This is a republication of the article below, with the title above.

Booster shots are the best defense against Omicron. But a rush on extra jabs may make it harder to stop the rise of new variants

Forbes

GRADY MCGREGOR AND SOPHIE MELLOR

December 20, 2021 8:25 AM GMT-3

verywellhealth

The quick spread of the Omicron variant has sown panic in governments and stunned scientists already overwhelmed by the unrelenting adaptations of the virus behind COVID-19.

Omicron’s growth appears “beyond exponential,” says Michael Toole, an epidemiologist at Burnet Institute in Australia, about the variant’s rise in South Africa, the U.S., and across Europe.

Now, as scientists race to gauge the threat Omicron poses, government officials, public health experts, and medical professionals are increasingly emphasizing the need for vaccinated individuals to get booster shots — currently the best protection against severe disease and death for those infected by the new variant.

The unvaccinated “are looking at a winter of severe illness and death,” U.S. President Joe Biden said in a press briefing on Thursday about the rise of Omicron. “But there’s good news: If you’re vaccinated and you had your booster shot, you’re protected from severe illness and death — period.”

The emphasis on booster shots has already prompted countries like Israel and Singapore to change their definitions of being fully vaccinated to include the booster doses. Other countries, meanwhile, are considering implementing similar rules.

But the emerging consensus on the need for booster shots brings with it another set of dangers.

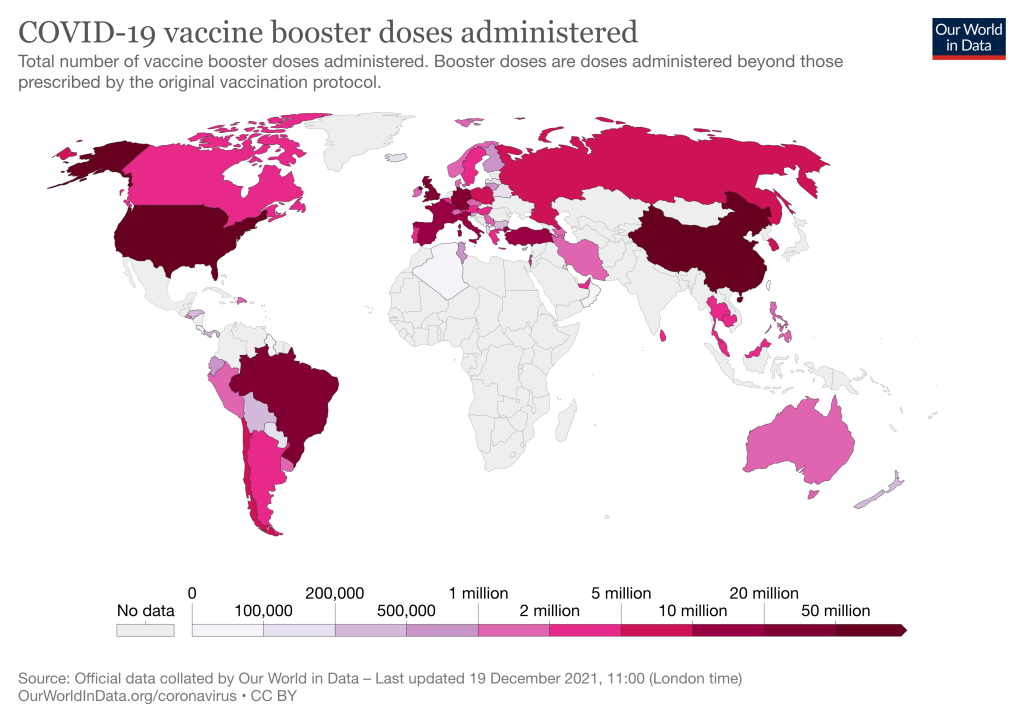

The rush on booster shots threatens to further deplete the global supply of COVID-19 vaccines even as many countries, especially low-income ones, have struggled to distribute first doses to their populations.

And, by exacerbating existing vaccine inequalities, protecting residents in richer countries could unintentionally help reproduce the same conditions that facilitated the rise of the Omicron variant itself.

Omicron and inequity

The Omicron variant was detected less than a month ago, and its exact origins remain unclear.

But scientists say that southern Africa offers particularly ripe conditions for the evolution of new variants, given the region’s low vaccination rates.

“Leaving large swaths of people unvaccinated means more opportunities for the virus to mutate,” Oumar Seydi, the Africa director of Bill & Melinda Gates foundation, wrote in Fortune.

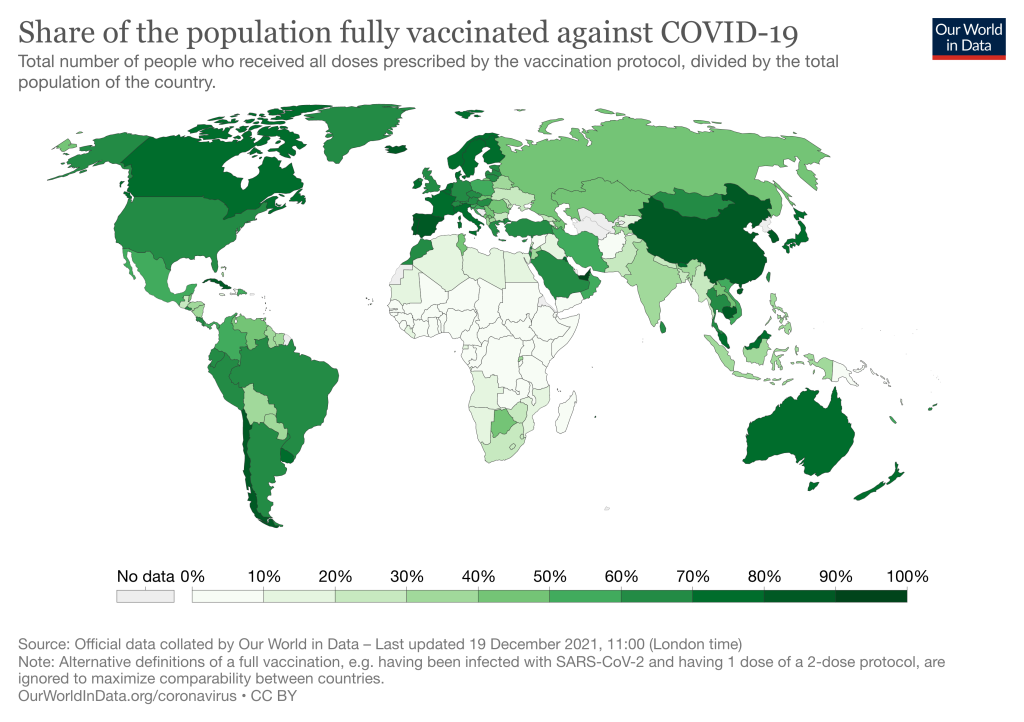

South Africa has fully vaccinated 26% of its population, below the global average of 48%, according to the New York Times.

South Africa’s neighbors including Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Namibia have similarly struggled to get access to vaccines, with fully immunized rates of 44%, 21%, and 13%, respectively.

Globally, a country’s national income has proved one of the most important determinants of a nation’s vaccination rate.

At the moment, globally just 7.6% of people living in low-income countries have received at least one dose of any shot, while richer countries like the U.S., the U.K., Canada, Japan and EU nations are beginning to boost at scale.

For every initial vaccine administered in a low- or lower-middle-income country, almost eight booster shots have gone into the arms of people in higher-income countries.

“The fact that boosters in rich countries are beginning to take priority over first and second doses in low- and lower-middle-income countries shows that we haven’t learned anything from the past two years,” said Jenny Ottenhoff, senior policy director for global health for the One Campaign, a nonprofit combating poverty and preventable diseases in Africa.

Fears are growing that Omicron’s emergence could make the problem worse. The World Health Organization (WHO) warned this week that “aggressive consumption” of COVID-19 doses by wealthy countries pushing their populations to receive booster shots could lead to a shortfall of 3 billion vaccines by early next year.

While many wealthy nations made commitments to share a certain number of vaccines in 2022, the countries are likely to “start sitting on those doses because of demand for boosters,” One Campaign’s Ottenhoff said.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, said this week that countries should prioritize boosters only for older and more vulnerable populations while unequal vaccine access persists.

“The WHO is concerned that such programmes will repeat the vaccine hoarding we saw this year, and exacerbate inequity…Let me be very clear: WHO is not against boosters. We’re against inequity. Our main concern is to save lives, everywhere,” Tedros said.

The Omicron variant may also pose a supply threat to higher-income countries. This has already been observed in Germany, which is seeing a shortage of mRNA vaccines and has tapped on its Eastern European neighbors to refill its supply.

Solving the inequity

One potential solution often flagged by public health activists is the TRIPS waiver, a proposal in the World Trade Organization that would waive intellectual-property protections for vaccines.

The emergence of the Omicron variant has renewed calls among activists for the WTO to pass the TRIPS waiver.

But even as the policy has garnered support from the U.S. and over 100 countries around the world, it has not been put to a vote, largely as a result of the European Union’s opposition to the proposal.

Toole, the Burnet Institute epidemiologist, says a TRIPS waiver could “double or triple” the number of COVID-19 vaccines that are available in coming years.

There are “proven companies in developing countries that have the capacity to make vaccines but cannot make them due to the waiver,” he says.

Human Rights Watch, a U.S.-based NGO, recently published a list of 100 companies across Asia, Latin America, and Africa that it says have the capacity to produce mRNA jabs if intellectual-property rights on COVID-19 vaccines were waived.

But companies like leading vaccine maker Pfizer say that a waiver would do little to boost supply, arguing that generic manufacturers may struggle to produce quality vaccines that use new mRNA technology and would disrupt the supply of raw materials they need to meet existing contracts.

Bryan Mercurio, a pharmaceutical law professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says Omicron’s emergence is proof that vaccine intellectual-property rights are necessary based on the fact that Pfizer and Moderna have already announced that that may release Omicron-specific vaccines by early next year.

Mercurio, who opposes a TRIPS waiver, says that this research is possible only because the market has made it financially viable for them to do so.

“We need continued R&D to tweak existing and produce new vaccines capable of dealing with the new variants,” he says.

Mercurio also questioned how much supply of existing vaccines remains an issue, mentioning that vaccine hesitancy in South Africa and other developing countries may be a “more important impediment” in equalizing vaccine distribution.

Other experts have also pointed to vaccine hesitancy as a way to explain low vaccination rates in southern Africa — making them an issue of vaccine demand, not supply.

But Jenny Ottenhoff at One Campaign says the situation is more complicated.

“Hesitancy exists in Africa like it exists everywhere on the planet,” Ottenhoff said.

But she explained that vaccine hesitancy is often used as an excuse for poor vaccination rates when in fact the problem is often that low-income countries have inadequate medical and logistical infrastructure to rapidly deliver doses to their populations.

“It is alarming how quickly the narrative has shifted on low-income countries to being a bit of a lost cause because of these barriers…It is not [a] level playing field,” she said.

COVAX, a United Nations–backed initiative to provide doses to low- and middle-income countries, says that its supply constraints have eased from earlier this year, but it that it will still likely fall 1.2 billion doses short of its 2 billion jab target in 2021.

Aurélia Nguyen, managing director of COVAX, told reporters last week it will be essential to maintain “sustainable, regular supply” to the initiative in the coming year from wealthier countries.

Vaccine inequity was likely an important factor in the emergence of Omicron, researchers say. Now, another variant may be lurking around the corner if vaccines are not more evenly distributed in coming months.

“As long as we have large portions of the world’s population that remain unvaccinated, we are going to have variants and the pandemic will be prolonged,” she said.

Originally published at https://fortune.com