Time for united action on depression: A Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission

The Lancet

Prof Helen Herrman, MD *; Prof Vikram Patel, PhD *; Christian Kieling, MD *; Prof Michael Berk, PhD †; Claudia Buchweitz, MA †; Prof Pim Cuijpers, PhD †; et al.

February 15, 2022

This is an excerpt of the publication above, focusing on “Section 3— The roots of depression”

Executive Summary:

by Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Chief Editor of “The Health Strategist” blog

Three key observations have shaped the understanding of why some people become depressed.

- First, depression tends to run in families, often jointly with bipolar disorder, substance use, and anxiety disorders.

- Second, onset of depression in adolescents and adults is in most cases preceded by childhood-onset disorders, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and anxiety disorders.

- Third, most early episodes of depression have an onset shortly after a stressful life event, especially one involving loss, disappointment, or humiliation, particularly in people primed by early loss, neglect, or trauma.

Although these three observations might suggest genetic, developmental, and environmental origins of depression, they also suggest that no single factor provides a complete explanation of why depression develops.

The unique interplay of these factors, operating at different points of the life course, constitute the roots of depression in any individual.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpted)

Three key observations have shaped our understanding of why some people become depressed.

- First, depression tends to run in families, often jointly with bipolar disorder, substance use, and anxiety disorders.

Children of parents with depression or bipolar disorder have an elevated risk of developing depression themselves even when they are not raised by their biological parents.

However, many children of affected parents do not manifest the syndrome, and most people with depression have unaffected parents.

- Second, onset of depression in adolescents and adults is in most cases preceded by childhood-onset disorders, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and anxiety disorders.

However, most children with ADHD or anxiety disorders will not develop depression as adults.

- Third, most early episodes of depression have an onset shortly after a stressful life event, especially one involving loss, disappointment, or humiliation, particularly in people primed by early loss, neglect, or trauma.

Nevertheless, all people encounter stressful life events and most do not develop depression in the aftermath.

Although these three observations might suggest genetic, developmental, and environmental origins of depression, they also suggest that no single factor provides a complete explanation of why depression develops.

The unique interplay of these factors, operating at different points of the life course, constitute the roots of depression in any individual.

Table of Contents (TOC)

- Predisposing and protective factors

- Precipitating and perpetuating factors

- Integrative models of pathogenic mechanisms

- The neural pathways of depression

Predisposing and protective factors

With systematic follow-up of large representative sample groups from childhood to adulthood, the onset of a major depressive episode is not typically the first manifestation of psychopathology.

In most cases, depression is preceded by childhood symptoms or disorders, including oppositional-defiant disorder, ADHD, and anxiety disorders. 256

The prospective association between anxiety and depression is particularly strong and well established. 257

The prospective association between ADHD and depression is more complex and might be particularly relevant for early-onset depression.

Depression that manifests in childhood or early adolescence might be related to genetic liability to ADHD and other neurodevelopmental disorders 258 as well as environmental risk factors.

Childhood ADHD and anxiety disorders also both predict bipolar disorder, which can start as adolescent-onset depression. 259

Among the offspring of parents with depression, the risk of developing depression by early adulthood is 40%, a more than two-fold increase compared with offspring of parents without mood disorders.

Analysis of an entire country’s population, including individuals raised by their biological families and individuals raised by adoptive families, suggests that familial risk for depression is due to approximately equal contributions of genetic and environmental factors that are shared within families. 261

The genetic risk of depression is probably due to small effects of hundreds or thousands of common genetic variants, with overrepresentation of genes affecting brain development, inflammation, bioenergetics, and neuronal signalling.

The large number of common variants involved entails that every individual carries some risk variants for depression, and a polygenic score (indexing the individual’s load of risk variants) predicts the genetic liability to depression better than any specific genetic variant.

Additionally, the predictive power of molecular genetic information falls far short of estimates from family and twin analyses, indicating that the contribution of genetic variants to depression also depends on the environmental context.

Much research has been done on early childhood adversities, suggesting that they are associated with an increased susceptibility to depression (as well as other psychopathology and somatic illnesses) in adulthood in the presence of stressful life events.

Substantial evidence supports the idea that experiencing maltreatment during critical periods early in life increases a person’s predisposition to a subsequent or later depressive episode.

Moreover, convincing evidence indicates that experiencing maltreatment in childhood increases the likelihood of exhibiting an unfavourable course of illness, with higher rates of recurrence and persistence in adulthood.

Personality traits (which themselves have a variety of genetic and environmental roots) are also associated with increased susceptibility to depression.

For example, the construct of neuroticism or negative affectivity has been shown to be associated with an increased probability of experiencing stressful life events and of subsequently responding to these events with depression.

Cognitive models propose that individuals at risk for depression exhibit biases in information processing, resulting in interpretations that are pessimistic and self-critical, leading to so-called depressogenic cognitive styles.

Variables related to an individual’s interpersonal style might also represent risk factors for developing depression, possibly due to their contribution to stressful conflict and loss events.

The modal clinical presentation of people with personality disorders is a complaint of depression and a large proportion of people with depression have a comorbid personality disorder.Such comorbidity has adverse prognostic and therapeutic implications.

Lifestyle habits have also been consistently associated with depression.

Meta-analytic evidence supports an association of low levels of physical activity and unhealthy dietary patterns with an increased risk of developing depression.

Previous use of substances has been shown to increase the predisposition to depression; for example, adolescent cannabis consumption has been associated with increased risk of developing the disorder in early adulthood.

A meta-analysis reported an association between tobacco smoking and increased risk of depression in cross-sectional studies, with the relationship maintained across several moderators.

However, the overall strength of associations is variable, and few data are available to indicate the direction of causality between most lifestyle factors and depression, with a strong probability of bidirectional causation in most cases.

The importance of social determinants suggests that a perspective beyond the individual level is also required to deal with factors influencing depression.

Population health science focuses on structural factors and on how they shape the health of individuals within and across populations.

Many of the Sustainable Development Goals, such as reducing gender and other inequities, and effective climate action, align closely with factors that affect the risk of depression.

There is now a large evidence base that intimate partner violence and sexual abuse, which are endemic globally, are major risk factors for depression, particularly in women, who are more likely to experience such violence, including coercive controlling behaviours.

Income inequality has been shown to be consistently positively associated with the risk of depression, with most of the available evidence from high-income countries.

The relationship between poverty and depression is complex and likely to be characterised by both social causation (ie, social and economic adversities increase the risk of depression) and social selection (ie, people with depression drift into poverty) mechanisms. The experience of forced displacement due to conflict, climate change, and other causes is associated with high prevalence of depression, with numerous studies identifying between a third and half of refugees and internally displaced populations meeting criteria for depression on self-report questionnaires.

Following the evidence regarding the effect of natural and built environments on physical health, emerging data suggest the relevance of biophysical factors such as air pollution, persistent organic and heavy metal pollutants, and ambient noise in increasing the risk for developing depression.

Conversely, some personal characteristics, interests, skills, and social support variables might constitute strengths that mitigate the effect of depression.

Protective factors increase a person’s resilience (ie, the ability to maintain or regain mental health in the face of adversity or to bounce back from hardship and trauma).

Factors such as history of secure attachment, cognitive abilities, self-regulation abilities, and positive peer or community support have been identified as contributing to resilience and enabling at-risk individuals to adapt or respond well to stressors. Resilience can be context-specific and time-specific, and might not be present across all life domains; individuals might be resilient to one environmental hazard but not to others, and might exhibit resilience at one period in their lifetime but not at other points.

From a systemic point of view, the capacity of the physical and social environments to facilitate the coping process of the individual in a culturally meaningful way is also of utmost importance.

An adequate clinical assessment should not only investigate mental phenomena potentially relevant to overcome negative circumstances, but also explore past situations in which the individual and his or her environment dealt with adversity, as previous successes might be relevant for current and future challenges.

Precipitating and perpetuating factors

Precipitating factors occur shortly before the onset of depression, possibly interacting with predisposing factors to trigger the disorder.

Many studies adopt the overarching term stressful life events to encompass experiences such as bereavement, separation, life-threatening situations, medical illnesses, being subjected to violence, peer-victimisation (eg, bullying), loss of employment, and separation or divorce.

There is substantial evidence corroborating the precipitating role of such proximal environmental influences in the development of depression.

However, a large proportion of individuals are apparently less vulnerable to these experiences.

Childhood sensitisation through trauma or neglect can play a role in influencing each person’s level of vulnerability or resilience.

Additionally, individuals with depression have an increased propensity to experience acute stressors compared with those without a history of depression. This perpetuating pattern of designated stress generation is particularly relevant for interpersonal events.

Other factors contributing to the recurrence and persistence of depression include substance use, behavioural patterns such as social withdrawal, and cognitive biases in attention, memory, and interpretation.

A ruminative response style (characterised by an over-analysis of problems) tends to intensify negative, self-focused thoughts, and to hamper problem-solving, perpetuating symptoms of depression.

Identifying maintaining factors for any one person might help achieve sustained recovery.

Integrative models of pathogenic mechanisms

Discrete risk or protective factors associated with the onset and continuity of depression account for only a small proportion of the complexity of this condition.

Multiple factors are likely to operate through a probabilistic chain that is conditioned by timing, dosage, and context, in which upstream distal factors (indirectly or distantly and less specifically related to onset) influence more downstream proximal factors (affecting the individual closer to the onset of the condition and often more directly).

The understanding is further complicated by the evidence that no risk factor appears to be either necessary or sufficient, that the same risk factor might confer increased risk for various mental disorders, and that many individuals exposed to risk factors do not develop depression.

Although theories emphasising one aspect of causation have been applied with a modest degree of success (eg, monoamine hypothesis, cognitive theory, interpersonal theory), a broadly applicable model of depression will need to incorporate genetic, developmental, and environmental factors and allow for heterogeneity of causation across individuals.

Most conceptualisations that fulfil these requirements are variants of the so-called diathesis-stress model (alternatively referred to as vulnerability-stress model). The diathesis-stress model posits that, following an acute stressor, a person who carries a diathesis (or vulnerability) that renders them sensitive to the stressor will develop depression.

The vulnerability could have both biological (eg, genetic, endocrine, inflammation, or brain connectivity) and psychological (eg, temperament, personality, or beliefs) features.

Each person can carry a number of vulnerabilities that might add on to an overall diathesis or might result in sensitivity to different types of stressors.

There is probably a complementary relationship between the degree of vulnerability and the severity of the stressor: a person with a high degree of vulnerability might develop depression even with a mild stressor, and a person with a low degree of vulnerability might only become depressed if encountering a stressor of extraordinary severity.

With the accrual of studies on the joint effects of genetic and environmental factors in the causation of depression, the general diathesis-stress model can now be considered proven beyond reasonable doubt.

More developmentally informed models, referred to as transactional models, also account for the fact that vulnerability can change over time due to biological events (eg, menarche or childbirth) and changes in the external environment.

For example, exposure to adverse environments earlier in life or even in utero might not be sufficient to cause depression, but could create a vulnerability that will render the individual more likely to develop depression following a further stressful experience.

Furthermore, the same characteristic might make an individual sensitive to negative effects of adverse experiences and beneficial effects of positive experiences. This more inclusive conceptualisation of personal vulnerability and potential has been described as the differential susceptibility model.

The diathesis-stress and differential susceptibility models raise questions about the nature of individual vulnerability.

To distinguish cause and effect, consider-ation of individually stable and changeable aspects of vulnerability separately is useful.

Genetic variation provides an unbiased source of information about vulnerability because genetic sequence is believed to remain unchanged from conception and throughout the life of an individual.

Therefore, specifications of the diathesis-stress model that involve genetic measurement facilitate the study of causality. These genetic models include gene-environment correlation and gene-environment interaction.

Gene–environment correlation occurs when a genetic variant makes an individual more likely to be exposed to a particular aspect of the environment.

Some recently identified gene-environment correlations challenge the assumption that genes and environment are separate primary causal factors.

Individuals with a high loading of depression-related genetic variants report more stressful life events, even life events that are typically thought to be relatively independent of the individual.

For example, polygenic scores for depression, lower intelligence, and greater body weight predict whether an individual will be bullied.

These findings stimulate a reconceptualisation of the diathesis-stress model to incorporate the interdependence of stressor and vulnerability.

Gene-environment interaction occurs when a genetic variant makes an individual more sensitive to the effect of an environmental exposure. Incorporation of gene-environment interactions improves the prediction of depression compared with the polygenic risk score approach.

Stressful life events are more likely to lead to depression in individuals who have a higher load of genetic risk variants.

Genetic factors that render individuals more sensitive to both negative and positive environmental exposures can be measured, in the form of a polygenic score. This polygenic sensitivity score predicts greater negative and positive responses to adverse and beneficial exposures, supporting the differential-susceptibility model.

Some of the most powerful environmental factors are far removed in time from the actual onset of depression.

For example, childhood maltreatment and bullying are associated with increased vulnerability to depression lasting for the individual’s lifetime, raising the question of how non-genetic vulnerability factors remain active over long time periods.

Psychological and personality development theories might account for this observation.

Equally, epigenetic modifications provide a suitable mechanism for such long-term memory.

Exposure to adverse environments early in life could lead to modifications of the genome, such as DNA methylation, which will continue to affect the expression of genes for prolonged periods of time without altering the genetic sequence. ]

Although specific epigenetic modifications have been associated with experimental exposures in animal models, finding a reproducible epigenetic signature of adversity in humans has been challenging.

Exposure to adversity in childhood has also been found to increase the amount of systemic inflammation. 306

The long-term increase of inflammatory activity might play a role in the pathogenesis of depression, as symptoms of depression overlap with those of inflammatory disease.

The present models of depression are being challenged by factors that do not easily fit into the gene-environment dichotomy.

One such factor is the gut microbiome, the ensemble of bacteria living in the human digestive tract, which is individually variable and is affected by human genetic makeup, diet, and other aspects of the environment.

The fact that the microbiome is itself genetic in nature opens a host of possibilities, including complex interactions between human and bacterial genomes.

Gut bacteria can produce neuroactive substances, including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and serotonin, which can affect the brain of the human host. 307

Animal models have shown that a depressive phenotype can be transferred to a non-depressed animal by microbiome transplants from a depressed donor, and that depressed animals can have the phenotype removed by transplant from a non-depressed donor. 308

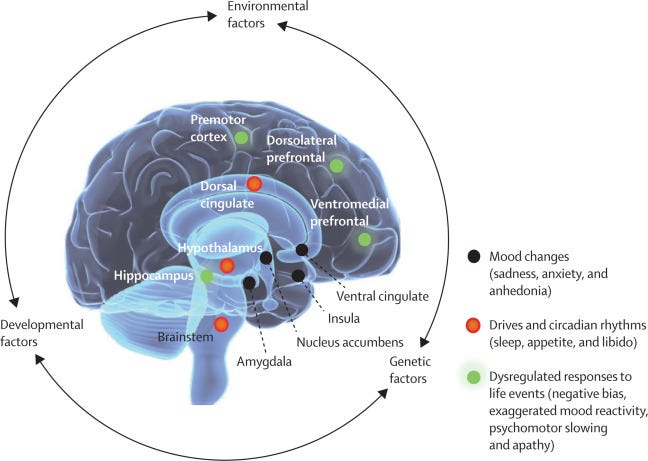

The neural pathways of depression

The hundreds of genetic variants associated with depression, each of very low effect, are most concentrated among genes that are expressed in the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate. 263

These same brain areas show accelerated breakdown of monoamine neurotransmitters, 309 increased neuroinflammation, 310 reduced grey matter, 311 and heightened reactivity to mood-relevant stimuli 312 in individuals with depression.

This convergence of evidence leaves little doubt that, despite the importance of genetics and the environment, the final pathways of depression pathology occur in multiple but mutually interactive areas of the human brain (figure 5).

Figure 5 Neural underpinnings of depression

Over the past 30 years, brain imaging has leveraged a conceptual shift in depression research.

The dominant psychological and neurochemical theories of the past have been reframed to accommodate complemen-tary genetic, developmental, molecular, and brain circuit models.

The early findings that have been replicated most consistently — frontal hypometabolism and hippocampal atrophy 313 , 314 — remain foundational to current models of depression, although they are not pathognomonic.

A conspicuous contradiction is that many individuals do not show these core changes, or demonstrate opposite patterns (eg, frontal hypermetabolism).

Increasing recognition of these individual differences, probably masked by the focus of earlier studies on group effects, assists the understanding of clinical heterogeneity in depression. 315 , 316

Other limbic (amygdala, insula, and cingulate) and subcortical (basal ganglia, thalamus, periaqueductal grey, dorsal raphe, and lateral habenula) abnormalities have also been reported, especially with the introduction of resting and task-based functional MRI and functional connectivity analyses.

These findings are similarly variable. Differences among subgroups of people with depression, as well as variations in the degree of illness severity and duration, and the heterogeneous expression of clinical symptoms among those tested might contribute to the observed variance, 317 , 318 although there is so far no consensus on the explanation for these results.

The investigation of neural mechanisms sub-serving depression pathogenesis and progression continues based on the assumption that this is unlikely to be a disease of a single gene, brain region, or neurotrans-mitter system.

Depression is now modelled as a neural systems disorder. A depressive episode is viewed as the net effect of ineffective network regulation in the context of emotional, cognitive, or somatic stress. 315 , 319

Employing this contemporary interconnected view, studies extend beyond properties of individual brain regions to examine integrated pathways and distributed neural networks.

Technological and analytical advances, 319 , 320 , 321 , 322 including routine use of big data, make it possible to acquire multiple neuroimaging data in the same individual in a single session.

Additionally, public availability of large multimodal imaging datasets is increasing.

Translational studies using cell-specific animal models of depression-relevant behaviours further inform the interpretation of multimodal imaging data in people at all stages of risk and illness. 324 , 325 , 326

Such studies have revealed subtle abnormalities of individual regions and pathway structure and function.

Definitive precipitants or mediators of such so-called systems dysfunction are not yet characterised.

However, several factors (including those described earlier in this Section) appear to be strong contributors.

In addition to acute and chronic life stressors, these factors include genetic vulnerability, affective temperament, developmental insults, and early childhood trauma. 327 , 328 , 329

Depression network models have also evaluated mediators and moderators of resilience. Such studies draw upon animal models of acute and chronic stress exposure. 330 , 331

Converging findings across species point to the crucial role of cortico-limbic circuitry in the experience of depression, with different regional abnormalities emerging at different ages and developmental stages.

A prominent observation is the involvement of distinct prefrontal cortical subregions and their connections to numerous subcortical structures, including the cingulate, hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens, dorsal raphe, and other brain stem nuclei. 324 , 325 , 326

Links of these cortico-limbic circuits to physiological functions common to both chronic stress exposure and depression have emerged, including disruption of circadian functions, affective states, drives, motivation, intention, and action.

All these disturbances logically contribute to symptoms of low energy; apathy; anhedonia; negative mood; and changes in appetite, sleep, and libido.

These circuit aberrations can also result in anxiety, rumination, negative cognition, and maladaptive habits.

In the animal stress models, structural alterations (ie, atrophy and morphological changes in neurons and glia) and functional adaptations (ie, changes in blood flow, metabolism, and gene expression) are observed, paralleling abnormalities seen in imaging and post-mortem studies of people with major depression.

Chronic stress has additional time-dependent influences on systemic physiology. Immune, neuroendocrine, autonomic, metabolic, and molecular mediators have further influence on cortico-limbic function in a bidirectional manner.

This cascade of reactions probably affects cellular structure and function, neural network dynamics, and peripheral organ function, with differential effects in resilient and susceptible individuals.

Understanding brain plasticity and adaptive mechanisms, including their time course and trajectory, can be crucial to the effective timing and delivery of various interventions.

These observations might have important implications for treatment and prognosis; for example, different treatments appear to modulate distinct network nodes and their local and distant connections, and response might depend on targeting specific biological abnormalities. 332

Furthermore, the cascade of chemical and molecular adaptations that occur with depression and stress exposure might have a range of consequences, including irreversible structural and molecular damage that could underlie treatment resistance. 324

Nowadays, imaging studies are designed to explicitly develop biomarkers of treatment-specific subtypes that can guide optimal treatment selection for each person and signify treatment classes that should be avoided because they are unlikely to be helpful. 333 , 334

Furthermore, treatments are now being tested to target chemical as well as imaging biotypes. 335 , 336 , 337 , 338

Continues on Section 4

Originally published at https://www.thelancet.com.