Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF)

JANUARY 2014

Prepared by the APCD Council — Jo Porter, Denise Love, Ashley Peters, Jane Sachs, and Amy Costello

The Basics of All-Payer Claims Databases — A Primer for States

Introduction

- Over the past 10 years, a growing number of states have established state-sponsored all-payer claims database (APCD) systems to fill critical information gaps for state agencies, to support health care and payment reform initiatives, and to address the need for transparency in health care at the state-level to support consumer, purchaser, and state agency reform efforts.

- States with APCDs are responding to a need for comprehensive, multipayer data that allows states and other stakeholders to understand the cost, quality, and utilization of health care for their citizens.

- The purpose of this paper is to assist states embarking on APCD initiatives by highlighting key considerations for building statewide APCDs and potential solutions based on experiences in early-adopting APCD states.

Background

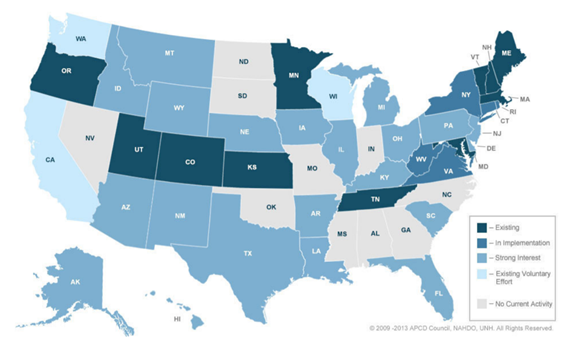

APCDs are large-scale databases that systematically collect medical claims, pharmacy claims, dental claims (typically, but not always), and eligibility and provider files from private and public payers. The first statewide APCD system was established in Maine in 2003. By 2008, five states (Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire) had passed legislation and established APCDs. By the end of 2010, four additional states (Minnesota, Tennessee, Utah, and Vermont) did the same. Since 2010, state interest in APCDs has grown at a steady pace. Currently, more than 30 states have, are implementing, or have strong interest in APCDs, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 1. State APCD Development, 2013

APCDs in the Context of Health Reform

While APCD development began before the Affordable Care Act (ACA) payment and delivery reform provisions, several components of the ACA, including patient-centered medical home and accountable care organizations (ACOs), the development of health insurance marketplaces, expansion of health information exchanges, and Medicaid expansion, have left many stakeholders seeking information about the current utilization and costs of health care in their states. APCD data about health care use and cost can contribute to effective policy decisions. For example, states across the country have implemented patient-centered medical home pilots, including several funded as Medicare Advanced Primary Care Demonstrations. APCDs are being used to evaluate the cost and quality impact of medical home pilots[1] [2] and to provide state stakeholders with information about health care utilization patterns and the needs of populations on a regional basis.[3] Overall, states with APCDs have a clearer baseline from which to evaluate the impact of reform efforts and to understand the health of and health care provided to their citizens.

Attributes and Characteristics of a Typical State APCD

There are both mandatory and voluntary APCDs, however the majority of APCDs established in the last 10 years are mandatory reporting initiatives. The examples in this paper focus on APCDs that are legally mandated initiatives in which payers are compelled to report by law.

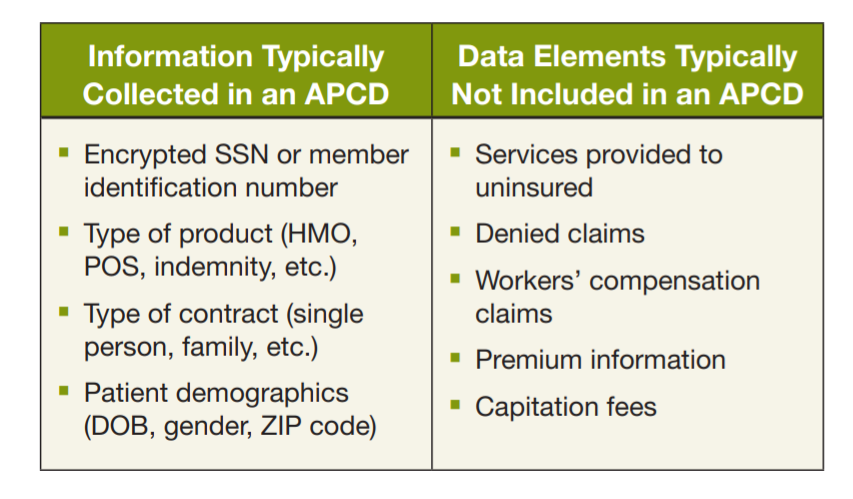

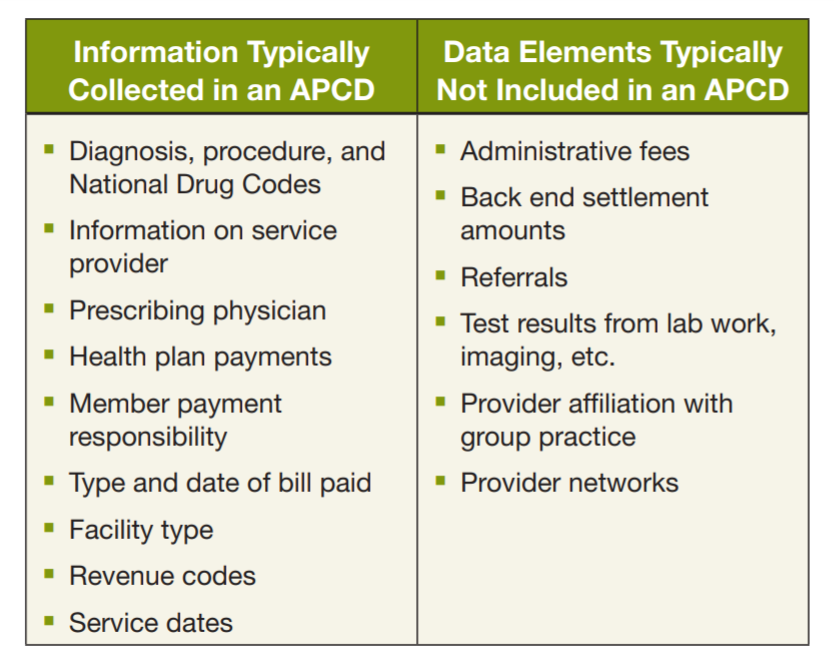

At a high level, APCD systems collect data from existing claims transaction systems used by health care providers and payers. The information typically collected in an APCD includes patient demographics, provider codes, and clinical, financial, and utilization data. Because of the difficulties involved with the collection of certain information, most states implementing APCD systems typically have not included a number of data elements, such as denied claims, workers’ compensation claims, and, because claims do not exist, services provided to the uninsured (Table 1).

Table 1. Common Included and Excluded Data Elements in State APCDs

Payers include insurance carriers, third party administrators, pharmacy benefit managers, dental benefit administrators, state Medicaid agencies, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program (FEHBP), and TRICARE administrators (uniformed services health program). States typically start populating their APCDs with data from commercial payers and third-party administrators licensed in the state and, if available, Medicaid claims data. Most pursue acquisition of Medicare claims data from CMS for beneficiaries in their respective states, though no state has incorporated TRICARE and FEHBP data into its APCD yet.

How to Develop an APCD

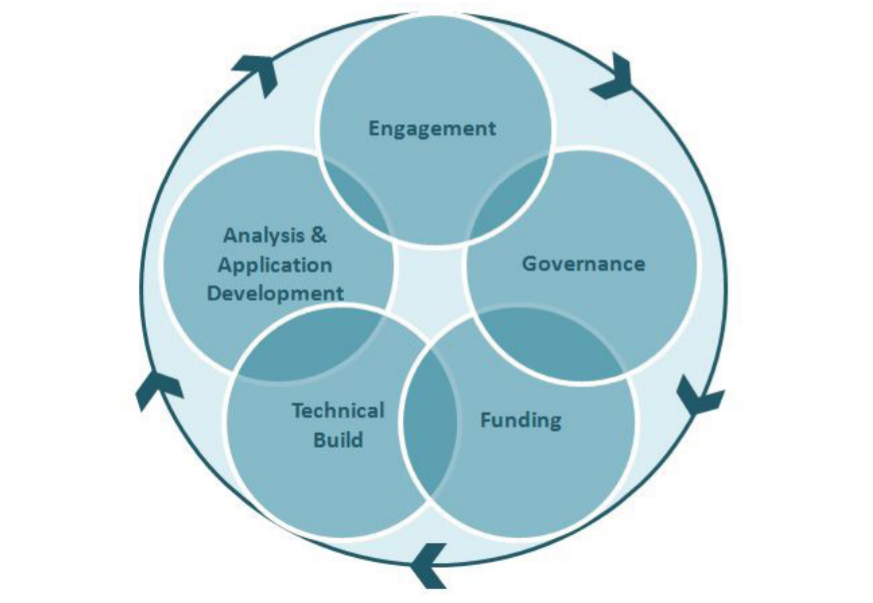

The first step to developing an APCD is to establish a system or process for guiding activities throughout the planning and implementation phases of APCD development. Generally, states with APCDs have followed the implementation framework depicted in Figure 2 as they move from planning to full implementation phases. Each component of this framework represents key steps or factors in the APCD development process. The arrows depict the interdependence of each of these components and the essential feedback loop, reflecting issues that must continuously be revisited as the system matures. For example, once the system is established, demand for information should lead to more robust analytics, bring in additional stakeholders.

Lesson Learned

Stakeholder engagement, including payer input, is essential to the success of a state APCD initiative. Because APCDs are still in the early stages of their development, they are rapidly evolving and changing. Responding to these changes requires participation by and support from all stakeholders, particularly in the planning process. Neglecting to involve key stakeholders early in the process can make progress challenging later on.

Figure 2. APCD Implementation Framework

Engagement

A key component to successful development of an APCD is early engagement from the full range of stakeholders that are likely to have interest in the APCD. States must first identify all stakeholders interested in an APCD and understand their chief interests and concerns. While each state’s stakeholder groups will vary, the key stakeholders for states to consider for inclusion are:

- Policy-makers: The APCD development effort typically begins as an executive branch initiative, a legislative initiative, or with a health commission that identifies the need for transparency and comparative information as a key component of health care reform. For governors and legislators, the data can be valuable to better understand the distribution of health care spending for both commercially and publicly insured citizens, and help identify opportunities for policy development to impact how care is paid for and delivered in a state. This can include policy decisions about providing support for payment reform efforts (e.g., Medicare demonstrations), understanding the impact of health insurance coverage expansions, and supporting of employers who are facing escalating health care costs. Ensuring that legislation is complete and reflects the full scope of issues that need to be addressed lays the foundation for the APCD system. See Governance for more information on what model legislation should entail.

- Payers: As the key submitters of APCD data, it is vital for states to include payers in stakeholder meetings to address concerns and pave the way for successful development of APCDs. Depending on the payers that conduct business in a given state, they may be familiar with APCDs from their involvement in other states, or APCDs may be novel to them. Some national payers required to submit data in multiple states have expressed concerns about the burden of submitting data in formats unique to each state.

- Health care providers: States have demonstrated that providers and health care systems can find value in having APCD data to measure provider cost and utilization across payers. However, health care providers are often interested in knowing how APCD data will be used and request certain protections about reporting data or analysis. In some states, like Maine, rules for the release of APCD data have included specific restrictions on releasing data that would reveal provider discount arrangements with payers.

- Employers and employer coalitions: Employers and employer coalitions often have a keen interest in APCD development. APCD data can provide a much more robust picture of the cost of health care services in the commercially insured population than employers can receive by reviewing claims reports just for their employees. The overall view of the commercial population can provide useful comparisons or benchmarks for employers that are tracking their own outcomes. For example, New Hampshire Purchasers Group on Health members have used APCD data to compare the cost and utilization patterns of their employees with the statewide commercially insured population from the APCD.

- State agencies: A number of state agencies can be important in APCD development. Generally, state health departments, state Medicaid offices, and state insurance departments are key state agencies in APCD governance and use of the APCD data. See Governance for more information on the role of state agencies.

- Consumers: APCD data, if analyzed and published for consumer purposes, can inform consumer understanding of health care spending and be a tool for making informed choices about health care services. Some states (e.g., New Hampshire and Maine) have created public-facing tools for consumers to identify health care prices and review the variation in prices of common services. These tools allow consumers to select where to receive health care services at lower costs, and have become increasingly important with consumer-directed health plans.

- Health Information Exchanges (HIEs): APCDs provide systemwide utilization and financial information, which can be enhanced with clinical data elements for special studies and outcomes measures. It is too early to determine how state APCDs and HIEs will converge. States are thinking strategically to leverage HIE resources, incorporate patient identifiers, and adopt shared services such as patient and provider directories. While it is unlikely that APCDs will be integrated with HIEs in the near term, and it is likely that HIEs and APCDs will be distinctly separate initiatives, the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act’s Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health provisions may provide unique opportunities for states to build local information system capacity to meet state information needs.

- Health Insurance Exchanges (HIX): Some states have been able to leverage funding and shared services from HIE or HIX entities in their states, which strengthens the business case for both APCD and the exchanges. HIX funding opportunities for states have had, as a key component, a focus on health cost transparency, recognizing the need for it to build a better health insurance marketplace and determine how their marketplace will be operated and governed.[4] There is anticipation that APCD information, if used by the HIX, can provide key information about states’ market coverage and structure decisions, including evidence of adverse selection and consumer decisions, resulting in the selection of high-quality, high-value health care options. Thus, APCD and HIX efforts can be synergistic.

Lesson Learned

Political and technical environments vary across states; and, consequently, so do APCDs. Balancing local flexibility in approaches with national standards will continue to pose challenges, especially in these early years, as states experiment with innovative solutions at the local levels. Similarly, legislation should be designed in a broad way whenever possible; more in-depth specifics can be included in the rules and regulations, which are often easier to adjust and adapt over time. As state systems evolve, there will be a migration toward uniformity in data elements and reporting, similar to the migration of national standards with hospital discharge data systems.

Governance

APCD governance includes 1) authorization; 2) rules that specify the technical and logistical aspects of the APCD; and 3) an oversight entity and management of the APCD “home.” The APCD Council website has state profiles which identify the various components of APCD governance for each APCD state. The following section details each of the three components of APCD governance.

Authorization

Typically, APCD legislation provides broad authority and defines the intended use of the APCD. It can also define the APCD organizational “home,” governance structure, and reporting requirements of the APCD. APCD legislation also generally references the elements of the system and procedures that will support the development of an APCD. For example, the legislation may refer to general rule-making or data submission specifications to be developed by a governing body. Legislation to authorize an APCD typically needs to also include:

- The authority to enforce its provisions, such as penalties for payers that do not report or for misuse of the data.

- Specific legal authority for pharmacy benefit managers and third-party administrators to report the data because states vary in their licensing requirements.

Administrative Rules

For most states, the administrative rules are where details about APCD data collection requirements (e.g., format and timing of submission, specifications of data elements, and thresholds for payers that are required to submit data) are defined. By keeping the detail in the administrative rules, changes to a data element or submission schedule can be handled through rule-making, which is typically less time consuming than modifying the legislation. However, each state will have to assess its legislative and rulemaking processes to determine the most efficient way to design a flexible but comprehensive APCD. While there is no “model,” most state APCD administrative rules define the following:

- data elements and definitions for collection;

- submission format and timelines;

- review and validation process;

- penalties for noncompliance; and

- data release and use policies.

Determining what data and information will be released and to whom can be the most sensitive aspect of APCD implementation. There is significant variation in policies and practices across states, reflecting differing viewpoints about the balance between making the data available for use and controlling release to address concerns of provider and/or patient identification. States generally de-identify the data using encryption and statistical methods to mask the identity of the individuals in the database. Regulations that specify data access and release policies vary according to state legal and political environments (e.g., Minnesota does not release data to external organizations because of privacy concerns; Maine restricts the identification of provider discount arrangements). In some states, de-identified and research files are made available for qualified users and uses. Other states limit data access to state government only. Many agencies maintaining APCDs have decades of experience collecting and disseminating hospital data without privacy breaches and use similar statistical and management controls for their APCD practices.

The technical considerations for the issues that are defined in the rules, as described above, are further addressed in the Technical Build section.

APCD Oversight

The entity responsible for APCD oversight varies by state. When making a decision about APCD management, a state must take into account the intended use of the APCD, the financial and staffing resources available to manage the APCD and the experience in data management efforts of different state agencies. The following are examples of where some states have located their APCD “home”:

- Department of Health (Utah, Minnesota)

- Independent state agency (West Virginia, Maine)

- Health and insurance departments with overlapping responsibilities (New Hampshire)

- External, non-governmental agency (Colorado)

Lesson Learned

Funding and sustaining APCD reporting initiatives is challenging, especially in these early stages in which the potential value of APCD information is still not fully realized. States have relied on experience from outside vendors, and built internal and external organizational capacity to support APCD development. With more states implementing APCDs, the business case for statewide APCDs will emerge and quantify the return on investments in terms of efficiency, accountability, and transparency.

Funding

Another key piece of the framework for establishing an APCD is funding. Understanding funding opportunities can inform where the APCD should be housed (e.g., how can APCD activity be aligned to the state agencies with funding to support the effort), how the data are intended to be used (e.g., can federal dollars be used if the data will support federally funded projects), and what advisory capacities are needed (e.g., if multiple agencies or projects fund the APCD, what are the roles of the different funders). States have a variety of strategies for funding APCDs and financially sustaining the databases over the long term. Public APCDs are typically funded, at least in part, through general appropriations or industry fee assessments. Many states also identify grant funding to support the initial phases of APCD development. For example, the APCD in Colorado received funding through grants from the Colorado Health Foundation and The Colorado Trust. Some states (Rhode Island and New York) have been able to use the federal Beacon Community Program and other grants to support APCD development, because these data are critical components of the state’s efforts to improve health care for their citizens. More recently, states have included APCD improvement and development as a component of federal rate review grants (Hawaii and Kansas). New Hampshire’s APCD is used by its Medicaid program and leverages funding from Medicaid to support it.

In some states, the expectation is that a portion of long-term maintenance funding will come from data product sales. As valuable as APCD data are expected to be to many stakeholders, states are cautioned about sustaining the APCD solely through sales of data products. Based on the state experience to date, data sales revenue will need to be supplemental to other core revenue streams.

Technical Build

The technical build of an APCD is likely the most complicated step in the framework of developing an APCD. Critical to this step are discussions and technical workgroup meetings with key stakeholders, including payers, to define the reporting requirements for payers that will be submitting their claims data to the authorized APCD agency.

To accurately anticipate the technical needs of the APCD, states need to consider the following:

- Number of covered lives: The size of the state’s population determines how many people and claims are likely to be part of the system. States with large populations will need sufficient computing and storage capacity to analyze and accommodate terabytes of data associated with the eligibility, medical, pharmacy, and dental claims files.

- Number of payer feeds or data sources: The main driver of cost and complexity for an APCD is typically the number of different data sources and platforms with which the collecting agency must interact, which is primarily dependent upon the specific health insurance market of each state. The number of payer feeds in each state APCD can vary greatly. For example, the state of Vermont has 10 commercial payer feeds compared to Minnesota, which has nearly 200. Driving these totals is the fact that one commercial payer could have multiple information system/claims processing platforms (typically delineated by product), each resulting in a separate set of data feeds. In addition, most APCDs will capture eligibility, medical, and pharmacy files; some states will also include dental claims and provider files, thereby increasing the number of data sources and data aggregation. The APCD agency must interact with and test data from each separate platform and monitor compliance and data quality from all sources.

Example Reporting Thresholds

- Maine: minimum 50 covered lives.

- Utah: minimum 2,500 covered lives.

- Maryland: minimum $1 million in annual premiums.

- Kansas: minimum market share of 1 percent.

To make the number of submissions manageable and to minimize the burden on payers with very small populations in a given state, rules for reporting thresholds (e.g., defining which payers have to submit) based on factors such as the number of covered lives, total revenue from premiums, or market share are typically developed. This provides efficiency in capturing the majority of the population for both the state and the payers.

The most common variable for defining which payers have to submit is the number of covered lives. States have found that using the covered lives threshold is more straightforward than thresholds set on dollar values that can be influenced by rates and premium changes.

- Adoption of a common, nationally recognized format for state APCD data collection vs. a state-specific format: Because claims data are generated for billing purposes, the data elements are generally available across payer systems, making claims a cost-effective data source for states. Uniformity is important, both for comparability across states and to allow states to leverage one another’s work. Nationally recognized data formats allow for easier sharing of analytic codes and applications between states. For payers, the use of nationally recognized formats can reduce the payers’ burden to submit data to different states. Greater standardization of APCD operation and policies across states will enable cost-effective regional, and possibly national, databases. There are initiatives underway to standardize data reporting formats. Early efforts in standardization have resulted in industry reporting standards that align with both state reporting needs and payer reporting capabilities. At the same time, while such standardization of data elements and format across states is beneficial for both states and payers, there needs to be some flexibility for local information needs.

- Anticipated needs for analysis and reporting: Another important, but highly variable, set of activities in an APCD is data analysis. Analytic agendas and functions can range from basic reports to sophisticated, risk-adjusted, or modeled comparative reports. General considerations in developing the analytic agenda for a state include:

- What information will be produced and available? Are there plans for the production and/or maintenance of public websites?

- Who will manage the requests for data and reporting, and who will manage the dissemination?

- Is there existing staff and resource (e.g., computing, software) capacity at the agency where the APCD is to be housed (e.g., insurance department, health department, or other type of arrangement such as a state-sponsored private entity) to do analysis?[5]

- Outsourcing APCD functions: In most states, data collection and aggregation functions are performed through contracts with vendors. Start-up implementation is typically labor-intensive, and therefore costly, due to the need to test payer data submissions extensively at the outset of system development. Historical files are tested and initially loaded, often including multiple years of retrospective data.

Aggregating claims data files across payers is a complex process, with technical and political challenges. For example, payers may have individual provider files, homegrown code sets, and may capture the same types of data in different ways. In addition, payers may change claims and eligibility systems, causing issues in the data. Quality assurance review of the data is important to identify and resolve data issues quickly. Most states that implement APCD reporting have defined policies and processes for establishing error thresholds for key fields, but to date there is no uniform standard for editing and establishing these thresholds. Generally, the issues need to be addressed through conversations with the payers, and resubmissions of data to address errors may be necessary. This underscores the importance of being engaged with the payer community throughout APCD development and maintenance. States must design the processes and specifications that address their unique situations, but states have learned that the reporting specifications must be aligned with payer system capabilities.

As with data collection, states often outsource the analytic functions of the APCD to contracted vendors. However, states have benefited from retaining some analytic capacity in-house in addition to the contracted analytics. Importantly, as APCD analytics evolve, open-source and non-proprietary solutions and tools will emerge, as has been seen with hospital discharge data analytics. States with APCDs and states interested in developing the data systems have identified the need for common, comparable measures that could be produced by states. Standardized measures, if developed and used across state APCDs, are less likely to need special auditing or training for payers than unique or state-specific measures. By borrowing or accessing standardized measures and tools, as the state of Maine did in replicating the work of the New Hampshire Insurance Department in building the HealthCost consumer reporting tool, states can more quickly and cost-effectively concentrate on interpreting and reporting data instead of measure development activities.

Conclusion

Statewide APCDs are becoming a core health care data set in a growing number of states. While states are adopting technical approaches that align with their industry structure and political environments, there are common challenges. States that have APCDs in place have been able to identify and address many issues in APCD development. Early and ongoing engagement with key stakeholders, including policy-makers, payers, employers, health care providers, state agencies, consumers, and other related data initiatives, is key to successful planning for, and implementation of, an APCD. State approaches to governance are varied, reflecting state-specific considerations about funding options, technical capacity, anticipated uses for the APCD, and statutory authority for data collection, storage, and release. APCDs are complex data systems, with a number of issues impacting how complicated the data collection, aggregation, and analytic functions may be (e.g., the number of covered lives, number of data feeds, etc.). Many states have outsourced APCD development and analysis functions to address this complexity. However, states continue to find common issues with APCD development, and also have common interests in how to use the data. States working collectively on common issues can leverage solutions more effectively than each state working independently. Areas for continued collective action include development of national standards, both in data and measures. Now and in the future, state APCDs provide the unique data to support the development of comparable information about the cost, effectiveness, and performance of the health care delivery system at the local, state, and national levels.

ABOUT THE APCD COUNCIL

This paper was written by the AllPayer Claims Database (APCD) Council with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health and Value Strategies program. The APCD Council is a learning collaborative of government, private, nonprofit, and academic organizations focused on improving the development and deployment of state-based APCDs. The APCD Council is convened and coordinated by the New Hampshire Institute for Health Policy and Practice (NHIHPP) at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) and the National Association of Health Data Organizations (NAHDO). The APCD Council work focuses on shared learning, technical assistance to state APCDs, and catalyzing states to achieve mutual goals.

ABOUT STATE HEALTH AND VALUE STRATEGIES

State Health and Value Strategies, a program funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, provides technical assistance to support state efforts to enhance the value of health care by improving population health and reforming the delivery of health care services. The program is directed by Heather Howard at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University.

ABOUT THE ROBERT WOOD JOHNSON FOUNDATION

For more than 40 years the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has worked to improve the health and health care of all Americans. We are striving to build a national culture of health that will enable all Americans to live longer, healthier lives now and for generations to come. For more information, visit www.rwjf.org. Follow the Foundation on Twitter at www.rwjf.org/twitter or on Facebook at www.rwjf.org/facebook.

Endnotes

1. Medical Home Pillar Project. Bow, N.H.: New Hampshire Citizens Health Initiative, 2013, http://citizenshealthinitiative.org/ medical-home-project (accessed September 2013).

2. Blueprint for Health. Montpelier, Vt.: State of Vermont Agency of Administration, 2013, http://hcr.vermont.gov/blueprint (accessed September 2013).

3. Accountable Care Project. Bow, N.H.: New Hampshire Citizens Health Initiative, 2013, http://citizenshealthinitiative.org/ accountable-care-project (accessed September 2013).

4. Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, State Marketplace Resources. Baltimore: Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, 2013,www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Health-Insurance-Marketplaces/State-Marketplace-Resources. html, (accessed October 2013).

5. “Analytic Plan Guidance Document for States Developing All-Payer Claims Database Analytic Plans.” Salt Lake City: National Association of Health Data Organizations. (Forthcoming).

[1] Medical Home Pillar Project. Bow, N.H.: New Hampshire Citizens Health Initiative, 2013, http://citizenshealthinitiative.org/ medical-home-project (accessed September 2013).

[2] Blueprint for Health. Montpelier, Vt.: State of Vermont Agency of Administration, 2013, http://hcr.vermont.gov/blueprint (accessed September 2013).

[3] Accountable Care Project. Bow, N.H.: New Hampshire Citizens Health Initiative, 2013, http://citizenshealthinitiative.org/ accountable-care-project (accessed September 2013).

[4] Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, State Marketplace Resources. Baltimore: Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, 2013,www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Health-Insurance-Marketplaces/State-Marketplace-Resources. html, (accessed October 2013).

[5] “Analytic Plan Guidance Document for States Developing All-Payer Claims Database Analytic Plans.” Salt Lake City: National Association of Health Data Organizations. (Forthcoming).

Originally published at: