Financial Times

November, 2021

Within hours of sounding the alarm over the new Omicron variant of Covid-19, Tulio de Oliveira, the scientist helping to steer South Africa’s pandemic response, was fielding calls from biosecurity agencies worldwide asking for live samples.

“We have always [been] very collaborative . . . so the key questions can be answered as fast as possible”, says de Oliveira, a bioinformatics professor at Stellenbosch University.

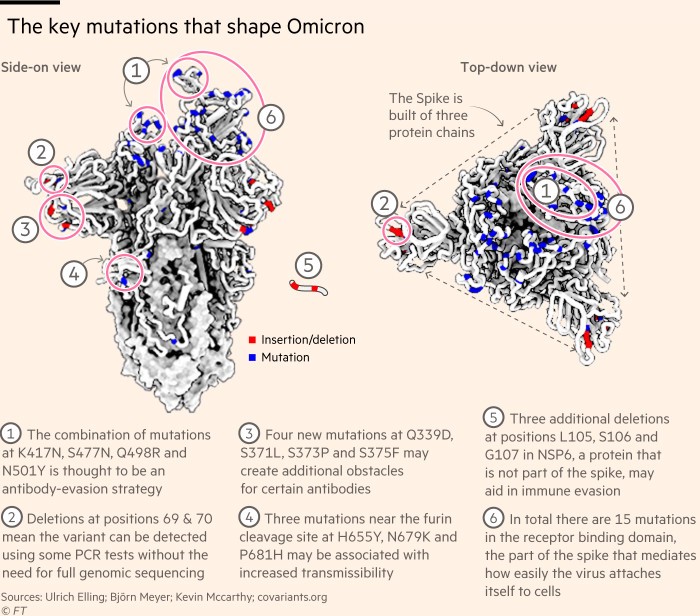

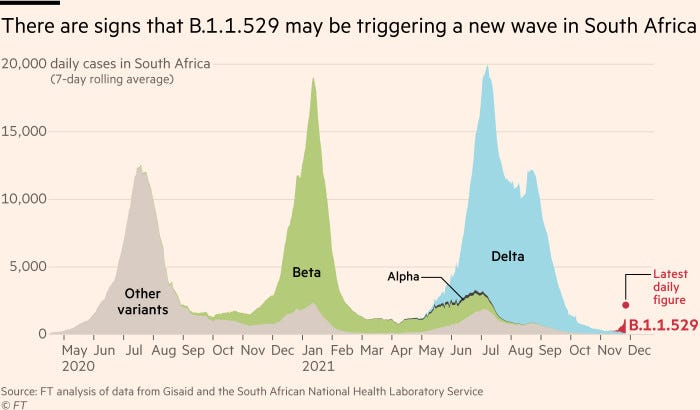

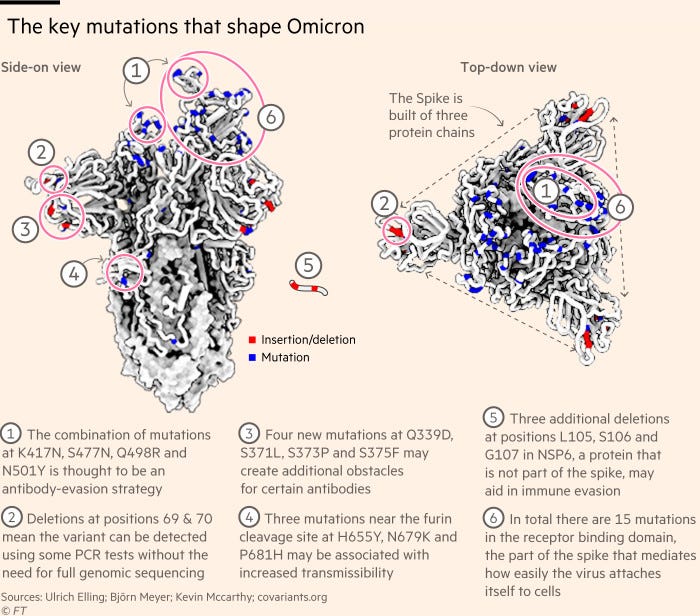

De Oliveira’s colleagues have been working round the clock to cultivate the new strain of the heavily-mutated virus, designated B. 1.1.529.

Packages will be urgently dispatched to the US National Institutes of Health facility in Bethesda, Maryland and the UK Health Security Agency laboratory at Porton Down.

But, despite the ease of cross-border scientific collaboration over Omicron, some global health experts fear the international law on pathogen sharing is more likely to hamper, rather than hasten, the development of diagnostics, drugs and vaccines to combat future pandemic threats.

Their anxiety centres on the rules enshrined in the Nagoya Protocol, a legally binding agreement that guarantees 196 signatory countries access to the products of scientific research done on plants, animals and genetic resources — including pathogens — emerging from their territory. The US is one of the few major nations that never signed up to the protocol.

This week, policymakers from around the world will meet at a special session of the World Health Assembly to discuss global preparedness for the next pandemic, and the hotly debated idea of reforming the Nagoya Protocol will be on the table.

The protocol, which was added to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2014, calls for signatories to be “mindful” of public health emergencies.

However, scientists and pharma industry leaders say it is too open to exploitation by countries looking to barter over pathogens.

“Some countries consider pathogens a genetic resource under the protocol [and], as a result, are controlling who can access them and when,” says Thomas Cueni, director-general of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA).

“Imagine if researchers wishing to understand quickly if our vaccines are effective against Omicron had to start negotiating ‘mutually agreed terms’ and request ‘prior informed consent’ from South Africa,” he points out.

“The benefits of pathogen sharing could not be clearer,” Cueni argues. “We should not leave it to chance that a government, one day, holds back a dangerous virus so that it spreads, and then gets royalties for all the vaccines developed to protect people from the very virus they withheld.”

Originally published at https://www.ft.com on November 29, 2021.