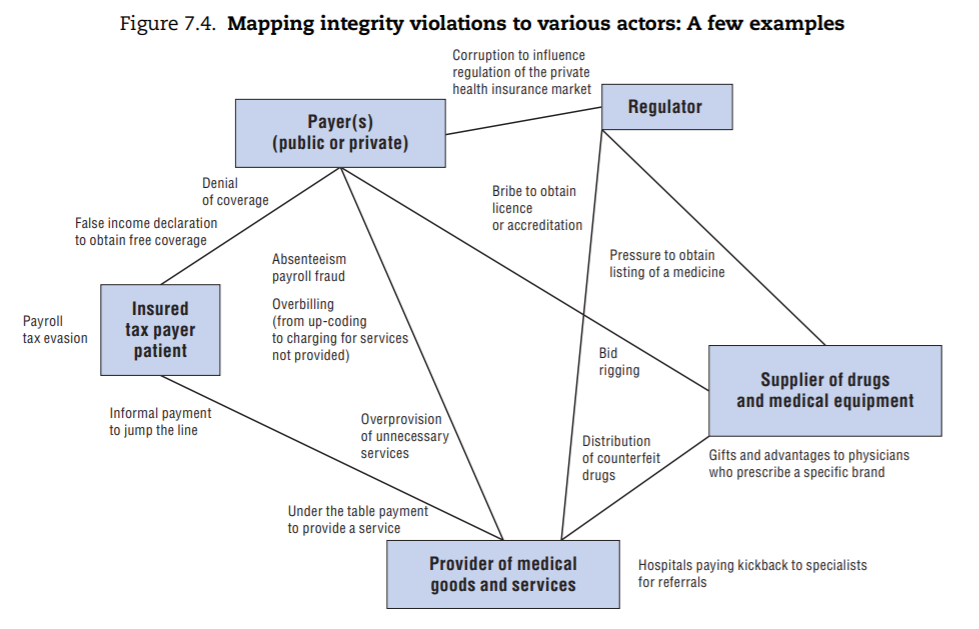

A few specific examples of integrity violations are mapped to these types of actors in Figure 7.4 for illustrative purposes. These were drawn from examples of corruption described in the literature on fraud abuse and corruption in the health sector and mapped to the stakeholders involved.

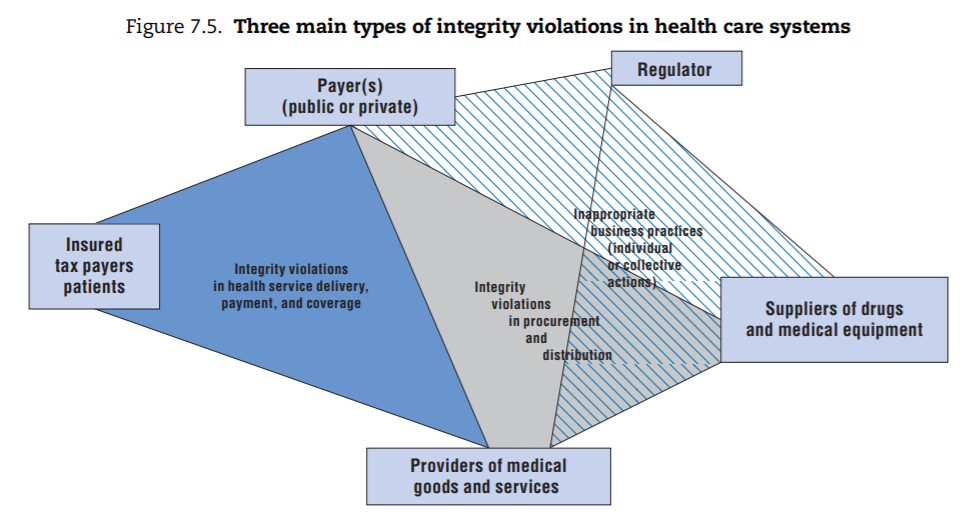

From this exercise, three main categories of integrity violations emerge (depicted in Figure 7.5):

- The first category takes place in the context of transactions involving providers of health services, payers of these services, and/or individuals. Depending on the specific situation, each can be perpetrator or victim. These integrity violations are sometimes grouped under the label “health care fraud”, particularly in systems where competitive health insurance dominates, but variations of these integrity violations can be found in all health care systems.[32]

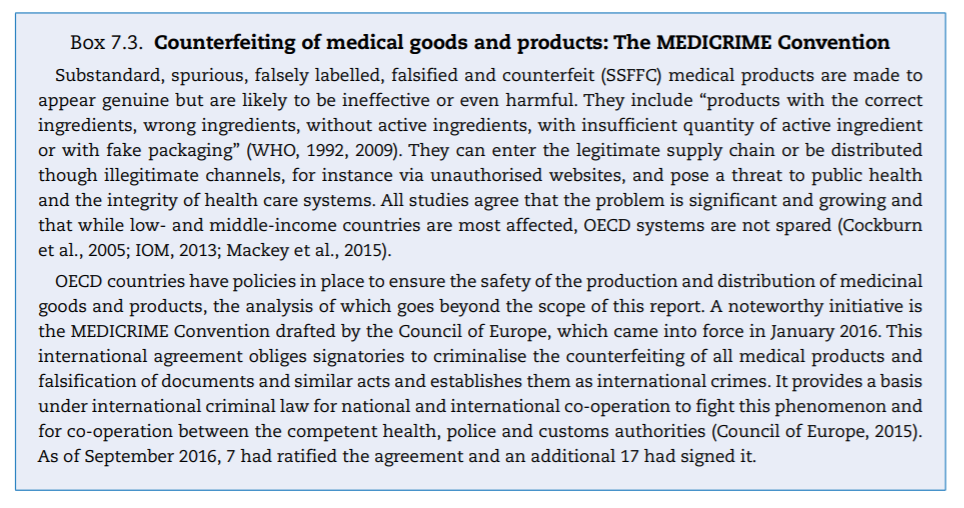

- The second category primarily involves suppliers of drugs and medical equipment as perpetrators; (financial) victims are the purchasers of these goods or services, most of which are typically payers or providers themselves (e.g. hospitals). These integrity violations take place in the context of procurement, which includes purchase as well as distribution of drugs and equipment. In the health sector, delivery of substandard or counterfeit drugs or medical devices is of particular concern given the potential safety implications (Box 7.3).

- The third category covers a range of inappropriate business practices that ultimately serve to secure more favourable market positions either for individual stakeholders or for their “trade/industry”. These integrity violations can be perpetrated by any stakeholder for whom the health sector is a source of revenue. This category includes what is sometimes called “systemic corruption”, where representatives of an industry (pharmaceutical companies, private insurers or provider lobbies) exert undue influence on the regulator at the system level. It also covers situations where any of these stakeholders commit fraud, abuse or corruption in their own limited interest (e.g. to gain market entry for a specific product, to obtain a licence to operate, or to ensure their product is favoured over a competing one). In all these cases, the “victim” of the fraud is generally the regulator and the cost is ultimately borne by the public payer(s).

The remainder of this chapter reviews some of these categories in more detail to learn what health sector policy makers are doing to tackle them in OECD countries. This focus has a number of implications for the scope of the work, as follows:

- Countrywide challenges in public governance are not discussed. As public funding dominates health in most OECD countries and the sector is heavily regulated, the overall quality of governance (particularly in domains such as public finance and budgeting, public financial management, public procurement and civil service management) frames what happens in the health sector. An overall poor level of governance in a given country is likely to permeate the health sector. Conversely, if the civil service or public procurement is corrupt, the health sector is unlikely to be able to address the problem through sector-specific measures alone. Consequently, for instance, issues related to tackling absenteeism in public health facilities or corruption in public procurement in health specifically are not covered as they would necessitate research beyond the scope of this report.[39]

- Another assumption made is that basic checks and balances and fairly solid administrative systems are in place. In other words, in the context of OECD countries, it does not make sense to discuss them in detail.

- With this in mind, the report focuses on two domains where at least some OECD countries have introduced sector-specific interventions to tackle integrity violations: service delivery and financing and inappropriate business practices.

To map, describe and classify integrity violations and policy measures aimed at tackling them, data were retrieved from responses to a survey undertaken for this report. In addition, an extensive review of literature was carried out, covering studies, reports, journal articles and other documents that discuss integrity violations in health.

2. Variable levels of effort by OECD countries to tackle integrity violations in service delivery and financing

The majority of studies on integrity violations in health care focus on the primary process of health care service delivery and financing. Different types of integrity violations related to this primary process are reviewed and the main categories prevalent in OECD countries tentatively identified. Based on this, the rest of the section highlights the variety of institutional set-ups chosen by countries to deal with these integrity violations and the common features of the strategies used, with a focus on the experience of those who responded to the questionnaire.

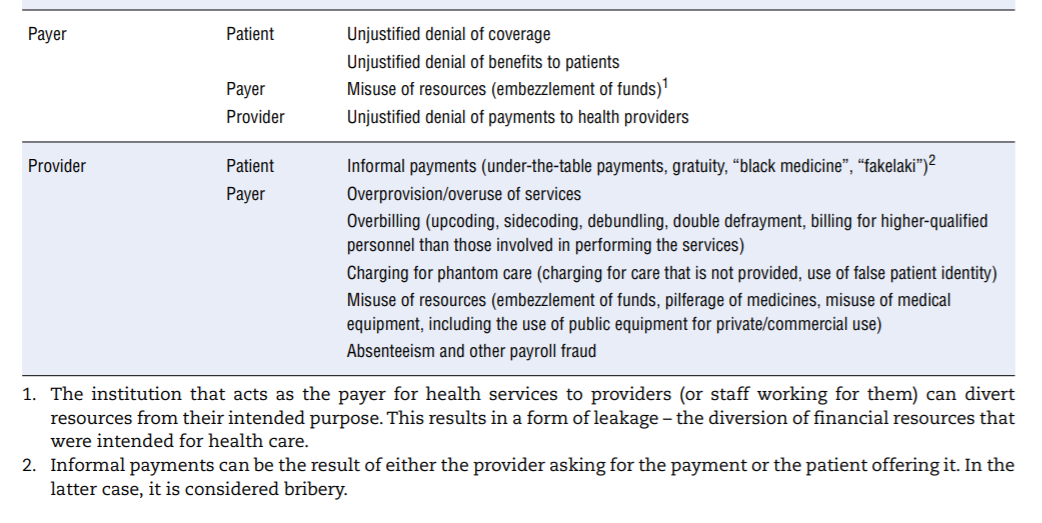

2.1. Integrity violations in service delivery and financing are varied and most often originate from providers

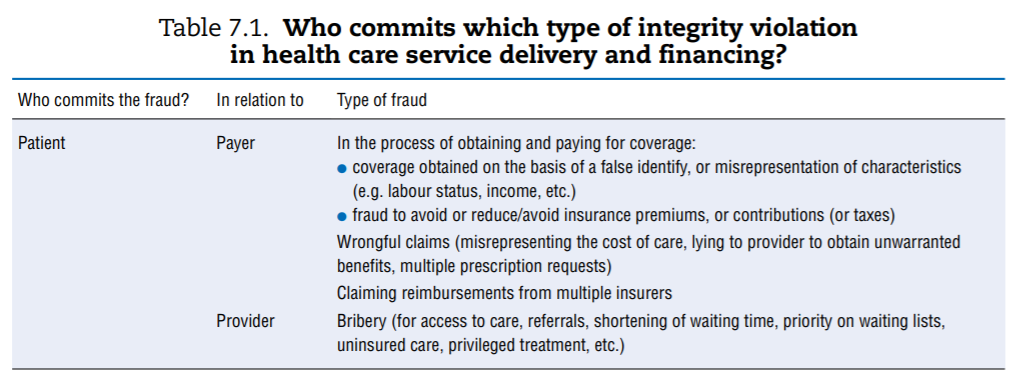

An extensive review of mainly academic and grey literature identified the various manifestations of integrity violations involving providers, patients and payers. Table 7.1 organises the findings by linking perpetrator (first column) and target (second column). In reality, collusion can take place between those involved in perpetrating integrity violations (for example, both patient and provider can seek to defraud the payer). The table abstracts from system-specific examples but seeks to provide a comprehensive overview.

The table calls for a few remarks:

- It illustrates the point made in the first section regarding the vast range of opportunities for corrupt behaviour in the health sector given the number and diversity of actors and transactions between them. Behind each example above lie specific cases documented in a number of country-specific contexts.

- Not all types of integrity violations described are relevant to all OECD countries, simply due to the various ways in which countries’ systems are organised and financed. For example, if access to medical services is not based on a formal insurance mechanism or if insurance coverage is universal, patients have no interest in identity theft to obtain coverage. Similarly, absenteeism or payroll fraud is less of a concern in systems that rely on fee-for-service (FFS) payment than in systems with salaried providers (see also European Commission (2013)[40], which maps how different types are linked to diferente financing schemes).

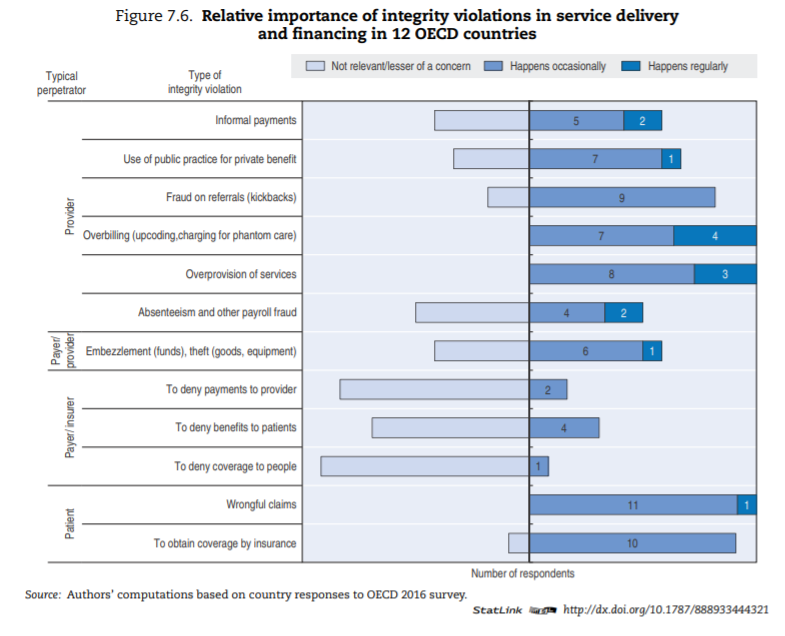

A significant proportion of the literature about manifestations of integrity violations in service delivery and financing discusses low-income countries; the question is open as to whether their content applies to OECD countries. To assess which types of integrity violation are most relevant, countries were asked to state their opinion on the relative frequency of specific types of integrity violations in service delivery and financing. Figure 7.6 provides an overview of the results for the 12 countries that responded.[41]

The sample is small, and reflects survey respondents’ perceptions, but results suggest that:

- Insurers/payers themselves are less likely to commit fraud towards patients and providers than the reverse. In most sample countries, this is deemed of little or no concern. Patients, on the other hand, appear to cheat the system occasionally everywhere. Providers are the most likely of the three to commit fraud and abuse regularly (this is aligned with the numbers observed in France and the United States, per Box 7.2).

- Overbilling — including upcoding, debundling and charging for phantom care — and overprovision of services (providing more care than necessary) are clearly the most widespread methods providers use to cheat the system.

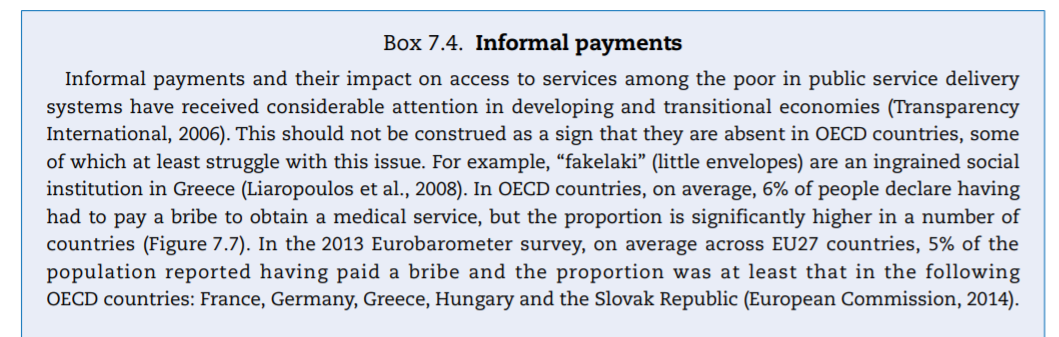

- Informal payments are of concern in more than a few OECD countries, contrary to intuition perhaps (see Box 7.4 for additional data).

- Absenteeism and embezzlement are relevant in some countries but seldom encountered in others.

Whether or not informal payments — consisting of either money or other valuable goods — are regarded as an integrity violation partially depends on culturally defined norms and habits of each country. In that regard, debates arise about the perfectly legitimate act of gift-giving versus the illegal transaction of bribery (Kurer, 2005[46]).

2.2. Various types of institutions tackle integrity violations in service delivery and financing

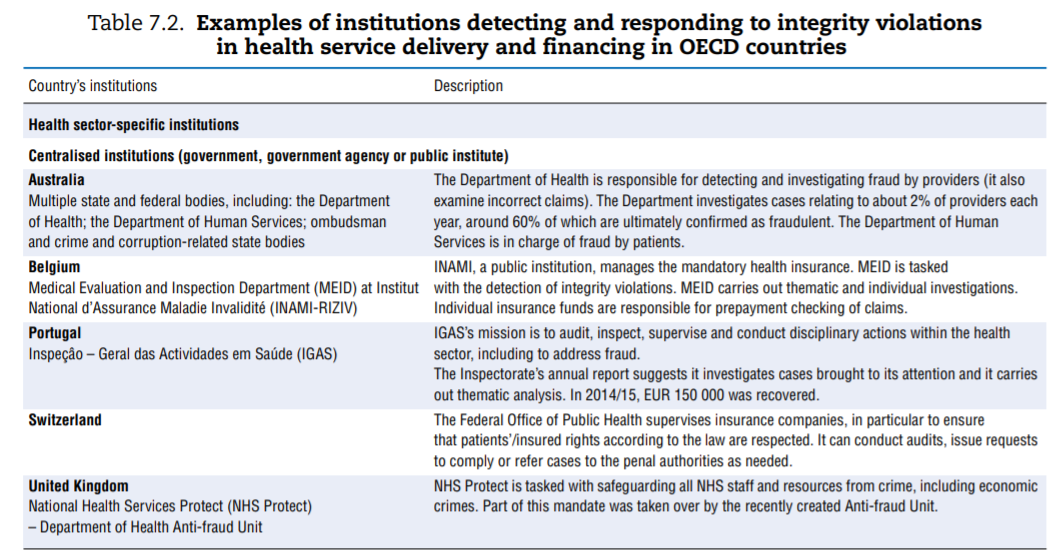

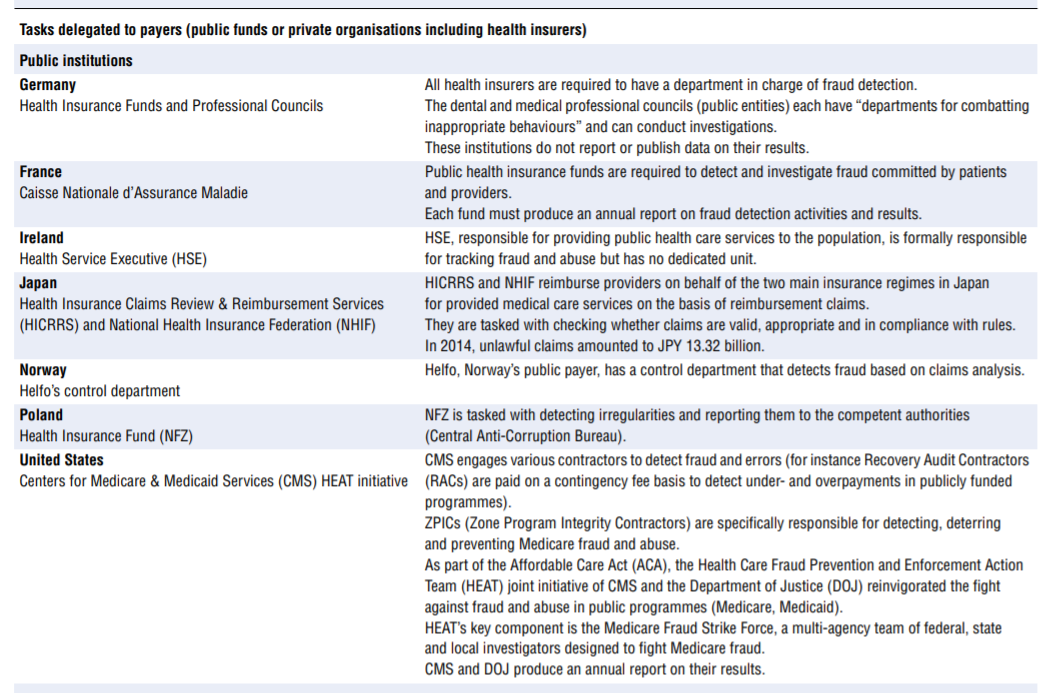

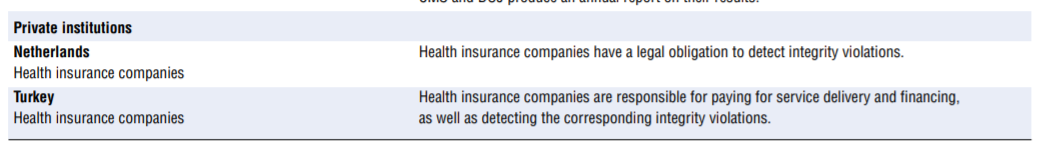

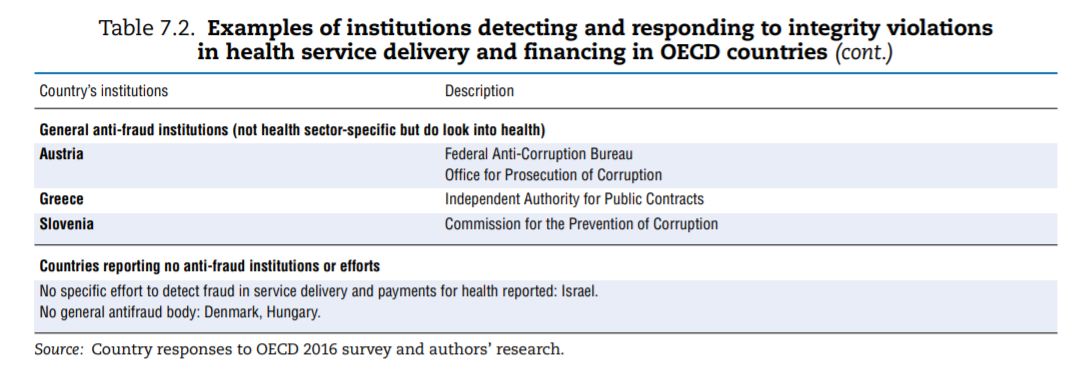

Efforts made to tackle integrity violations in service delivery and financing vary greatly across OECD countries. Some countries have dedicated institutions or organisations in place tasked to prevent or tackle integrity violations in health service delivery and financing. Others rely on more ad hoc approaches. Based on the survey results, augmented by analysis of grey literature and experts’ input, Table 7.2 describes various countries’ approaches.

Among the more than 20 countries for which the information was availed, countries’ institutional set-ups and strategies for dealing with integrity violations in service delivery and financing differ widely.

Some countries clearly put more emphasis on the issue than others. Four approaches were identified:

- A number of countries have dedicated departments in a central-level institution — e.g. a ministry (Australia, Belgium, Portugal and the United Kingdom), with some countries further splitting responsibilities depending on who perpetrated the fraud (e.g. frauds committed by patients versus providers are managed by two different entities in Australia).

- Nine countries explicitly delegate the responsibility to detect and address fraud and abuse to payers — public and private. Interestingly, in Germany part of the responsibility for detecting fraud and abuse perpetrated by providers lies with professional councils.

- In some countries, fraud in service delivery and payment falls under the general purview of a specific anti-corruption agency that can and typically does investigate health sector issues.

- Some countries appear to have neither health-specific nor general anti-corruption bodies in place. Some approaches and insights shared by countries regarding the set-up for fraud detection are worth highlighting:

- Actively detecting and combating fraud and corruption is not necessarily in health care payers’ direct interest. Ultimately, the payer is a financial intermediary between patients/clients (who may contribute to financing the system through taxes or premiums) and providers (with which payers have some form of contractual relationship). As such, payers typically have explicit fiduciary responsibilities. Still, fraud detection activities are costly and can be perceived as adversarial by both patients and providers. The benefits, on the other hand, are not necessarily direct. The cost-benefit ratio of fraud detection may not be perceived as high enough, and the “spontaneous” level of effort may be suboptimal. This might explain why in the Netherlands, private health insurance companies (which compete with each other) have a legal obligation to detect integrity violations. Germany also mandates that public health insurance funds have a dedicated department and report fraud to the judicial authorities. In contrast, in Switzerland, it is assumed that private insurers have an inherent incentive to combat fraud.

- The US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) systematically uses (separate) contactors to detect fraud and errors. Among contractors tasked with detecting errors, Recovery Audit Contractors, whose mission is to deal with improper payments, are incentivised by a contingency fee (a controversial programme). The CMS also contracts Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs) specifically tasked with detecting (via data analysis, hotlines, or based on reports of other contractors) and investigating instances of fraud.

- Some, but not all, institutions tasked with detecting integrity violations can enforce administrative sanctions. For instance in Belgium, the National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (INAMI, Institut National d’Assurance Maladie-Invalidité) has additional administrative judicial capacities, in the form of administrative courts within the national institution, that can impose administrative fines up to 200% of the amount involved in the integrity violation concerned. Australia can apply administrative penalties (which may be lowered when healthcare providers voluntarily admit wrongdoing), as well as professional sanctions or penalties when the activities are clinically inappropriate.

- Some countries choose to publish data on the results of their efforts at regular intervals (Belgium, France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States). In these countries, publication of results creates awareness of counter-fraud activities and is seen as a deterrent of further integrity violations.

- Countries recognise the value of sharing experiences in combatting integrity violations across public and private institutions as well as internationally. In the United States, the National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association created in 1985 comprises nearly 90 private health insurers and those public sector law enforcement and regulatory agencies that have jurisdiction over health care fraud. Some OECD countries are members of the European Healthcare Fraud and Corruption Network (EHFCN)[48] and the Global Health Care Anti-Fraud Network (GHCAFN), which includes Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States.

2.3. Effective detection of integrity violations in service delivery and financing requires data mining and review campaigns; responses must be well graded and credibly enforced

Approaches to detecting fraud and abuse in service delivery and financing can be more or less pro-active. Traditional approaches rely on the investigation of complaints or regular audits and controls. Some, but not all, countries set up tip-off hotlines (e.g. Australia, the United States) to encourage reporting of fraudulent behaviours. The United States developed several toolkits, training opportunities and materials for beneficiaries and providers to identify and reduce fraud. Statistical and data-mining tools are now an integral part of the fraud detection arsenal of many but not all countries.[49] Essentially, data mining can be used to: i) identify patterns[50] and deviations from them; and ii) screen cases that need to be further scrutinised for fraud and abuse. Various types of analysis can be deployed. Ranging from least to most complex:

- Rules-based approaches are the most simple and help identify cases that do not meet specific pre-set criteria. These controls are often automated and carried out prior to settling claims, for instance to verify that all the required information is available, that no major inconsistencies exist, and that the claim complies with formal rules and guidelines (e.g. the provider is duly registered, the number of sessions prescribed does not exceed the allowed limit, etc.).

- Outlier or anomaly detection techniques focus on identifying usual patterns (for instance, typical treatment patterns by diseases), and deviations from them. These methods can lead to identification of geographic variations in medical practices (see Chapter 2).

- Predictive techniques use information about past fraud to flag high-risk fraud candidates. Social network analyses identify patterns of transactions between different entities across time and can help identify collusion between perpetrators and networks organised to defraud the system.

In addition to, or as a result of, the detection of specific instances of fraud, agencies typically carry out programmed thematic investigations targeting specific issues. For instance, in 2014, the Belgian INAMI investigated repetition of restorative dental care; France’s CNAMTS (Caisse Nationale de l’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés) investigated home-based hospital care to determine whether services supposed to be included in a lump-sum payment were not also charged on an FFS basis; England’s NHS Detect focused on payroll fraud; and Portugal focused on cochlear implants.

To address suspicious patterns that could result from integrity violations, practitioners highlight the importance of a stepwise, graded, comprehensive and credibly enforceable response. This response should — as relevant — incorporate measures to prevent future occurrences of similar problems and engage the community of providers in a constructive dialogue. This is the case when the pattern falls into the category of “abuse” rather than fraud; in other words, when no pre-existing rules are explicitly broken (for instance, overprescription of specific tests, unusual frequency of repeated visits, etc.). In these situations, especially if many providers behave similarly, the nature of the problem does not differ fundamentally from that of the “overtreatment” examined in Chapter 2.

Engaging professional organisations or scientific societies can help generate technical consensus around the fact that certain behaviours are — under most circumstances — inappropriate. Based on this, new and acceptable rules or guidelines can be created. Subsequently, this reduces opportunities to abuse the system and more clearly redefines future outliers as fraudulent. Communication and other soft tools can be used to limit future offences. Sending targeted information, benchmarking data or warnings to all providers or the subset of individuals whose behaviour is unusual can effectively deter future offences (because perpetrators know the behaviour is under observation or because they feel peer pressure). Still, entities involved in detecting fraud and abuse recognise the difficulty they face in building a constructive dialogue with health professionals who are typically — and unsurprisingly — reluctant to engage in a dialogue on fraud and abuse, which they expect to reflect badly on their profession. Putting more emphasis on erros and good practice can be more constructive.

Deeper investigation of specific cases and outliers is warranted. As soon as the investigation process starts though, efforts must go into engaging and communicating with perpetrators (typically health professionals), recognising that errors can happen and that special circumstances can dictate deviations from good practice. As relevant, suspects can be offered the option to correct their “mistakes” and voluntarily repay the amounts due. Investigations often start with formal or material checks and requests for additional information from the parties involved. More rarely, full-scale investigations require forensic techniques and involve inspectors. Because of privacy considerations and doctor-patient confidentiality, inspectors may need to be specifically trained physicians. They can reach out to all parties involved, for instance patients, to verify their circumstances or the care that they received (ZN, 2011[51]).

The last step is to take — as feasible — administrative and disciplinary sanctions and/or initiate civil or criminal legal proceedings. The Unites States recently expanded the scope or magnitude of sentences and penalties for integrity violations in health service delivery and financing.[52] In addition, the United States and the Netherlands enhanced funding for the prevention and detection of fraud, abuse and corruption in health care. Countries with active programmes (e.g. Belgium, the Netherlands and the United States) highlight the importance of organising and even formalising co-operation between health and judicial authorities. In 2009, the United States created a joint task force for combatting fraud on Medicare between the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) that is a multi-agency team of federal, states and local investigators.

Integrity violations in service delivery and financing are not rare. Yet large cross-country variation arises in the attention and resources dedicated to the problem. Countries that have stronger institutions and apply more systematic efforts always seem to succeed in detecting significant amounts of fraud. In the end, the amounts recovered remain fairly small compared with total health expenditure. Still, these programmes likely have positive externalities and deter at least some individuals who could be tempted to cheat the system. In recent years, some countries, including France, the Netherlands and the United States, stepped up efforts to combat integrity violations in service delivery and financing. As part of the waste agenda, more countries could consider joining them.

3. Inappropriate business practices: Opening the governance debate

The second category of integrity violations reviewed in this chapter, inappropriate business practices, can potentially be perpetrated by anyone who derives income from selling goods and services in the health sector. This includes individual health care providers, health facilities and a number of industries, notably in the domains of insurance, pharmaceuticals and medical devices. All of these stakeholders are legitimately involved in the health care system and the vast majority conduct their business in entirely appropriate ways. Yet on any day, a story can emerge about an unqualified person delivering services,[53] a hospital group giving a range of inducements to a consultant practice in exchange for referrals (Godlee, 2015[54]), or a pharmaceutical company using unethical marketing practices. Compared with integrity violations in service delivery and financing or procurement, these inappropriate behaviours are less directly linked to the actual process of care and perhaps even less observable. They ultimately target the regulator, understood here as the institutions entrusted with safeguarding the public’s interest and safety.

The review of the literature on and actual cases of fraud and corruption in health care systems show that at least some of these inappropriate business practices occur in most OECD countries. The 2013 European Commission report collected 86 examples of corruption occurrences across EU countries, many of which could be categorised as “inappropriate business practice”. More recently, the first report of the newly established chapter of Transparency International on Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare Programme covers inappropriate practices in research and development, marketing and registration in the pharmaceutical industry and offers additional examples of inappropriate practices in OECD countries (Transparency International-UK, 2016[55]).

This final section presents a simple framework that captures the various inappropriate business practices mentioned in the documents reviewed and identifies some of the regulatory approaches countries chose to deal with them. The research undertaken for this report and the responses received to the questionnaire highlight that inappropriate business practices are of increasing concern to OECD countries. At the same time, the case for linking this discussion to the waste agenda is perhaps weaker. The issues at stake are equally important, though: patient safety and the transparency, integrity and accountability of decision making in the health sector. Rather than being comprehensive, the following discussion paves the way for future discussion.

3.1. The pursuit of legitimate business objectives can give rise to inappropriate business practices

The first difficulty lies in identifying what constitutes inappropriate behaviour. If a rule is broken, the case is straightforward: for instance, an entity forges credentials to enter a regulated market. But as previously highlighted, the line between appropriate and inappropriate is drawn at different points in different cultural and policy contexts. In fact, the definition of the term “institutional corruption” highlights that an entity operating in a “legal or even currently ethical way” can still be “corrupt” if its institutional environment was designed under a systematic and strategic influence that weakens its ability to achieve its societal mission (Lessig, 2013[56]). In health, a concern is that some groups of stakeholders (the pharmaceutical industry, the medical lobby, the insurance industry) have the means to — and do — exert such influence. Following the literature, the mapping of inappropriate business practices therefore includes: i) instances when stakeholders act inappropriately to promote their individual business (individual strategy); and ii) situations where the organised action of groups of stakeholders undermines achievement of health care systems’ goals (collective strategy[57]).

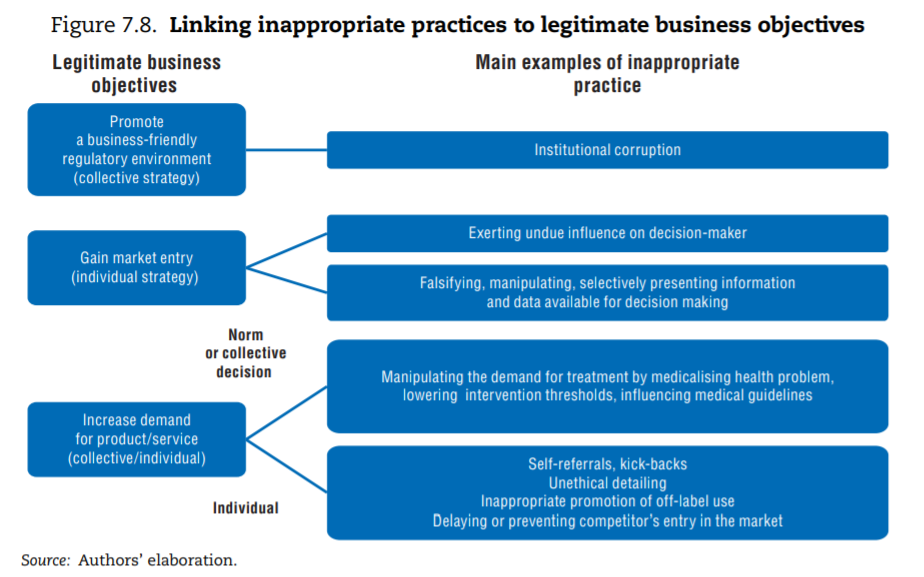

The framework below links the various inappropriate business practices documented in the literature on integrity violations in health to the pursuit of specific legitimate business objectives, distinguishing individual and collective strategies. To operate and succeed, businesses can legitimately seek to: i) promote a business-friendly environment; ii) gain market entry for their products and services; and iii) take action to increase demand for products or services. Figure 7.8 points to the type of inappropriate business practice that can be traced back to each of these strategic objectives.

The question of whether some industries are able to distort legislation in the health sector is controversial, with some observers arguing that the influence of the pharmaceutical industry in Europe and the United States is excessive. A detailed analysis of the means and funding deployed by pharmaceutical firms and trade associations on lobbying at the European level highlighted that they outstrip the resources spent by civil society organisations registered as working on access to medicines and public health issues (EUR 40 million versus EUR 2.7 million in 2014). Over the last two years, civil society organisations in Europe repeatedly expressed concern that changes in intellectual property regulation and other legal provisions envisaged in the context of the EU-US Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) for the pharmaceutical industry could undermine countries’ capacity to regulate pharmaceutical prices, generics competition or the transparency of data on clinical trials (CEO, 2015[58]; Commons Network, 2015[59]). In the United States, the Center for Responsive Politics, which compiles data from the Senate Office of Public Records, shows that lobbying expenditure on health is more than USD 480 million a year (a virtual tie for first place with the banking, insurance and real estate sector).[60] In 2013, a special issue of the Journal of Law Medicines and Ethics contended that institutional corruption has undermined the capacity of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to safeguard public health (Light et al., 2013[61]) and contributes to explaining the content of some legislation (Jorgensen, 2013[62]). Governments’ capacity to act as independent regulators — in health or other sectors — warrants constant attention, including in OECD countries (OECD, 2016[63]).

Circumventing regulation to gain entry into the health care market is a second category of documented problem. Entry into the health sector for a professional or a facility providing health care services is always regulated, primarily to protect patients’ safety but for other reasons as well.[64] Similarly, medical products are subject to marketing authorisations. Potential entrants into the market might be tempted to bribe, exert pressure on or simply use their influence with the regulator. More indirectly, they can manipulate the regulator by proving misleading information. In this domain, leaving aside the relatively simple case of individuals who might present falsified credentials, the main concern in the literature is the strong conflict of interest (CoI) the pharmaceutical industry faces when presenting the results of clinical trials. As part of their research and development process, firms undertake or fund clinical trials to assess the safety and effectiveness of their own products and present the evidence to the regulator to obtain a marketing authorisation. The information can also be used by the payer to include a product on the positive list or in the price-setting process and to influence drug prescription down the line.

Clinical trials must meet quality criteria and are subject to scrutiny by regulatory authorities, but opportunities exist to manipulate data and exaggerate positive findings, underplay negative outcomes or selectively publish results (Lexchin, 2012[65]). Several analyses show that industry-sponsored clinical trials are more likely to yield positive results for their sponsors and have higher citation impact (for a review, see Transparency International-UK, 2016[66]), including trials that compare treatments with one another (Flacco et al., 2015[67]). In recent years, re-analyses of evidence from industry-sponsored trials led to questioning of the efficacy of Tamiflu,[68] and to showing that paroxetine, which had been prescribed to adolescents, was not only ineffective but could cause harm (Le Noury et al., 2015[69]). The latter case was part of a USD 3 billion fraud settlement by GlaxoSmithKline (Almashat et al., 2016[70]). Ebrahim et al. (2014)[71] reviewed 37 published re-analyses of randomised clinical trial data and found that more than a third resulted in changing the conclusions drawn from the information available. A new analysis producing concordant results is less likely to be worthy of publication than one that modifies them, so the proportion is probably artificially high. Further, the revised conclusions do not necessarily contradict the initial findings, but this analysis clearly highlights that published results are not necessarily definitive.

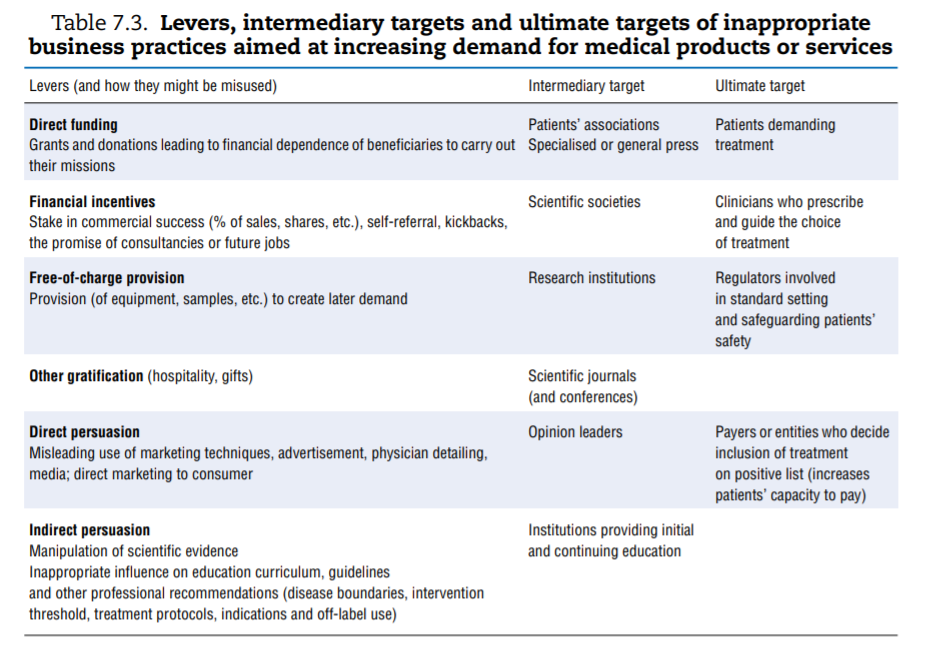

A vast range of inappropriate strategies can be used by providers of medical goods and services to increase demand for their product. Rather than systematically listing them, Table 7.3 offers a synthesis. To increase demand for their products and services, businesses need to convince the final decision makers: patients, who “consume”; physicians, who guide or even prescribe use; regulators, who are in a position to set or validate standards and rules; and payers, who define what can be financed from pooled funds (private or public), hereby ensuring that large contingents of patients can afford the goods or services. Each of these stakeholders can be subject to direct influence (for instance, direct-to-consumer advertising targets patients). Businesses can also seek to influence “intermediary” institutions expected to offer independent and objective input to ultimate decision makers (for instance, patients’ associations, opinion leaders or scientific societies).

The first column of Table 7.3 groups the most common practices documented as leading to abuse. Keeping in mind that inappropriate practices are not necessarily widespread, a few concrete and recent examples help highlight the risk. A final category of inappropriate practice, which consists of delaying or preventing competitors’ entry into the market, is discussed subsequently.

- Direct funding. Patients’ groups, which typically represent the interests of or support people suffering from specific diseases, are perceived by the public to be independente but many are frequently funded by pharmaceutical industries that market drugs used to treat these very diseases. Arie and Mahony (2014)[72] offer some examples of situations where this has created at least the appearance of a CoI.

- Indirect funding and other gratifications. In 2015, the British Medical Journal reported on a hospital in Chicago that provided kickbacks to referring physicians and a group of UK physicians receiving financial inducements in exchange for referrals to a private hospital group (Godlee, 2015[73]). The European Commission (2013)[74] offered additional examples of pharmaceutical companies remunerating or rewarding physicians who prescribed their brand and a 2016 New York Times article shed light on the practice of paying haemophiliac patients in an effort to recruit customers.[75]

- Direct persuasion. Firms operating in a competitive environment use marketing techniques to differentiate their products and appeal to more (or better) customers. A classic example is health insurance companies using marketing techniques to attract healthier patients. For instance, two studies showed that advertising was targeted at, and resulted in, enrolling lower-risk Medicare patients by health insurance plans (Mehrotra et al., 2006[76]; Aizawa and Kim, 2015[77]). Pharmaceutical companies spend considerable amounts on a wide range of marketing techniques, including physician detailing, and can also be tempted to breach good marketing practices (Transparency International-UK, 2016[78]; European Commission, 2013[79]). A review of 25 years of settlements by the industry in the United States showed that a quarter of offences were related to “unlawful promotion”. Most cases pertained to promoting off-label use (which was restricted)[80] or downplaying information about side effects (Alsmashat et al., 2016[81]).

- Indirect persuasion. Indirect persuasion consists of influencing the production of evidence or guidelines that the “ultimate targets” factor into their decision making. The possibility for the industry to influence the dissemination and presentation of clinical trials data was mentioned earlier. Chapter 2 on low-value care discussed the pharmaceutical industry’s role in shaping the social construction of disease and medicalising normal human experience, which can ultimately open new markets. The possibility that manufacturers can influence the production of guidelines that are designed to influence prescription patterns has also drawn attention. The financial relationships between the bio-medical industry and the experts or institutions involved in production of clinical guidelines are “pervasive, under-reported, influential in marketing, and uncurbed over time” (Lenzer et al., 2013[82]; Campsall et al., 2016[83]).

Central to many of these examples is the notion of CoI, defined as a set of circumstances that create a risk that the professional judgment or actions of individuals or institution regarding the accomplishment of their core mission could be unduly influenced by their private interest.[84] As highlighted in the comprehensive analysis of CoI by the US Institute of Medicine, the mere existence of the risk creates a CoI, whether the entity is ultimately influenced or not (IOM, 2009[85]). Indeed, relationships between actors with potential or actual conflicting interests do not necessarily result in inappropriate business practices. In fact, physicians, biomedical researchers and pharmaceutical or medical device companies need to collaborate to develop new treatments that benefit the population. Still, teaching or academic institutions and associated researchers, scientific journals, patients’ associations, health care providers, their opinion leaders and scientific societies can all risk appearing conflicted as soon as they enter into a relationship with industries.

The last category of documented inappropriate practice falls more in the domain of breaches in competition policy. Some brand name pharmaceutical companies and generic drug producers engage in strategies to delay or prevent the availability of cheaper generic drugs, thereby increasing the price paid by patients, governments and insurance companies. These practices involve brand name companies paying would-be generics competitors to delay entering the market, securing a longer period of exclusivity and high profits. Alternatively, generics producers can be bought out by brand name companies. Depending on circumstances, such practices infringe competition law and on a number of occasions the involved companies were forced to return the unduly earned profits (Jones et al., 2016[86]). Based on the known cases, in the United States alone, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) estimated that such practices add at least USD 3.5 billion annually in higher medicine prices. A 2009 EU inquiry estimated that savings due to generics entry could have been 20% higher than they actually were, if entry had taken place immediately following loss of exclusivity (European Commission 2009[87], 2016[88]).

Drug companies combine these forms of inappropriate business practice with “product hopping”, also called “ever-greening”. This involves making minor variations to a drug prior to its patent expiration (for instance, by patenting a slightly different tablet or capsule dose) and obtaining new patent protection without adding any therapeutic advantage. Pay-for-delay in connection to product hopping can mean that by the time a potentially competitive generic drug enters a market, the originator product is transformed such that the substitution is not legally possible (in most countries, a clinician can only substitute a brand name drug with a cheaper generic drug if the latter has exactly the same dosage strength).

3.2. Regulation and emphasis on transparency play an increasing role in tackling inappropriate business practices

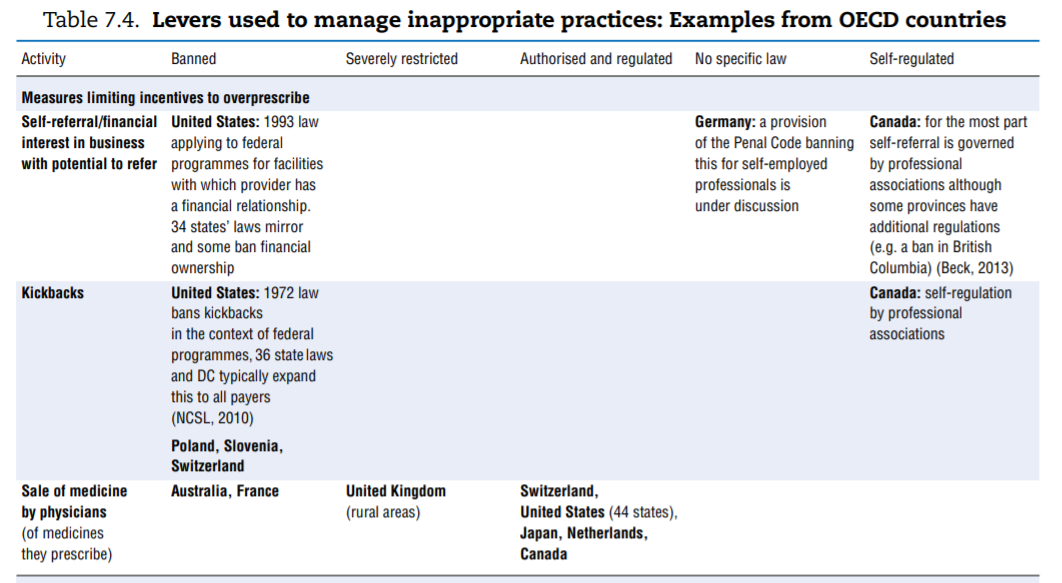

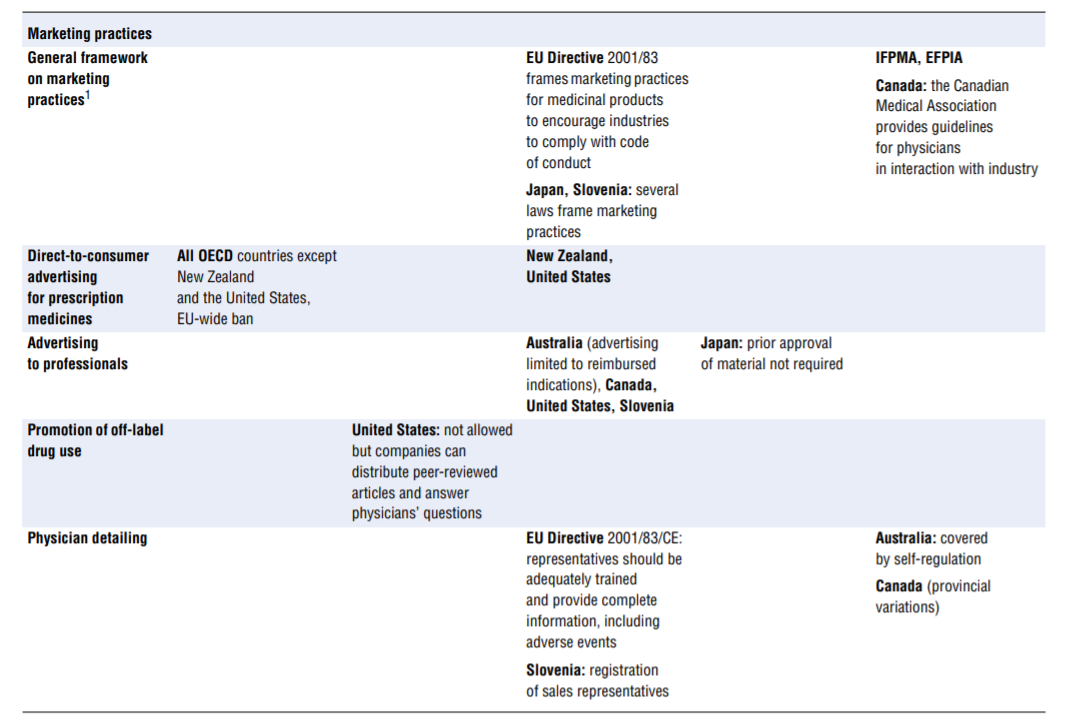

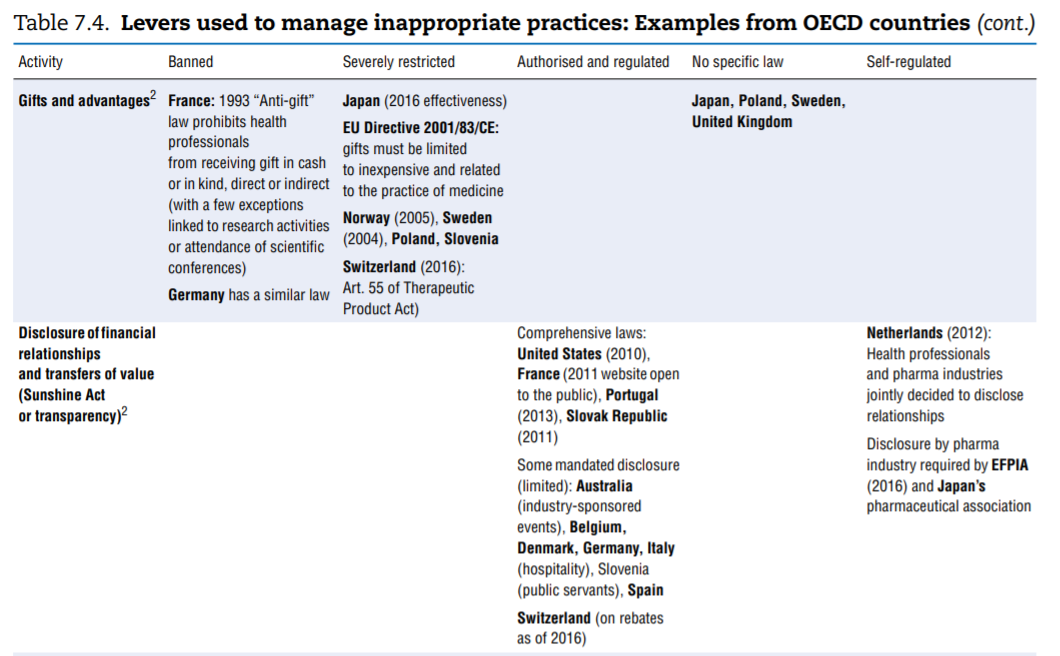

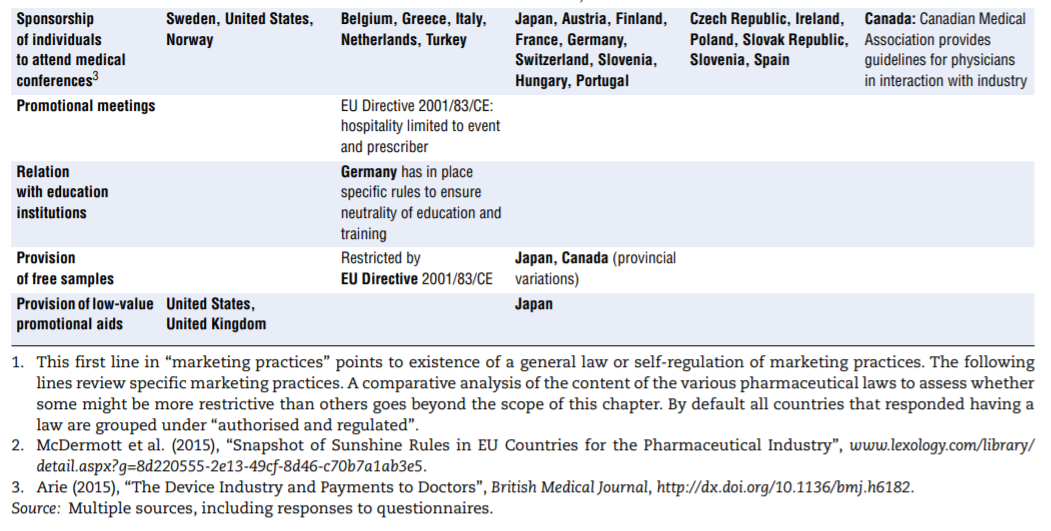

No comprehensive information is available about policies aimed at tackling inappropriate business practices across OECD countries. The literature review undertaken to fill the gap as well as the responses received from 15 countries to the OECD 2016 questionnaire give a sense of the policy levers some countries use to discourage inappropriate business practices, but the picture is far from comprehensive. Table 7.4 presents the information collected. This final section highlights the first lessons drawn from the exercise. The overall conclusion is that countries rely primarily on self-regulation to manage inappropriate business practices but many countries do have some regulations in place to ban or limit specific practices. These sector-specific regulations tended to develop over time and many countries are considering introducing them. Finally, pressure to increase the transparency of clinical trials is growing.

Most countries rely significantly on self-regulation to prevent inappropriate business practices

Self-regulation is at the core of the strategy used across OECD countries to deter inappropriate business practices. This self-regulation originates either from industry itself in the form of codes of conduct or from institutions or professionals who may face a CoI and adopt CoI policies. In some instances, CoI policies are laid out by governments to cover civil servants or individuals in a position to advise the government.

Codes of conduct are widespread among pharmaceutical associations, but less visible in the medical device industry. Over the years, the pharmaceutical industry’s professional associations worldwide developed and encouraged adherence of individual firms to codes of conduct. The International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA) code of conduct, last revised in 2012, includes provisions on interactions with health care professionals, medical institutions and patient organisations

(Francer et al., 2014[91]). All member associations are required to adhere to the minimum principles laid out in the code of conduct — provided they are not in contradiction with countries’ legal framework and recognising that individual codes can include additional provisions. In turn, individual industries registered with these associations are required to adopt a code of conduct based on these guidelines. Operating along these principles, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) — a member of IFPMA — developed its own code of conduct. It contains more stringent requirements and in particular, as of 2016, requires all member companies to disclose transfers of value to health care professionals and health care organisations. All OECD countries follow either a code formally aligned with those of IFPMA or EFPIA or ones seemingly developed independently (in the case of Israel, Luxembourg and New Zealand). For the medical device industry, the practice of encouraging the development of codes of conduct does not seem as well organised. MedTech Europe, an alliance of European medical technology industry associations, developed a new code (combining two previous ones) that will come into force in 2017.

Little is known about the take-up or effectiveness of codes of conduct. Adherence is ultimately a company’s decision and no data on the proportion of firms that actually adhere to a code are readily available. Codes of conduct generally provide for the possibility of a complaints mechanism in case of breach but again, little information is available about the frequency of complaints (if any), the sanctions taken or their impact.

Self-regulation is used by all stakeholders at risk of CoI: physicians, experts, advisors to policy makers, academic and research institutions and medical journals. The US Institute of Medicine undertook an in-depth analysis of CoI in medical research, education and practice and in the development of clinical practice guidelines (IOM, 2009[92]).

Among its key conclusions, the report highlighted that:

- Preventively dealing with CoI helps protect stakeholders’ integrity and increases trust in the institutions they represent.

- Disclosure of financial interest is a critical but insufficient element of a CoI policy; institutions at risk should be mandated to develop explicit CoI policies. As relevant, these policies should include prohibition of specific practices, guidelines for management of specific situations (for instance, individuals who have or may be perceived to have a CoI should not participate in the relevant decision making), and creation of committees to evaluate and manage CoI.

- Mandates to implement CoI policies are not always effective and their content is not always strong enough to achieve their purpose.

- CoI policies can put a significant burden on providers.

CoI policies are not only the domain of self-regulation. In fact, a number of countries put CoI policies in place for civil servants in general (e.g. Australia, Belgium — law of 2002, Poland and the United States) and codes of conduct for professionals (for instance, in German Länders) and/or for people who act in an advisory position to Ministries of Health or related institutions. Responses to the questionnaire mentioned that disclosure of interest is mandated as follows:

- In Australia, for officials of the National Health and Medical Research Council (which funds research and establishes guidelines); the Department of Health also mandated CoI provisions and policies for all its employees and members of external advisory committees.

- In Belgium, for members of the Commissions and linked Working Parties and Subcommittees competent in the reimbursement of pharmaceuticals and medical devices.[93]

- In Norway, for the Norwegian Medicines Agency

- In Slovenia, for advisors to the Ministry of Health and board members in public institutions (since 2015); and in Poland, for consultants (physicians operating in an advisory capacity to the government).

- In France, which expanded measures over time; a harmonised disclosure formmust now be filled by all individuals working for or advising all health-related administrations since 2011; these declarations are made public.

- In contrast, Germany does not have sector-specific measures in place.

Governments regulate specific practices but not uniformly

Considerable variation arises in the way countries deal with situations, which can generate CoI or inappropriate practices. Table 7.4 highlights the range of approaches used to deal with a list of specific situations and activities. The list was established based on evidence that some countries had explicitly put such measures in place, but the list may not be exhaustive. Potentially inappropriate practices fall into two categories:

- Activities that leave a possibility for a provider’s recommendation to a patient regarding a treatment to be overly self-interested, such as:

❖ receiving payments for referrals or prescriptions (kickbacks)

❖ selling medicines (physicians)

❖ having financial ties with an entity that can gain from one’s prescription or being allowed to refer to an entity with which one has such ties (e.g. a private hospital).

- Marketing practices. In many — perhaps even all — countries, guidelines frame the marketing of medicinal products. For a start, the pharmaceutical industry’s codes of conduct, which exist in all OECD countries, typically cover a common set of core issues, including the obligation to provide truthful and balanced information about marketed products. Marketing practices are probably covered in some form of government regulation in most countries. As part of these, or in addition, a number of practices are identified on which countries clearly put more or less emphasis, in particular (see Table 7.4): direct-to-consumer advertising, advertising to professionals, physician detailing, gifts and advantages, sponsorship of individuals to attend medical conferences, promotional meeting/conference sponsorship, provision of free samples and provision of low-value promotional aids.

The columns of Table 7.4 list regulatory responses in order of decreasing strength:

- Bans. Some countries simply choose to ban specific activities that are at too high a risk of generating inappropriate behaviours. This is the case for dispensing of medicines by physicians (Australia and France) and for sponsorship of health professionals to attend educational events (Norway, Sweden and the United States).

- More or less severe restrictions. The distinction between “severely restricted” and “authorised but regulated” is probably arbitrary but Arie (2015)[94] introduces it when describing across countries the rules surrounding sponsorship of conference attendance. In some countries, the regulation may consist of requesting employers’ authorisation to attend, banning the funding of relatives’ travel expenses, or setting a limit on the total amount payable for hospitality. In others, all these rules apply simultaneously, which is more restrictive.

- No restrictions. In some instances explicit mention was made that a given practice was not subject to regulation (often in contrast to other countries).

- Self-regulation. Self-regulation may coexist with government-dictated regulation but in some cases it is the only framework governing the activity.