Health & Care Transformation (HCT)

Joaquim Cardoso MSc*

Chief Strategy Officer, Researcher and Editor

November 9, 2022

*MSc from London Business School — MIT Sloan Masters Program

Source: StatNews

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (full version)

“The tipping point is coming’:

Unprecedented exodus of young life scientists is shaking up academia

StatNews

By Jonathan Wosen

Nov. 10, 2022; San Diego

Rayyan Gorashi is keeping her options open. After all, she’s still a second-year bioengineering Ph.D. student at UC San Diego, and there are so many careers to explore.

Patent law has been high up on her list ever since a class she took in college. There’s also regulatory affairs. Oh, and science publishing sounds interesting, too.

There are many jobs the 24-year-old can imagine doing. Well, except for one.

“I came into grad school knowing that I do not want to go into academia.

Sad as it is, it’s a tough system that doesn’t favor people who are not systemically privileged,” said Gorashi, the daughter of Sudanese immigrants, who makes just $36,000 a year. Rent for a discounted on-campus apartment eats up a third of that.

“When you try to calculate your hourly wage, it’s sub-minimum wage, which is just ridiculous,” she said. “I’ve fought enough in my life. I don’t want to continue doing that.”

“I came into grad school knowing that I do not want to go into academia. Sad as it is, it’s a tough system that doesn’t favor people who are not systemically privileged,”

She’s not alone.

Young life science researchers are leaving academia at unprecedented levels for lucrative jobs in the private sector.

Like Gorashi, many of them are entering graduate programs already knowing they don’t want to remain in academia long-term, making their time in the ivory tower a pit stop rather than a final destination.

… many of them are entering graduate programs already knowing they don’t want to remain in academia long-term, making their time in the ivory tower a pit stop rather than a final destination.

The data around this tectonic shift are loud and clear.

So were the many people STAT spoke with, from Ph.D. students to postdoctoral researchers to graduate program directors, labor economists, and hiring managers in the biopharma industry.

Students and postdocs lambasted a system they say exploits their long hours at the lab bench to advance the careers and renown of professors.

In return, they’re left powerless, overworked, and so underpaid that eking out a living is difficult if not outright impossible. But those critiques go back decades.

What has changed is that there’s now a booming biotech industry and private sector with a seemingly insatiable need for life science talent — and the willingness to offer six-figure salaries and benefits.

For many young researchers, the allure of these jobs is irresistible.

Problems that have percolated for years are now coming to a head.

Faculty are reporting that they’re struggling to hire postdocs, delaying research projects and pressuring universities to consider improving salaries and benefits as endowments are shrinking.

Faculty are reporting that they’re struggling to hire postdocs, delaying research projects and pressuring universities to consider improving salaries and benefits as endowments are shrinking.

Demands for change are coming from within the system as well.

Graduate students, postdocs, and tens of thousands of other academic workers within the University of California system voted overwhelmingly last week to grant their union the authority to call a strike as soon as Nov. 14 if their demands for higher wages and support for working parents aren’t met.

It’s a situation that has many experts and university leaders thinking hard about the long-term future of academic science.

For people like Dawn Eastmond, senior director of education and outreach at Scripps Research, the challenges are many, from transforming biomedical training to better meet the needs of trainees to keeping afloat a system built upon postdoc and graduate student labor.

… the challenges are many, from transforming biomedical training to better meet the needs of trainees to keeping afloat a system built upon postdoc and graduate student labor.

“The tipping point is coming,” Eastmond said.

“There are a lot of conversations happening about how we do this moving forward, because I don’t think it is sustainable the way that it’s being done currently.”

“There are a lot of conversations happening about how we do this moving forward, because I don’t think it is sustainable the way that it’s being done currently.”

‘Worker bees’

The roots of what is happening now run deep. More than 30 years ago — long before the biotech boom, talk of a postdoc shortage, or looming graduate student strikes — experts already saw trouble on the horizon.

Just ask Shirley Tilghman.

She knows it sounds odd to say now, but Tilghman never worried about funding her Princeton University lab as a young molecular biologist in the 1970s, when government grants were quite plentiful for scientists. But while serving on a 1991 committee tasked by the National Research Council with looking into the experiences of new faculty, she realized how much things had already changed.

“These young people, who are probably far more talented than me, weren’t just paranoid. They had reason to be concerned,” said Tilghman, who later served as Princeton’s president from 2001 to 2013. “There’s nothing, I think, more terrifying than thinking I can work really hard, I can have great ideas, I can get them down on paper brilliantly, and I still might not get funded.”

The problem? Too many people, too few dollars. Working on that first report, released in 1994, was so jarring that Tilghman led a second committee to better understand the underlying issues.

What they found was even more troubling. The number of life science graduate students and postdocs was exploding out of proportion with the number of available faculty positions.

The trend had been clear for decades. About 60% of life scientists who earned a Ph.D. in 1963–64 secured tenure within 10 years. That figure dropped to 54% for those who received degrees in the early 1970s. And among graduates in the mid ’80s, only 38% were tenured within a decade.

The result was a broken labor market, according to Georgia State University economist Paula Stephan, one built on a seductive but flawed promise to graduate students and postdocs — that these “worker bees” of academia would one day be rewarded for their toils with hives of their own.

“The system had such a big buy-in to this concept,” said Stephan, who worked alongside Tilghman on the report. “Faculty benefit a tremendous amount from it, and they delude themselves.”

That second report, released in 1998, ended with a slew of recommendations:

- Stop the unchecked growth of graduate programs.

- Give students accurate information about their career prospects.

- Fund fewer trainees through research grants and instead pivot to training grants and fellowships, which require academic institutions to track student diversity, quality of instructions, and employment outcomes.

Fourteen years later, Tilghman would make almost exactly the same recommendations in yet another report, now as part of an advisory committee to the director of the National Institutes of Health.

This time, she also argued that academic labs needed to add more permanent staff scientist positions with competitive salaries.

The benefits of doing so, Tilghman said, would be twofold. These positions would open up more research opportunities within academia. Plus, having staff scientists would give professors less reason to hold onto postdocs and graduate students for as long as possible.

The NIH has acted on some of these recommendations.

The agency now has research grants specifically aimed at early-career researchers, including Ph.D. students looking to leapfrog a postdoc and jump directly into starting their own lab. And many graduate students and postdocs funded by the NIH now routinely meet with their advisers to discuss both their short-term research progress and long-term career goals.

“We’ve been taking a number of steps,” said Michael Lauer, NIH deputy director for extramural research, “within the limited resources that we like every other federal agency has.”

But Tilghman’s sense is still that progress has been slow. In total, she has contributed to nearly 500 pages of reports and a number of articles on the topic, but most of the recommendations she and colleagues made have gone unheeded.

“Culture is the hardest thing to change,” she said. “This is about culture. It’s about a longstanding culture generated when there were more dollars than people. Suddenly, we had more people than dollars.”

Tilghman teamed up with a few concerned colleagues and started a nonprofit in 2015 to draw attention to the situation. They called the group Rescuing Biomedical Research.

It folded after a few years due to a lack of funding.

Exodus from the ivory tower

While Tilghman, Stephan, and others say that academia hasn’t changed much over the years, the decisions students are making certainly have.

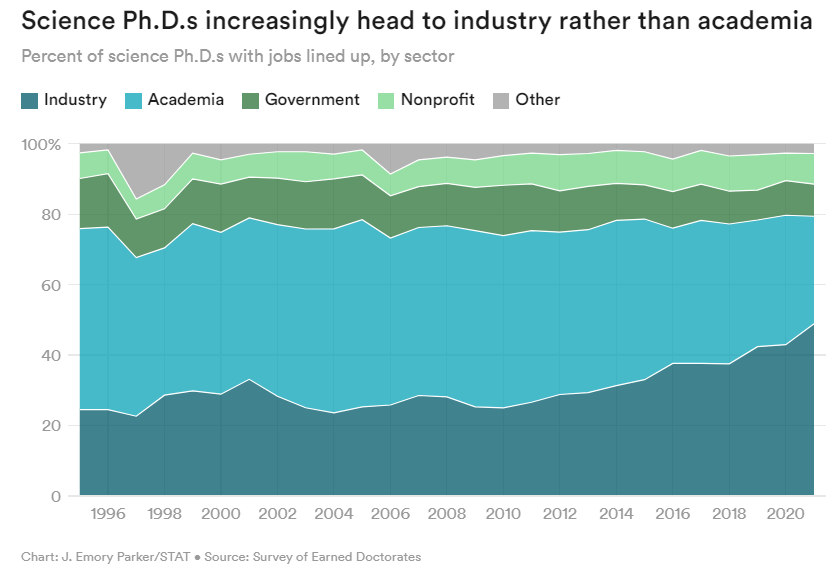

For much of the late 1990s and early 2000s, the proportion of newly minted life science Ph.D. graduates with jobs lined up who planned to go into industry hovered between 20% and 30%, according to the Survey of Earned Doctorates, an annual census conducted by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Meanwhile, graduates with job commitments who were academia-bound ranged from 40% to 50%.

That all changed about a decade ago. The percentage of industry-bound grads steadily rose, and, by 2019, eclipsed that of those going into academia for the first time — a trend that has only grown in the years since.

That all changed about a decade ago.The percentage of industry-bound grads steadily rose, and, by 2019, eclipsed that of those going into academia for the first time — a trend that has only grown in the years since.

The survey doesn’t spell out precisely what kinds of jobs students are taking, instead using “industry” as a catch-all term for any for-profit business and “academe” as a broad descriptor of all educational institutions.

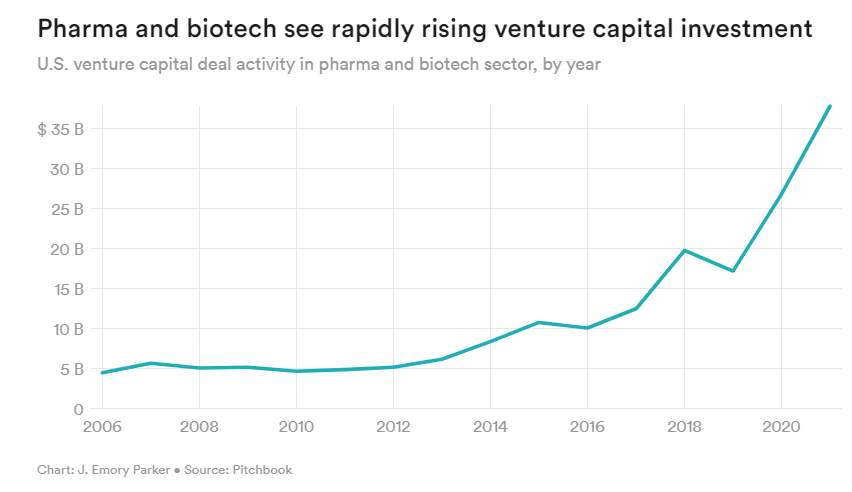

But the trend closely follows a sharp rise in dollars flowing into the biotech industry, with annual venture capital investments in pharma and biotech companies increasing from $5 billion in 2012 to $38 billion in 2021, according to Pitchbook.

And when life science companies raise heaps of cash, they hire quickly. Bay Area firm 10x Genomics is just one of many examples. The gene sequencing company, founded a decade ago, now employees 1,200 workers, nearly a third of whom have a Ph.D.

And when life science companies raise heaps of cash, they hire quickly. Bay Area firm 10x Genomics is just one of many examples. The gene sequencing company, founded a decade ago, now employees 1,200 workers, nearly a third of whom have a Ph.D.

“There’s an insatiable appetite for talent,” said co-founder Ben Hindson. “It doesn’t matter where you went to school. It doesn’t matter necessarily what you studied in your Ph.D. If you have an ability to learn, ability to get results and collaborate with others, I think you’ll fit in.”

“There’s an insatiable appetite for talent,” said co-founder Ben Hindson. “It doesn’t matter where you went to school. It doesn’t matter necessarily what you studied in your Ph.D. If you have an ability to learn, ability to get results and collaborate with others, I think you’ll fit in.”

The enthusiasm seems to go both ways. Graduate program directors have noticed an uptick in students expressing interest in non-academic careers near the start of their Ph.D. program — sometimes even when they’re still applying.

It wasn’t always like that, according to Eastmond, who ran Scripps Research’s graduate program from 2014 to 2021.

Leaving academia for industry was once seen as almost shameful, selling out.

“For quite some time, students didn’t want to be completely honest about what they want to do,” Eastmond said.

But that’s changed. Part of the reason may be that more incoming students have already worked in industry.

Life science students typically take a year or two after completing their bachelor’s before starting graduate school.

And Olivia Martinez, director of Stanford’s immunology program, has noticed more applicants who have spent that time working at companies rather than university labs.

And Olivia Martinez, director of Stanford’s immunology program, has noticed more applicants who have spent that time working at companies rather than university labs.

“They know they like it. It’s what they have seen,” she said. “That’s especially true around here,” given the Bay Area’s sprawling life science industry.

These jobs can expose young researchers to a new way to apply scientific knowledge and offer the challenge of transforming discoveries from publications into products.

They also offer money. Biomedical Ph.D. graduates entering industry can expect to make a median starting salary of $105,000, according to the Survey of Earned Doctorates, compared to $53,000 for a postdoc.

These jobs can expose young researchers to a new way to apply scientific knowledge and offer the challenge of transforming discoveries from publications into products.

They also offer money. Biomedical Ph.D. graduates entering industry can expect to make a median starting salary of $105,000, according to the Survey of Earned Doctorates, compared to $53,000 for a postdoc.

That’s roughly what Charlotte Lorenz and her husband each made when the pair joined the same UCSD neuroscience lab as postdocs in the fall of 2020. They got by the first year. But by the summer of 2021, their monthly rent spiked to nearly $3,000, and they had a second child. Pretty soon, they were paying more for rent, childcare, and taxes than they earned.

They cut back on everything except the bare essentials. They even tried walking an hour to and from daycare to avoid buying a car. When that failed, the couple burned through their savings. “I was pretty mad at that point,” said Lorenz.

The pair left UCSD for biotech earlier this year, and they haven’t looked back. But it’s not like they lost their love of the academic work. If they’d had affordable housing and free childcare, like in their native Germany, Lorenz said, they probably would have stayed.

The pair left UCSD for biotech earlier this year, and they haven’t looked back. But it’s not like they lost their love of the academic work. If they’d had affordable housing and free childcare, like in their native Germany, Lorenz said, they probably would have stayed.

Looming questions

Of course, not everyone is leaving academia. For many young researchers, an academic career embodies everything they love about science — a life dedicated to the pursuit of new truths about the dazzlingly complex world within and around us.

Of course, not everyone is leaving academia. For many young researchers, an academic career embodies everything they love about science — a life dedicated to the pursuit of new truths about the dazzlingly complex world within and around us.

That’s what excites Laura Rupprecht. As a Duke University postdoc, she’s deciphering how cells in our gut and brain communicate and shape our preference for certain foods. There’s nothing she’d rather do than one day run her own academic lab and search for new ways to manage conditions like obesity and diabetes.

That’s what excites Laura Rupprecht. As a Duke University postdoc, she’s deciphering how cells in our gut and brain communicate and shape our preference for certain foods. There’s nothing she’d rather do than one day run her own academic lab and search for new ways to manage conditions like obesity and diabetes. …“But the love of academia keeps me here.”

Rupprecht’s an optimist by nature, loves working with students, and, as she puts it, is kind of nerdy. She also thinks about quitting from time to time.

“There’s a bunch of startups and friends who are making a lot more money than me doing other scientifically related things, friends with Teslas and nice cars. And I think, ‘It must be nice,’” said Rupprecht, who lives in North Carolina’s Research Triangle, a bustling biotech hub. “But the love of academia keeps me here.”

Yet the overall shift of young researchers out of academia is already having real-world consequences.

Many faculty are having a harder time hiring postdocs, a trend first reported by Science and Nature earlier this year.

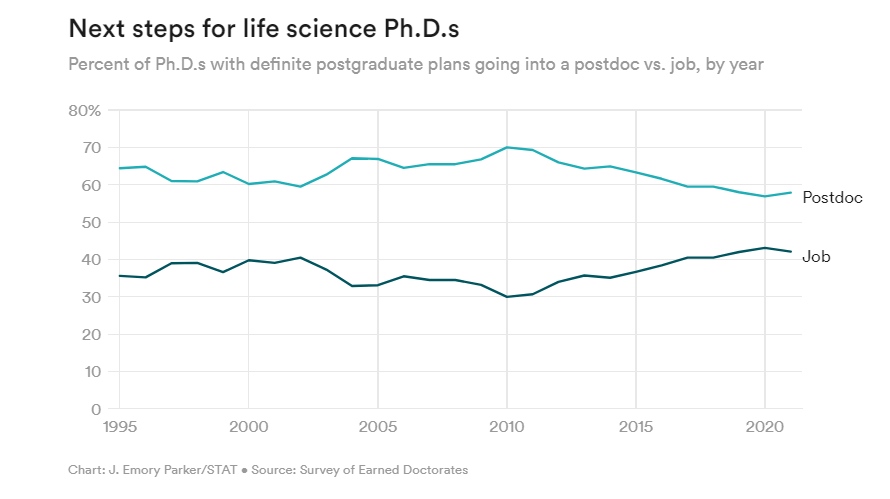

And Survey of Earned Doctorates data reviewed by STAT put hard numbers to this trend, showing that the fraction of life science graduates with concrete next steps who plan to do a postdoc has steadily dipped from 70% in 2010 to nearly 58% in 2021.

Yet the overall shift of young researchers out of academia is already having real-world consequences. Many faculty are having a harder time hiring postdocs, a trend first reported by Science and Nature earlier this year.

New faculty like Sara Zaccara are the hardest hit. In September, she joined Columbia University to start her own lab. For now, she is its only member.

Zaccara is looking to hire two postdocs. Failing to fill those slots could stall her research and endanger her chances of eventually getting tenure. But so far, qualified and experienced applicants have been hard to find.

That’s no surprise. Her research deals with one of the hottest fields in science — messenger RNA — and there’s no shortage of companies eager to scoop up talented scientists in this field. Zaccara herself turned down two industry job offers during her postdoc.

She has been trying to convince students to see a postdoc as an opportunity to build knowledge and skills regardless of their next career move. She has yet to win anyone over — even friends with Ph.D.s who’ve jumped straight into industry jobs.

While postdoctoral research is practically required for tenure-track positions in academia, there’s evidence it comes at a cost in other job sectors.

A 2017 study published in Nature Biotechnology found that it typically takes 15 years for researchers who did a biomedical postdoc to catch up to the salary of peers who entered the labor market with a Ph.D. alone.

A 2017 study published in Nature Biotechnology found that it typically takes 15 years for researchers who did a biomedical postdoc to catch up to the salary of peers who entered the labor market with a Ph.D. alone.

“Our hands are tied,” Zaccara said. “We cannot offer the salary of a company.”

There are signs entire institutions are being affected by these issues, too.

Eastmond says that Scripps now has 267 postdocs at its La Jolla campus compared with 609 a decade ago.

There are many reasons why, she adds, from faculty retiring to difficulty bringing in foreign researchers during the pandemic, but competing with industry is a factor, too.

There are signs entire institutions are being affected by these issues, too.

Eastmond says that Scripps now has 267 postdocs at its La Jolla campus compared with 609 a decade ago.

Scripps has taken in more graduate students to compensate.

Scripps has taken in more graduate students to compensate. That’s an imperfect fix, acknowledges Dennis Burton, chair of the institute’s immunology department, because postdocs are highly trained, already know how to work independently, and often help mentor Ph.D. students. Just a decade ago, there were many more postdocs than grad students in his lab, but now the opposite is true.

“It’s a disadvantage,” Burton said. “Postdocs do bring special qualities to a lab that are not easily replaced.”

As the famed research institute wrestles with this trend, Eastmond and others have also been involved in broader discussions around the future of graduate education.

And that means dealing with thorny questions:

- Should we even encourage students to do postdocs?

- Or can we move them directly into whatever career they want to go into?

- Should Ph.D. programs place more emphasis on practical skills students might need in the workforce, such as teamwork and negotiating?

And that means dealing with thorny questions: Should we even encourage students to do postdocs? Or can we move them directly into whatever career they want to go into? Should Ph.D. programs place more emphasis on practical skills students might need in the workforce, such as teamwork and negotiating?

And then there’s the question of how to pay people better.

MIT recently announced that it would bump its minimum postdoc salary from roughly $55,000 to $65,000 at the start of next year.

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital raised its starting postdoc salary to $70,000.

But while these increases have been well received, they’re still modest.

A first-year postdoc at the biotech company Genentech makes $86,000.

MIT recently announced that it would bump its minimum postdoc salary from roughly $55,000 to $65,000 at the start of next year.

A first-year postdoc at the biotech company Genentech makes $86,000.

For its part, the NIH will soon launch a working group focused on better understanding the postdoc shortage — what’s driving it, whether there have been measurable impacts on research productivity, and what NIH can do to better support postdocs.

The group will offer initial recommendations to the agency’s director in June.

There are no easy answers. But to people like Tilghman, the fact that academia now has to seriously grapple with these questions is welcome news.

There are no easy answers. But to people like Tilghman, the fact that academia now has to seriously grapple with these questions is welcome news.

“Nothing will be more beneficial to the academic life science enterprise than getting some real competition,” she said. “I see this as immensely healthy.”

About the Author

By Jonathan Wosen

West Coast Biotech & Life Sciences Reporter

Jonathan is STAT’s West Coast biotech & life sciences reporter.

Originally published at https://www.statnews.com on November 10, 2022.