A pharmacogenomic approach, where genetic variation informs choice of drug and dose, can facilitate greater precision in prescribing and an increasingly personalised approach to drug therapy

This is an excerpt of the long version of the report below (which Executive Summary is reproduced here), focused on “Chapter 1 — Introduction”

Personalised prescribing: using pharmacogenomics to improve patient outcomes

A new report from the Royal College of Physicians and British Pharmacological Society joint working party considers the opportunities provided by increasing pharmacogenomic testing.

Royal College of Physicians

British Pharmacological Society

24 March 2022

Introduction (Chapter 1)

With increasing life expectancy and more people living with multiple long-term conditions, the use of medicines is growing.

In England alone, the NHS dispensed well over 1 billion prescription drugs in 2015, 50% more than in 2005.[1]

There is significant variability in people’s responses to these drugs, and harm can arise from both Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) and lack of efficacy.

In addition to causing adverse patient events, avoidable ADRs are estimated to cost the NHS £530 million annually in hospital admissions.[2]

In addition to causing adverse patient events, avoidable ADRs are estimated to cost the NHS £530 million annually in hospital admissions

There is now evidence that the potential for both ADRs and lack of efficacy for many drugs can be predicted by genetic variation in someone’s genetic profile.

This is also known as ‘polymorphism’, ie different genetic sequences at the same locus.

This genetic variability can be related to both pharmacokinetic (how the body processes the drug) and pharmacodynamic (how the drug affects the body) properties.

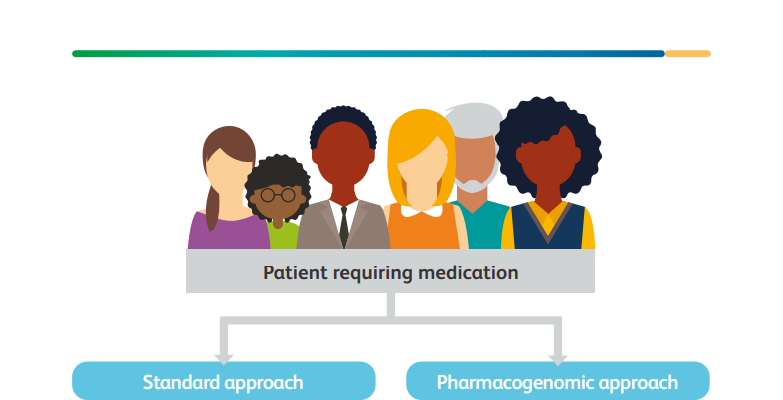

A pharmacogenomic approach, where genetic variation informs choice of drug and dose, can facilitate greater precision in prescribing and an increasingly personalised approach to drug therapy (Fig 1).

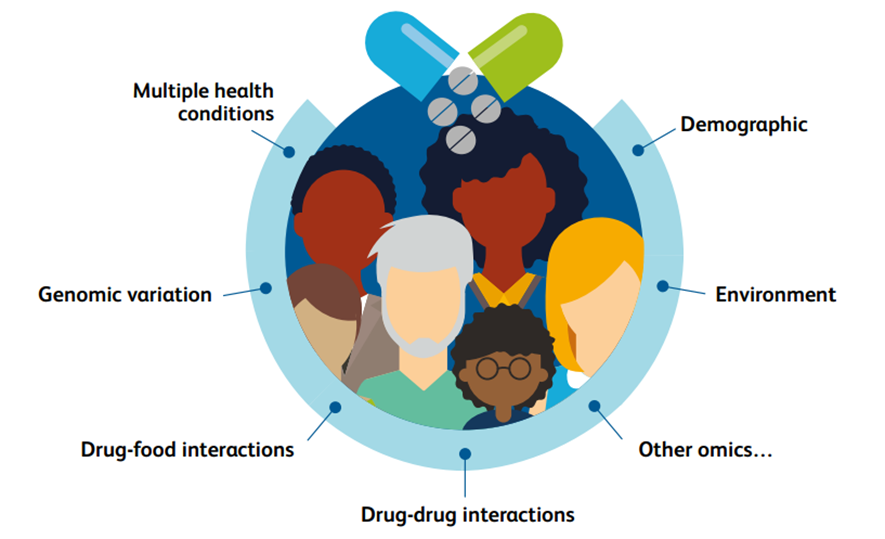

Clinically, it is clear that there is marked interindividual variability in the response to drugs that are taken, affecting their efficacy and toxicity.

This variation is largely attributable to four key factors: demographic, health, exogenous drug and food interactions, and genomic variation.

Fig 1. Interindividual drug response

A pharmacogenomic approach, where genetic variation informs choice of drug and dose, can facilitate greater precision in prescribing and an increasingly personalised approach to drug therapy

It has the potential to improve patient outcomes by increasing the efficacy of medicines and decreasing ADRs.

This is associated with reducing the number of preventable health conditions and deaths, as well as the costs to the NHS.

The UK is at the forefront of a genomic revolution, having first undertaken the 100,000 Genomes Project, which is now aiming to extend to 5 million genomes.

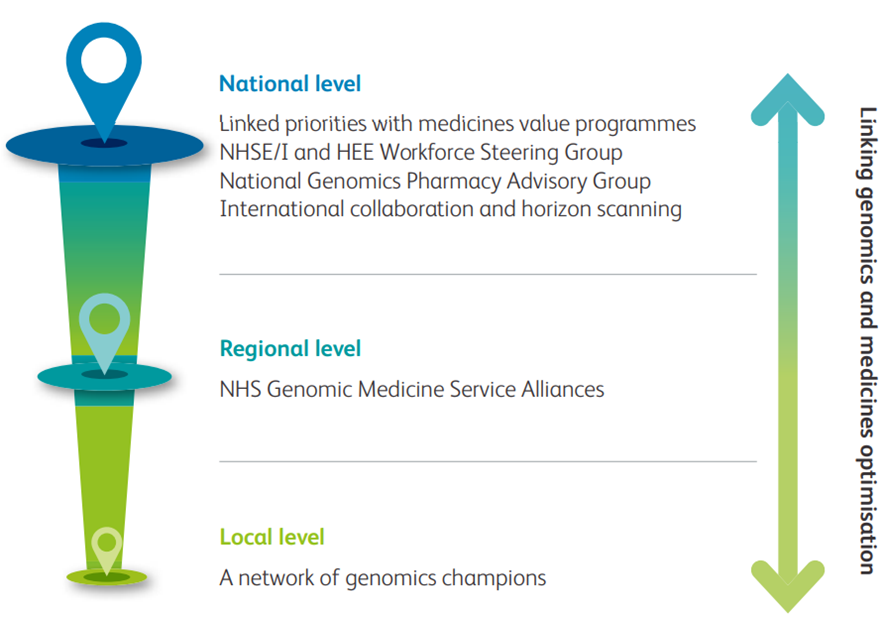

In England, the NHS Genomic Medicine Service (formed in 2018) and NHS Genomic Medicine Service Alliances (formed in 2020) aim to integrate research, education and diagnostic resources to bring pharmacogenomics, as a branch of personalised genomic-targeted medicine, to the bedside (Fig 2).

The UK is at the forefront of a genomic revolution, having first undertaken the 100,000 Genomes Project, which is now aiming to extend to 5 million genomes.

Fig 2. An example of how personalised medicine is being embedded in England

NHSE/I = NHS England and Improvement;

Similar schemes are also present in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Guided by the National Genomic Test Directory, pharmacogenomics-informed prescribing has the potential to be a daily prescribing reality across the UK, and therefore professional body leadership should issue guidance and recommendations to support bedside integration by clinicians.[3]

Guided by the National Genomic Test Directory, pharmacogenomics-informed prescribing has the potential to be a daily prescribing reality across the UK …

To that end, this joint RCP/BPS working party report looks at evidence presented by representatives of a number of physician specialist societies as well as representatives from other royal colleges and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

It aims to summarise the current state and promise of pharmacogenomics within the NHS in the UK and to highlight opportunities for further development.

Representatives were nominated by their respective societies to give evidence on behalf of their specialty body.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Personalised prescribing: using pharmacogenomics to improve patient outcomes

A new report from the Royal College of Physicians and British Pharmacological Society joint working party considers the opportunities provided by increasing pharmacogenomic testing.

Royal College of Physicians

24 March 2022

We all vary in our responses to medicines.

There can be enormous variation from person to person in whether a medicine works, whether it causes serious side effects and what dose is needed.

There can be enormous variation from person to person in whether a medicine works, whether it causes serious side effects and what dose is needed.

This variation can be due to many factors, including an individual’s genes.

Scientists have established a genetic cause for such variation for over 40 medicines.

The study of this area is called pharmacogenomics.

Pharmacogenomic testing can be used to discover which variants of genes an individual carries, and whether they impact on the response to medicines they are given.

This information can be used to guide the choice of medicine and dose, increasing the likelihood that each person receives the most effective medicine for them, at the best dose, the first time they are treated.

Pharmacogenomic testing can be used to discover which variants of genes an individual carries, and whether they impact on the response to medicines they are given.

A new report from the Royal College of Physicians and British Pharmacological Society joint working party considers the opportunities provided by increasing pharmacogenomic testing.

It includes a set of recommendations encompassing steps along the pathway to embedding pharmacogenomics in the NHS.

It covers understanding the evidence for each test, working with patients and the public to understand their needs and communicate potential benefits of testing, training healthcare professionals to exploit advances in pharmacogenomics, working with leaders to commission testing, and ensuring that it is implemented effectively in practice.

A new report from the Royal College of Physicians and British Pharmacological Society joint working party considers the opportunities provided by increasing pharmacogenomic testing.

The report has been endorsed by

- the Association of Cancer Physicians,

- British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology,

- British Society for Genetic Medicine,

- British Society for Haematology,

- British Thoracic Society,

- Clinical Genetics Society,

- Genomics England,

- Royal College of Anaesthetists,

- Royal College of General Practitioners,

- Royal College of Psychiatrists,

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society and the UK Kidney Association.

The ultimate goal is to make pharmacogenomic-based prescribing a reality for all. This will empower healthcare professionals to deliver better, more personalised care, and in turn improve outcomes for patients and reduce costs to the NHS.

Alongside the main report, a summary for patients and the public is also available to download.

Originally published at https://www.rcp.ac.uk on March 24, 2022.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (Executive Summary)

Personalised prescribing — Using pharmacogenomics to improve patient outcomes

A report from the Royal College of Physicians and British Pharmacological Society joint working party

Report of the PGx working party

Citation for this document

Royal College of Physicians and British Pharmacological Society. Personalised prescribing: using pharmacogenomics to improve patient outcomes. Report of a working party. London: RCP and BPS, 2022. Review date: 2026.

Foreword

The NHS is under tremendous pressure: health inequalities are widening, waiting times for hospital treatment are lengthening, access to primary care is becoming more difficult, the stock of ill health in the population is increasing and we are at the limits of affordability.

The model of care that has evolved since the NHS was created in 1948 has to change.

The NHS is under tremendous pressure. The model of care that has evolved since the NHS was created in 1948 has to change.

And by change, I do not mean another reorganisation — enough deckchairs have been moved over the years for us to know that that is not the answer

Part of the answer is revealed in this hugely important document.

In simple terms, our understanding of human biology has been transformed by the sequencing of the human genome and our new-found knowledge of genetic variation.

We have always known that we were different, now we know why.

Part of the answer is revealed in this hugely important document.

In simple terms, our understanding of human biology has been transformed by the sequencing of the human genome and our new-found knowledge of genetic variation.

And we can use that knowledge to predict illness, diagnose illness and to treat illness on an individual, personalised basis.

This will revolutionise medicine and, combined with a digitally driven population health approach, fundamentally change the traditional model of care.

And we can use that knowledge to predict illness, diagnose illness and to treat illness on an individual, personalised basis.

This will revolutionise medicine and, combined with a digitally driven population health approach, fundamentally change the traditional model of care.

But it will not change the fundamental value on which the NHS is based: equality.

Genomic medicine, of which pharmacogenomics is an integral part, must be available to everyone.

It must therefore be funded centrally; it is too important to risk a postcode lottery.

It gives the NHS a chance to reduce health inequality — we must not risk the reverse.

Implementation of pharmacogenomics into the NHS would be the first example in the world of integration into a whole healthcare system, again highlighting the leadership of the UK in genomics.

But it will not change the fundamental value on which the NHS is based: equality.

I remember a time some 5 years ago when Prof Munir Pirmohamed came to see me to talk about the obscure, unknown and overlooked subject of pharmacogenomics, a subject of which I and most others knew little. No longer. It is now mainstream, it is the future, it can now help us to deliver a new, modern personalised healthcare system fit for 2022, not 1948.

Lord David Prior

Chair of NHS England

Executive summary

We all vary in our responses to medicines.

Some people respond very well, while others may not respond at all, and some may develop side effects from their medicines.

At present, we cannot predict how an individual will respond to the first medicine they are prescribed.

This variability in response to medicines can be due to many factors, including an individual’s genes.

There is increasing scientific evidence that natural variation in particular genes influences how well a medicine works for an individual, and whether they will experience side effects.

The study of this area is called pharmacogenomics.

Pharmacogenomic testing can be used to discover which variants of genes an individual carries, and whether they impact on the response to medicines they are given.

This information can be used to guide the choice of medicine and dose, increasing the likelihood that each person receives the most effective medicine for them, at the best dose, the first time they are treated.

Pharmacogenomic testing is already benefiting NHS patients in some special cases.

For example, in breast cancer and colorectal cancer it is used to understand whether someone can safely be prescribed the drug 5-fluorouracil.

Implementing pharmacogenomic testing in daily practice in the NHS has the potential to benefit many more people and improve their care.

Pharmacogenomic testing is already benefiting NHS patients in some special cases.

For example, in breast cancer and colorectal cancer it is used to understand whether someone can safely be prescribed the drug 5-fluorouracil.

However, wider implementation of pharmacogenomic testing in the NHS has been hampered by:

- the need for more research to understand the scientific evidence for testing

- high costs of testing in the past

- poor availability of tests outside specialist settings

- the need to train healthcare professionals in recent advances in pharmacogenomics

- a lack of pharmacogenomic information in the tools used on a daily basis by healthcare professionals, such as electronic healthcare systems.

This guidance, produced by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) and the British Pharmacological Society (BPS) joint working party, considers these barriers as well as the opportunities provided by increasing pharmacogenomic testing.

It includes a set of recommendations encompassing steps along the pathway to embedding pharmacogenomics in the NHS.

It covers understanding the evidence for each test, working with patients and the public to understand their needs and communicate potential benefits of testing, training healthcare professionals to exploit advances in pharmacogenomics, working with leaders to develop the NHS National Genomic Test Directory and commission testing through the relevant pathways in the four nations, and ensuring that testing is implemented effectively in practice.

It is vital that any pharmacogenomics service is adequately funded in all four UK nations, and equally available across NHS regions within each devolved nation.

The ultimate goal is to make pharmacogenomic-based prescribing a reality for all in the UK NHS.

This will empower healthcare professionals to deliver better, more personalised care, and in turn improve outcomes for patients and reduce costs to the NHS.

Although we focus on the UK, many of the issues discussed in the report are also relevant to other global healthcare systems, and learning from each other will be important in optimising medicines use around the world.

The ultimate goal is to make pharmacogenomic-based prescribing a reality for all in the UK NHS.

This will empower healthcare professionals to deliver better, more personalised care, and in turn improve outcomes for patients and reduce costs to the NHS.

Summary for patients and the public

Introduction

People are living longer today than ever before.

But an ageing population means more and more of us are likely to live with long-term health conditions that require medication.

This means the number of medicines we are taking is increasing.

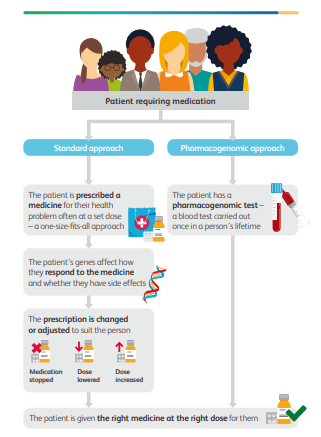

Many currently available medicines are ‘one size fits all’.

This means that people are prescribed a medicine for a particular health problem at a set dose.

But medicines don’t always work in the same way for different people; some people might respond very well to treatment, some might not show any response at all, and for some their medication may also give them unwanted side effects.

We cannot completely predict how someone will respond to the medicine they are prescribed, but there is now good evidence that their genetic information — the information stored in their DNA — plays a key part.

What is pharmacogenomics?

Everyone has different genetic information, stored in the genes they inherited from their parents.

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how genes affect a person’s response to drugs. It brings together the science of drugs (pharmacology) and the study of genes and their functions (genomics) to develop and prescribe medications that are tailored to a person’s genetic makeup.

Scientists have learned a great deal about how inherited differences in your genes can affect your body’s response to medications.

Pharmacogenomic testing can be used to discover which variants of genes you carry, and how they are likely to influence the way your body responds to medicines you might be given.

Because your genes hardly change throughout your lifetime, a pharmacogenomic blood test needs to be done once.

The test results could then be used throughout your life to guide the choice and the dose of medicine, making it more likely that you receive the most effective medicine for you the first time you are treated, and with the fewest potential side effects (see the graphic on page 10).

What do we know so far?

Using a person’s genetic makeup to guide treatment is already a reality for some.

The UK is a world leader in mapping individual genomes (all of a person’s genetic information), and the expertise and technology needed to roll out this approach to treatment more broadly is already well established.

In fact, pharmacogenomic testing is already benefiting NHS patients in some cases.

- For example, in breast and colon cancer, pharmacogenomics is used to understand whether a person can safely be prescribed the chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil.

- Research has also shown that there are genetic differences in the way people respond to the painkiller codeine. Codeine works better for some people than others, while in some it can have more side effects, but we do not routinely test before prescribing codeine.

Using pharmacogenomic testing more widely has the potential to keep people healthier for longer, improving their NHS care and outcomes.

Unwanted side effects from prescription drugs cost the NHS £530 million annually in hospital admissions.

Getting it right the first time could help save the NHS money and resources

Using pharmacogenomic testing more widely has the potential to keep people healthier for longer, improving their NHS care and outcomes.

Unwanted side effects from prescription drugs cost the NHS £530 million annually in hospital admissions.

What is the problem?

Making pharmacogenomics available to everyone is not straightforward.

- The tests are not widely available.

- There has also been a lack of training, and

- there is limited information on pharmacogenomics in the online systems and tools used by prescribers every day, which makes it difficult to roll out more broadly.

What are the next steps?

Together, the Royal College of Physicians and the British Pharmacological Society joint working party on pharmacogenomics have set out a plan to try to overcome these barriers.

The report brings together what healthcare professionals know about pharmacogenomics and makes recommendations for how we can combine research, education and resources to bring this technology to clinics across the UK.

The report brings together what healthcare professionals know about pharmacogenomics and makes recommendations for how we can combine research, education and resources to bring this technology to clinics across the UK.

The recommendations include working with patients and the public to understand their needs.

They also include communicating about the potential benefits of testing, understanding the evidence for each test, training healthcare professionals to make the most of advances in pharmacogenomics, working with NHS leaders to commission testing, and ensuring that testing is implemented effectively and fairly in practice.

Clearly, any genomic data collected by the NHS as part of clinical care must be securely stored and kept confidential in line with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Clearly, any genomic data collected by the NHS as part of clinical care must be securely stored and kept confidential in line with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The ultimate goal is to make pharmacogenomic prescribing a reality for everyone within the NHS. This will empower healthcare professionals to deliver better, more personalised, care.

Recommendations

1.Clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics should occur in both primary and secondary care settings, as well as in specialised centres across the four nations in keeping with the Genome UK commitment.

This should be implemented in a manner that reduces health inequalities, upholds the principles of the NHS, and reflects the wide range of drugs that have actionable pharmacogenomic recommendations available.

Implementation into the NHS is likely to be a gradual and iterative process, which should evolve, steer towards and converge onto a comprehensive service incorporating all the elements outlined in this report.

2.Mainstreaming pharmacogenomic services in the NHS throughout the UK should be commissioned and funded through the relevant pathways in the four nations rather than locally driven to avoid a postcode lottery of care and thereby exacerbate inequalities.

Services should include standards for test turnaround times, flexibility in the type of technology used depending on the gene–drug pair, and standards for reporting, storing and incorporating test results in the electronic healthcare record.

The UK is also a leader in whole genome sequencing, and the number of people who have had their genomes sequenced is increasing all the time.

Pharmacogenomic information contained within these genomes should not be forgotten, but used in a manner that benefits patients.

3.Pharmacogenomic services will need to be agile and able to work at pace to include newly discovered gene–drug pairs into the NHS National Genomic Test Directory, but also refine the list or recommendations of existing gene–drug pairs based on evidence generated.

4.The implementation of pharmacogenomics should be accompanied by a comprehensive education and training package aimed at all sectors of healthcare to improve the skills of the workforce and embed pharmacogenomics into curricula for training the future workforce.

This should include the following:

- An audit to establish a baseline of where pharmacogenomics is present in pre-registration standards and post-registration curricula, and a gap analysis to identify the standards and curricula missing this information.

- The provision of a layered approach to learning so that healthcare professionals can access ‘just-in-time’ information, short courses or formal qualifications, depending on their professional requirements and personal interests.

- Support for clinicians should be provided as pharmacogenomic testing is rolled out.

This should consist of:

- strategic planning of service delivery models to incorporate workforce planning from the outset to ensure that there are enough healthcare professionals to deliver the service.

There should be consideration around expanding and clearly defining the roles of existing staff to incorporate pharmacogenomics and medicines optimisation - a pharmacogenomics consult service should be developed within each integrated care system (ICS) led by a multidisciplinary team comprising clinical pharmacologists, pharmacists and other interested specialists, taking into account guidelines and prescribing information. Given that most of the prescribing occurs in primary care, it is important that GPs and pharmacists are considered an essential component of this multidisciplinary pharmacogenomics service

- work towards developing clinical decision support systems that can be used in all healthcare settings, focused not only on pharmacogenomics, but also on other advances in medicine (including rare disease and tumour genomics, and artificial intelligence), to develop an end-to-end solution

- considering whether currently available resources such as the British National Formulary (BNF) should include information on pharmacogenomics.

- Pharmacogenomic services should be subject to continuous and iterative evaluation — this should include audit and research, together with patient input, to develop a learning health system which allows continual improvement in the service offered to maximise patient benefits.

- Funding for pharmacogenomic research should be made available, not only to identify new gene–drug pairs, but also to refine existing gene–drug pairs, assess the public health benefits of pharmacogenomic implementation, and undertake patient-related work to understand uptake, acceptance, feedback, equity of access, ethical, legal and social issues, and changing perceptions of pharmacogenomics. Pharmaceutical and diagnostic industries, together with the regulators, should be involved in defining the research agenda, and provide funding where appropriate.

- Pharmacogenomics implementation should be accompanied by clear lines of communication with patient representative bodies, the public and the media.

In addition, patients and the public should be actively involved in service design for the NHS to ensure that the service is patient centred.

Members of the working party

- Professor Sir Munir Pirmohamed (co-chair) British Pharmacological Society (BPS)

- Professor Donal O’Donoghue* (co-chair) Royal College of Physicians (RCP)

- Dr Richard Turner (co-secretary) BPS Dr Emma Magavern (co-secretary) BPS

- Deborah Roebuck RCP Patient and Carer Network

- Dr Paul Ross Oncology Professor Bernard Keavney Cardiology

- Professor Claire Shovlin Respiratory medicine

- Dr Joyce Popoola Renal medicine

- Dr Shuaib Nasser Allergy and immunology

- Dr Meriel McEntagart Clinical genetics Sonali Sanghvi NHS England

- Dr Anneke Seller Health Education England

- Dr Michelle Bishop Health Education England

- Professor Sir Mark Caulfield Genomics England Ravi Sharma Royal Pharmaceutical Society

- Dr Imran Rafi Royal College of General Practitioners

- Dr Jude Hayward Royal College of General Practitioners

Names mentioned

Lord David Prior, Chair of NHS England