The Health Transformation . Institute

research institute & knowledge portal

Joaquim Cardoso MSc*

Chief Researcher, Editor and Strategy Officer (CSO)

November 17, 2022

MSc* from London Business School — MIT Sloan Masters Program

Source: The Commonwealth Fund

Executive Summary [by the Editor of the Portal]

What are the findings?

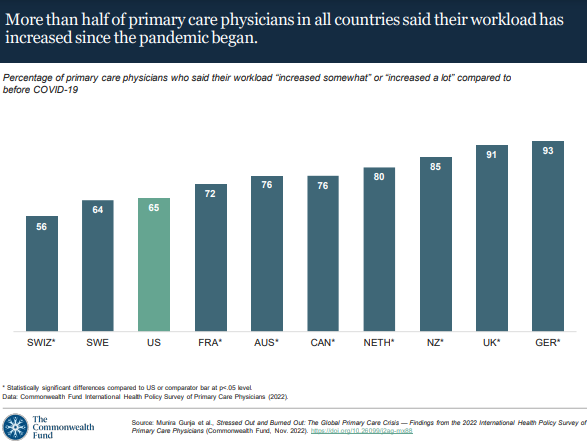

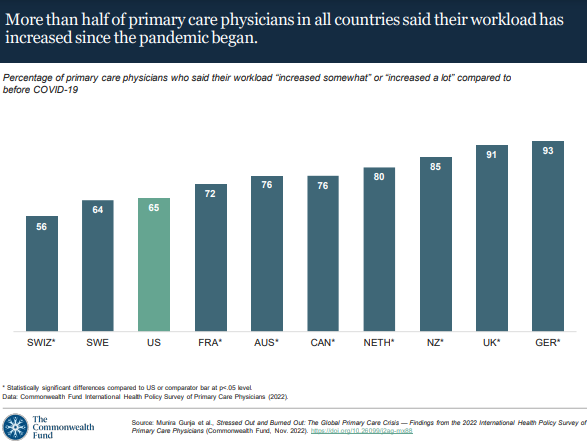

- Across the 10 high-income countries included in this study, most physicians reported increases in their workload since the beginning of the pandemic.

- Younger physicians (under age 55) were more likely to experience stress, emotional distress, or burnout and, in nearly all countries, were more likely to seek professional help compared to older physicians.

… most physicians reported increases in their workload since the beginning of the pandemic. Younger physicians (under age 55) were more likely to have negative consequences.

What is the impact?

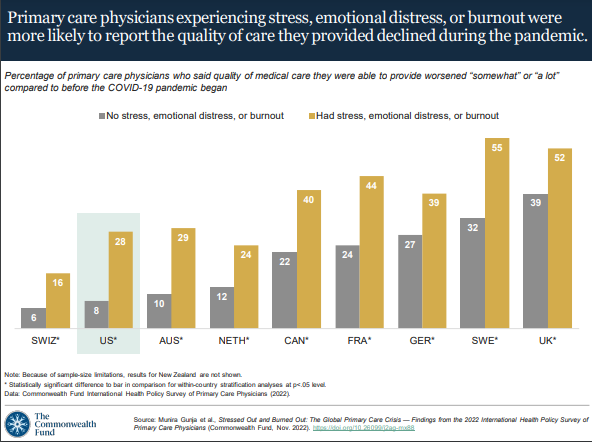

- Physicians who experienced stress, emotional distress, or burnout were more likely to report providing worse quality of care compared to before the pandemic.

What are the consequences?

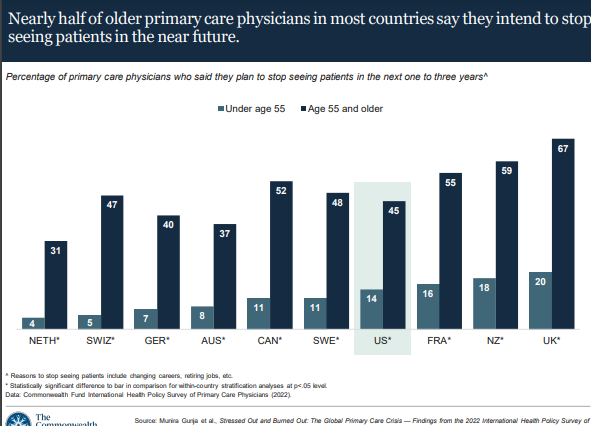

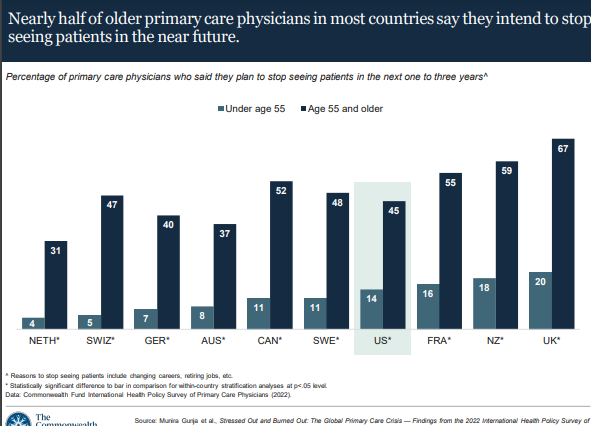

- Half or more of older physicians in most countries reported they would stop seeing patients within the next three years, leaving a primary care workforce made up of younger, more stressed, and burned-out physicians.

Half or more of older physicians in most countries reported they would stop seeing patients within the next three years, leaving a primary care workforce made up of younger, more stressed, and burned-out physicians.

What is the conclusion?

- Primary care is the backbone of a high-performing health care system

- But the Commonwealth Fund survey results show that health systems across the world are facing a primary care crisis of potentially declining quality of care as well as physically and mentally overburdened physicians.

- Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, it was projected that health systems globally would be facing a shortage of physicians in the coming years.10

- The survey results show that the high rates of physician burnout, stress, and emotional distress during the pandemic may very well accelerate this problem in most of the high-income countries we surveyed, where more than half of older primary care physicians in most countries said they would stop seeing patients within three years.

- In certain countries, such as New Zealand and the United Kingdom, even many younger physicians say they intend to stop practicing.

- In the United States, meanwhile, the percentage of medical students choosing to work in primary care continues to decline, with students opting instead for specialty fields.11

- It remains to be seen if the pandemic’s impact on the health workforce will have long-term consequences.

What Can We Do?

- Especially in the wake of COVID-19, policymakers and health system leaders need to take steps to ensure that physicians practice in healthy work environments that are conducive to delivering quality patient care.

- To start, ensuring that all primary care physicians have access to, and take advantage of, mental health services is critical.

- The United States has made some initial progress on this front. For example, the National Academy of Medicine’s “national plan” will build on the U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory, as well as related bipartisan policy efforts, to support the mental and behavioral well-being of health workers, including through the recruitment of additional mental health professionals dedicated to serving the health workforce.12

- Additional government investment in primary care is likely also part of the solution.

What are the first steps?

- In the United States, increasing Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for primary care services could help draw more medical school graduates into the field, as could loan forgiveness programs.13

- A number of countries are planning their own investments in primary care. Australia, which has committed $750 million toward improving primary care, recently established its Strengthening Medicare Taskforce to provide recommendations for growing its primary care workforce by the end of the year.14

- The United Kingdom pledged in 2019 to expand the number of general practitioners through several broad initiatives, including enhanced recruitment efforts among junior physicians, international recruitment, and deployment of multidisciplinary teams, although this major push has so far achieved limited success.15

- In all likelihood, it will require targeted efforts on multiple fronts to increase the supply of primary care physicians, allow physicians to see a more manageable number of patients, and ensure that everyone receives the quality care they expect.16

In all likelihood, it will require targeted efforts on multiple fronts to increase the supply of primary care physicians, allow physicians to see a more manageable number of patients, and ensure that everyone receives the quality care they expect.

What is the urgency?

- The time is now

Infographic

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

Stressed Out and Burned Out: The Global Primary Care Crisis

The Commonwealth Fund

Munira Z. Gunja, Evan D. Gumas, Reginald D. Williams II, Michelle M. Doty, Arnav Shah, Katharine Fields

NOVEMBER 17, 2022

Findings from the 2022 International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians

Introduction

For at least the past two decades, the United States and other countries around the world have been bracing for a shortage of physicians, a problem that has reached crisis proportions in recent years.1

Physician burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the shortage: at a time when regular health care has been disrupted and the prevalence of behavioral and mental health conditions has spiked, people’s access to basic primary care has been severely compromised.2

For at least the past two decades, the United States and other countries around the world have been bracing for a shortage of physicians, a problem that has reached crisis proportions in recent years.1

Physician burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the shortage

This brief presents the first findings from the 2022 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians to explore the effects of the pandemic on the primary care workforce across nations.

Conducted in 10 high-income countries, we compare changes in physician workload, stress, emotional distress, burnout, quality of care delivered, and physicians’ career plans.

We also examine differences in these measures by age, categorizing “younger physicians” as under age 55 — roughly the average age of U.S. physicians — and “older physicians” as age 55 and older.3

Survey Findings

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, most primary care physicians in each of the surveyed countries reported an increased workload, including nearly all physicians in Germany and the United Kingdom.

A greater backlog of patients needing care since the height of the pandemic, overall sicker patients, and more time spent on administrative tasks all appear to be contributors to greater physician workloads since the pandemic began.4

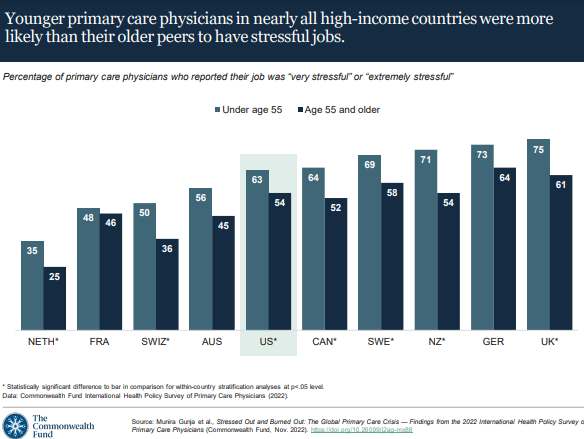

The Commonwealth Fund survey asked primary care physicians how stressful, if at all, their jobs are.

In each country, at least a third of younger physicians, under age 55, reported having a “very stressful” or “extremely stressful” job. In New Zealand, Germany, and the United Kingdom, nearly three-quarters of younger physicians reported job stress.

In contrast, in seven of the 10 countries, older primary care physicians, age 55 and older, were significantly less likely to report being stressed with their jobs.5 Nevertheless, more than half of older physicians in the majority of countries reported their jobs were stressful.

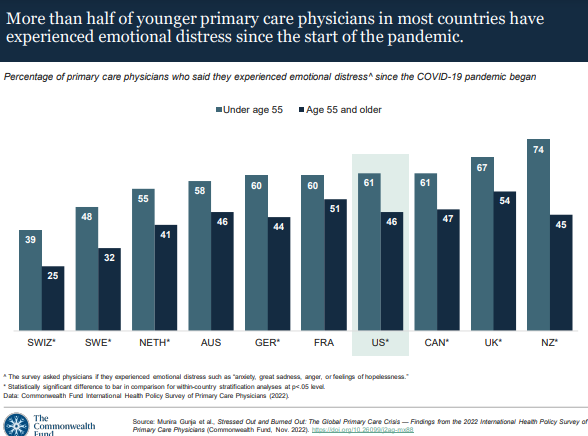

The Commonwealth Fund survey asked physicians if they had ever experienced emotional distress since the COVID-19 pandemic began, including anxiety, great sadness, anger, or feelings of hopelessness.

In all countries, at least two in five younger primary care physicians reported such feelings and emotions.

In nearly all countries, younger primary care physicians were significantly more likely to report emotional distress compared to their older counterparts.

These findings are consistent with research showing that emotional and psychological distress is higher among junior medical staff, even in countries with low COVID infection rates.

The reasons extend beyond the work environment and include the limited social supports that were available during lockdowns and uncertainty around the coronavirus’s life course and its impact.6

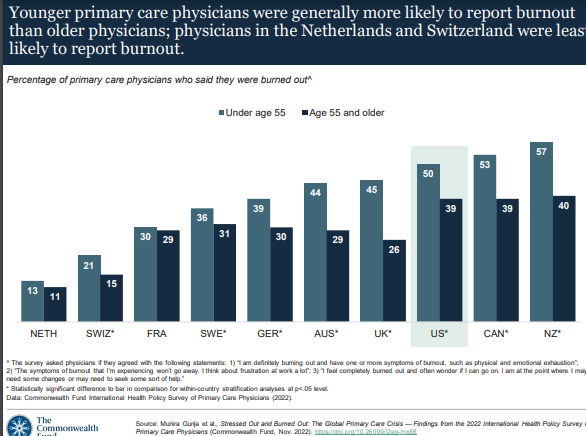

Primary care physicians also were asked to rate their current level of burnout. Physicians were considered to have burnout if they reported the following:

being physically or emotionally exhausted, having ongoing symptoms of burnout and frustration in the workplace, or feeling “completely burned out” — wondering if they can go on and needing to make changes or seek help.

In nearly all countries, a third or more of younger primary care physicians were experiencing burnout at the time of the survey; in Canada and New Zealand, over half have had burnout.

Younger physicians in all countries except the Netherlands and France appear to be experiencing burnout at significantly higher rates compared to older physicians.

Our findings of greater stress, emotional distress, and burnout among younger physicians are consistent with prior research.

Several factors may be at play, including longer work hours and additional strains from family caregiving responsibilities at home.7

Several factors may be at play, including longer work hours and additional strains from family caregiving responsibilities at home

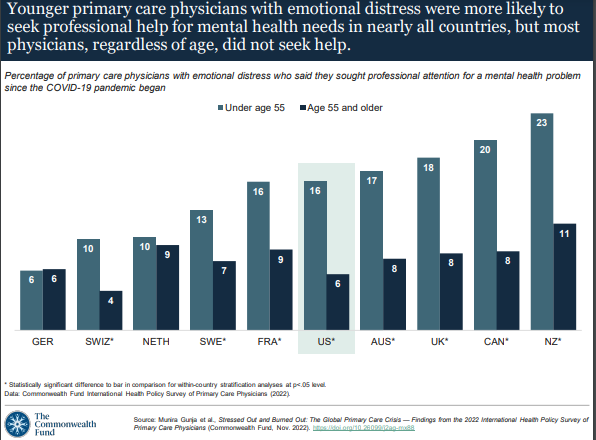

In most countries, while younger primary care physicians with emotional distress were significantly more likely than older ones to seek professional help for their mental health problems, the survey findings indicate that all physicians, regardless of age, sought treatment at fairly low rates — despite high levels of stress, burnout, and emotional distress within the profession.

In Germany, which has one of the highest levels of physician stress, fewer than one in 10 younger physicians sought help.

And in New Zealand, where rates of burnout and emotional distress were the highest, only a quarter of the younger primary care workforce have gotten help.

Having stress, emotional distress, or burnout can affect a physician’s ability to provide high-quality care.8

In the nine countries shown here, primary care physicians who reported having any of these burdens were significantly more likely to say the quality of care they were able to provide had worsened during the pandemic. (Because of sample-size limitations, results for New Zealand are not shown.)

Having stress, emotional distress, or burnout can affect a physician’s ability to provide high-quality care.8

Reports of worsening quality of care varied among physicians experiencing stress, emotional distress, or burnout: in Switzerland just 16 percent reported worse quality of care, compared to 55 percent in Sweden.

Reports of worsening quality of care varied among physicians experiencing stress, emotional distress, or burnout: in Switzerland just 16 percent reported worse quality of care, compared to 55 percent in Sweden.

Despite their comparatively lower rates of stress, emotional distress, and burnout, older primary care physicians in all surveyed countries were significantly more likely than their younger peers to report they plan to stop seeing patients within the next three years.

These rates varied: about one-third of older physicians in the Netherlands and Australia reported they will stop seeing patients, while the U.K. proportion was two-thirds.

Our findings show that with potentially a third or more of older physicians leaving the workforce in the near future, the majority of primary care physicians in all surveyed countries may soon be younger professionals burdened by stress and burnout (see the table).9

Our findings show that with potentially a third or more of older physicians leaving the workforce in the near future, the majority of primary care physicians in all surveyed countries may soon be younger professionals burdened by stress and burnout

Conclusion

Primary care is the backbone of a high-performing health care system.

But the Commonwealth Fund survey results show that health systems across the world are facing a primary care crisis of potentially declining quality of care as well as physically and mentally overburdened physicians.

Primary care is the backbone of a high-performing health care system. But the Commonwealth Fund survey results show that health systems across the world are facing a primary care crisis of potentially declining quality of care as well as physically and mentally overburdened physicians.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, it was projected that health systems globally would be facing a shortage of physicians in the coming years.10

Our survey results show that the high rates of physician burnout, stress, and emotional distress during the pandemic may very well accelerate this problem in most of the high-income countries we surveyed, where more than half of older primary care physicians in most countries said they would stop seeing patients within three years.

In certain countries, such as New Zealand and the United Kingdom, even many younger physicians say they intend to stop practicing.

In the United States, meanwhile, the percentage of medical students choosing to work in primary care continues to decline, with students opting instead for specialty fields.11

It remains to be seen if the pandemic’s impact on the health workforce will have long-term consequences.

What Can We Do?

Especially in the wake of COVID-19, policymakers and health system leaders need to take steps to ensure that physicians practice in healthy work environments that are conducive to delivering quality patient care.

To start, ensuring that all primary care physicians have access to, and take advantage of, mental health services is critical.

To start, ensuring that all primary care physicians have access to, and take advantage of, mental health services is critical.

The United States has made some initial progress on this front.

For example, the National Academy of Medicine’s “national plan” will build on the U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory, as well as related bipartisan policy efforts, to support the mental and behavioral well-being of health workers, including through the recruitment of additional mental health professionals dedicated to serving the health workforce.12

Additional government investment in primary care is likely also part of the solution.

In the United States, increasing Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for primary care services could help draw more medical school graduates into the field, as could loan forgiveness programs.13

A number of countries are planning their own investments in primary care.

Australia, which has committed $750 million toward improving primary care, recently established its Strengthening Medicare Taskforce to provide recommendations for growing its primary care workforce by the end of the year.14

The United Kingdom pledged in 2019 to expand the number of general practitioners through several broad initiatives, including enhanced recruitment efforts among junior physicians, international recruitment, and deployment of multidisciplinary teams, although this major push has so far achieved limited success.15

In all likelihood, it will require targeted efforts on multiple fronts to increase the supply of primary care physicians, allow physicians to see a more manageable number of patients, and ensure that everyone receives the quality care they expect.16

International comparisons allow the public, policymakers, and health care leaders to see alternative approaches to addressing common problems, including the primary care crisis.

The United States has an opportunity to learn what may be working, and not working, from other countries to strengthen primary care. Our analysis demonstrates that now is the time for immediate action.

APPENDIX: How we conducted this survey

The 2022 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians was administered to nationally representative samples of practicing primary care doctors in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These samples were drawn at random from government or private lists of primary care doctors in each country except France, where they were selected from publicly available lists of primary care physicians. Within each country, experts defined the physician specialties responsible for primary care, recognizing that roles, training, and scopes of practice vary across countries. In all countries, general practitioners (GPs) and family physicians were included, with internists and pediatricians also sampled in Switzerland and the United States.

The questionnaire was designed with input from country experts and pretested in most countries. Pretest respondents provided feedback about question interpretation via semistructured cognitive interviews. SSRS, a survey research firm, worked with contractors in each country to survey doctors from February through September 2022; the field period ranged from eight to 31 weeks. Survey modes (mail, online, and telephone) were tailored based on each country’s best practices for reaching physicians and maximizing response rates. Sample sizes ranged from 321 to 2,092, and response rates ranged from 6 percent to 40 percent. Across all countries, response rates were lower than in 2019. Final data were weighted to align with country benchmarks along key geographic and demographic dimensions.

References

See the original publication

Originally published at https://www.commonwealthfund.org on November 17, 2022.

Citation

Munira Z. Gunja et al., Stressed Out and Burned Out: The Global Primary Care Crisis — Findings from the 2022 International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians (Commonwealth Fund, Nov. 2022).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Robyn Rapoport, Rob Manley, and Christian Kline of SSRS; and David Blumenthal, Melinda Abrams, Chris Hollander, Bethanne Fox, Paul Frame, and Jen Wilson of the Commonwealth Fund.