What is the message?

The launch of Nightingale Open Science, spearheaded by Ziad Obermeyer, represents a groundbreaking initiative to leverage curated medical datasets in training artificial intelligence (AI) to predict medical conditions earlier and improve patient outcomes.

By shifting from collecting “big data” to focusing on meaningful, curated data, this endeavor aims to address existing biases in healthcare algorithms and enhance the accuracy and inclusivity of AI-driven healthcare solutions.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

What are the key points?

Unique Health Data Sets: Nightingale Open Science offers a repository of curated medical datasets, funded by Eric Schmidt, encompassing 40 terabytes of medical imagery and patient outcomes. These datasets enable AI algorithms to predict medical conditions earlier and optimize patient care.

Addressing Bias in Healthcare Algorithms: Previous healthcare algorithms have exhibited biases, favoring healthier white patients over sicker black patients due to reliance on flawed proxies such as healthcare costs. Nightingale’s datasets, labeled with ground truth outcomes, aim to rectify these biases and improve healthcare equity.

Expanding Diversity and Accuracy: Unlike previous datasets, Nightingale’s datasets prioritize diversity and accuracy, reflecting the real-world population and improving algorithmic applicability and accuracy.

Global Impact: Nightingale’s initiative extends beyond the US and Taiwan, with plans to expand to Kenya and Lebanon, aiming to capture diverse medical scenarios and enhance global healthcare outcomes.

Future Prospects: The initiative signals a paradigm shift in AI research, emphasizing the critical role of high-quality, diverse datasets in advancing healthcare AI applications and mitigating biases.

What are the key examples?

Obermeyer’s research revealed biases in healthcare algorithms, highlighting the importance of utilizing curated datasets with ground truth outcomes to address disparities in patient care.

Nightingale’s datasets, unlike previous datasets, prioritize diversity and accuracy, contributing to the development of more inclusive and accurate AI-driven healthcare solutions.

What are the key statistics?

Nightingale’s datasets encompass 40 terabytes of medical imagery and patient outcomes, offering a comprehensive resource for training AI algorithms.

Nearly 47% of black patients were under-referred for extra care due to biases in healthcare algorithms relying on flawed proxies like healthcare costs.

Conclusion

Nightingale Open Science’s initiative marks a pivotal step towards harnessing AI to revolutionize healthcare by leveraging curated datasets to predict medical conditions earlier and mitigate biases in healthcare algorithms.

By prioritizing diversity, accuracy, and inclusivity, this endeavor holds the potential to transform patient care globally and drive innovation in AI-driven healthcare solutions.

DEEP DIVE

Trove of unique health data sets could help AI predict medical conditions earlier

Financial Times

January 3, 2022

Ziad Obermeyer, a physician and machine learning scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, launched Nightingale Open Science last month — a treasure trove of unique medical data sets, each curated around an unsolved medical mystery that artificial intelligence could help to solve.

The data sets, released after the project received $2m of funding from former Google chief executive Eric Schmidt, could help to train computer algorithms to predict medical conditions earlier, triage better and save lives.

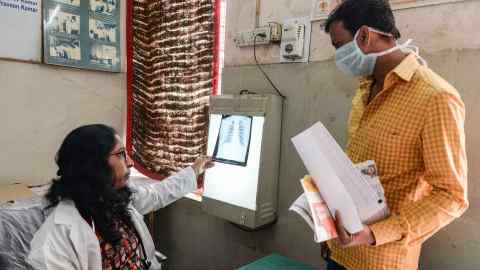

The data include 40 terabytes of medical imagery, such as X-rays, electrocardiogram waveforms and pathology specimens, from patients with a range of conditions, including high-risk breast cancer, sudden cardiac arrest, fractures and Covid-19.

Each image is labelled with the patient’s medical outcomes, such as the stage of breast cancer and whether it resulted in death, or whether a Covid patient needed a ventilator.

Obermeyer has made the data sets free to use and mainly worked with hospitals in the US and Taiwan to build them over two years.

He plans to expand this to Kenya and Lebanon in the coming months to reflect as much medical diversity as possible.

“Nothing exists like it,” said Obermeyer, who announced the new project in December alongside colleagues at NeurIPS, the global academic conference for artificial intelligence.

“What sets this apart from anything available online is the data sets are labelled with the ‘ground truth’, which means with what really happened to a patient and not just a doctor’s opinion.”

This means that data sets on cardiac arrest ECGs, for example, have not been labelled depending on whether a cardiologist detected something suspicious, but with whether that patient eventually had a heart attack.

“We can learn from actual patient outcomes, rather than replicate flawed human judgment,” Obermeyer said.

In the past year, the AI community has undergone a sector-wide shift from collecting “big data” — as much data as possible — to meaningful data, or information that is more curated and relevant to a specific problem, which can be used to address issues such as ingrained human biases in healthcare, image recognition or natural language processing.

In the past year, the AI community has undergone a sector-wide shift from collecting “big data” — as much data as possible — to meaningful data

Until now, many healthcare algorithms have been proven to amplify existing health disparities.

For instance, Obermeyer found that an AI system used by hospitals treating up to 70m Americans, which allocated extra medical support for patients with chronic illnesses, was prioritising healthier white patients over sicker black patients who needed help.

It was assigning risk scores based on data that included an individual’s total healthcare costs in a year. The model was using healthcare costs as a proxy for healthcare needs.

The crux of this problem, which was reflected in the model’s underlying data, is that not everyone generates healthcare costs in the same way.

Minorities and other underserved populations may lack access to and resources for healthcare, be less able to get time off work for doctors’ visits, or experience discrimination within the system by receiving fewer treatments or tests, which can lead to them being classed as less costly in data sets.

This doesn’t necessarily mean they have been less sick.

The researchers calculated that nearly 47 per cent of black patients should have been referred for extra care, but the algorithmic bias meant that only 17 per cent were.

“Your costs are going to be lower even though your needs are the same. And that was the root of the bias that we found,” Obermeyer said.

He found that several other similar AI systems also used cost as a proxy, a decision that he estimates is affecting the lives of about 200m patients.

Unlike widely-used data sets in computer vision such as ImageNet, which were designed using photos from the internet that do not necessarily reflect the diversity of the real world, a spate of new data sets include information that is more representative of the population, which results not just in wider applicability and greater accuracy of the algorithms, but also in expanding our scientific knowledge.

These new diverse and high-quality data sets could be used to root out underlying biases “that are discriminatory in terms of people who are underserved and not represented” in healthcare systems, such as women and minorities, said Schmidt, whose foundation has funded the Nightingale Open Science project.

“You can use AI to understand what’s really going on with the human, rather than what a doctor thinks.”

The Nightingale data sets were among dozens proposed this year at NeurIPS.

Other projects included a speech data set of Mandarin and eight subdialects recorded by 27,000 speakers in 34 cities in China; the largest audio data set of Covid respiratory sounds, such as breathing, coughing and voice recordings, from more than 36,000 participants to help screen for the disease; and a data set of satellite images covering the entire country of South Africa from 2006 to 2017, divided and labelled by neighbourhood, to study the social effects of spatial apartheid.

Elaine Nsoesie, a computational epidemiologist at the Boston University School of Public Health, said new types of data could also help with studying the spread of diseases in diverse locations, as people from different cultures react differently to illnesses.

She said her grandmother in Cameroon, for example, might think differently than Americans do about health.

“If someone had an influenza-like illness in Cameroon, they may be looking for traditional, herbal treatments or home remedies, compared to drugs or different home remedies in the US.”

Computer scientists Serena Yeung and Joaquin Vanschoren, who proposed that research to build new data sets should be exchanged at NeurIPS, pointed out that the vast majority of the AI community still cannot find good data sets to evaluate their algorithms.

… the vast majority of the AI community still cannot find good data sets to evaluate their algorithms.

This meant that AI researchers were still turning to data that were potentially “plagued with bias”, they said. “There are no good models without good data.”

Names mentioned

Ziad Obermeyer, a physician and machine learning scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, launched Nightingale Open Science last month

Nightingale Open Science

Former Google Chief Executive Eric Schmidt

Elaine Nsoesie, a computational epidemiologist at the Boston University School of Public Health

Computer Scientists Serena Yeung and Joaquin Vanschoren,