This is a republication of the article below, with the title above.

An End to Error

Fifteen years after a “moral moment” (2001–2016) transformed patient safety here, new systems and a change in culture have gone a long way toward eradicating errors.

Hopkins Medicine

BY KAREN NITKIN AND LISA BROADHEAD

Illustrations by Andre de Loba

Spring/Summer 2016

Linell Smith and Patrick Smith also contributed to the reporting of this article.

Site Editor

Joaquim Cardos MSc.

health transformation – journal

September 18, 2022

On March 4, 2001, George Dover stood outside a Baltimore County home, rang the doorbell and changed the future of Johns Hopkins Medicine.

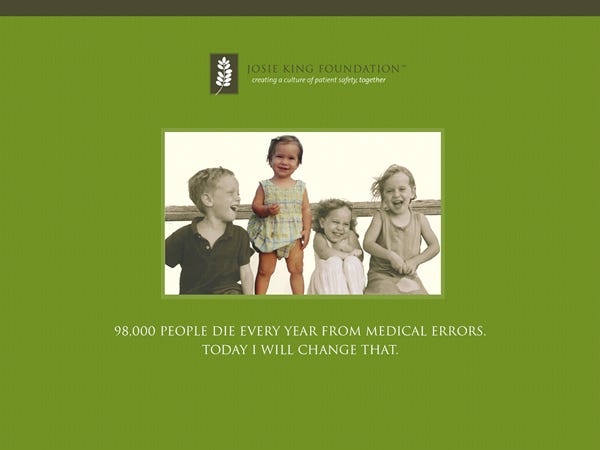

The director of the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center had come to the home of Tony and Sorrel King to apologize to the grieving parents.

Six weeks earlier, the Kings’ 18-month-old daughter, Josie, had wandered into an upstairs bathroom, turned on the hot water and climbed into the tub.

By the time her screams brought her mother, Josie had second-degree burns on more than half of her body.

The toddler was rushed to The Johns Hopkins Hospital, where she received skin grafts and healed.

Within weeks, she was acting like her old self.

But then she developed a central line-associated bloodstream infection-an infection today known to be preventable.

The infection ultimately led to septic shock, and Josie King died on Feb. 22.

The day Josie died, her Johns Hopkins-affiliated pediatrician, Lauren Bogue, walked into Dover’s office.

She encouraged him to visit the King family and accept responsibility on behalf of Johns Hopkins.

The unusual proposal quickly won full support from Johns Hopkins leadership-even its lawyers. Bogue arranged the meeting and accompanied Dover.

The pain inside the house was palpable, she recalls.

“The first thing I said to the Kings was that I was terribly sorry,” says Dover. “In those days, that was not fashionable.

We told Tony and Sorrel we would find out exactly what had happened, we would communicate what we found and we would do our best to make sure it never happened again.”

Dover kept his word, telephoning Sorrel every Friday morning, even when there was little to report.

On June 2, 2001, a second tragedy occurred.

Ellen Roche, a healthy 24-year-old technician at Johns Hopkins’ Asthma and Allergy Center, died of lung failure less than a month after inhaling an irritant medication while participating in an asthma research study.

Ten days after Roche’s death, the U.S. Office for Human Research Protections suspended all federally funded human subject research at Johns Hopkins, halting nearly 2,500 investigations for several months.

The two deaths shattered Johns Hopkins, propelling what some consider the most significant culture change in its history.

The two deaths shattered Johns Hopkins, propelling what some consider the most significant culture change in its history.

“These events created a moral moment where we had to make a choice,” says Peter Pronovost, director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality.

“It was: Are we going to openly address our shortcomings? Or are we going to hide behind our brand and say all is well? Leadership stood up and said, ‘We need to start talking about this.’”

Leadership stood up and said, ‘We need to start talking about this.

In the 15 years since that fateful crossroads, as the health care system expands, Johns Hopkins Medicine has pioneered a culture of accountability and patient safety advances.

By 2015, all six Johns Hopkins hospitals were recognized by the Joint Commission in its Top Performer on Key Quality Measures program.

Johns Hopkins programs and safety metrics have been adopted around the world.

By 2015, all six Johns Hopkins hospitals were recognized by the Joint Commission in its Top Performer on Key Quality Measures program.

Johns Hopkins programs and safety metrics have been adopted around the world.

But before that could happen, safety had to become the top priority.

Research oversight became more stringent; two Institutional Review Boards became seven.

Today, “we have a whole process to identify a high-risk protocol like the one Ellen Roche was in,” says Dan Ford, vice dean for clinical investigation-a position created after Roche’s death.

“We conduct research in the safest possible setting. Each research team has to know how it would handle an emergency.”

Today, “we have a whole process to identify a high-risk protocol like the one Ellen Roche was in,” … …says Dan Ford, vice dean for clinical investigation-a position created after Roche’s death.

On the clinical side, opportunities for error continue to be systemically eradicated by changing procedures, equipment, even the culture within units.

The Armstrong Institute, founded in 2011, leads this effort while training a new generation of patient safety innovators.

On the clinical side, opportunities for error continue to be systemically eradicated by changing procedures, equipment, even the culture within units.

The Armstrong Institute, founded in 2011, leads this effort while training a new generation of patient safety innovators.

A Top Priority

The deaths of King and Roche made patient safety personal-and urgent.

“We took the position that the buck had to stop at the top of the organization,” says Ronald R. Peterson, president of The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Health System and executive vice president of Johns Hopkins Medicine.

“It was our responsibility to take definitive steps to address this.”

“We took the position that the buck had to stop at the top of the organization,”

The effort began with three bold steps:

- Make safety the №1 priority of Johns Hopkins Medicine.

- Start every board of trustees meeting with a safety report instead of a financial review.

- And create a safety-focused Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care, funded with $500,000 each from The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and The Johns Hopkins University.

“Improving patient safety wasn’t a choice at Johns Hopkins,” says Lori Paine, who filled the newly created role of patient safety coordinator and is now director of patient safety for The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Armstrong Institute. “It was an obligation.”

When Tony and Sorrel King received a settlement from Johns Hopkins, they created the Josie King Foundation and donated money to Johns Hopkins for patient safety programs.

“She held us accountable,” Pronovost says of Sorrel. “She didn’t want what happened to Josie to happen to anybody else.”

“She held us accountable,” Pronovost says of Sorrel. “She didn’t want what happened to Josie to happen to anybody else.”

Safety as Science

Nearly 200 separate tasks are required to reduce preventable harm for a single intensive care patient, notes the Armstrong Institute. Johns Hopkins began treating safety like a science, collecting data to find, test and deploy systemic improvements.

An early target for this approach: health care-associated bloodstream infections that are acquired through central-line catheters and are often preventable.

In 2001, the same year that more than 43,000 of these infections occurred in intensive care units (ICUs) across the United States, Pronovost and his infection control colleagues distilled 120 pages of information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention into a five-step checklist that was distributed to intensive care units.

In 2001, the same year that more than 43,000 of these infections occurred in intensive care units (ICUs) across the United States

Movable carts were created with all the tubes, drapes and other equipment necessary for insertions. Doctors would no longer have to search for items in eight separate locations.

But the key step was empowering nurses to act if they saw doctors skipping items on the checklist. “People need to know that if someone they see above them is doing something that is dangerous to the patient, they have every right to speak up,” says Edward Miller, former CEO of Johns Hopkins Medicine and dean of the school of medicine.

It was a major culture shift, embraced by top leadership but resisted by some physicians.

It was a major culture shift, embraced by top leadership but resisted by some physicians. …“Some of the senior doctors said, ‘I’ll be darned if some nurse is going to tell me what to do,’”

“Some of the senior doctors said, ‘I’ll be darned if some nurse is going to tell me what to do,’” recalls William Brody, former president of The Johns Hopkins University.

“One time I got a complaint from a doctor, and I said to the nurse, ‘Just put my name and phone number up on the nursing station. Call me, even if its 2 in the morning, and I’ll come in and have a conversation.’ I never had to.”

Compliance skyrocketed.

Pronovost and his colleagues estimated that the checklist prevented 43 infections and eight ICU deaths over two years, and saved the hospital $2 million in health care costs.

Before long, checklists became a standard, lifesaving component of health care nationwide.

Pronovost and his colleagues estimated that the checklist prevented 43 infections and eight ICU deaths over two years, and saved the hospital $2 million in health care costs.

The new culture of accountability led to the creation of the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP), developed at Johns Hopkins more than 10 years ago.

CUSP gives all caregivers tools and support to address problems such as hospital-acquired infections, medication administration errors or communication breakdowns.

The new culture of accountability led to the creation of the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP), developed at Johns Hopkins more than 10 years ago.

More than 170 CUSP teams have been activated at Johns Hopkins Medicine, and hundreds more have been organized in hospitals internationally.

The results are striking.

With CUSP teams and checklists in 1,100 ICUs in 44 U.S. states,

- bloodstream infections dropped by 40 percent in those hospitals,

- saving more than 500 lives,

- preventing more than 2,000 bloodstream infections and

- averting $34 million in health care costs, according to results announced in 2012.

In another strategy to improve the safety of systems, The Johns Hopkins Hospital hired Peter Doyle in 2007 as its first human factors engineer.

A goal of his profession, Doyle explains, is to optimize patient safety by studying how clinicians interact with medical devices in complex, interconnected and often hectic work environments.

This includes working with nurses and clinical engineers to reduce unnecessary patient monitoring alarms, assisting in the selection of the safest pumps for infusing medications, and assuring that laboratory specimens are properly labeled for diagnostic accuracy.

The Armstrong Institute

Medical mistakes nearly killed C. Michael Armstrong.

First, doctors at another hospital missed signs that he had leukemia. Then, he developed a serious infection post-chemotherapy.

After a tough battle in the ICU, he lived.

Years later, he was belatedly diagnosed with advanced cancer and given a 50–50 chance of living five years.

If he survived, he vowed, he would “do something big” for patient safety.

Armstrong finished treatment in 2009. Two years later, he donated $10 million to Johns Hopkins to create the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality.

Armstrong finished treatment in 2009. Two years later, he donated $10 million to Johns Hopkins to create the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality.

The institute, headed by Pronovost, combines safety specialists from across Johns Hopkins, bringing “common purpose, programs, education, training, objective measurements and, probably more important than anything, accountability,” says Armstrong.

For example, he says, prescription errors have been dramatically reduced by automating the multistep process with bar codes, scanners and confirmation checks.

For example, he says, prescription errors have been dramatically reduced by automating the multistep process with bar codes, scanners and confirmation checks.

The institute’s Patient Safety and Quality Leadership Academy, a nine-month multidisciplinary training program for future quality and safety leaders, has trained 60 employees so far, says Melinda Sawyer, assistant director of patient safety for the institute.

Of those, she says, 94 percent now lead quality and safety projects at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

They are working to improve patient experiences, prevent harm during handoffs, minimize health care disparities between populations and decrease the number of missed diagnoses.

Four years after her daughter’s death, Sorrel King asked Pronovost a question that haunts him to this day: “Would Josie be less likely to die now?”

Pronovost and others at Johns Hopkins continue working to ensure that the answer is yes.

Four years after her daughter’s death, Sorrel King asked Pronovost a question that haunts him to this day: “Would Josie be less likely to die now?”

Pronovost and others at Johns Hopkins continue working to ensure that the answer is yes.

Originally published at https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org.

Zero Errors

“When we started, our bloodstream infection rates were twice the national average. Some of our doctors said the goal should be to get to the national average. I said, if we want to be the best hospital, we have to be the very best. Patients expect zero errors. On that basis, Peter Pronovost developed the whole system, including the checklist, which led to reducing central -line infections to basically zero.”

William Brody

President, The Johns Hopkins University, 1996–2009

JOSIE KING’S LEGACY

“I have a clear memory of hearing Josie’s story at my new-hire orientation six years ago. It set the tone as to the type of organization Johns Hopkins is. I worked for two other organizations prior, and such a transparent discussion around errors was never an emphasis, especially at a new-hire orientation. It was clear that a culture of safety was important to this organization.”

Nichole Jantzi

Patient Safety Program Administrator, Johns Hopkins Community Physicians

Names mentioned:

Peter Pronovost, director of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality.

Dan Ford, vice dean for clinical investigation-a position created after Roche’s death.

Ronald R. Peterson, president of The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Health System and executive vice president of Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Lori Paine, who filled the newly created role of patient safety coordinator and is now director of patient safety for The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Armstrong Institute

Edward Miller, former CEO of Johns Hopkins Medicine and dean of the school of medicine.

William Brody, former president of The Johns Hopkins University.

Peter Doyle in 2007 as its first human factors engineer.

Video