BCG – Boston Consulting Group

By Ben Horner, Wouter van Leeuwen, Maggie Larkin, Julia Baker, and Stefan Larsson

SEPTEMBER 03, 2019

Introduction

As health systems around the world strive to improve health care value, one of the biggest obstacles they face is the way that individual clinicians and provider organizations are paid for the care they deliver.

Value in health care is generated by delivering better health outcomes for the same, or a lower, cost.

Yet, providers have typically been paid for the activities they perform-irrespective of whether those activities deliver value to patients.

In many countries, most physicians are still paid according to the traditional fee-for-service model.

And even where clinicians are salaried, their employers are reimbursed for the tests and procedures that their salaried clinicians collectively perform, regardless of the outcomes those activities produce.

The problem is not only that activity-based payment models lack incentives for improving health care value but also that they create powerful disincentives for doing so.

To cite one dramatic example, an analysis of more than 34,000 in-patient surgical procedures at a major US hospital system found that privately insured surgical patients with one or more complications provided the hospitals with a profit margin that was 330% higher — an additional $39,000 per patient, on average — than the margin from similarly insured patients who had no complications.[1]

In other words, the reimbursement system made it economically irrational to improve health care value by minimizing complications.

New value based payment models

To address these disincentives, health systems around the world are experimenting with new value-based payment models.

- They are paying performance bonuses to reward providers for meeting predefined thresholds for quality care.

- They are designing bundled payments that reimburse providers for all the activities associated with discrete episodes of care (for example, joint replacement), both to encourage more innovative and cost-effective treatments for the full cycle of care and to hold providers accountable for the ultimate health outcomes delivered to patients.

- And in some cases, they are paying lump sums that cover all of the expected costs to serve certain patient populations, creating incentives for providers to invest in prevention, early diagnosis, and proactive treatment in order to minimize total costs to the system.

The amount of experimentation and innovation in designing new value-based payment models is impressive. To give just one example, in a recent survey of US health care executives and clinical leaders, respondents reported that,

- on average, value-based payments constitute about a quarter of their organization’s revenues, and

- 42% said they believe that value-based payment will eventually become the primary revenue model in US health care. [2]

But it’s fair to say that the results of all this innovation have, so far, been decidedly mixed.

Not all value-based payment initiatives have resulted in improvements in health care value, and it is unclear why some programs have worked while others have not.

Meanwhile, much of the discussion about value-based payment focuses on the relative merits of various payment models.[3]

But the high degree of definitional inconsistency makes it difficult to compare payment models and draw conclusions about their relative efficacy.

The implementation challenge, at the level of an entire health system

When it comes to value-based payment, perhaps the greatest challenge that health systems face today is how to implement value-based payment models at the level of an entire health system.

Even when individual payment initiatives demonstrate improved health care value, it is not immediately obvious how to knit them together into a comprehensive and coherent system-wide payment regime.

For example, what is the best way to organize payment for a patient with comorbidities who may use multiple parts of the health system-primary and acute care, or elective and emergency procedures-often concurrently?

So far, the global health care sector lacks clear, actionable strategies for health systems that want to implement value-based payment models at regional or national levels.

That system-wide level is the focus of this report.

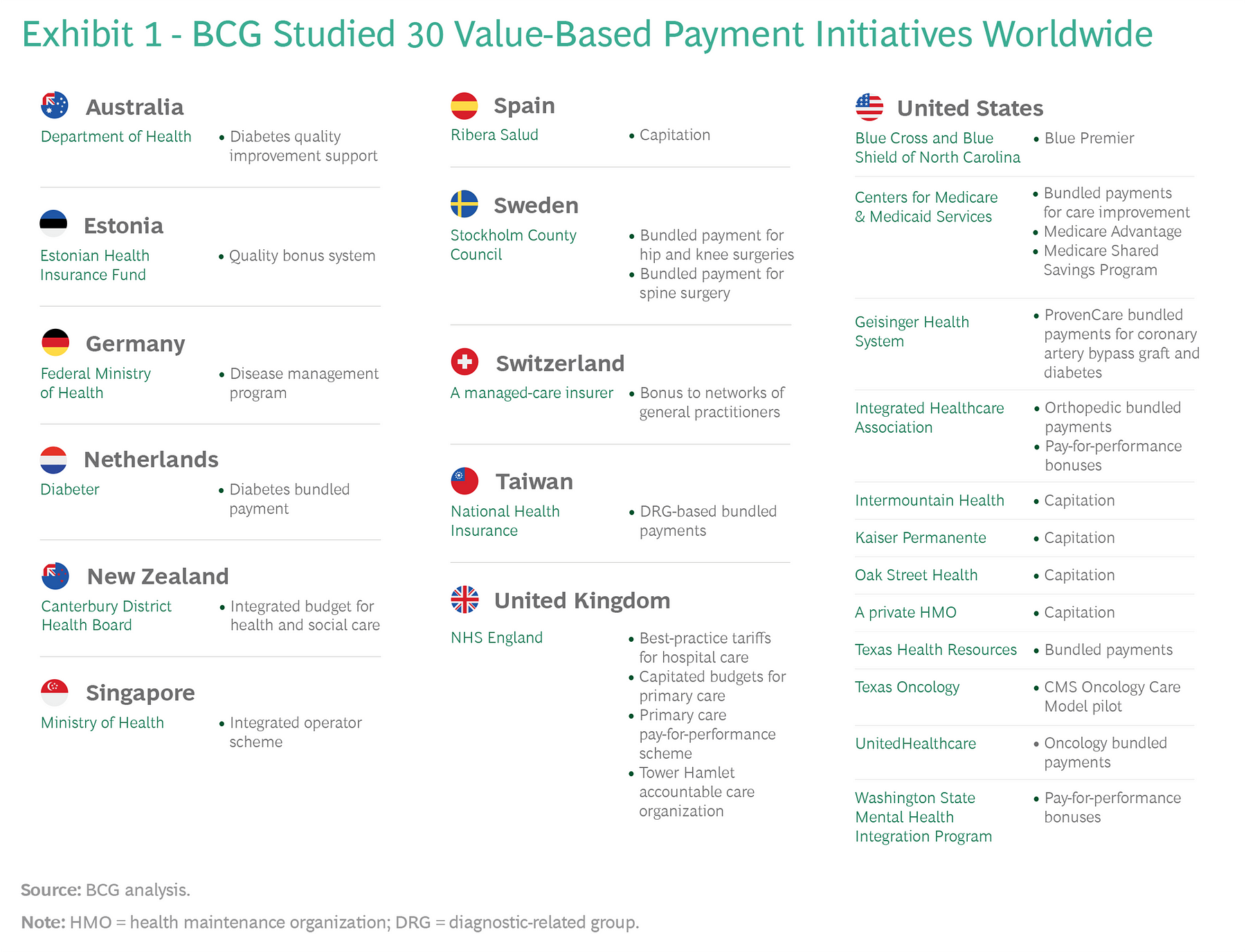

During the past year, BCG studied 30 value-based payment initiatives worldwide and reviewed the growing scientific literature about payment models.

We looked at programs initiated by public and private payers covering single provider organizations and multiple organizations, and by governments that are leaders in value-based health care as well as others that are just beginning to focus on value. (For a list of initiatives studied, see Exhibit 1.)

In addition to creating a clear and consistent taxonomy of value-based payment models, we identified best practices both within and across models and analyzed how various models can be linked together into a coherent system-wide design.

Our research led to three high-level conclusions:

- 1.Value-based payment isn’t an end in and of itself but, rather, a means to an end: creating a new organizational context in which improving health care value becomes a rational behavior for all stakeholders.

- 2.When it comes to changing behavior, financial incentives matter-but so do organizational cultures, norms, practices, and data and analytics.

Therefore, it is critical not to conceive of value-based payment in isolation but, instead, to see it as just one element in a broad system transformation that will require considerable investment and long-term institutional commitment. If initiatives are conceived narrowly as a way to achieve immediate short-term cost-savings, they are likely to fail.

- 3. No single value-based payment model is appropriate for all situations or all patient groups; rather, the challenge is to choose the right type of model for a given situation or patient group and to link different models together into a comprehensive value-based payment system.

In this report, we review the existing value-based payment models and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each.

We then identify seven characteristics of successful value-based payment initiatives. We also propose three pragmatic interventions that leaders can use today to build coherent value-based payment systems-regardless of their organizations’ starting points or existing capabilities.

Finally, we discuss some common system challenges that leaders will encounter.

Varieties of Value-Based Payment

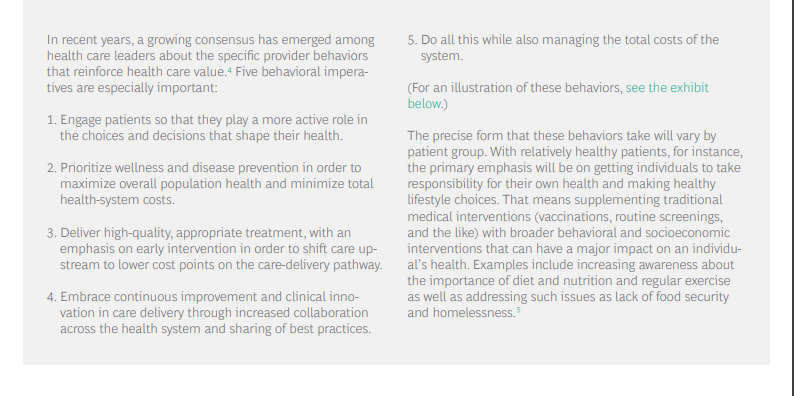

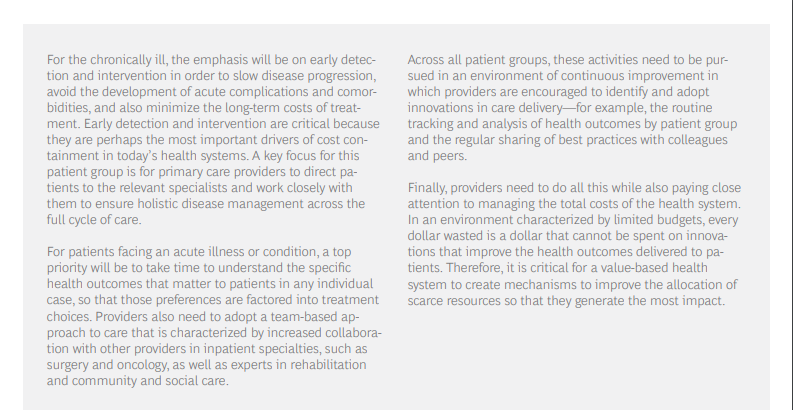

Most health care providers want to do the best for their patients. But, too often, traditional activity-based payment models create disincentives to engage in the kind of clinical behaviors that improve health care value.

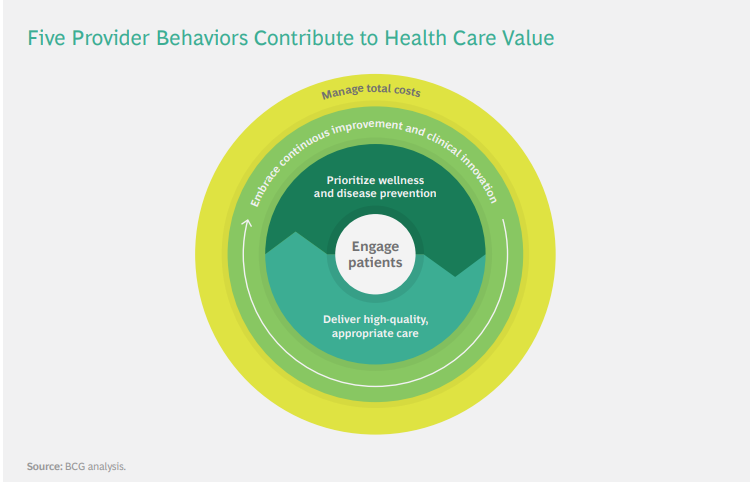

The purpose of value-based payment is to eliminate these obstacles and create financial incentives to encourage provider behaviors that improve the value delivered to patients. (See the sidebar “Five Provider Behaviors That Boost Health Care Value.”)

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

In the past, most health systems have relied on a typical division of labor. Payers were responsible for managing the costs to health systems, while providers were responsible for the quality of care delivered to patients (although often lacking the information to effectively measure it). A core principle of value-based health care is that payers and providers should share accountability for and jointly manage costs and quality.

Payers have a key role to play because they have visibility across health systems and, therefore, are well positioned to monitor outcomes and costs for full cycles of care. However, providers are on the frontline of care delivery making the day-to-day decisions that affect patient care. T

herefore, they are in the best position not only to make informed tradeoffs about how best to deliver quality care in the most cost-effective way but also to innovate clinically to transcend those tradeoffs and deliver the same or better quality at a lower cost. Three value-based payment models help create incentives for providers to achieve these goals:

- Pay-for-performance bonuses,

- bundled payments, and

- population-based payments.

Pay-for-Performance Bonuses

The simplest form of value-based payment is to pay a bonus to providers when they achieve a predetermined performance goal-for example, when they meet a defined threshold for quality care, effectively manage costs, follow clinical guidelines, or track and report health outcomes.

Bonuses can be used to introduce a value-based component to a traditional fee-for-service payment system.

They can be used in combination with other value-based payment models. They can be designed as a pure upside incentive to base compensation in order to limit provider risk, or some portion of that base compensation can be put at risk if providers do not achieve their performance targets.

The early results have been mixed.

ACOs that participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) of the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) typically outperform non-ACO providers on the quality measures tracked by CMS.[8]

And in 2017 (the most recent year for which data is available), 60% of the Medicare ACOs achieved savings relative to their historical benchmarks, with 34% saving enough to trigger shared-savings bonuses.9

However, the total cost savings generated by MSSP since its inception have been quite modest.

In fact, the program did not break even until 2017.

This was because the vast majority of ACO shared-savings contracts (roughly 92%) were established as upside only.

As a result, the total costs to Medicare (the combination of increased spending at ACOs that did not meet their benchmarks and the cost of shared-savings payments to those that did) have, until recently, been greater than the total savings generated.

Of course, this may change as ACOs gain experience at optimizing quality and costs and as CMS transitions ACOs to a two-sided risk model in which providers could lose money if they do not meet predefined cost and quality benchmarks.

The jury is still out as to whether the ACO model, developed in the context of the US health insurance system, is relevant to other national health systems.10

Some other countries have taken a simpler approach to using bonuses to reward providers for effectively managing the quality and total cost of care for their populations.

In Switzerland, for example, provider networks are given a relatively modest performance bonus without assuming financial risk.

This policy has reduced total system costs by 17% while maintaining established quality standards. (See the sidebar “Using a Bonus to Manage Total Cost and Quality: The Swiss General-Practitioner Networks.”)

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Bundled Payments

Another model that health systems are implementing to shift the focus to health care value is to establish a comprehensive fee for a clearly defined episode of care, rather than paying providers for each discrete service delivered in the care cycle.

Known as bundled payments, this model also typically makes a portion of provider compensation conditional on the ultimate health outcomes of patients well after the initial surgery or treatment.

This creates incentives for providers to factor in the downstream effect of their clinical decisions, strive to minimize complications and avoid medically unnecessary care, and make informed tradeoffs (such as whether to recommend expensive hospitalization or cost-effective outpatient care) at various points in the care cycle.

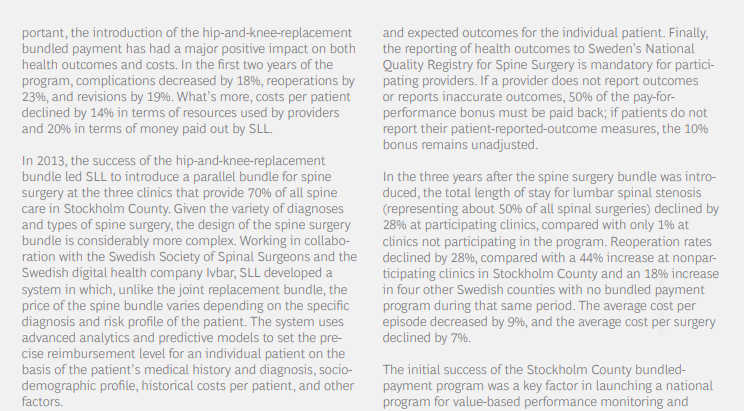

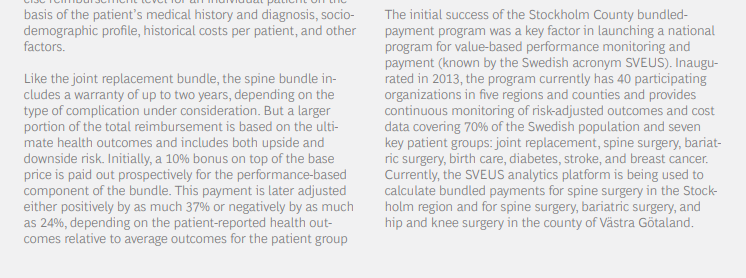

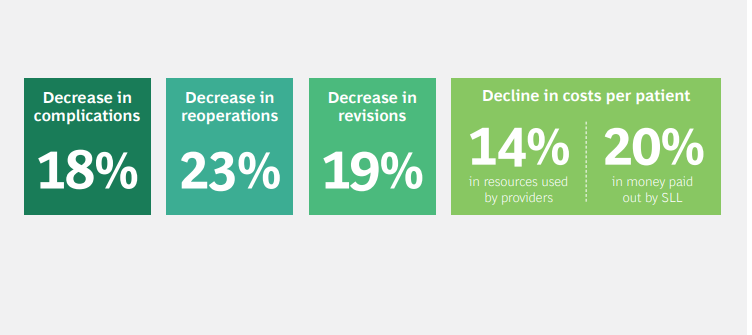

As health systems gain experience with bundled payments, they are developing increasingly sophisticated ways of designing and implementing them and spreading them across the entire health system. In Sweden, for example, a single pilot project that started in the Stockholm metropolitan area has spread to other regions over the past decade and, in some situations, delivered double-digit improvements in both health outcomes and costs. (See the sidebar “Sweden’s Expanding Program of Bundled Payments.”)

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Population-Based Payments

A third value-based payment model pays a predetermined fee to cover all the health needs of each person in a given patient population. The classic example is capitation.

Capitation gives providers a powerful financial incentive to manage total system costs.

In effect, providers take on the financial risk of delivering cost-effective care. To the degree that they can keep costs under the capitated payment, providers benefit financially; to the degree that they cannot, providers suffer losses (although most capitated systems insure providers against extreme outlier cases).

In order to deliver improved health care value, however, capitation must be combined with systematic tracking of health outcomes for specific patient groups or paired with a bonus for delivering high-quality care.

This ensures that cost savings are not achieved through rationing or other practices that come at the expense of patient health outcomes.

Capitation has long been in place (often in combination with other forms of value-based payment models, such as bonuses or bundled payments) at US integrated payer-providers, such as Kaiser Permanente and Intermountain Healthcare, both of which are acknowledged as leaders in value-based health care.11

But implementing capitation is complex, and not every health system or provider group has sufficient capacity, scope, and the necessary managerial capabilities to administer it effectively. Because capitation requires providers to function akin to an insurer and manage financial risk, it works best when providers can manage the risk across a large population of patients. For example, early experiments in using capitation to manage system costs in the UK foundered because of the narrow scope of the initiatives.

Primary care providers assumed risk for the total cost of primary care but without any financial liability for downstream care in specialist or tertiary settings. As a result, capitation did not really function as an effective incentive for managing total system costs.12

Given this complexity, many health systems are experimenting with other ways to focus providers on population-wide quality and costs.

One approach is to use proxies for total population quality and costs, such as the ACO shared-savings program discussed above.

Another is to create targeted capitation payments for specific population groups (for example, healthy newborns or all patients suffering from diabetes).

Capitation is used in New Zealand for primary care, in the UK for mental health, and in the US by Medicare Advantage programs (which are offered to Medicare patients by US private insurers).

The latter have been shown to deliver better health outcomes than traditional fee-for-service Medicare programs at nearly one-third the cost.13

Characteristics of Successful Payment Initiatives

Of the 30 value-based payment initiatives we studied,

- about half reported quantified improvements in both quality and costs,

- a quarter reported improvements but without rigorous assessment, and

- another quarter reported mixed results or no improvement in health care value.

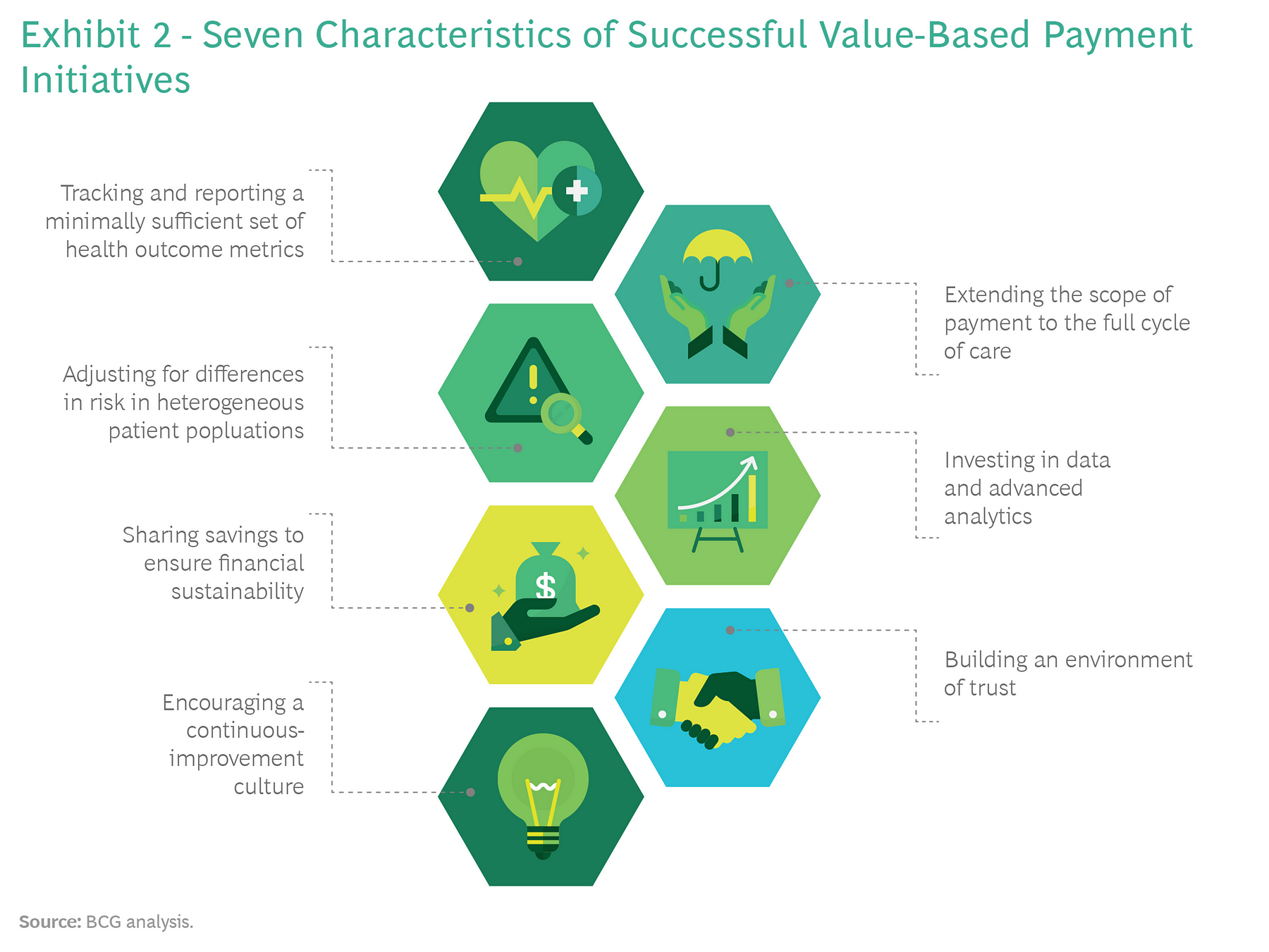

When we looked closely at these case studies, we identified seven characteristics that were common to successful value-based payment initiatives-regardless of the payment model-and that distinguished them from the rest. (See Exhibit 2.)

Tracking and Reporting a Minimally Sufficient Set of Health Outcome Metrics

Value-based health care is all about delivering better health outcomes for the same, or a lower, cost. Therefore, measuring and reporting the health outcomes that matter to patients is a prerequisite for achieving sustainable value-based payment reform. The most successful initiatives that we studied supplement their traditional metrics-such as adherence to process standards and compliance with treatment guidelines-with metrics that reflect the health outcomes delivered to patients. Indeed, some of the most successful initiatives include financial incentives for providers to report outcomes; others mandate reporting outcomes as part of a national health policy.

When tracking health outcomes, it’s important to strike the right balance between too many metrics and too few. Too many, and the metrics will provide weak signals that have minimal impact on provider behavior; too few, and they risk missing relevant outcomes.

Consider the example of prostate cancer. If a health system tracks only long-term mortality (say, five-year survival rates), then the system is likely to miss large variations in outcomes that matter to patients-for instance, whether or not they suffer from incontinence or severe erectile dysfunction a year after surgery. Organizations such as the International Consortium of Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) have made significant progress in defining minimally sufficient sets of the relevant health outcomes for specific diseases and conditions.15 Notes: 15 ICHOM has assembled international working groups of clinicians and patient representatives that have agreed on minimally sufficient standard sets for the relevant outcomes to track 28 common medical conditions. For more information, see www.ichom.org.

Extending the Scope of Payment to the Full Cycle of Care

For many of the initiatives we studied, the effort to improve health care value failed because value-based payments were limited to only a subset of the care required to achieve desired patient outcomes. In such situations, the payment model did not create incentives for providers to innovate across the full chain of care delivery or manage the total cost of care. By contrast, successful initiatives extended the scope of value-based payments to the full cycle of care (for example, expanding payments to include diagnostics, surgery, and physical therapy), so that providers have an incentive to share information, cooperate with one another to redesign care pathways, and provide the highest-quality care in the most cost-effective manner.

Adjusting for Differences in Risk in Heterogeneous Patient Populations

One of the unintended consequences that designers of value-based payment models need to guard against is inadvertantly creating incentives that encourage providers to cherry-pick only the healthiest patients. Effective value-based payment systems include robust risk adjustment in order to account for patient mix, eliminate adverse selection, and set prices that are fair to all providers, including those managing the most complex and expensive-to-treat cases. Although risk adjustment has historically been prohibitively complex, it is now more accurate and easier to implement, given the advances in computing power, the increasing availability of large data sets, and improvements in predictive analytics.

Investing in Data and Advanced Analytics

To meet the growing need for more comprehensive tracking of outcomes and costs, to have value-based payments cover the full cycle of care, and to implement multiple types of payments at scale, successful initiatives develop advanced-analytics platforms. These platforms integrate data from several sources and continuously feed information to all stakeholders on how they are performing on value. Typically, individual providers do not have either the data or the analytics capabilities to develop such systems on their own. In contrast, because payers have visibility across the entire system, they are usually better positioned to develop the data and analytics platform and then provide it as a shared service to providers. Sweden’s SVEUS program, which provides comprehensive and nearly real-time data with sophisticated risk management, is one example of how these analytics platforms are developing.

Sharing Savings to Ensure Financial Sustainability

Another pattern we observed is that, too often, value-based payment models are implemented by payers as a means to reduce costs in the face of immediate budget pressure. Not enough attention is given to the long-term financial sustainability of the programs. Providers may share in the savings in the short term, but those near-term savings then become the justification for budget reductions in subsequent years. When this happens, it is difficult for providers to see a long-term path to success. For example, a chief criticism of the ACO model in the US is that since the cost benchmarks are based on the previous year’s spending, any savings an ACO achieves are immediately factored in to the subsequent year’s benchmark.

An alternative approach was recently announced for the Blue Premier program, a collaboration of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina (the largest payer in the state) and five major provider systems. Blue Premier has built in mechanisms that protect long-term financial sustainability by ensuring that providers are not penalized in subsequent years for cost improvements in previous years.17 Notes: 17 See J.P. Sharp, et al., “ Engineering a Rapid Shift to Value-Based Payment in North Carolina: Goals and Challenges for a Commercial ACO Program,” NEMJ Catalyst, January 23, 2019.

Building an Environment of Trust

In order for value-based payment models to drive changes in clinical practice, they need to be introduced in an environment of trust among providers, payers, and patients. That may sound like a tall order given the long history of adversarial relations between payers and providers due to the misaligned incentives of fee-for-service reimbursement models. Still, health systems can take a number of steps to build that trust and ensure sufficient buy-in for value-based payment reform. For example, payers can make clear that the focus of initiatives is not just cost containment but also improvement in outcomes. And providers should be heavily involved in the design, implementation, and refinement of payment models, including defining outcomes and reviewing performance bonus criteria. Furthermore, shadow budgets can be employed for a predefined period of time before the implementation of a new payment model to gather feedback, optimize the approach to risk adjustment and claims management, and increase confidence in and understanding of the payment model to ensure a smooth transition.

Encouraging a Continuous-Improvement Culture

Finally, successful health systems recognize that implementing value-based payments is not a one-time event. Rather, it is part of an ongoing transformation of clinical practice. The successful implementation of value-based payments benefits from a learning mindset in which organizations commit to experimentation, innovation, and continuous improvement over time. Indeed, in some situations, it may even involve eliminating value-based payments when the norms and practices of a genuinely value-based organizational culture are firmly entrenched. (For an example, see the sidebar “Why Geisinger Got Rid of Its Value-Based Bonus.”)

Building a Value-Based Payment System

Although the specific approach will, of course, vary depending on the starting point and organization of a given health system, we recommend that health system leaders begin building a value-based payment system by focusing on three strategic interventions.

These include creating incentives to:

- Manage the total cost and quality of the health system, which is critical for encouraging providers to prioritize wellness and disease prevention

- Optimize the value of routine specialist care, which are a predictable and relatively high-cost component of any health system, and

- Optimize the value of complex, acute, inpatient care, which is a major source of fixed costs for any health system

Incentives to Optimize the Value of Routine Specialist Care

At any moment in time, a subset of a health system’s patients require specialized care. And in every system, certain episodes of care happenb appropriate referral, treatment, and, when possible, recovery. The best approach is to develop bundled payments that cover all the providers in the care pathway for the given clinical episode and create incentives for a collaborative, team-based approach to care. In developing a system-wide approach to bundled payments, it’s best to begin with situations that meet the following criteria:

- The episode of care has a clear profile or a clinically defined start pointbb patient for joint replacement who would be better served by physical therapy).

- The care pathway has significant variation in outcomes and costs acrossb patients, and established protocols exist for reducing that variation. Therefore, the episode of care is a promising candidate for improved valueb through innovation and process redesign.

- Providers are able to control the setting of care and, therefore, influence the care pathway. Some episodes of care, such as trauma care, may beb sources of high cost and considerable practice and outcome variation, but the wide variety of patient situations where trauma care is required andb care pathway makes trauma a poor candidate for bundled payments.

- The episode of care represents a significant expense to the health system as a whole (to make it worth the investment of time and effort on the part of payers) and significant volume (to make it worth the investment of providers).

In health systems with multiple payers, a key challenge will be to create common definitions for a given episode. Otherwise, providers will have to adapt to multiple bundled-payment models, adding to system complexity. We believe that there is a great deal that health systems can learn from the leaders in the field. Over time, we expect that the bundled payment model will be standardized for specific clinical episodes and patient groups and adopted by health systems around the world.

Incentives to Optimize the Value of Complex, Acute, Inpatient Care

Whether in a metropolitan area, a region, or across an entire nation, any health system has to fund an extensive fixed-cost infrastructure of hospitals and other facilities to deal with complex cases and acute emergency care. Planning for this infrastructure has two main challenges: estimating the likely needs of the patient population and treating patients in the setting that is best both for patient health and system costs.

Typically, the cost of complex and acute inpatient care has been covered through some combination of activity-based payments and block funding, which is determined on the basis of the hospital’s historical capacity, the size of the population it serves, and its specific role in the health system (for example, an academic medical center with special responsibility to train doctors and innovate experimental types of treatment, or a rural hospital with a mission to deliver acute care in underpopulated regions).

These traditional funding approaches have not typically focused on value. Activity-based payments reimburse hospitals for the procedures performed, rewarding for volume. And population-based or role-based block funding has typically been linked to the number of beds in the facility, rather than a true estimate of the health needs of the population that the hospital serves. Further, traditional payment approaches are rarely tied to patient outcomes, and as a result, are ineffective incentives for value-based care. In fact, they can contribute to a system that relies excessively on expensive hospital care and maintains excess capacity.

With careful design, however, block funding can be transformed into a strategic intervention for building a value-based payment system. First, instead of assigning funding levels by facility size, health systems should employ predictive analytics to estimate likely usage levels on the basis of the demographic, disease, and risk profiles of a region’s population. (Safeguards can also be put in place to protect provider budgets against unusually high costs associated with specialized care that is difficult to predict-for example, major trauma.) A forward-looking rather than historical estimate of demand in critical patient populations can be an effective way to manage capacity; plan for scheduling, training, and clinical education; and adjust to new innovations in care delivery.

Second, instead of conceiving of block funding as limited to the hospital setting, health systems should extend the scope of such funding to settings across the entire network of care. Taking this step creates an incentive for providers to direct demand to the most appropriate and cost-effective site of care-for example, outpatient clinics, community-care facilities, or in-home care with remote monitoring. In this approach, regional hospitals function less as the main site of care and more as a hub in a network. And hospital-based specialist providers become, in effect, general contractors who are responsible for finding the most cost-effective and highest-quality site of care across the entire value chain, contracting with outpatient facilities and working with specialists-such as discharge nurses, visiting nurses, and home health aides-to minimize the total cost of care. Block funding is the approach taken, for example, by Kaiser Permanente, to fund its infrastructure of 38 hospitals in ten states. (See the sidebar “Strategic Block Funding at Kaiser Permanente.”)

Some Common System Challenges

As health systems pursue these interventions, they will also face at least three system-wide challenges. The first is defining the necessary linkages among the payment models. The second is developing measurement systems for tracking health outcomes and costs and building the advanced analytics platform necessary both to feed data to providers and use it as a basis for value-based payments. The third is creating systems to manage risk, both in terms of patient mix and providers’ financial exposure.

In the course of a lifetime, patients will have different needs covered by different value-based payment models. Health system leaders will need to design systems for managing these models across different patient populations and different types of providers. These systems will need to be sufficiently comprehensive but not so complex that they become unmanageable. The principal should be to make the system as simple as possible for patients and providers, while managing complexity through back-end IT systems. Critical choices and tradeoffs will also need to be made around issues such as deciding where to focus a health system’s bundled payment initiatives, how to organize provider payments for patients suffering from multiple morbidities, and what kind of data and advanced-analytics platforms and visualization tools will be necessary to provide the insights necessary to drive continuous improvement of patient value.

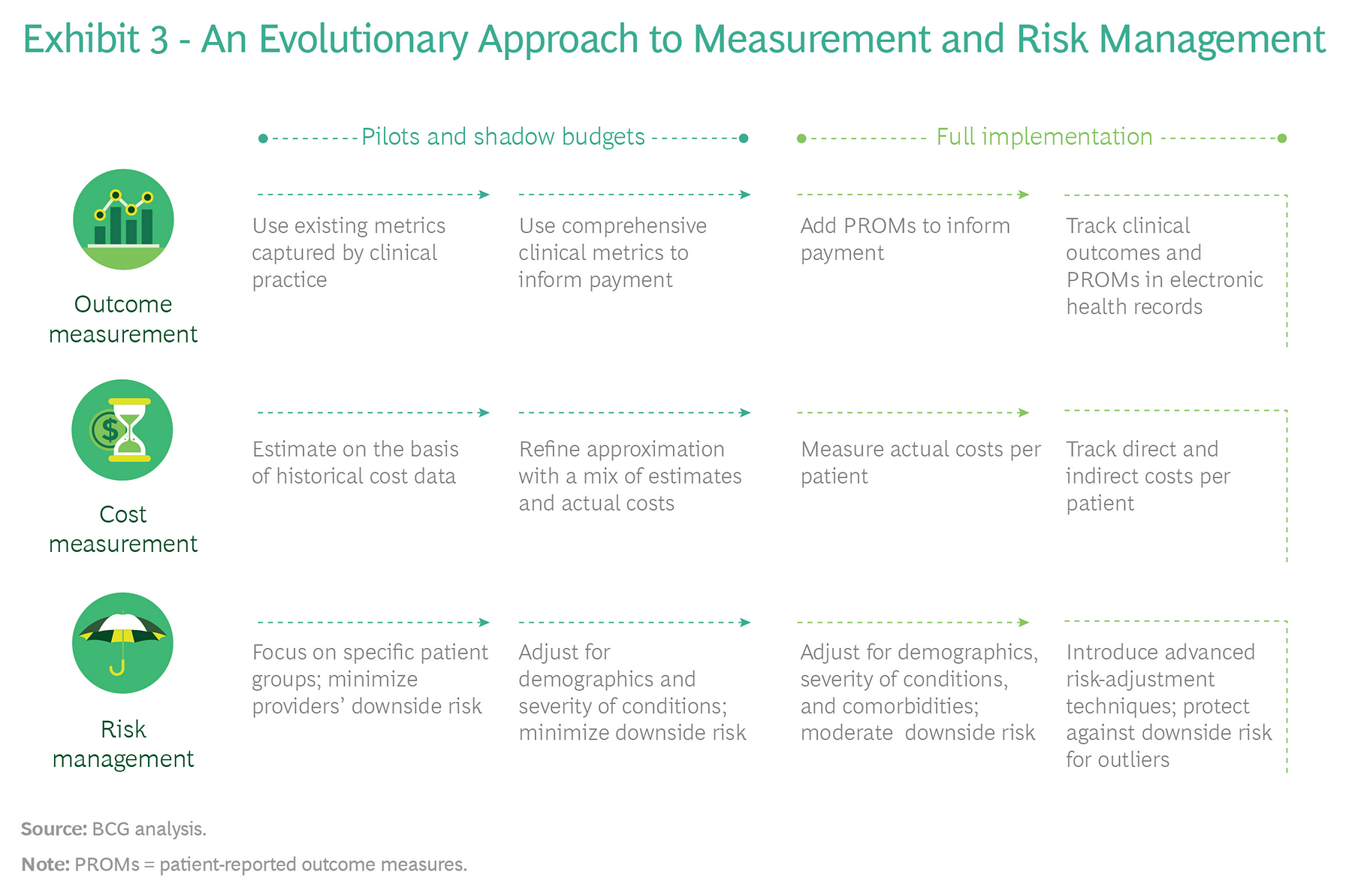

When it comes to measuring outcomes and cost and managing risk, we recommend an evolutionary approach. Health systems don’t have to wait until they have advanced-measurement and risk-adjustment systems in place to get started. Rather, they can begin by using the metrics and methodologies they have, investing in and learning from pilots, and then refining their current systems before implementing payment models system-wide.

For example, to measure health outcomes, start by using existing metrics that are already captured in clinical practice; then, over time, develop advanced information systems in order to routinely capture metrics for both clinical and patient-reported outcomes that are in patients’ electronic health records. To track costs, start with estimates that are based on historical data; then, over time, develop systems that track actual direct and indirect costs per patient. In parallel, start piloting the data and analytics platforms that are necessary to collect the data and share it across the system. To manage risk, initially focus value-based payment models on clearly defined patient groups and exclude downside risk to minimize providers’ financial exposure. Then, over time, gradually introduce more advanced risk-adjustment techniques that allow value-based payment models to be expanded to more complex patient groups (for instance, those with multiple morbidities). And as providers develop the capabilities to manage costs, exclude downside risk only for extreme outlier cases. (See Exhibit 3.)

The appropriate balance between financial and nonfinancial incentives for value-based health care is also likely to evolve over time. In some situations, value-based payments will be the primary catalyst for the long-term reorientation of health systems around value delivered to patients. But as value-based norms and cultures develop in provider organizations, and health systems put in place the analytics to make outcomes and costs transparent, financial incentives may play a less central role.

The point: implementing a value-based payment system is likely to be a dynamic process with considerable experimentation, learning, and adaption. Health system leaders need to be pragmatic and action-oriented. In addition, rather than treat value-based payment in isolation, leaders need to recognize it as one element in a broader set of system-wide changes, designed to align patient, provider, and payer behaviors around the shared goal of improving health care value.

About the authors

Ben Horner, Managing Director & Partner, London

Wouter van Leeuwen, Managing Director & Partner, Amsterdam

Maggie Larkin, Principal, Washington, DC

Julia Baker, Senior Knowledge Analyst, Sydney

About Boston Consulting Group

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders-empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2021. All rights reserved.

Originally published at https://www.bcg.com on January 8, 2021.

To download the PDF open the URL below:

http://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Paying-for-Value-in-Health-Care-September-2019_tcm9-227552.pdf