Linkedin

Bertalan Meskó, MD, PhD

May 27, 2022

“Did you know that at least one-third of women have lower back pain before their periods every month, and yet, nobody seems to fully understand why?” — asked a Medical Futurist team member a little while ago. The question led to a discussion about the differences in research, funding and understanding of male-only and female-only health issues, and consequently, to this article.

It is a well-known fact that some diseases or conditions dominantly affect one gender or the other. There are the trivial ones, like prostate cancer or ovarian, cervical, uterine cancers. But there is a long list of diseases and conditions that have a significantly higher prevalence among one of the sexes, like liver cancer or tuberculosis occurring more often in the male population, and autoimmune diseases or multiple sclerosis among the females.

Why does a symptom affecting 19% of men get five times more funding than a symptom affecting 90% of women?

The interesting thing is, that figures suggest that although roughly half the population is female pretty much all across the globe, research on female-dominant diseases is underfunded, while male-dominant ones are overfunded.

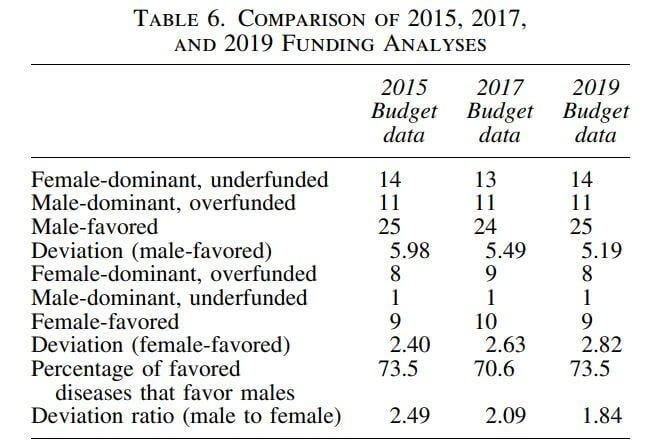

This is not something that is easily quantified, but this study tried to do this job. It came to the conclusion that “the degree of funding disparity for the male-favored diseases (extent to which male-dominant diseases are overfunded and female-dominant diseases underfunded) is nearly twice as large as that for the female-favored diseases.”

One easy to grasp example: premenstrual syndromes, affecting 90% of women, get one-fifth of the funding of erectile dysfunctions, affecting 19% of men. But the list goes on and on. Endometriosis, Alzheimer’s, Crohn disease, rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune conditions are just a few of the diseases that are affecting women significantly more and receive only a moderate amount of research funding.

Females were not included in clinical trials before 1993, not even in mice

Some of the reasons for the “gender gap” we see in health-research and its funding are historical. And we don’t even need to go back centuries, only a few decades to find some interesting things.

The US Food And Drug Administration (FDA) excluded women “of child-bearing potential” from all clinical trials between 1977 and 1993. This means that all these years all clinical trials were carried out exclusively on men. And not only in humans, but also in mice.

The reasons were two folds. Regulators were worried about potential complications of foetal malformation, following the European withdrawal of the sedative Thalidomide. This drug was used to suppress early pregnancy symptoms, and, as later was acknowledged, caused a vast number of birth deformities in the late 50’s. But this was not the only reason. Apparently, female hormonal cycles made things too complicated. The variability would mean more subjects were needed in clinical trials, thereby increasing costs. So including only male subjects in clinical trials was an economically justifiable solution. Or so it seemed.

No wonder, women have 50–75% more side effects from drugs

The fact that women generally experience significantly more side effects from various drugs is not surprising after knowing how they were not included in clinical trials for quite a long time. But 1993 was a while ago, things surely must have changed since then — we might think.

Apparently, things indeed have changed, but not so much. Some 80% of all drugs removed from the US market between 1997 and 2000 were withdrawn because their side effects occurred mainly or exclusively in women. And the trend continued. Between 2004 and 2013, women suffered more than 2 million drug-related adverse events, compared with 1.3 million for men in the United States.

Even in 2015, only about a third of participants in clinical trials for new treatments for cardiovascular disease were female, despite cardiovascular diseases being the number one cause of death in American women.

How about spending only a little more to have a ROI of 174,000 percent?

As this article explains, underfunding research about female health problems leaves a huge amount of money on the table. Sounds strange, right? After all, what we say is exactly that there should be more spending. But under-researched female health problems have incredible societal costs. Not only in the labour market, where conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune diseases and similar ‘womanly’ problems take off years of the careers of millions. But also in other areas: paying for the extra years in elderly care or losing the capacities of females, who are the primary caretakers in most families.

Researchers can provide shocking numbers to back their claims about why societies should focus more on female health.

For example, they examined what might happen if the budget for Alzheimer’s research into women specifically went from $288 million to $576 million. In these simulations, they conservatively assumed that this budgetary increase would deliver just 0.01 percent of health improvements for Alzheimer’s and coronary artery disease, and 0.1 percent for rheumatoid arthritis, over 30 years.

“Even these slivers of improvement produced a shockingly high return on investment. By doubling the NIH budget for research on coronary artery disease in women from its current $20 million, we could expect an ROI of 9,500 percent.

Studies focused on rheumatoid arthritis in women receive just $6 million a year. Doubling that would deliver an ROI of 174,000 percent and add $10.5 billion to our economy over the 30-year timespan” — the study says. Well, that is one hell of a ROI for sure.

So why don’t we spend on it if that is such a big business?

There is a huge amount of literature and debate about why exactly (and if at all) research targeting female health problems is underfunded in general. Some argue that the reason is quite simple: there are just too few female-targeted research initiatives, and instead of looking for discrimination, there should be more research projects submitted for funding.

Others see the situation a little more nuanced and believe that it is the result of many, overlapping structural problems, like the underrepresentation of women in science in general and especially in leading positions, the hard-to-pin but existing difference in the prestige of male and female researchers, gender inequities among decision-makers allocating funds and so on.

With all that said, these problems will surely not disappear by tomorrow, but we can expect that the development of healthcare and digital health tools will be part of the solution. Female health-related startups are definitely getting momentum — and funding — over the past decade, and the sheer amount of available health data coming from both genders will also contribute to a better understanding of the biological differences between how men and women react to drugs, treatments and ageing.

Originally published at https://www.linkedin.com.

Director of The Medical Futurist Institute (Keynote Speaker, Author & Futurist)