The Health Strategist

the blog of Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

December 16, 2021

- Which countries are best protected against Omicron?

- Scientists see a ‘really, really tough winter’ with Omicron

- The Omicron variant advances at an incredible rate

(1) Which countries are best protected against Omicron?

Boosters, or a combination of infection and vaccination, are needed against the new variant

Financial Times

December 15, 2021

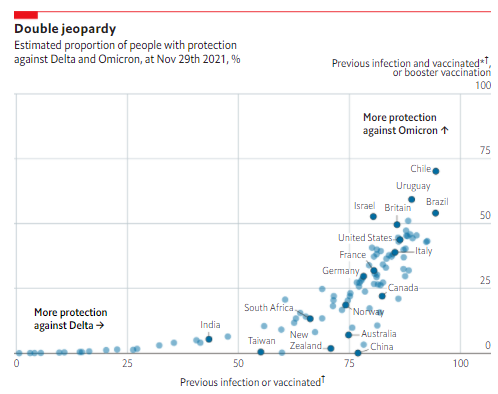

Key messages

- South American countries with high levels of previous infection and good vaccination rates seem best prepared for the new variant. Chile and Uruguay also have among the most advanced booster programmes, in part because they started earlier than most after reports that the Chinese Sinovac jab, given to many of their citizens, had lower efficacy. In most countries it is likely that less than half of people have adequate protection against Omicron.

- In Britain and America we estimate that, at the end of November, around 49% and 43% of citizens respectively had either had a booster, or been double jabbed and infected.

- Countries like Australia, China, New Zealand and Norway, with strong vaccination programmes but few prior infections and a slow rollout of boosters, are particularly vulnerable to the new variant. ■

FOR MOST of 2021 people who had completed a course (usually two doses) of covid-19 vaccines were considered to be protected against the disease. People who had already been infected were also thought to be fairly safe. But by evading previous immunity, Omicron, the newest variant, has changed that calculation. That means a reassessment of how vulnerable countries may be.

Omicron has a constellation of mutations that change both how it spreads and its symptoms. Early evidence suggests that infections from this variant may be causing fewer cases severe enough to require hospital admission. But the mutations it contains also make it more transmissible. And lots more cases of a disease that is less often severe can overwhelm hospitals too. Omicron is better than other variants at evading antibodies produced by previous infection with covid or by vaccination against it. Studies from Britain and South Africa have shown that this translates to between three and eight times greater risk of reinfection than the previous Delta variant. And data from Britain show that the level of protection against symptomatic infection after two doses of either the AstraZeneca-Oxford or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, among the best against Delta, falls substantially when faced with Omicron.

There is some better news. Although there is a big decrease in the protection provided, results from South Africa show that previous infection still cuts the risk of catching Omicron by around two-thirds. Furthermore, vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic infection is restored to 75% by a booster dose. There are also hints of good protection for people who have been double jabbed and had a previous infection, although immunity does wane over time.

These changes in the definition of good protection require new ways of assessing which countries are the best defended against the coming wave of infections. Countries that are well protected against Delta are those with high numbers of people who were either double jabbed or previously infected. Countries that are likely to have the best protection against Omicron are those that have administered lots of boosters, or have many people who have been both double jabbed and previously infected.

For 102 countries we estimated the percentage of the population that might have these different levels of protection. Using data on the likely number of infections in the country and the number of people who have received vaccinations, we calculated the probability that a given citizen had been infected, vaccinated or both. For simplicity, we make the assumption that a person’s decision to get vaccinated is not correlated with whether they have been infected.

South American countries with high levels of previous infection and good vaccination rates seem best prepared for the new variant. Chile and Uruguay also have among the most advanced booster programmes, in part because they started earlier than most after reports that the Chinese Sinovac jab, given to many of their citizens, had lower efficacy. In most countries it is likely that less than half of people have adequate protection against Omicron.

In Britain and America we estimate that, at the end of November, around 49% and 43% of citizens respectively had either had a booster, or been double jabbed and infected.

Countries like Australia, China, New Zealand and Norway, with strong vaccination programmes but few prior infections and a slow rollout of boosters, are particularly vulnerable to the new variant. ■

For a look behind the scenes of our data journalism, sign up to Off the Charts, our weekly newsletter

Originally published at https://www.economist.com on December 15, 2021.

(2) Scientists see a ‘really, really tough winter’ with Omicron

Another major pandemic wave seems inevitable. The big question is how much severe disease it will bring

14 DEC 2021

BYKAI KUPFERSCHMIDT

When South African scientists first alerted the world to the rapid spread of a new SARS-CoV-2 variant, some speculated it might not take off in other countries. After all, an earlier variant named Beta, which dominated in South Africa between November 2020 and May, did not spread much beyond its borders and has since petered out.

Today it’s clear that the world will not be so lucky this time. Although many questions remain, scientists feel increasingly confident that the new arrival, Omicron, is likely to dramatically alter the trajectory of the pandemic — and not for the better.

Omicron has now been found in more than 70 countries and is rapidly gaining ground. As Science went to press, for example, Danish scientists estimated Omicron was just days away from replacing Delta as the most common variant. “What we see is an extraordinary, rapid spread,” says Troels Lillebæk, an infectious disease researcher at the University of Copenhagen. Despite very high vaccination rates, the country of 5 million is now seeing more than 6000 cases a day, roughly twice the number seen during the highest previous peak. (The growth seemed to show signs of slowing down early this week, but that may be in part because the country is reaching the limits of its testing capability.) Neighboring Norway, which has about the same population, is now projecting more than 100,000 cases a day in a matter of weeks, unless people drastically reduce social contacts.

Even if Omicron causes milder disease, as some scientists hope, the astronomical case projections mean the outlook is grim, warns Emma Hodcroft, a virologist at the University of Bern. “A lot of scientists thought Delta was already going to make this a really, really tough winter,” she says. “I’m not sure the message has gotten across to the people who make decisions, how much tougher Omicron is going to make this.”

For Hodcroft and other virologists, immunologists, and epidemiologists, Omicron is another dizzying plunge on the pandemic roller coaster, right before the holidays — a time of frenzied phone calls, late night work, and little sleep. “We have people working the whole weekend again,” says Florian Krammer, a vaccine researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “It doesn’t matter if something needs to be done at 10 p.m., it’s getting done.”

As with earlier variants, a handful of countries are providing the world with most of the early data. South Africa, where scientists first observed the spread of Omicron, has sequenced a wealth of genomes and produced data about early cases. Denmark, with one of the best genomic surveillance systems in the world, has provided an in-depth view of how Omicron can explode on top of a Delta surge. And scientists in the United Kingdom are conducting a host of studies to nail down how well Omicron transmits in households and elsewhere, and how vaccines are doing against the variant. “We should be pretty grateful” to these countries, Hodcroft says.

As a result, Omicron’s key properties are becoming clearer by the day. It’s beyond doubt that the variant has a substantial growth advantage. What’s less clear is whether that’s mostly because it can evade the human immune response or also because it is inherently more transmissible than its predecessors. That may not matter in the short run, but it does for the long-term outlook. If it’s all about immune evasion, Omicron’s advantage over Delta could wane as immunity to it builds up, and the two could end up cocirculating. If Omicron is also more infectious, it may replace Delta, just as Delta displaced earlier variants.

How good Omicron is at immune escape is also becoming clearer. Preliminary data from South Africa showed its rise coincided with an unexpected surge in reinfections. This past week, laboratory assays by several groups have shown antibodies, whether elicited by vaccines or a previous infection, are significantly less effective at neutralizing Omicron than other variants. And based on the first cases, scientists in the United Kingdom have estimated that protection from symptomatic illness is much lower in people who have received two doses of the AstraZeneca or messenger RNA vaccines. The good news is that boosters appear to bring protection against disease back to about 75%, and probably even higher against hospitalization. “I think it all boils down in the end to protection from severe disease,” Krammer says.

Early data from Discovery, South Africa’s largest health insurer, presented on 14 December, offered some additional reassurance that Omicron’s immune escape isn’t complete. The data showed hospital admissions in the country are growing more slowly than in previous waves. That could mean the protection from severe disease is still robust in vaccinated and recovered people — or the virus is inherently a bit milder than Delta.

But Harvard University epidemiologist William Hanage says the question of severity is still impossible to answer. Recent genomic comparisons suggest Omicron only began to spread in mid-October — earlier work had estimated late September — so the variant hasn’t infected enough people to conclude much of anything, he says. By chance, many of the early cases in South Africa happened to be in younger people, who are less likely to develop severe disease. And even if the variant turns out to be inherently milder, the volume of cases will likely overwhelm health systems. “A colleague put it really well in one of our little depressing Slack channels,” Hanage says: “There’s not much that can spread this fast and be benign to a society that’s already got full hospitals without it.”

Scientists also worry Omicron — which represented a massive leap from known variants in genomic terms — may bring other, unpleasant evolutionary surprises. For instance, roughly one-tenth of Omicron genomes sequenced so far have an additional mutation in the spike protein called 346K that is predicted to make it even better at evading the immune system. “Omicron has most of the greatest hits for antibody escape already, so there aren’t a ton of additions that it could make, but 346K is one of them,” says Stephen Goldstein, a virologist at the University of Utah. “We have to keep an eye on it.”

Given its divergence from earlier variants, Krammer thinks vaccine manufacturers should develop booster shots tailored to Omicron. Obtaining regulatory approval and making such boosters available in large numbers would take months, however — too long to address the crisis many scientists expect. And if the past year is any indicator, they are unlikely to be available to low- and middle-income countries in any meaningful quantities.

For now, most European countries are hoping that providing existing boosters widely, in tandem with added control measures such as a ban on large gatherings, mask mandates, better ventilation, and working from home, will help lower the wave of Omicron infections and prevent hospitals from buckling. Maria Van Kerkhove, an epidemiologist at the World Health Organization, says vaccinating those who have not received any shots at all is still very important — even though it may be too late to get the numbers up substantially. “Get the vaccine into the arms of people who are most at risk,” Van Kerkhove says. “Look to see who you’re missing and focus on these.”

Originally published at https://www.science.org

(3) The Omicron variant advances at an incredible rate

The Economist

December 18 week, 2021

E XPONENTIAL GROWTH is a dizzying thing. In the week to December 8th Britain saw 536 new cases of covid-19 ascribed to the Omicron variant, less than 0.5% of the number caused by the dominant Delta variant.

But the week before there had been only 32 cases of Omicron-and by December 14th the case number was over 10,000.

Omicron looks set to become the country’s dominant strain in terms of cases before advent calendars run out of windows.

Cases lag behind infections. On December 13th Britain’s health minister, Sajid Javid, said that there were estimated to have been 200,000 infections in the country that day, most of them Omicron. Three more doublings and the total number of infections a day will be more than 1m.

It is not just in Britain that Omicron is outstripping Delta. It has already displaced it in South Africa, where it first came under scrutiny and where its growth, though possibly now slowing a little, has been spectacular.

Studies in various European countries show similar growth, though with a later start.

The same is true in America.

The variant has now been detected in almost all countries, including China.

The numbers involved are often small. But with exponential growth small is not much comfort: it doesn’t last.

Omicron seems to have two attributes that enable such rapid spread. Some subset of its many mutations seems to make it more transmissible. Contact-tracing studies in Britain have found that the risk of a given Omicron infection spreading is two to three times that for a Delta infection.

And because it is better at infecting people who have previously been vaccinated, or infected, it has a larger pool of people to infect. On December 14th Discovery Health, South Africa’s largest health insurer, produced the initial results of work on Omicron undertaken with the South African Medical Research Council. They found that, whereas two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech m RNA vaccine offered 80% protection against infection before the Omicron wave, against Omicron the protection dropped to 33%. Its effectiveness in reducing the risk of severe disease is also lower: two doses of the Pfizer vaccine reduced the risk by 70% (down from 93% for Delta).

That still makes being vaccinated a very good thing. Most of the people who have been hospitalised with Omicron in South Africa, and 84% of those in intensive care, are unvaccinated. And it does not look as if the sort of vaccine someone was given matters all that much. The other vaccine in use in South Africa, made by J&J, an American company, relies on a modified adenovirus, rather than m RNA, to get its message into the body, as does the more widely used AstraZeneca vaccine. It, too, seems to protect against severe disease.

These real-world findings support the hope that two doses of all the existing vaccines will continue to offer significant protection against severe disease, even if they are not so good at blocking infection. That makes sense. Evolution has shaped the immune system to reduce the risk of death. Stopping a virus which the body has seen before from infecting it again is a helpful step in that direction, and one of the primary purposes of the antibody response. But it is not the only step; the defence is deep and layered. Incoming Omicron may be good at evading the antibodies produced by vaccines and previous infections-it is 3–8 times more likely to infect someone who has previously been infected than other variants. But further foes await it.

After infection has started, cell-based immunity joins in the fight, seeking out and destroying the cells which the virus has suborned. This response is greatly strengthened by prior vaccination. And it is less easily fooled by a few changes to the proteins on the virus particles’ surface. That is why vaccines can still protect against disease even if the antibodies they provoke no longer recognise the pathogen as well as they did originally, or if they have waned over time.

That said, a better antibody response would be nice to have; slowing the rate of infections would slow the spread of disease and give health systems breathing space. This is where vaccine booster shots come in. Boosters improve all forms of immunity: one of their effects is to raise antibody levels, at least for a while. This increased quantity can go some way to making up for the reduced quality of their response, lowering the risk of infection. Boosters may improve the quality of the antibodies, too; the more the immune system sees a virus, the better attuned to it some antibodies become.

A reasonable expectation that vaccines offer protection against serious disease, especially after a third jab, is one piece of good news. Another may be that Omicron infection leads to less severe disease all round. There is some evidence of this from Gauteng, the South African province where the variant has run rife. Data from Discovery Health suggest adults with Omicron have a 29% lower hospital admission risk relative to that seen in the country’s first wave of covid-19 in mid-2020. The proportion of those hospitalised who end up in intensive care is much lower than in previous waves, too, and fewer of those on general wards need supplemental oxygen. Angelique Coetzee of the South African Medical Association, who was one of the first to raise the alarm about Omicron, has consistently argued that it is a milder variant.

A paper recently submitted for peer review by Michael Chan and colleagues at Hong Kong University suggests one reason why this might be.

- They found that in the first few days of infection Omicron reproduced 70 times more readily than Delta in the airways leading to the lungs.

- But in the lungs themselves it reproduced ten times less well than earlier variants.

The details of how viruses cause disease depend on a lot more than simple reproductive rates. But this finding might go some way to explaining a lower incidence of severe disease; it is infection in the lungs that does most damage. And greater replication higher up the respiratory tract might improve transmissibility. Being very good at getting into, and reproducing in, the lining of the airways could make it easier for the virus to set up shop in someone exposed to it. What is more, a lot of activity in the airways might also mean more particles get back out into the air. Indications that the symptoms of Omicron infection are more like those of the common cold might fit with this interpretation.

But neither that laboratory work nor the data from South Africa amount to a strong case that Omicron will be a lot less dangerous than earlier strains everywhere. The South African data are preliminary; so far they cover only the first three weeks after infection. Typically, new waves of covid variants start in younger groups and work their way into older, more vulnerable populations over time. And the rates at which infection leads to severe disease and death can differ between countries and populations. Factors at play beyond the youth of the South Africans might include the fact that most vaccinations in the country are relatively recent and the fact that a fair number have been previously infected. There may also be salient factors stemming from genetic variation or prior health histories. Things could look quite different in older populations elsewhere in the world which have seen fewer infections.

Da capo, molto vivace

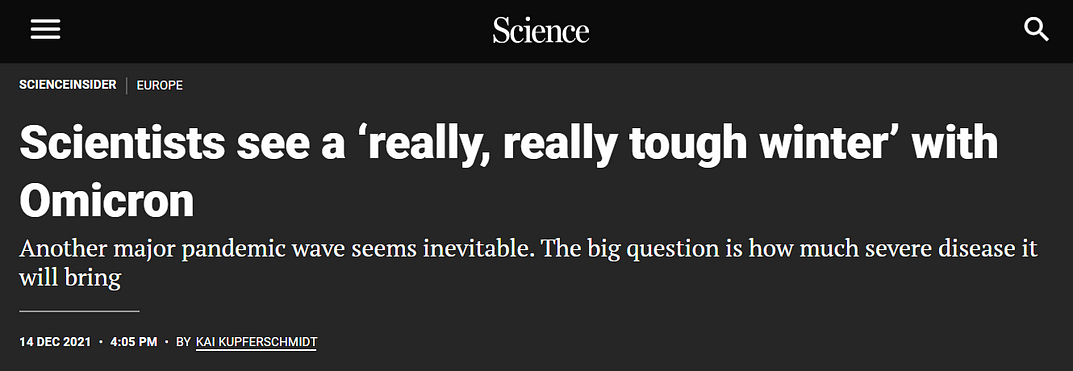

The degree to which the variant can infect the previously infected may also make things look rosier than they really are. Natalie Dean, a biostatistician at Emory University, points out that Omicron’s success at reinfecting people may give the impression a smaller fraction gets severely ill just by inflating the denominator. It could thus seem more benign even if, among those contracting covid for the first time, it were just as dangerous as Delta (see chart).

As the debate about the comparative severity of the infection goes on, public-health officials are stressing that what matters to the individual and to the health system are not all that well aligned. For an individual, a less deadly variant is preferable to a more deadly one, regardless of how transmissible it may be. For a health system, the number of cases at any given time is a critical concern, which makes the rate of transmission crucially important. There is a level beyond which the system cannot cope with the number of hospitalisations. A fast-spreading virus can reach that level even if it produces a lower proportion of severe cases simply because the total number of cases at any given time is so high.

To provide a sense of this, researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine have compared models for the spread of Omicron with the situation in England during the worst previous peak, in early 2021. Of their various scenarios, the one which currently looks most plausible makes Omicron pretty good at infecting people who have been vaccinated or infected but also treats boosters as being quite good at stopping it. That would produce a peak in hospital admissions in late January well over the 3,800 a day seen in 2021. It would lead to 23m-30m infections between now and May 2022, and 37,000–53,000 deaths. Models from the same team have, in the past, proved overly gloomy, but they believe they understand why and have made appropriate adjustments.

The prospect of hospitalisation rates that high saw England go into two national lockdowns, one in November 2020 and one in January 2021. This time the government has recommended working from home and reintroduced some infection-control measures, such as mask-wearing on public transport. It may introduce more. Its greatest stress, though, is on a hell-for-leather dash to provide booster shots to all adults by January 1st.

In a report published on December 15th the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control warned that a range of enhanced precautions were now necessary, including reduced contact in social and work settings, fewer large gatherings, more mask-wearing and more testing. Reducing travel and mixing between households and generations over the holidays may also be on the cards. Some countries are sure to see tougher measures soon; some individuals are already taking them. But if the perception that Omicron is not so dangerous-whether well founded or not-becomes widespread, people may see little reason to adhere to stricter rules.

Countries where Omicron rates are still very low have a little more time to prepare, to learn from those further along the curve, and to estimate what is necessary to flatten and lower the peak. But the growth rates seen so far strongly suggest that time is best measured in days, maybe weeks. Exponential growth is a dizzying thing. ■

This article appeared in the International section of the print edition under the headline “Seeing the need for speed”

Originally published at https://www.economist.com on December 18, 2021.