Nature Medicine

Ani Nalbandian, Kartik Sehgal, …Elaine Y. Wan, et all

22 March 2021

Executive Summary by

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

Health Transformation Institute

continuous transformation

for better health, care, costs and universal health

July 3, 2022

What is the context?

- COVID-19 is now recognized as a multi-organ disease with a broad spectrum of manifestations.

- Similarly to post-acute viral syndromes described in survivors of other virulent coronavirus epidemics, there are increasing reports of persistent and prolonged effects after acute COVID-19.

- Patient advocacy groups, many members of which identify themselves as long haulers, have helped contribute to the recognition of post-acute COVID-19, a syndrome characterized by persistent symptoms and/or delayed or long-term complications beyond 4 weeks from the onset of symptoms.

What is the scope of the paper?

- Here, we provide a comprehensive review of the current literature on post-acute COVID-19, its pathophysiology and its organ-specific sequelae.

- Finally, we discuss relevant considerations for the multidisciplinary care of COVID-19 survivors and propose a framework for the identification of those at high risk for post-acute COVID-19 and their coordinated management through dedicated COVID-19 clinics.

Overview:

- Early reports suggest residual effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, cognitive disturbances, arthralgia and decline in quality of life.

- Cellular damage, a robust innate immune response with inflammatory cytokine production, and a pro-coagulant state induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection may contribute to these sequelae.

- Survivors of previous coronavirus infections, including the SARS epidemic of 2003 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak of 2012, have demonstrated a similar constellation of persistent symptoms, reinforcing concern for clinically significant sequelae of COVID-19

Selected images:

Herein, we summarize the epidemiology and organ-specific sequelae of post-acute COVID-19 and address management considerations for the interdisciplinary comprehensive care of these patients in COVID-19 clinics

The common symptoms observed in post-acute COVID-19 are summarized.

Conclusions and future directions (excerpt)

- Necessary active and future research include the identification and characterization of key clinical, serological, imaging and epidemiologic features of COVID-19 in the acute, subacute and chronic phases of disease, which will help us to better understand the natural history and pathophysiology of this new disease entity (Table 2).

- Moreover, it is clear that care for patients with COVID-19 does not conclude at the time of hospital discharge, and interdisciplinary cooperation is needed for comprehensive care of these patients in the outpatient setting.

- As such, it is crucial for healthcare systems and hospitals to recognize the need to establish dedicated COVID-19 clinics 74, where specialists from multiple disciplines are able to provide integrated care.

- Prioritization of follow-up care may be considered for those at high risk for post-acute COVID-19 …

- Given the global scale of this pandemic, it is apparent that the healthcare needs for patients with sequelae of COVID-19 will continue to increase for the foreseeable future.

- Rising to this challenge will require harnessing of existing outpatient infrastructure, the development of scalable healthcare models and integration across disciplines for improved mental and physical health of survivors of COVID-19 in the long term.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpt)

Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome

Nature Medicine

Ani Nalbandian, Kartik Sehgal, …Elaine Y. Wan, et all

22 March 2021

Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the pathogen responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has resulted in global healthcare crises and strained health resources. As the population of patients recovering from COVID-19 grows, it is paramount to establish an understanding of the healthcare issues surrounding them. COVID-19 is now recognized as a multi-organ disease with a broad spectrum of manifestations. Similarly to post-acute viral syndromes described in survivors of other virulent coronavirus epidemics, there are increasing reports of persistent and prolonged effects after acute COVID-19. Patient advocacy groups, many members of which identify themselves as long haulers, have helped contribute to the recognition of post-acute COVID-19, a syndrome characterized by persistent symptoms and/or delayed or long-term complications beyond 4 weeks from the onset of symptoms. Here, we provide a comprehensive review of the current literature on post-acute COVID-19, its pathophysiology and its organ-specific sequelae. Finally, we discuss relevant considerations for the multidisciplinary care of COVID-19 survivors and propose a framework for the identification of those at high risk for post-acute COVID-19 and their coordinated management through dedicated COVID-19 clinics.

Main

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the pathogen responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has caused morbidity and mortality at an unprecedented scale globally1.

Scientific and clinical evidence is evolving on the subacute and long-term effects of COVID-19, which can affect multiple organ systems2.

- Early reports suggest residual effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, cognitive disturbances, arthralgia and decline in quality of life.

- Cellular damage, a robust innate immune response with inflammatory cytokine production, and a pro-coagulant state induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection may contribute to these sequelae.

- Survivors of previous coronavirus infections, including the SARS epidemic of 2003 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak of 2012, have demonstrated a similar constellation of persistent symptoms, reinforcing concern for clinically significant sequelae of COVID-19 (refs. 9,10,11,12,13,14,15).

Systematic study of sequelae after recovery from acute COVID-19 is needed to develop an evidence-based multidisciplinary team approach for caring for these patients, and to inform research priorities.

A comprehensive understanding of patient care needs beyond the acute phase will help in the development of infrastructure for COVID-19 clinics that will be equipped to provide integrated multispecialty care in the outpatient setting.

While the definition of the post-acute COVID-19 timeline is evolving, it has been suggested to include persistence of symptoms or development of sequelae beyond 3 or 4 weeks from the onset of acute symptoms of COVID-19 (refs. 16,17), as replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 has not been isolated after 3 weeks18.

For the purpose of this review, we defined post-acute COVID-19 as persistent symptoms and/or delayed or long-term complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection beyond 4 weeks from the onset of symptoms (Fig. 1).

Based on recent literature, it is further divided into two categories:

(1) subacute or ongoing symptomatic COVID-19, which includes symptoms and abnormalities present from 4–12 weeks beyond acute COVID-19; and

(2) chronic or post-COVID-19 syndrome, which includes symptoms and abnormalities persisting or present beyond 12 weeks of the onset of acute COVID-19 and not attributable to alternative diagnoses17,19.

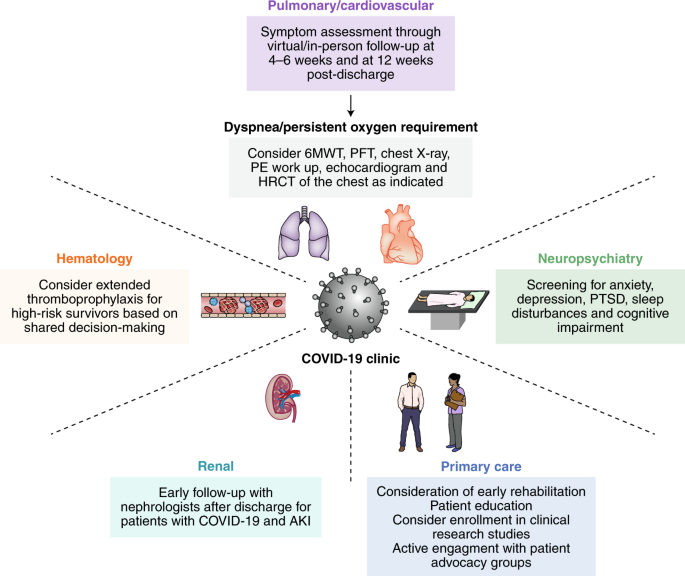

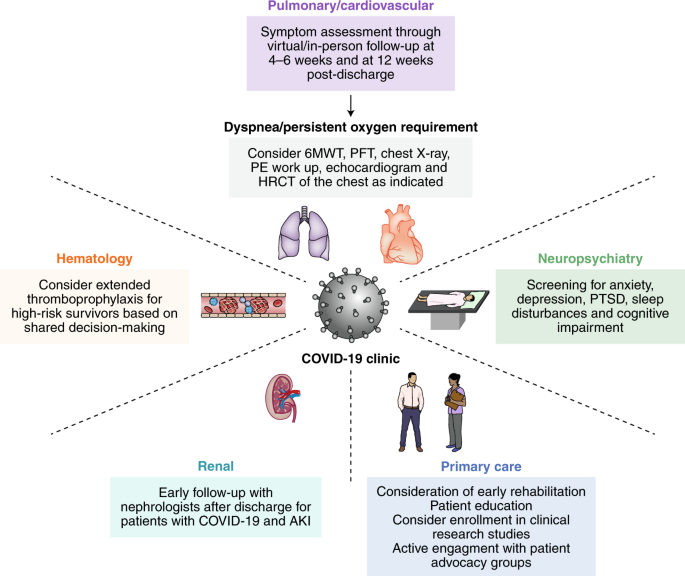

Herein, we summarize the epidemiology and organ-specific sequelae of post-acute COVID-19 and address management considerations for the interdisciplinary comprehensive care of these patients in COVID-19 clinics (Box 1 and Fig. 2).

Acute COVID-19 usually lasts until 4 weeks from the onset of symptoms, beyond which replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 has not been isolated.

Post-acute COVID-19 is defined as persistent symptoms and/or delayed or long-term complications beyond 4 weeks from the onset of symptoms.

The common symptoms observed in post-acute COVID-19 are summarized.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is essential to provide integrated outpatient care to survivors of acute COVID-19 in COVID-19 clinics.

Depending on resources, prioritization may be considered for those at high risk for post-acute COVID-19, defined as those with severe illness during acute COVID-19 and/or requirement for care in an ICU, advanced age and the presence of organ comorbidities (pre-existing respiratory disease, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, chronic cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, post-organ transplant or active cancer).

The pulmonary/cardiovascular management plan was adapted from a guidance document for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia76. HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Box 1 Summary of post-acute COVID-19 by organ system

Pulmonary

- Dyspnea, decreased exercise capacity and hypoxia are commonly persistent symptoms and signs

- Reduced diffusion capacity, restrictive pulmonary physiology, and ground-glass opacities and fibrotic changes on imaging have been noted at follow-up of COVID-19 survivors

- Assessment of progression or recovery of pulmonary disease and function may include home pulse oximetry, 6MWTs, PFTs, high-resolution computed tomography of the chest and computed tomography pulmonary angiogram as clinically appropriate

Hematologic

- Thromboembolic events have been noted to be <5% in post-acute COVID-19 in retrospective studies

- The duration of the hyperinflammatory state induced by infection with SARS-CoV-2 is unknown

- Direct oral anticoagulants and low-molecular-weight heparin may be considered for extended thromboprophylaxis after risk–benefit discussion in patients with predisposing risk factors for immobility, persistently elevated D-dimer levels (greater than twice the upper limit of normal) and other high-risk comorbidities such as cancer

Cardiovascular

- Persistent symptoms may include palpitations, dyspnea and chest pain

- Long-term sequelae may include increased cardiometabolic demand, myocardial fibrosis or scarring (detectable via cardiac MRI), arrhythmias, tachycardia and autonomic dysfunction

- Patients with cardiovascular complications during acute infection or those experiencing persistent cardiac symptoms may be monitored with serial clinical, echocardiogram and electrocardiogram follow-up

Neuropsychiatric

- Persistent abnormalities may include fatigue, myalgia, headache, dysautonomia and cognitive impairment (brain fog)

- Anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances and PTSD have been reported in 30–40% of COVID-19 survivors, similar to survivors of other pathogenic coronaviruses

- The pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric complications is mechanistically diverse and entails immune dysregulation, inflammation, microvascular thrombosis, iatrogenic effects of medications and psychosocial impacts of infection

Renal

- Resolution of AKI during acute COVID-19 occurs in the majority of patients; however, reduced eGFR has been reported at 6 months follow-up

- COVAN may be the predominant pattern of renal injury in individuals of African descent

- COVID-19 survivors with persistent impaired renal function may benefit from early and close follow-up in AKI survivor clinics

Endocrine

- Endocrine sequelae may include new or worsening control of existing diabetes mellitus, subacute thyroiditis and bone demineralization

- Patients with newly diagnosed diabetes in the absence of traditional risk factors for type 2 diabetes, suspected hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression or hyperthyroidism should undergo the appropriate laboratory testing and should be referred to endocrinology

Gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary

- Prolonged viral fecal shedding can occur in COVID-19 even after negative nasopharyngeal swab testing

- COVID-19 has the potential to alter the gut microbiome, including enrichment of opportunistic organisms and depletion of beneficial commensals

Dermatologic

- Hair loss is the predominant symptom and has been reported in approximately 20% of COVID-19 survivors

MIS-C

- Diagnostic criteria: <21 years old with fever, elevated inflammatory markers, multiple organ dysfunction, current or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection and exclusion of other plausible diagnoses

- Typically affects children >7 years and disproportionately of African, Afro-Caribbean or Hispanic origin

- Cardiovascular (coronary artery aneurysm) and neurologic (headache, encephalopathy, stroke and seizure) complications can occur

Epidemiology and additional information

See the original publication.

Conclusions and future directions

The multi-organ sequelae of COVID-19 beyond the acute phase of infection are increasingly being appreciated as data and clinical experience in this timeframe accrue.

Necessary active and future research include the identification and characterization of key clinical, serological, imaging and epidemiologic features of COVID-19 in the acute, subacute and chronic phases of disease, which will help us to better understand the natural history and pathophysiology of this new disease entity (Table 2).

Active and future clinical studies, including prospective cohorts and clinical trials, along with frequent review of emerging evidence by working groups and task forces, are paramount to developing a robust knowledge database and informing clinical practice in this area.

Currently, healthcare professionals caring for survivors of acute COVID-19 have the key role of recognizing, carefully documenting, investigating and managing ongoing or new symptoms, as well as following up organ-specific complications that developed during acute illness.

It is also imperative that clinicians provide information in accessible formats, including clinical studies available for participation and additional resources such as patient advocacy and support groups.

Moreover, it is clear that care for patients with COVID-19 does not conclude at the time of hospital discharge, and interdisciplinary cooperation is needed for comprehensive care of these patients in the outpatient setting.

As such, it is crucial for healthcare systems and hospitals to recognize the need to establish dedicated COVID-19 clinics 74, where specialists from multiple disciplines are able to provide integrated care.

Prioritization of follow-up care may be considered for those at high risk for post-acute COVID-19, including those who had severe illness during acute COVID-19 and/or required care in an ICU, those most susceptible to complications (for example, the elderly, those with multiple organ comorbidities, those post-transplant and those with an active cancer history) and those with the highest burden of persistent symptoms.

Given the global scale of this pandemic, it is apparent that the healthcare needs for patients with sequelae of COVID-19 will continue to increase for the foreseeable future.

Rising to this challenge will require harnessing of existing outpatient infrastructure, the development of scalable healthcare models and integration across disciplines for improved mental and physical health of survivors of COVID-19 in the long term.

Cite this article

Nalbandian, A., Sehgal, K., Gupta, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 27, 601–615 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z

Originally published at https://www.nature.com on March 22, 2021.

About the authors & affiliations

Ani Nalbandian 1,24, Kartik Sehgal 2,3,4,24 , Aakriti Gupta 1,5,6, Mahesh V. Madhavan 1,5, Claire McGroder 7 , Jacob S. Stevens8, Joshua R. Cook 9 , Anna S. Nordvig 10, Daniel Shalev11, Tejasav S. Sehrawat 12, Neha Ahluwalia13, Behnood Bikdeli4,5,6,14, Donald Dietz15, Caroline Der-Nigoghossian16, Nadia Liyanage-Don17, Gregg F. Rosner1 , Elana J. Bernstein 18, Sumit Mohan 8, Akinpelumi A. Beckley19, David S. Seres20, Toni K. Choueiri 2,3,4, Nir Uriel1 , John C. Ausiello9 , Domenico Accili9 , Daniel E. Freedberg21, Matthew Baldwin 7 , Allan Schwartz1 , Daniel Brodie 7 , Christine Kim Garcia7 , Mitchell S. V. Elkind 10,22, Jean M. Connors4,23, John P. Bilezikian9 , Donald W. Landry8 and Elaine Y. Wan 1

1 Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA.

2 Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

3 Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 4Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 5 Clinical Trials Center, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, New York, USA. 6Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale New Haven Hospital, New Haven, Connecticut, USA. 7 Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 8Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 9Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 10Department of Neurology, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 11Department of Psychiatry, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York, USA. 12Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA. 13Division of Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, USA. 14Cardiovascular Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 15Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 16Clinical Pharmacy, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 17Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 18Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 19Department of Rehabilitation and Regenerative Medicine, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 20Institute of Human Nutrition and Division of Preventive Medicine and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 21Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. 22Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA. 23Division of Hematology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 24These authors contributed equally: Ani Nalbandian,

References and additional information

See the original publication