NEJM

Véronique Bouvard, Ph.D., Nicolas Wentzensen, M.D., Ph.D., Anne Mackie, M.B., B.S., Johannes Berkhof, Ph.D., Julia Brotherton, M.D., Ph.D., Paolo Giorgi-Rossi, Ph.D., Rachel Kupets, M.D., Robert Smith, Ph.D., Silvina Arrossi, Ph.D., Karima Bendahhou, M.D., M.P.H., Karen Canfell, D.Phil., F.A.H.M.S., Z. Mike Chirenje, M.D., et al.

In May 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) called for a global initiative to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem.

To achieve this goal, global scale-up of effective vaccination against the human papillomavirus (HPV) as well as screening for and treatment of cervical cancer are required.

Cervical cancer screening was evaluated in 2005 by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Handbooks program,1 and a reevaluation was deemed to be timely given the major advances in the field since then.

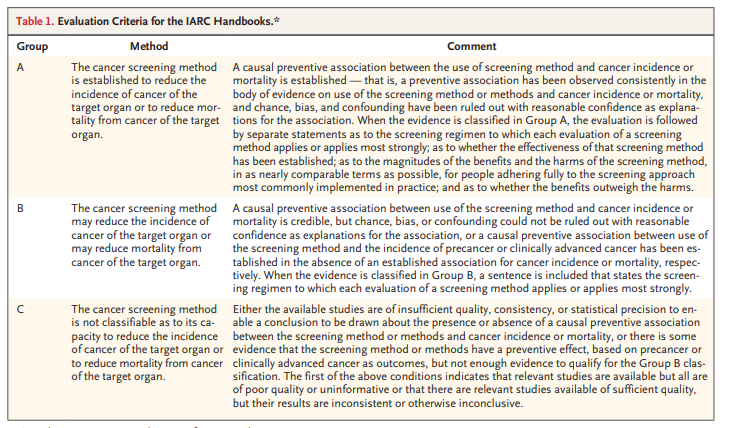

The new handbook provides updated evaluations of the effectiveness of screening methods, which were used as a basis for the update of the WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention.2 We convened an IARC Working Group of 27 scientists from 20 countries to assess the evidence on the current approaches to and technologies used in cervical cancer screening with the use of the newly updated Handbooks Preamble3 (Figure 1) and Table 1).

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer and the second most common cause of death from cancer in women of reproductive age worldwide.4 The highest incidence and mortality rates are generally observed in countries with the lowest values on the Human Development Index5; these rates also correlate with a high prevalence of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).6

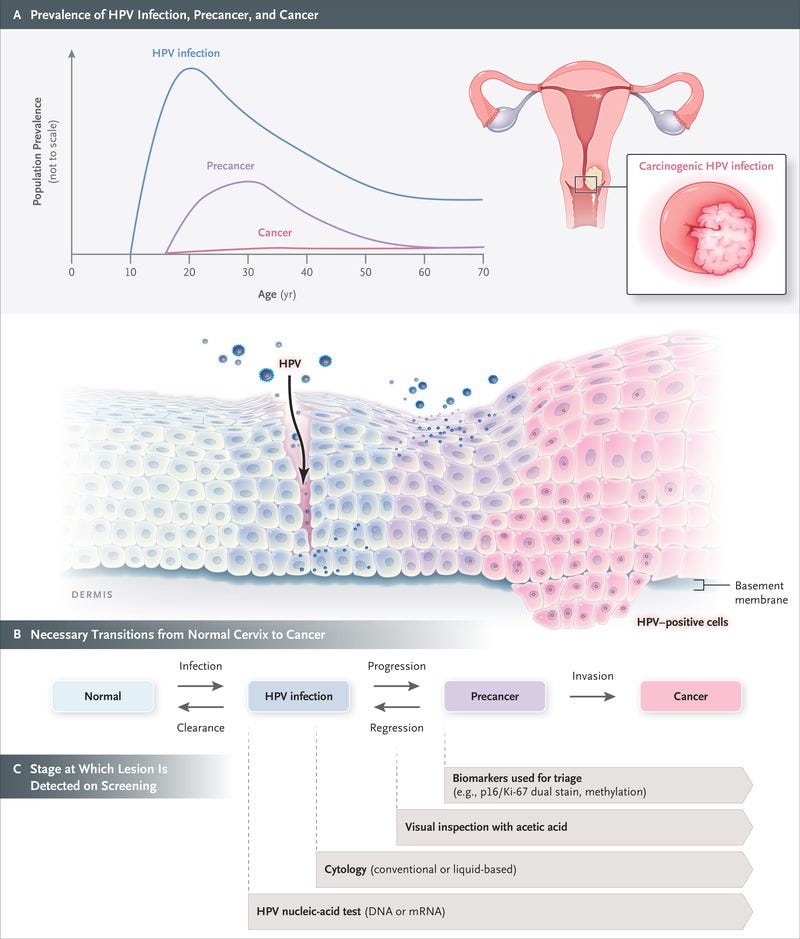

Figure 2.

Schematic Representation of the Natural History of Cervical Cancer.

The natural history of cervical cancer is well understood, and a multistep carcinogenesis model is widely accepted, with HPV infection, progression to precancer, and invasion to cancer viewed as critical steps (Figure 2). Cervical cancer is largely preventable through both vaccination and screening for precursor lesions, with appropriate follow-up and treatment.7 As a secondary objective, screening may lead to early detection of cancer, which may allow for earlier treatment and a reduction in the risk of death from cervical cancer. The prevention of cervical cancer and death through screening typically relies on a multistep process that includes screening, triage of patients with positive results on screening, confirmation on biopsy, and treatment of patients with precancerous lesions. Delivery of screening and treatment is available in many countries through programs that are population based (organized) or nonpopulation based (unorganized) or through opportunistic screening; settings with limited resources may adopt a screen-and-treat approach (testing immediately followed by treatment, without confirmation on biopsy). Participation rates and coverage vary widely across countries and settings.8 The main determinants of participation are socioeconomic status, ethnic group, health insurance status, and education level; access to services may also be a problem for some women owing to a lack of power, authority, or control,9,10 which in some settings represent major barriers to participation.

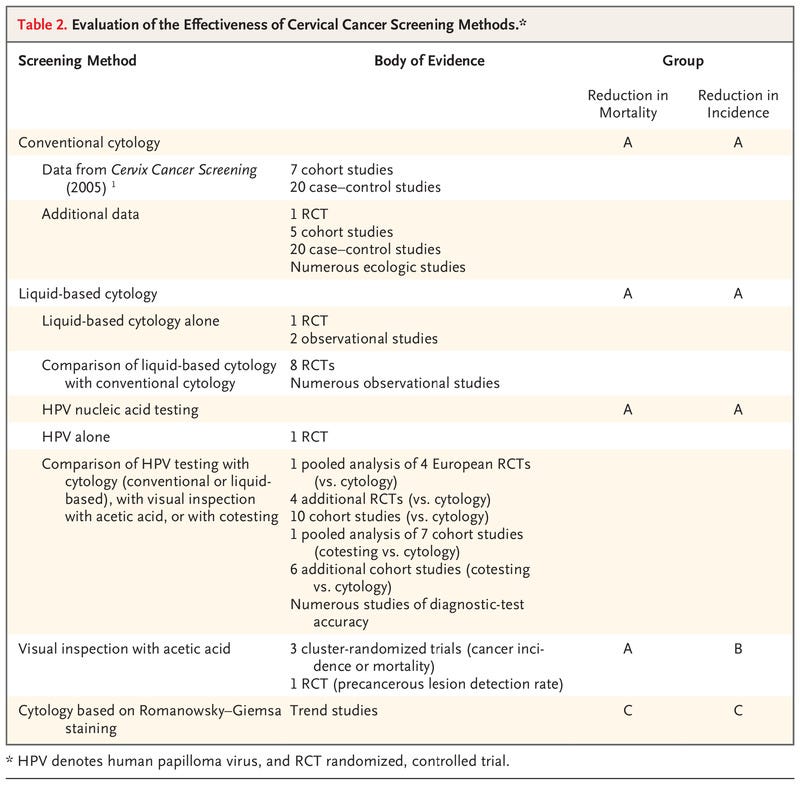

Table 2.

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Cervical Cancer Screening Methods.

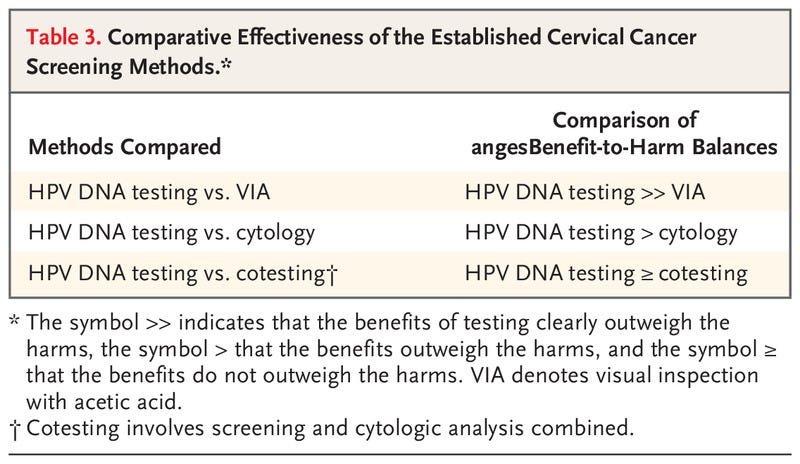

Table 3.

Comparative Effectiveness of the Established Cervical Cancer Screening Methods.

Although we remain cognizant that successful reduction in the incidence of cancer can occur only with appropriate follow-up and treatment of screen-positive women, the aim of this evidence review is to evaluate primary screening tests for their effectiveness in reducing the incidence of cervical cancer and the risk of death associated with cervical cancer. Postscreening components of care (i.e., management, including colposcopy, and treatment) and issues related to implementation have not been assessed; these topics are considered in the updated WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention.2 Here, we briefly summarize the scientific evidence reviewed by the Working Group and discuss the rationale and considerations that underlie the evaluations (Table 2) and the comparative statements (see Table 3). The full report will be published as part of the IARC series of handbooks on cancer prevention.11

Effectiveness of Screening

The Working Group reviewed and evaluated the evidence relative to the efficacy and effectiveness of screening by conventional cytology, liquid-based cytology, visual inspection with acetic acid, nucleic acid testing, and cytology based on Romanovsky–Giemsa staining. A summary of the evidence is presented below.

CONVENTIONAL CYTOLOGY

Cervical cytologic analysis (Papanicolaou testing) was widely introduced as a screening test during the 20th century without having been assessed in randomized, controlled trials. The previous IARC Handbook on cervical cancer screening (2005)1 identified 7 cohort studies and 20 case–control studies conducted in multiple countries and concluded that there was sufficient evidence that screening by conventional cytology had reduced the incidence of and mortality associated with cervical cancer. Since then, a randomized, controlled trial12,13 and numerous population-based observational studies (5 cohort studies and 20 case–control studies) conducted in multiple countries and settings have compared the incidence of cervical cancer and mortality among women who were screened with those among women who were not screened.14 This body of evidence is supported by ecologic data on the incidence of cervical cancer and on the mortality associated with cervical cancer from population-based registries obtained after the introduction or expansion of cytologic screening. The aggregate evidence from all sources shows that the use of conventional cytologic analysis consistently reduces the incidence of and mortality associated with cervical cancer, with greater effects observed in organized screening programs. On the basis of these results, the Working Group confirmed the previous evaluation and concluded that screening with cytology is established to reduce the incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer (Group A). The Working Group, recognizing the subjective nature of the test and the strong need for appropriate training and systems to ensure and maintain high quality, noted that this evaluation applies to conventional cytologic screening performed within a quality-assured laboratory system with appropriate follow-up and treatment.

LIQUID-BASED CYTOLOGY

Eight randomized, controlled trials15–22 and numerous observational studies in a population-based, nationwide program have compared the accuracy of liquid-based and conventional cytologic analysis. The studies were conducted in settings that use cytologic analysis as a stand-alone, first-level test, with different strategies of referral for colposcopy. Overall, as compared with conventional cytologic analysis, liquid-based cytologic analysis had a similar or higher sensitivity for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) of grade 2 or higher (CIN2+) and grade 3 or higher (CIN3+), a similar or lower specificity and positive predictive value, and a lower proportion of unsatisfactory slides. In addition, one randomized, controlled trial18 and two observational studies in which the longitudinal outcomes of liquid-based cytologic analysis were assessed showed that there was a good correlation between the baseline detection rate and reduced incidence of CIN2, CIN3, and invasive cancers in subsequent screening rounds. On the basis of the similar performance of liquid-based cytologic analysis and conventional cytologic analysis, the Working Group extended the previous evaluation and concluded that screening with liquid-based cytology reduces the incidence of and the mortality associated with cervical cancer (Group A).

VISUAL INSPECTION WITH ACETIC ACID

Three population-based, cluster-randomized intervention trials conducted in India assessed the effectiveness of visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) as compared with no screening in reducing the incidence of or mortality associated with cervical cancer.13,23,24 In two of the three trials, there was a consistent and significant reduction in mortality as compared with no screening after a single round13,23 or multiple rounds24 of VIA screening. A reduction in mortality may have resulted from the detection and treatment of precancerous lesions, the downstaging of invasive cervical cancer (i.e., a shifting of the stage distribution of cancers detected toward a lower stage), or both. The reduction in the incidence of cervical cancer after VIA screening was observed in only one of the three randomized trials.23 In addition, a smaller randomized, controlled trial conducted in a “screen-and-treat” setting in South Africa showed a reduction in the detection of CIN2+ 6 months after VIA screening as compared with the control (standard care).25 On the basis of these results, the Working Group updated the previous evaluation and concluded that VIA is established to reduce the mortality associated with cervical cancer (Group A) and may reduce the incidence of cervical cancer (Group B). The Working Group, recognizing the subjective nature of the test, noted that this evaluation applies to VIA screening implemented with the use of quality assurance, performed by well-trained health care workers, and conducted with appropriate follow-up and treatment.

HPV NUCLEIC ACID TESTING

A single randomized, controlled trial conducted in India13 evaluated thebeneficial effects among women of nucleic acid testing for high-risk HPV genotypes as compared with no screening on the mortality associated with cervical cancer and showed that a single round of screening reduced mortality by nearly half. All other available studies relied on the comparison of HPV testing with cytologic analysis, VIA, or both. In a pooled analysis of four European randomized trials, HPV testing led to a greater reduction in the incidence of cervical cancer than did cytologic analysis.26 Furthermore, numerous cohort studies conducted in screening settings, as well as diagnostic-test accuracy studies that compared HPV testing (including HPV DNA and mRNA testing) with cytologic analysis, VIA, or both, showed that HPV testing is more effective in detecting cervical precancers and in subsequently reducing the incidence of cervical cancer as compared with other screening approaches. On the basis of these results, the Working Group extended a previous evaluation and concluded that HPV nucleic acid testing is established to reduce the incidence of and mortality associated with cervical cancer (Group A).

CYTOLOGY BASED ON ROMANOWSKY–GIEMSA STAINING

Romanowsky–Giemsa staining has been used for a long time to stain many types of cytologic specimens. It remains in use in some states of the former Soviet Union in screening for cervical cancer because of the lower costs of a single examination and the wider availability of materials as compared with Papanicolaou staining. However, no comparative study on the accuracy, efficacy, or effectiveness of the technique in cervical cancer screening was available to the Working Group. Furthermore, data on the screening performance of programs adopting this method suggest low reproducibility and low specificity.27–29 On the basis of this information, the Working Group concluded that screening with cytology based on Romanowsky–Giemsa staining is not classifiable as to its capacity to reduce the incidence of or the mortality from cervical cancer (Group C).

Balance of Benefits and Harms

The benefits of cervical cancer screening outlined above need to be balanced against possible harms.

All the screening methods reviewed may cause pain or discomfort during examination or sample collection30; self-sampling (collection of the sample by the woman herself) for HPV testing may reduce discomfort.31 Screening for cervical cancer may also generate anxiety related to the screening procedure itself, the receipt of results, and any subsequent diagnostic and treatment pathways. A positive result is associated with increased levels of anxiety and distress and may arouse concerns about cancer; it may also trigger feelings of stigma and shame, particularly after a positive HPV test result.32 Potential physical harms associated with subsequent diagnostic procedures and treatment include risks of bleeding, infection, and adverse obstetric outcomes.33 A common measure of harm is the rate of referral to colposcopy and treatment. Tests with higher proportions of false positive or unsatisfactory results are associated with additional potential harms, such as increased costs to patients, loss to follow-up, and loss of confidence in the service.

Overall, the Working Group concluded that the benefits of screening with HPV nucleic acid testing or with cytologic analysis outweigh the harms for women 30 years of age or older.

There is less certainty regarding the value of either technique for women younger than 30 years of age, especially when triage testing of HPV-positive women is not in place.

With VIA, the benefits in terms of reduction in the incidence of and mortality associated with cervical cancer, as well as the harms related to false positive test results, are highly variable and observer-dependent; therefore, whether the benefits of VIA will consistently outweigh its harms is unclear.34

Overall, the Working Group concluded that the benefits of screening with HPV nucleic acid testing or with cytologic analysis outweigh the harms for women 30 years of age or older.

Comparison of Screening Methods

In addition to evaluating these screening methods separately, for each comparison for which evidence was available, the Working Group assessed the comparative effectiveness.

The relative benefits and harms as well as the balance of benefits and harms were considered.

HPV DNA TESTING AS COMPARED WITH CYTOLOGY

The effectiveness of HPV DNA testing has been compared with that of cytologic analysis (conventional or liquid based) in eight randomized, controlled trials involving routine settings in which screening for cervical cancer was provided35–44 (one of the trials involved a previously unscreened population13); in 10 cohort studies that used results from regional, national, and pilot primary HPV DNA screening programs; in six cohort studies in which cotesting (HPV DNA screening and cytologic analysis combined) was compared with cytologic analysis alone; in one pooled analysis of seven other such cohorts; and in numerous studies of the accuracy of diagnostic tests.

Overall, HPV DNA testing is more sensitive than cytologic analysis for the detection of CIN2+ and is associated with reduced detection rates of CIN2+ in subsequent screening rounds and with a greater reduction in the incidence of cervical cancer than cytologic analysis when the same screening interval is used.

The risk of CIN3+ over a period of 3 to 10 years is lower after a negative HPV DNA test result than after a negative cytologic test result.

Overall, the benefits of the greater reduction in the incidence of and mortality associated with cervical cancer outweigh the harms related to the increase (mainly in the first round) in positive results and colposcopy referrals and the potential increase in psychological harms observed with HPV DNA testing.

With the infrastructure permitting, the use of adequate triage tests can greatly reduce colposcopy referral rates while ensuring a high sensitivity for the detection of precancerous lesions.45

The balance is expected to be even more favorable after several rounds of HPV DNA–based screening, since HPV DNA testing allows for longer intervals between screenings than cytologic analysis.

HPV DNA TESTING AS COMPARED WITH VIA

Two randomized, controlled trials, three cross-sectional studies, and a pooled analysis of two cohorts have been conducted to assess the effectiveness of HPV DNA testing as compared with that of VIA in cervical cancer screening.12,13,25,46–50

Overall, a greater number of high-grade cervical lesions (CIN2+, CIN3+, or both) were detected with HPV DNA testing.

In randomized trials, as compared with VIA, HPV DNA testing led to a greater reduction in detection rates of CIN2+ at both 6 months25 and 36 months46 and to a greater reduction in cervical cancer of stage II or higher and in mortality associated with cervical cancer.12,51

Because of the high variability of VIA, the test positivity was inconsistent across studies, and the respective harms associated with the methods could not be compared.

Thus, HPV DNA testing results in greater benefits than VIA, and these benefits outweigh the potential increase in both true and false positive results.

VIA has other substantial limitations, such as subjectivity, heterogeneity, and potential misclassification of outcomes.

HPV DNA TESTING ALONE AS COMPARED WITH COTESTING

Cotesting is defined as simultaneous HPV DNA testing and cytologic testing conducted with the use of the same sample.

The comparative effectiveness of HPV DNA testing alone and cotesting has been assessed in numerous studies, including a meta-analysis52 of three randomized, controlled trials.53–55

The studies spanned nearly 15 years and differed regarding the referral strategies used, the follow-up time established, and the outcomes examined (CIN2+, CIN3+, and invasive cancer).

As compared with HPV DNA testing alone, there is a minimal increase in sensitivity and a lower specificity for the detection of CIN2+ and CIN3+ with cotesting, which has led to an increase in referrals for colposcopy and possibly treatment and a decrease in positive predictive value in referred women (increased detection of regressive lesions).

The difference in sensitivity affects very few cases, which suggests that the effect of the cytologic component of cotesting is very limited and that the effect on cancer incidence is unclear.56

Furthermore, over a longer follow-up period, the cumulative risks of CIN2+ and CIN3+ differ minimally between women with cotest-negative results and women with HPV-negative results.57

The benefits of cotesting do not outweigh the harms.

Considerations Regarding the Evaluation

Several approaches to cervical cancer screening were classified in Group A. Considerations as to which technology to implement include test performance and factors such as reproducibility, barriers to implementation, scalability, and cost, among others.2

Cytology is effective and is still widely used. However, it is prone to subjective assessment and lacks reproducibility.

Conventional cytologic analysis may result in a large proportion of unsatisfactory slides; in contrast, liquid-based cytologic analysis overcomes some of these quality issues and provides the opportunity to perform both molecular and cytologic tests with a single sample (e.g., both when HPV testing is used for triage of atypical or mildly abnormal cytologic analysis and when cytologic analysis is used for triage of HPV-positive women).

As compared with HPV-based screening, cytologic screening requires more frequent testing and thus a greater number of tests over a lifetime to achieve the same reduction in cancer incidence.

In addition, cytologic analysis cannot be conducted on patient-collected specimens.

Thus far, owing to its low cost, low infrastructure requirements, and potential to reduce loss to follow-up in screen-and-treat approaches, VIA has been implemented in resource-constrained settings and countries with limited access to health care.

However, the evidence that VIA reduces the incidence of cervical cancer is weak. In addition, proper training is needed to implement VIA screening, and harmonized interpretation criteria still need to be defined.

In settings that have implemented VIA-based screening, the transition to HPV testing will accelerate the reduction in the cancer burden.

HPV detection involves an objective molecular test.

As mentioned, HPV testing allows for longer intervals between screenings than cytologic analysis. HPV DNA testing can also be performed on vaginal samples that women collect themselves, an approach that extends access to screening to underserved populations.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 56 studies of diagnostic-test accuracy58 and several additional, more recent studies59–62 have shown that as compared with tests performed with the use of cervical samples collected by a clinician, tests performed with the use of vaginal samples collected by women themselves can achieve a similar sensitivity and specificity for the detection of CIN2+ or CIN3+ when polymerase-chain-reaction assays are used for the detection of HPV but not when signal amplification or HPV mRNA tests are used.

HPV mRNA testing has been shown to have similar cross-sectional sensitivity and higher specificity than HPV DNA testing for the detection of CIN3+, but evidence regarding longitudinal outcomes is limited.

Although a negative HPV mRNA test indicates a lower risk of CIN2+ over a period of 3 years than a negative result on cytologic analysis,63–66 it is not clear whether the beneficial effect is equivalent to that of a negative result on an HPV DNA test.

It is important to use triage when determining which HPV-positive women need colposcopy, which need treatment, and which need both.

Triage helps to maximize the benefits of cervical screening and to limit the harms, and it can have a substantial effect on the performance of a screening program.

There are several triage strategies, each of which is associated with different performance characteristics. They include the use of genotyping for HPV16/18, cytologic analysis, p16/Ki67 dual staining, colposcopy, VIA, and combinations thereof.2,45

The age at which screening is started or stopped varies in programs around the world.

The Working Group did not evaluate the best age at which screening should be started or stopped.

The appropriate starting age may depend on the natural history of HPV infections in a population, the duration and coverage of the vaccination program, and other factors.

The Working Group noted that the screening of older women (i.e., ≥65 years of age) with the use of cytologic (conventional or liquid-based) analysis or HPV testing may continue to be effective, particularly in women without a history of regular normal screens.67

Special consideration is required when screening women living with HIV, since they are at increased risk for HPV infection, precancerous cervical lesions, and cancer, particularly women who have a history of immunosuppression.6,68,69

Therefore, in settings in which there is a high prevalence of HIV (e.g., in sub-Saharan Africa), a screen-and-treat approach based on the results of an HPV test may lead to substantial overtreatment.

On the basis of the scant evidence available on screening in this population, the WHO suggests using an HPV DNA primary screening test, with triage of HPV-positive women; triage may reduce the proportion of test-positive women for whom referral and treatment are warranted.70–72

Both overtreatment and undertreatment may occur when VIA is used to screen women living with HIV. Whereas there can be many false positive results, VIA may not detect precancerous lesions that are at high risk for progression.

Although several methods currently used in screening are effective in reducing the incidence of and the mortality associated with cervical cancer, HPV testing alone is the most effective given its balance of benefits and harms.

It is noteworthy that most of the evidence used to inform these evaluations comes from high-income settings, whereas the burden of disease and death is highest in low-resource settings, where data are scant.

Even when interventions that have been established to be effective are used, successful prevention of cervical cancer requires quality-assured health systems that can provide adequate follow-up, including triage when necessary, and appropriate treatment for women with positive screens, all of which can pose major challenges in resource-limited settings.73

Alongside the scaling up of HPV vaccination and cancer treatment, increasing global levels of screening and treatment will bring the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem within reach.

Supported by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, the American Cancer Society, and the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer.

Originally published at https://www.nejm.org.

About the authors

Véronique Bouvard, Ph.D., Nicolas Wentzensen, M.D., Ph.D., Anne Mackie, M.B., B.S., Johannes Berkhof, Ph.D., Julia Brotherton, M.D., Ph.D., Paolo Giorgi‑Rossi, Ph.D., Rachel Kupets, M.D., Robert Smith, Ph.D., Silvina Arrossi, Ph.D., Karima Bendahhou, M.D., M.P.H., Karen Canfell, D.Phil., F.A.H.M.S., Z. Mike Chirenje, M.D., Michael H. Chung, M.D., M.P.H., Marta del Pino, M.D., Ph.D., Silvia de Sanjosé, M.D., Ph.D., Miriam Elfström, Ph.D., Eduardo L. Franco, M.P.H., Dr.P.H., Chisato Hamashima, M.D., Dr.Med.Sc., Françoise F. Hamers, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., C. Simon Herrington, D.Phil., F.R.C.P., F.R.C.P.E., F.R.C.Path., Raúl Murillo, M.D., M.P.H., Suleeporn Sangrajrang, Ph.D., Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan, M.D., Mona Saraiya, M.D., M.P.H., Mark Schiffman, M.D., M.P.H., Fanghui Zhao, M.D., Ph.D., Marc Arbyn, M.D., Ph.D., Walter Prendiville, F.R.C.O.G., Blanca I. Indave Ruiz, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., Isabel Mosquera‑Metcalfe, Ph.D., and Béatrice Lauby‑Secretan, Ph.D.

Author Affiliations

From the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon (V.B., W.P., B.I.I.R., I.M.M., B.L.-S.), and the National Public Health Agency, Saint-Maurice (F.F.H.) — both in France; the National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD (N.W., M. Schiffman); Public Health England and Screening, London (A.M.); Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam (J. Berkhof); VCS Foundation, Melbourne, VIC (J. Brotherton), Australia; Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale — IRCCS Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy (P.G.R.); the University of Toronto, Toronto (R.K.); the American Cancer Society (R. Smith), Emory University (M.H.C.), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (M. Saraiya) — all in Atlanta; the Center for the Study of the State and Society, and the National Scientific and Technical Research Council — both in Buenos Aires (S.A.); the Casablanca Cancer Registry, Casablanca, Morocco (K.B.); The Daffodil Centre, a joint venture between the Cancer Council NSW and the University of Sydney, King’s Cross, NSW, Australia (K.C.); the University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences, Harare (Z.M.C.); Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona (M.P.); PATH, Seattle (S. de Sanjosé); Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm (M.E.); McGill University, Montreal (E.F.); Teikyo University, and the National Cancer Center — both in Tokyo (C.H.); the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh (C.S.H.); Hospital Universitario San Ignacio, Bogota, Colombia (R.M.); the National Cancer Institute, Bangkok, Thailand (S. Sangrajrang); Research Triangle Institute International, New Delhi, India (R. Sankaranarayanan); Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing (F.Z.); and Sciensano, Brussels (M.A.).

Dr. Lauby-Secretan can be reached at secretanb@iarc.fr or at the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Evidence Synthesis and Classification Branch, IARC Handbooks Program, 150 Cours Albert Thomas, 69372 Lyon CEDEX 8, France.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

Cervical Cancer Screening

View summary report as HTML or PDF View French version of The NEJM summary (hosted by Centre Léon Bérard) Read IARC…publications.iarc.fr