Euro Health

By: Naomi Limaro Nathan, Natasha Azzopardi Muscat, John Middleton, Walter Ricciardi and Govin Permanand

2021, Vol.7, n.1

Summary:

- The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasised that calls for clearer mandates and leadership from health authorities has gone unheard for decades.

- Preventable occurrences in response to the pandemic depict that countries in the WHO European Region suffer from various issues that undermine public health leadership — a necessary capacity to navigate extraordinary times, such as these.

- What remains clear is that there is a dire need for public health to be reinforced and enabled to ensure effective public health responses.

- Furthermore, internal siloes within the field must be broken down and collaboration within and across sectors nurtured, to help build up resilience to handle future emergencies.

Keywords: Governance, Leadership, Public Health, COVID-19, Resilience

LONG VERSION

Introduction — Leadership trends in public health over the past decades

In 1998, the influential United States’ (US) Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a seminal report entitled ‘The Future of Public Health’.[1]

Based on the findings of an expert commission tasked with looking at the state of public health organisation and delivery in the United States at the time, the report set out a conceptual framework for the ‘core functions of public health’, defining public health as “what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions for people to be healthy”.

The IOM report stressed the need for public health bodies at all levels to be strengthened and, crucially, to work closely together.

While referring to municipal, state and federal bodies in the US, this broader appeal for a collective approach to improving health — a clear vision of what public health is and the importance of a coherent approach to counter “continuing and emerging threats to the health of the public” — has been used to orient the public health community globally.

The IOM report’s vision demanded a rethinking of not just what and how services were delivered, but more importantly, the need for clearer mandates and leadership from health authorities.

Published 20 years after the IOM report, a 2018 review by the World Health Organization (WHO) of how public health is organised, financed and delivered in Europe suggests this call was not heeded.[2]

The authors conclude that public health in the region remains fragmented and uncoordinated, delivery structures are not in line with population health goals, services are underfinanced, and that there has been a failure of leadership in many countries.

This was the analysis of the state of public health in Europe a year before SARS-CoV-2 emerged and unleashed a global pandemic.

The IOM report’s vision demanded a rethinking of not just what and how services were delivered, but more importantly, the need for clearer mandates and leadership from health authorities.

(20 years later) … the authors (@ who) conclude that public health in the region remains fragmented and uncoordinated, delivery structures are not in line with population health goals, services are underfinanced, and that there has been a failure of leadership in many countries.

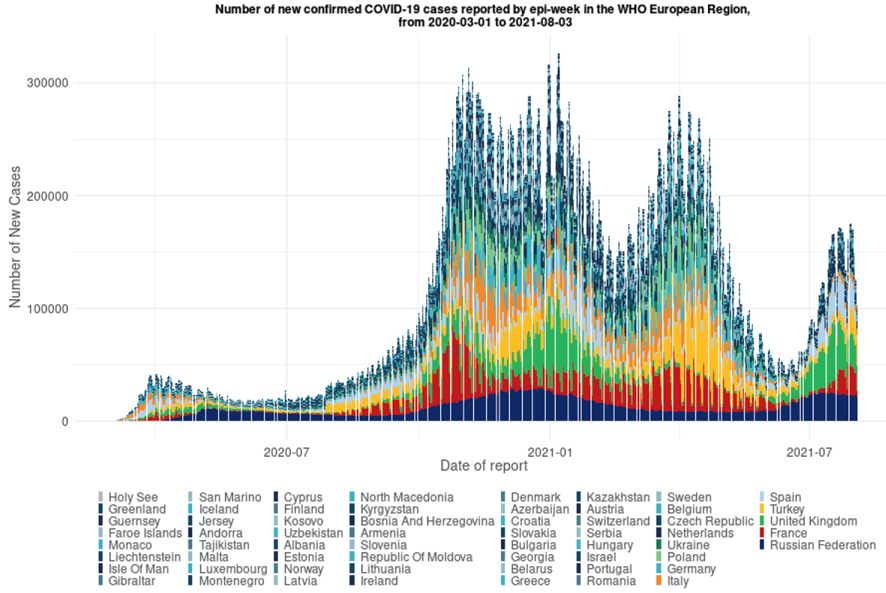

Figure 1: COVID-19 cumulative cases in countries of the WHO European Region across time — July 2021

Source: WHO Regional Office for Europe, Health Emergencies Programme (WHE)

Note: *Turkmenistan is the only country in the Region that has not yet officially reported any cases of COVID-19; comparability is greatly hindered by the huge variance in testing capacity and eligibility between countries.

This article explores health leadership around the COVID-19 pandemic in the WHO European Region, and elicits reasons as to why leadership has not been as effective as expected.

It necessarily deals in generalisations given different health systems, political structures, and relationships between society and decision-makers; both in health and beyond. We note the politicisation of COVID-19, complications related to politicians not being up to the task and putting their interests first, however, our focus is on where the public health community might have done better.

As the pandemic is very much on-going at the time of writing, offering any definitive lessons learned is somewhat premature.

But we can see that certain things were eminently preventable, and these in turn point at potential solutions going forwards.

Public health leadership — a pre-requisite for successful pandemic response

In their 21 May 2021 joint statement on the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Public Health Association (EUPHA) and Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER), noted: “The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the importance of public health leadership.

Countries that had strong public health leadership were better able to design and implement rapid and effective responses that reduced the spread of infection, minimised the impact on lives and the economy, and engaged with the public”.[3]

Case numbers in much of the WHO European Region were dropping at the time and vaccination rates were rising.

A number of countries had therefore begun relaxing public health and social measures (PHSM) and there was a push to allow the hospitality and tourism industries in particular to resume their activities, supported by the use of COVID-19 ‘passports’ to enable international travel.

The focus of many was on the 2021 summer holidays. Since then, however, the emergence and exponential spread of the B.1.617.2 mutation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (known as the Delta variant), has contributed to rising numbers of cases (see Figure 1), increasing hospitalisations and growing numbers of persons suffering from ‘Long Covid’, including children[4] in most countries in the Region, despite increasing numbers of vaccinated individuals.

In some countries, where PHSM were relaxed, we are seeing a re-imposition of these mandates,[5] and even high-level governmental apologies for releasing measures too soon.[6] What does this say about Europe’s ongoing response to the crisis, and about public health leadership specifically?

… the European Public Health Association (EUPHA) and Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER), noted: “The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the importance of public health leadership.

Resounding legacy issues and the politicisation of COVID-19 responses

As COVID-19 grew from a public health issue to a wider societal and economic disaster, the question of ‘Who is in charge?’ became a contested one.

It was clear from the outset that, despite scientists and experts in many countries expressing grave concerns about this pathogen and its likely spread, policymakers often did not listen nor take evidence-based decisions. This ought not be surprising. E

xpertise and science can inform policy, and indeed should, but it is one of many inputs political decision-makers must weigh.

The question, rather, is why this expertise appears not to have been given sufficient weight in the face of a clear public health emergency

“a failure of leadership in many countries”

One answer relates to the diminishing roles of ‘science’ and fact-based approaches versus opinion in much of public discourse today.

As we see in the context of COVID-19, this has knock-on effects in terms of politicians having influence over scientific recommendations as a means of serving their electorates.[7]

Those countries which — at least initially — responded well to the emerging pandemic were ones in which political leaders engaged with the science and prioritised the threat to health over other issues.

In others, the scientific and public health side was given less priority than, for instance, the economy — a false dichotomy as many have pointed out. A more important answer, therefore, concerns legacy.

Recalling the chronic underfunding and fragmentation of public health raised earlier, this has resulted in a loss of authority and voice of the public health community.

Worse yet, it has resulted in weakened ability and capacity of the workforce, especially in the face of a health emergency.

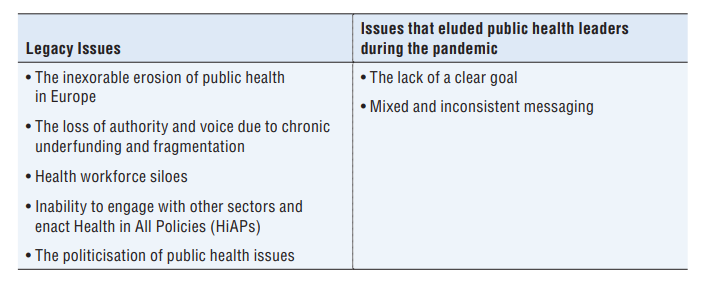

Table 1: Issues undermining public health leadership

Across many countries in the European Region, we have witnessed failures in surveillance, testing and contact tracing.

These are bedrock public health functions which in some instances were entrusted to agencies other than public health.

Moreover, perceived public health failures can have knock-on effects.

A recent study in the United Kingdom (UK) has pointed to higher rates of vaccine hesitancy in areas where the National Health Service was struggling to manage cases early in the pandemic.[8]

The UK went so far as to re-structure its public health agency entirely, ostensibly on the basis of poor performance.[9]

Although clearly a high-level political decision — opposed both within and outside the health arena — the fact the government could dismantle the national public health authority in the midst of the pandemic demonstrates the influence that non-health sector policymakers have over the health sector.

While it is easy to point to political decision-makers as being to ‘blame’ for not ensuring appropriate and up-to-date pandemic plans were in place, and for politicising the pandemic often for their own political gain (see the later article by Greer et al. in this issue for more on the politics of credit and blame), it is also the case that in a number of areas we — in the public health community — have not delivered as expected.

Some of these shortcomings too can be attributed to legacy issues (see Table 1), but others require a bit more introspection if we are to ensure that we can move forward in a solid, more effective and trusted manner.

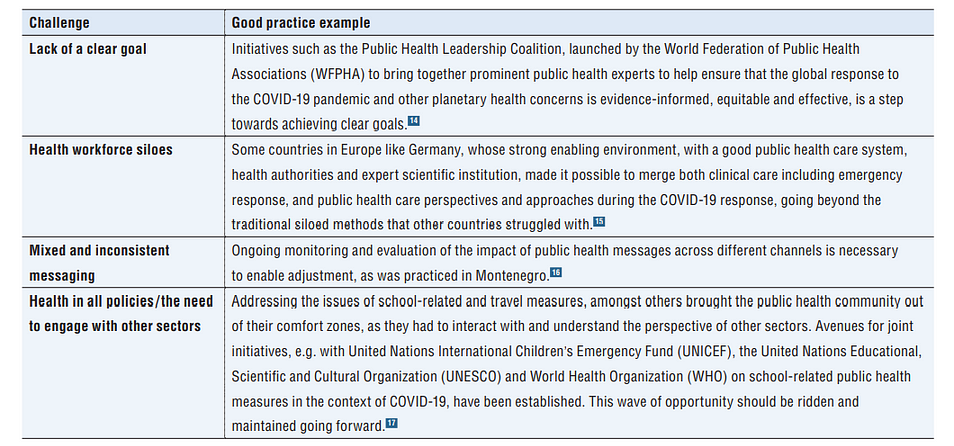

Table 2: Tackling issues undermining public health leadership

Lack of a clear goal

Looking at strategies for tackling the virus across the European Region, as well as the protracted discussions on what strategy to adopt even within individual countries, one could conclude that the public health community (nationally and internationally) failed to agree upon and espouse a clear goal.

Various narratives were given. Initially, the risk from the virus was deemed low, then the aim became to limit transmission between individuals. With the pandemic underway, the goal was then to ‘flatten the curve’ — this referred to slowing the transmission of the virus, ostensibly to spread out hospitalisations rather than reduce overall cases. Thereafter, interest was in protecting the vulnerable, and the goal varied between containment and suppression (with degrees up to ‘maximum’), while the concept of ‘zero-Covid’ was even considered. The actions in many countries now belies an implicit assumption that the goal today is simply learning to live with the virus.

But these narratives are not representative of a clear and consistent public health goal at any stage.

Unlike other public health crises, e.g. HIV where clear targets have been adopted, the concept of sustained control of COVID-19 has not yet been sufficiently pursued nor effectively communicated by the public health community through a series of evidence-informed agreed targets.

Yet, public health professionals understand that risk is not just about the immediate future, but the longer-term. Moreover, early in the outbreak, epidemiologists were already aware of just how transmissible the virus was and warned of many deaths. Minimising the number of deaths from COVID-19 was, however, not articulated as an overarching public health goal in most countries. Instead, it was couched in messages of reassurance, both towards the public and society at large. Further, those who sought to point at predictions and forecasts — the backbone of epidemiology and public health — were often willfully ignored.

“a clear need for a series of common goals to be swiftly agreed”

Evidently, the result of this lack of clarity was seen when hospital care led the early health response in most countries.

This reflects a reactionary rather than proactive view of public health, and one that is clearly not sustainable. Hospital reform has been on the agenda across Europe for decades — bigger hospitals, specialist hospitals, regional hospitals, hospitals which offer integrated health services etc. — and most health sector investment has gone to hospitals rather than primary care. It can, therefore, be legitimately argued that, to some extent, this too is a legacy issue. In the absence of public health leadership and the lack of a clear goal across Europe, a hospital-led response was a necessary consequence rather than an informed choice.

Obviously, goals and their enabling strategies need to be flexible and adapt as evidence emerges, as the issue of droplet versus airborne transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the use of facemasks has shown.

It should also be acknowledged that at any stage of the pandemic, the direction of travel was not fully understood, even by those involved in the response — whether front line health workers, hospital support staff, educators, employers and even the public at large, given their own personal responsibilities towards protecting themselves and others. Without a clear statement of intent around a unifying goal, the response will most likely be trepidatious, also allowing for a political rather than evidence-driven response. There is a clear need for a series of common goals to be swiftly agreed, even if such goals need to be couched in the contextual reality that different countries are at very different stages with health system capacity, testing capacity, and even being able to protect their population through vaccination. This may necessitate a scenario driven, staged approach that countries can strive and work towards, rooted in both epidemiology and behavioural science.

Mixed and inconsistent messaging

An important corollary is that messaging — communication, especially towards the public — is a core function of public health.

This too has been patchy within and across European countries.[10] Obviously in the context of a fast-moving pandemic, the science can be uncertain, and the evidence base not definitive. But transparency and clarity in messaging, and specifically about the uncertainties and risks, is crucial to engender public trust. Balancing good news with the bad helps to promote hope rather than fear, and it is important to include context that connects the news to people’s concerns and prior experiences; “the ‘so what’ of the message has to feel relevant”.[11] In addition to causing confusion and undermining public trust domestically, mixed messaging around key issues — such as European countries’ changing positions on the Astra-Zeneca vaccine — can have global consequences as well.[12] Whilst it is difficult to ensure clear messaging when the overall goal itself has not been clearly set out or has been politicised, attention to clear and consistent messaging is tremendously important when the goals have been set as otherwise the whole objective risks being undermined.

Health workforce siloes

The need for a clear goal has wider relevance for the health workforce.

This is the time for health workers to become united around a singular vision of public health — one in which they can identify their contribution and understand their roles, and especially so in the context of a health emergency. Nonetheless, one feature of the COVID-19 response across many countries has been the division between clinical care including emergency response, and public health care. For the former, identifying cases, undertaking testing and providing life-saving treatments (hospital care) have been crucial to the response. For the latter, mitigating spread of the disease through surveillance, education and community outreach, as well as undertaking contact-tracing and setting out behavioural guidance have been equally crucial. Some countries have been better at merging these perspectives and approaches, while others remained inflexible and have struggled. The role of the public health community in protecting the clinical front liners by advocating for appropriate measures based on data science is critically important in bringing a common purpose round which the entire health workforce can rally.

In recognition of the tremendous effort made by health workers, WHO declared 2021 ‘The Year of the Health and Care Workers’.[13]

During the initial ‘waves’ in Europe when hospitals were becoming overwhelmed and routine services were being delayed or cancelled, health professionals sought to overcome professional boundaries. Hospitals developed differential care pathways, intensive care and nursing teams re-organised themselves, personal protection equipment was rationed, and shared, primary health care professionals provided remote services and specialists were repurposed as part of the surge response (see the later article by Buchan et al., for more on governing the health workforce during the pandemic). The public health workforce has been far less visible in this campaign even though individual public health practitioners have borne as much of the brunt as clinical front liners.

This is, at least in part, also a legacy issue. Across Europe, public health, as a profession, continues to be under-valued and under-resourced in the context of growing demand.

Medicine, particularly specialisation, and the private sector, continue to offer better remuneration, opportunities for advancement and higher levels of reported job satisfaction. In many countries there are so-called ‘medical deserts’ where even basic public health services are absent. Rather than sharing an identity around a singular public health vision, most health professionals see themselves as contributing to a broader understanding of public health through their particular area of focus; that is, as a part of the whole rather than being a “microcosm” of that whole. Notwithstanding the rise of chronic diseases, which show the public health — medicine divide to be an outdated if not somewhat artificial one, the pandemic has pressed home just how fundamental a more integrated understanding of public health is.

Health in All Policies and the need to engage with other sectors

One of the impediments to a coherent health response and good governance in the face of the pandemic has been the lack of joined-up thinking.

We know that public health is about the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organised efforts of society. We understand that this requires a holistic view of health. So too are we aware of the need to ensure heath in all policies, which in turn demand whole-of-government and all-of-society approaches. But our failure to implement this as a matter of course has contributed to the number of infections and deaths given that COVID-19 is especially severe for those with underlying health conditions and those who are disadvantaged societally. With a more coherent and inclusive practice of public health, would the impact of the disease have been so severe?

Interconnectedness of the social, commercial, environmental, and economic determinants of health

As a public health community, we have traditionally not done well in reaching out to other sectors; ensuring Health in All Policies, despite progress and a growing evidence-base, remains under-developed.

COVID-19 has revealed the interconnectedness of the social, commercial, environmental, and economic determinants of health. It thus implores us to expand the scope of public health and to work more closely with sectors such as food, housing, transport, employment and the environment, and to engage with individual actors and entities we would not traditionally see as directly involved in the practice of public health, e.g. trade-unions, supermarkets, employers groups and business etc. Good health leadership will ensure other sectors are involved as partners in the public health system, rather than the relationship being unidirectional — us reaching out to them, or vice versa. It is obvious that a healthier population is going to be more resilient, especially towards any disease that targets those in poorer health or who are at most risk of contracting it.

Table 2 provides some examples of international and country efforts to enable public health leadership by addressing specific challenges (see above)

Going forward

We know from previous health emergencies that it is key to be ‘ahead of the game’; to be able to predict and plan for likely outcomes, to develop scenarios and be prepared to act swiftly, and to ensure that medical and public health systems are fit-for-purpose.

Already on 13 March 2020, Dr Mike Ryan, Director of the WHO’s Global Health Emergencies Programme, said “… you need to be coordinated, you need to be coherent, you need to look at the other sectoral impacts”.[18]

It has been over 18 months since his words made global headlines.

He was warning both the public health community and politicians against inaction in the face of a deadly pathogen, noting further that “If you need to be right before you move, you will never win”.[19]

We now have considerable evidence around strategies and specific measures that work to limit transmission of the virus, and how this can help avoid restrictive PHSM in countries.

Crucially, we now also have highly effective vaccines. And yet cases continue to rise in many countries, messaging remains unclear and some countries are engaged in stop-start PHSM strategies.

Box 1: Towards a reinforced public health in Europe — Key messages

Written almost 25 years ago, the IOM report expressed grave concern over the fact that: “… public health in the United States has been taken for granted, many public health issues have become inappropriately politicised, and public health responsibilities have become so fragmented that deliberate action is often difficult if not impossible”.[20]

In looking at contemporary European responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, substitute ‘Europe’ in place of ‘United States’, or indeed any single European country, and it seems the reasons behind Europe’s poor response and the solutions to them are encapsulated in that sentence.

The public health community has been advocating for the need to strengthen public health institutions and break down silos for decades. This is crucial for protecting and promoting the health of our populations (see Box 1).

It has been suggested that: “COVID-19 is our teacher, giving a heads-up to bigger storms ahead: new epidemics, health backlogs, economic strain, and the health consequences of the climate crisis.

These will dwarf our present problems”.[21]

Perhaps COVID-19 will, finally, be the catalyst for the necessary public health leadership to see this through.

References

See the original publication

About the authors

Naomi Limaro Nathan is Technical Officer,

Natasha Azzopardi Muscat is Director,

Govin Permanand is Senior Health Policy Analyst, Division of Country Health Policies and Systems, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark;

John Middleton is President of the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER), Brussels, Belgium;

Walter Ricciardi is Professor of Hygiene and Public Health at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy.

Cite this as: Eurohealth 2021; 27(1).

Cite this as: Eurohealth 2021; 27(1).

Originally published at

COVID-19 and the opportunity to strengthen health system governance (Eurohealth) (who.int)