the health strategist

multidisciplinary research institute

for continuous transformation in health and tech

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Founder and Chief Researcher & Editor

February 26, 2023

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Experts are split about how much control people will retain over essential decision-making as digital systems and AI spread.

- They agree that powerful corporate and government authorities will expand the role of AI in people’s daily lives in useful ways.

- But many worry these systems will diminish individuals’ ability to control their choices

DEEP DIVE

The Future of Human Agency

BY JANNA ANDERSON AND LEE RAINIE

Advances in the internet, artificial intelligence (AI) and online applications have allowed humans to vastly expand their capabilities and increase their capacity to tackle complex problems.

These advances have given people the ability to instantly access and share knowledge and amplified their personal and collective power to understand and shape their surroundings.

Today there is general agreement that smart machines, bots and systems powered mostly by machine learning and artificial intelligence will quickly increase in speed and sophistication between now and 2035.

As individuals more deeply embrace these technologies to augment, improve and streamline their lives, they are continuously invited to outsource more decision-making and personal autonomy to digital tools.

Some analysts have concerns about how business, government and social systems are becoming more automated.

They fear humans are losing the ability to exercise judgment and make decisions independent of these systems.

Others optimistically assert that throughout history humans have generally benefited from technological advances.

They say that when problems arise, new regulations, norms and literacies help ameliorate the technology’s shortcomings.

And they believe these harnessing forces will take hold, even as automated digital systems become more deeply woven into daily life.

Thus the question: What is the future of human agency?

Pew Research Center and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center asked experts to share their insights on this; 540 technology innovators, developers, business and policy leaders, researchers, academics and activists responded. Specifically, they were asked:

By 2035, will smart machines, bots and systems powered by artificial intelligence be designed to allow humans to easily be in control of most tech-aided decision-making that is relevant to their lives?

The results of this nonscientific canvassing:

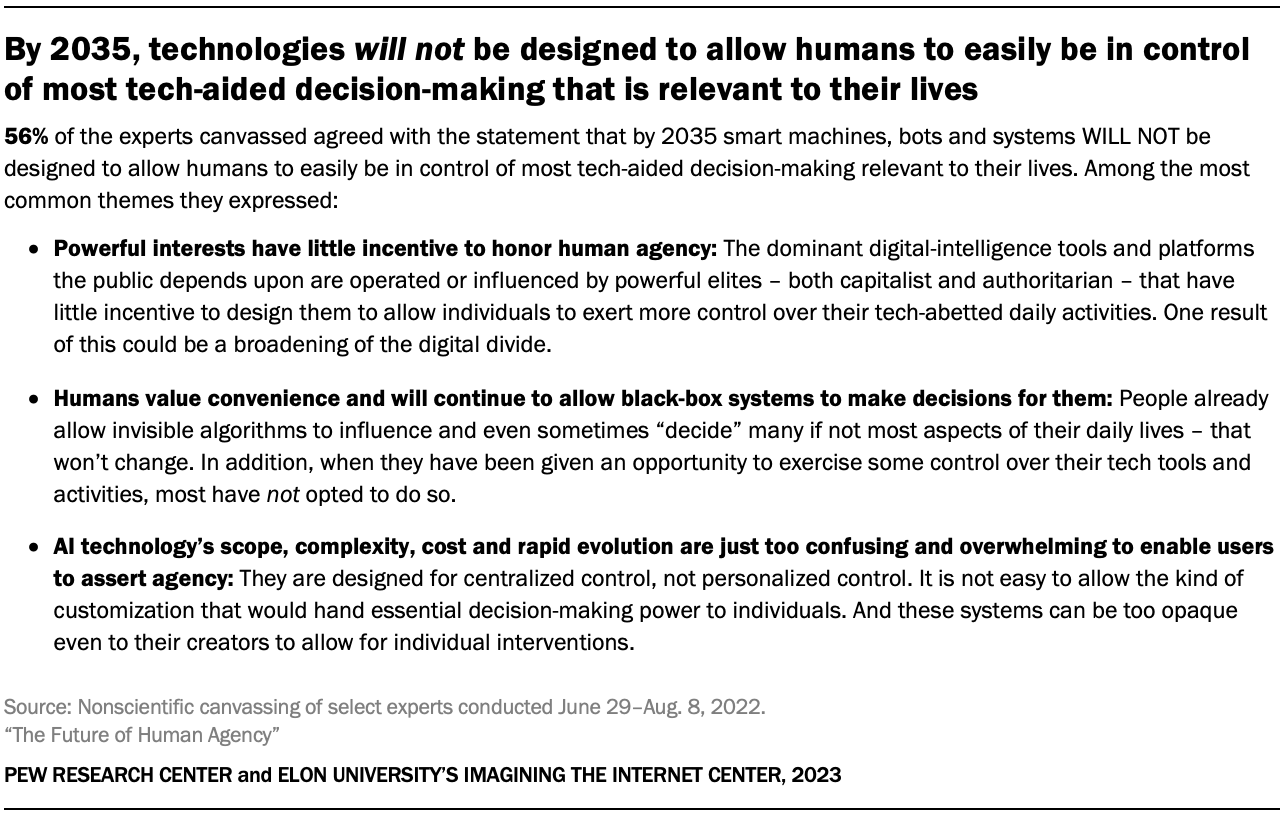

- 56% of these experts agreed with the statement that by 2035 smart machines, bots and systems will not be designed to allow humans to easily be in control of most tech-aided decision-making.

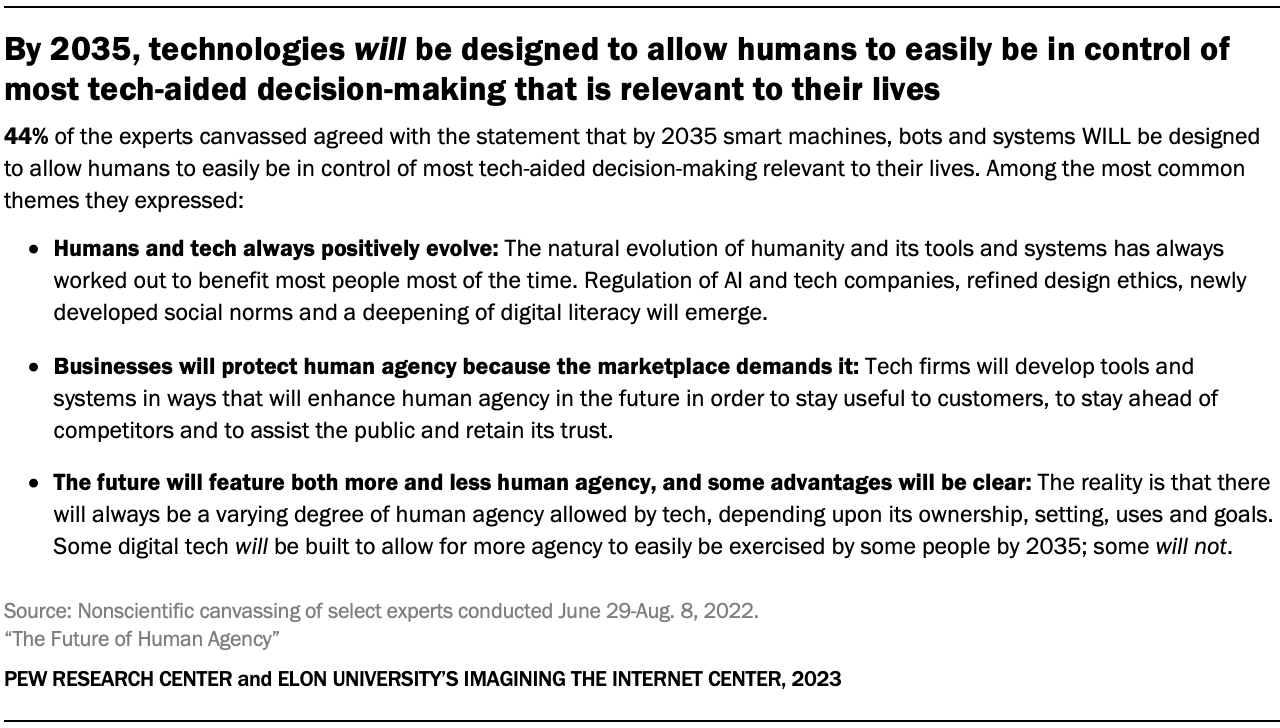

- 44% said they agreed with the statement that by 2035 smart machines, bots and systems will be designed to allow humans to easily be in control of most tech-aided decision-making.

It should be noted that in explaining their answers, many of these experts said the future of these technologies will have both positive and negative consequences for human agency.

They also noted that through the ages, people have either allowed other entities to make decisions for them or have been forced to do so by tribal and national authorities, religious leaders, government bureaucrats, experts and even technology tools themselves.

In addition, these experts largely agree that digital technology tools will increasingly become an integral part of people’s decision-making.

The tools will provide ever-larger volumes of information to people that, at minimum, will assist them in exploring choices and tapping into expertise as they navigate the world.

At the same time, experts on both sides of the issue also agree that the current moment is a turning point that will determine a great deal about the authority, autonomy and agency of humans as the use of digital technology spreads into more aspects of daily life.

At the same time, experts on both sides of the issue also agree that the current moment is a turning point that will determine a great deal about the authority, autonomy and agency of humans as the use of digital technology spreads into more aspects of daily life.

Collectively, people will face questions such as:

- What are the things humans really want agency over?

- When will they be comfortable turning to AI to help them make decisions?

- And under what circumstances will they be willing to outsource decisions altogether to digital systems?

Some outlined the stakes:

Alf Rehn, professor of innovation, design and management at the University of Southern Denmark, observed, “The future will clearly cut both ways. On the one hand, better information technologies and better data have improved and will continue to improve human decision-making. On the other, black box systems and non-transparent AI can whittle away at human agency, doing so without us even knowing it is happening. The real challenge will lie in knowing which dynamic is playing out strongest in any given situation and what the longer-term impact might be.”

Barry Chudakov, founder and principal, Sertain Research, predicted, “By 2035, the relationship between humans and machines, bots and systems powered mostly by autonomous and artificial intelligence will look like an argument with one side shouting and the other side smiling smugly. The relationship is effectively a struggle between the determined fantasy of humans to resist (‘I’m independent and in charge and no, I won’t give up my agency!’) and the seductive power of technology designed to undermine that fantasy (‘I’m fast, convenient, entertaining! Pay attention to me!’)”

Kathryn Bouskill, anthropologist and AI expert at the Rand Corporation, said, “Some very basic functions of everyday life are now completely elusive to us. People have little idea how we build AI systems, control them and fix them. Many are grasping for control, but there is opaqueness in terms of how these technologies have been created and deployed by creators who oversell their promises. Right now, there is a huge chasm between the public and AI developers. We need to ignite real public conversations to help people fully understand the stakes of these developments.”

The experts replying to this canvassing sounded several broad themes in their answers. Among those who said that evolving digital systems will not be designed to allow humans to easily be in control of most tech-aided decision-making, the main themes are cited here:

Here is a small selection of expert answers that touch on those themes:

Greg Sherwin, a leader in digital experimentation with Singularity University, predicted, “Decision-making and human agency will continue to follow the historical pattern to date: It will allow a subset of people with ownership and control of the algorithms to exert exploitative powers over labor, markets and other humans. They will also operate with the presumption of guilt with the lack of algorithmic flagging as a kind of machine-generated alibi.”

J. Nathan Matias, leader of the Citizens and Technology Lab at Cornell University, said, “Because the world will become no less complex in 2035, society will continue to delegate important decision-making to complex systems involving bureaucracy, digital record-keeping and automated decision rules. In 2035 as in 2022, society will not be asking whether humans are in control, but which humans are in control, whether those humans understand the consequences of the systems they operate, whether they do anything to mitigate the harms of their systems and whether they will be held accountable for failures.”

Alan Mutter, consultant and former Silicon Valley CEO, observed, “Successive generations of AI and iterations of applications will improve future outcomes, however, the machines — and the people who run them — will be in control of those outcomes. AI is only as good as the people underlying the algorithms and the datasets underlying the systems. AI, by definition, equips machines with agency to make judgments using large and imperfect databases. Because AI systems are designed to operate more or less autonomously, it is difficult to see how such systems could be controlled by the public, who for the most part are unlikely to know who built the systems, how the systems operate, what inputs they rely on, how the system was trained and how it may have been manipulated to produce certain desired and perhaps unknown outcomes.”

Christopher W. Savage, a leading expert in legal and regulatory issues based in Washington, D.C., wrote, “In theory, a well-deployed AI/ML [machine learning] system could help people make rational decisions in their own best interest under conditions of risk and involving stochastic processes. But I suspect that in practice most AI/ML systems made available to most people will be developed and deployed by entities that have no interest in encouraging such decisions. They will instead be made available by entities that have an interest in steering people’s decisions in particular ways.”

Alejandro Pisanty, Internet Hall of Fame member, longtime leader in the Internet Society and professor of internet and information society at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, predicted, “There are two obstacles to human agency triumphing: enterprise and government. Control over the technologies will be more and more a combination of cooperation and struggle between those two forces, with citizens left very little chance to influence choices. … The trends indicate that the future design of decision-making tech will most likely not be determined by the application of science and well-reasoned, well-intended debate. Instead, the future is to be determined by the agendas of commercial interests and governments, to our chagrin.”

Heather Roff, nonresident fellow in the law, policy and ethics of emerging military technologies at the Brookings Institution and senior research scientist at the University of Colorado-Boulder, wrote, “Most users are just not that fluent in AI or how autonomous systems utilizing AI work, and they don’t really care. Looking at the studies on human factors, human systems integration, etc., humans become pretty lazy when it comes to being vigilant over the technology. Humans’ cognitive systems are just not geared to ‘think like’ these systems. So, when one has a lack of literacy and a lazy attitude toward the use of such systems, bad things tend to happen. People put too much trust in these systems, they do not understand the limitations of such systems and/or they do not recognize how they actually may need to be more involved than they currently are.”

Paul Jones, emeritus professor of information science at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, said, “How automation takes over can be subtle. Compare searching with Google to searching CD-ROM databases in the 1990s. Yes, humans can override search defaults, but all evidence shows they don’t and for the most part they won’t.

“

In information science, we’ve known this for some time. Zipf’s Law tells us that least effort is a strong predictor of behavior — and not just in humans. We once learned how to form elegant search queries. Now we shout ‘Alexa’ or ‘OK, Google’ across the room in a decidedly inelegant fashion with highly simplified queries. And we take what we get for the most part. The more often automated results please us, the more we trust the automation. While such assistance in cooking, math, money-management, driving routes, question-answering, etc., may seem benign, there are problems lurking in plain sight.

“

As Cory Doctorow dramatizes in ‘ Unauthorized Bread,’ complicated access, ownership agreements and other controls will and do put the users of even the most-simple networked technologies in a kind of centralized control that threatens both individual autonomy and social cohesion. The question you didn’t ask is: ‘Is this a good thing for humans?’ That’s a more complicated and interesting question. I hope that one will be asked of the designers of any automated control system heading for 2035 and beyond.”

A top editor for an international online news organization wrote, “At present, many people on Earth have already effectively outsourced — knowingly or unknowingly — their tech-aided decisions to these systems. Many of these people do not give extensive thought to the reality of their personal agency in such matters. In many cases this is because they do not fully understand such processes. Perhaps they have fully invested their faith into them, or they simply do not have the time nor inclination to care. Save a most unlikely paramount event that causes society to radically reevaluate its relationship to these systems, there is no reason to conclude at present that these common prevailing attitudes will change in any revolutionary way.

“

For all intents and purposes, many people’s tech-aided decision-making is largely out of their control, or they do not know how to more-capably direct such systems themselves. Many of the most critical tech-aided decisions in practice today do not lend themselves to clear control through the conscious agency of the individual.

“

The way in which automated recurring billing is designed often does not clearly inform people that they have agreed to pay for a given service. Many people do not understand the impact of sharing their personal information or preferences to set up algorithm-generated recommendations on streaming services based on their viewing behavior, or other such seemingly simple sharing of bits of their background, wants or needs. They may not know of their invariable sacrifice of personal privacy due to their use of verbally controlled user interfaces on smart devices, or of the fact that they are giving over free control over their personal data when using any aspect of the internet.

“

For better or worse, such trends are showing no clear signs of changing, and in all likelihood are unlikely to change over the span of the next 13 years. The sheer convenience these systems provide often does not invite deeper scrutiny. It is fair to say tech design often gives the seeming appearance of such control, the reality of which is often dubious.”

Several main themes also emerged among those who said that evolving digital systems will be designed to allow humans to easily be in control of most tech-aided decision-making. They are cited here:

Here is a small selection of expert answers that touch on those themes:

Marc Rotenberg, founder and president of the Center for AI and Digital Policy, said, “Over the next decade, laws will be enacted to regulate the use of AI systems that impact fundamental rights and public safety. High standards will be established for human oversight, impact assessments, transparency, fairness and accountability. Systems that do not meet these standards will be shut down. This is the essence of human-centric, trustworthy AI.”

Jeremy Foote, a computational social scientist studying cooperation and collaboration in online communities, said, “People are incredibly creative at finding ways to express and expand their agency. It is difficult to imagine a world where they simply relinquish it. Rather, the contours of where and how we express our agency will change, and new kinds of decisions will be possible. In current systems, algorithms implement the goals of their designers. Sometimes those goals are somewhat open-ended, and often the routes that AI/ML systems take to get to those goals are unexpected or even unintelligible. However, at their core, the systems are designed to do things that we want them to do, and human agency is deeply involved in designing the systems, selecting parameters and pruning or tweaking them to produce outputs that are related to what the designer wants.”

Jon Lebkowsky, CEO, founder and digital strategist at Polycot Associates, wrote, “At levels where AI is developed and deployed, I believe there’s an understanding of its limitations. I believe that the emphasis going forward, at least where decisions have critical consequences, will be on decision support vs. decision-making. Anyone who knows enough to develop AI algorithms will also be aware of how hard it is to substitute for human judgment. I submit that we really don’t know all the parameters of ‘good judgment,’ and the AI we develop will always be limited in the ability to grasp tone, nuance, priority, etc. We might be able to effectively automate decisions about market selection, cosmetics, program offerings (but less so selection), etc. But consequential decisions that impact life and health, that require nuanced perception and judgment, will not be offloaded wholly to AI systems, however much we depend on their support. The evolution of digital tech’s ‘broadening and accelerating rollout’ will depend on the evolution of our sophistication about and understanding of the technology. That evolution could result in disaster in cases where we offload the wrong kinds of decisions to autonomous technical systems.”

Robert D. Atkinson, founder and president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, said, “In terms of risks to human autonomy, we should not be very concerned. Technology always has been a tool that humans controlled, and there is no reason to believe otherwise going forward. To the extent autonomous decision-making systems make important decisions, they will 1) on average be more accurate and timely decisions than humans make (or else they wouldn’t be used); 2) in most cases they will be able to be overridden by humans. If a company or other organization implements such a system and it does not improve people’s lives, the company will not be able to sell the system because people will not use it.”

Melissa R. Michelson, dean of arts and sciences and professor of political science at Menlo College, wrote, “The trend I see in terms of AI-assisted life is that AI makes recommendations, while humans retain ultimate control. While AI is likely to improve its ability to predict our needs by 2035, based on tracking of our behavior, there is still a need for a human to make final decisions, or to correct AI assumptions. In part, this is due to the inherent nature of human behavior: It is not always consistent or predictable, and AI is thus unable to always accurately predict what decision or action is appropriate to the moment. It is also due to the undermining of AI tracking that individuals engage in, either deliberately or unintentionally, as when they log in using another person’s account or share an email address, or when they engage in offline behavior. I expect that by 2035 there will be more automation of many routine activities, but only at the edges of our daily lives. Complex activities will still require direct human input. A shortcoming of AI is the persistent issue of racism and discrimination perpetuated by processes programmed under a system of white supremacy. Until those making the programming decisions become anti-racists, we will need direct human input to control and minimize the harm that might result from automated systems based on programming overwhelmingly generated by white men.”

Chris Labash, associate professor of communication and innovation at Carnegie Mellon University, wrote, “It’s not so much a question of ‘will we assign our agency to these machines, systems and bots?’ but ‘ what will we’ assign to them? If, philosophically, the best decisions are those based on intelligence and humanity, what happens when humanity takes a back seat to intelligence? What happens when agency gives way to comfort? If you are a human without agency, are you still human?’ The data I have read suggests that our future won’t be so much one where humans will not have agency, but one where humans offload some decisions to autonomous and artificial intelligence. We already trust making requests to bots, automated intelligence and voice assistants, and this will only increase. Five years ago a 2018 PwC study on voice assistants indicated that usage, trust and variety of commands were increasing, and customer satisfaction was in the 90% range. There is likely to be a considerable broadening of dependence on decisions by autonomous and artificial intelligence by 2035. My guess is although many important decisions will be made by autonomous and artificial intelligence, they will be willingly delegated to non-human intelligence, but we will still keep the decision of what decisions to offload to ourselves.”

Steve Sawyer, professor of information studies at Syracuse University, wrote, “We are bumping through a great deal of learning about how to use data-driven AI. In 15 years, we’ll have much better guidance for what is possible. And the price point for leveraging AI will have dropped — the range of consumer and personal guidance where AI can help will grow.”

Several said the trend will continue toward broader use of publicly accepted autonomous decisions.

Sam Lehman-Wilzig, author of “ Virtuality and Humanity” and professor at Bar-Ilan University, Israel, said, “On the micro, personal level, AI ‘brands’ will be competing in the marketplace for our use — much like Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok compete today — designing their AI ‘partners’ for us to be highly personalized, with our ability to input our values, ethics, mores, lifestyle, etc., so that the AI’s personalized ‘recommendations’ will fit our goals to a large extent. But on the macro level humans will not be in charge of decisions/policy. Once we can be relatively assured that AI decision-making algorithms/systems have no more (and usually fewer) inherent biases than human policymakers we will be happy to have them ‘run’ society on the macro level — in the public sphere. There, AI-directed decisions will be autonomous; we will not be in control. Indeed, one can even posit that many (perhaps most) people throughout history have been perfectly happy to enable a ‘higher authority’ (God, monarch/dictator, experts, technocrats, etc.) to make important decisions for them (see Erich Fromm’s ‘ Escape from Freedom’).”

An author whose writing has focused on digital and post-digital humanity asked, “Is it clear that humans are in control even now? They are not in control on Wall Street, not in control over what they see on the internet, not in control piloting airplanes, not in control in interacting with customer service of corporate providers of everyday services, etc.

“

Are we in a period of coevolution with these systems and how long might that last? Humans do better with AI assistance. AI does better with human assistance. The word ‘automation’ sounds very 20th century. It is about configuring machines to do something that humans formerly did or figured out they could do better when assisted by the strength, precision or predictability of machines. Yet the more profound applications of AI already seem to be moving toward the things that human beings might never think of doing.

“

Could even the idea of ‘decisions’ eventually seem dated? Doesn’t adaptive learning operate much more based on tendencies, probabilities, continual refactorings, etc.? The point of coevolution is to coach, witness and selectively nourish these adaptions. By 2035 what are the prospects of something much more meta that might make Google seem as much an old-fashioned industry as it itself once did to Microsoft?

“

This does not imply the looming technological singularity as popular doomsayers seem to expect. Instead, the drift is already on. Like a good butler, as they say, software anticipates needs and actions before you do. Thus, even the usability of everyday software might be unrecognizable to the expectations of 10 years ago. This is coevolution.

“

Meanwhile Google is feeding and mining the proceedings of entire organizations. For instance, in my university, they own the mail, the calendars, the shared documents, the citation networks and ever more courseware. In other words, the university is no longer at the top of the knowledge food chain. No humans are at the top. They just provide the feed to the learning. The results tend to be useful. This, too, is coevolution.”

Brad Templeton, internet pioneer, futurist and activist, chair emeritus of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, wrote, “The answer is both. Some systems will be designed for more individual agency, others will not. However, absent artificial general intelligence with its own agency, the systems which make decisions will be designed or deployed by some humans according to their will, and that’s not necessarily the will of the person using the system or affected by the system. This exists today even with human customer-service agents, who are given orders and even scripts to use in dealing with the public. They are close to robots with little agency of their own — which is why we always want to ‘talk to a supervisor’ who has agency. Expect the work of these people to be replaced by AI systems when it is cost-effective and the systems are capable enough.”

A number of the experts responding here made the argument that issues tied to this question will likely be battlegrounds in the future as human autonomy is debated. They asked, “What elements define human agency?” They noted that even small-scale decisions such as where people meet, how they move from place to place or how they might complete a written sentence can be consequential. They also said there are vastly varied points of view in regard to how and when human intervention in automated decision-making should be exercised. Some predicted these kinds of subtle issues will produce strong debates about what people should outsource to tech and what should be preserved as the essential domains in which humans should decide for themselves. Here is how one respondent tackled this:

Henry E. Brady, professor and former dean of the school of public policy, University of California, Berkeley, wrote, “My sense is that there will be a tremendous demand for having methods that will ensure that most important decisions are curated and controlled by humans. Thus, there will be a lot of support, using AI, text-processing and other methods, and there will be ways developed to control these processes to ensure that they are performing as desired.

“

One of the areas in which I expect a lot of work will be done is in precisely defining ‘key decisions.’ Clearly there is already a recognition that bail, parole and other decisions in the criminal justice system are key decisions that must be approached carefully to avoid bias. Even for decisions that are less key, such as using a dating app or Uber, there is a recognition that some features are key: There must be some security regarding the identity of the parties involved and their trustworthiness. Indeed, developing trustworthy methods will be a major growth industry.

“

One of the trade-offs will be allowing a broader range of choices and opportunities versus verifying the authenticity of these as real choices that can deliver what they promise. So far technology has done a better job of broadening choices than assuring their authenticity. Hence the need for methods to ensure trustworthiness.”

This is a nonscientific canvassing, based on a nonrandom sample. The results represent only the opinions of the individuals who responded to the queries and are not projectable to any other population.

In the next section, we highlight the remarks of experts who gave some of the most wide-ranging yet incisive responses to our request for them to discuss human agency in digital systems in 2035. Following, we offer a set of longer, broader essays written by leading expert participants. And that is followed with additional sections covering respondents’ comments organized under the sets of themes set out in the tables above. The remarks made by the respondents to this canvassing reflect their personal positions and are not the positions of their employers. The descriptions of their leadership roles help identify their background and the locus of their expertise. Some responses are lightly edited for style and readability.

What ChatGPT has to say about AI and the future of human agency

ChatGPT is an AI-powered chatbot that was released to the general public by its inventors at OpenAI in November 2022, several months after we canvassed technology experts about the future of human agency. It was programmed on large datasets of human writing with the goal of producing human-like responses to people’s prompts or questions. It immediately attracted broad public attention and has drawn a considerable amount of commentary about its effectiveness, its possible use cases and its potential impact on key parts of society. Early testing of the chatbot’s integration into Microsoft’s Bing search engine also created examples that distressed and spooked users.

To see how ChatGPT might address the issues covered in this report, we asked it to write “three conversational paragraphs with examples” in response to this question: By 2035, will smart machines, bots and systems powered by artificial intelligence be designed to allow humans to easily be in control of most tech-aided decision-making that is relevant to their lives? Why do you think humans will or will not be in control of important decision-making in the year 2035?

ChatGPT’s answer:

“

Yes, it is highly likely that by 2035, smart machines, bots, and AI systems will be designed to allow humans to easily control important tech-aided decision-making in their lives. As AI technology continues to advance, it will be important for developers to prioritize user control and transparency in their AI systems. This could include features such as adjustable privacy settings, the ability to explain AI decisions and recommendations, and the option for human overrides.

“

An example of this trend can already be seen in the development of voice assistants, such as Amazon’s Alexa or Google Home. These devices were designed to allow users to control their home environment with voice commands, but they also give users the ability to adjust their privacy settings and control what information is shared with the AI system. This type of user control is becoming increasingly important as AI is integrated into more aspects of our lives and decision-making.

“

However, it is possible that some AI systems may not prioritize human control in the future. For example, in certain industries, AI systems may be designed to make autonomous decisions without human intervention for efficiency or safety reasons. In these cases, it will be important for developers to ensure that these AI systems are transparent in their decision-making and include oversight mechanisms to ensure that they are acting ethically. Overall, the extent to which humans will be in control of AI-powered decision-making will depend on the values and priorities of AI developers and the regulations put in place to govern AI use.”

- Answer generated on Feb. 1, 2023

Originally published at https://www.pewresearch.org on February 24, 2023.

APPENDIX

How we did this

This report covers results from the 15th “Future of the Internet” canvassing that Pew Research Center and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center have conducted together to gather expert views about important digital issues.

This is a nonscientific canvassing based on a nonrandom sample; this broad array of opinions about the potential influence of current trends may lead between 2022 and 2035 represents only the points of view of the individuals who responded to the queries.

Pew Research Center and Elon’s Imagining the Internet Center sampled from a database of experts to canvass from a wide range of fields, inviting entrepreneurs, professionals and policy people based in government bodies, nonprofits and foundations, technology businesses and think tanks, as well as interested academics and technology innovators.

The predictions reported here came in response to a set of questions in an online canvassing conducted between June 29 and Aug. 8, 2022.

In all, 540 technology innovators and developers, business and policy leaders, researchers and activists responded in some way to the question covered in this report.

More on the methodology underlying this canvassing and the participants can be found in the section titled “About this canvassing of experts.”

Names mentioned (selected, first one listed)

- Alf Rehn,

- Barry Chudakov

- Kathryn Bouskill,

- Greg Sherwin,

- J. Nathan Matias

- Alan Mutter,

- Christopher W. Savage,