This is an excerpt of the publication “Understanding the High Prices That Commercial Health Insurers Pay Providers”, with the title above.

This is the Chapter 1 of the report “Policy Approaches to Reduce What Commercial Insurers Pay for Hospitals’ and Physicians’ Services”, published by CBO (Congressional Budget Office), in September 2022.

Site Editor:

Joaquim Cardoso MSc.

The Health Strategist — Management Journal

September 30, 2022

Infographic:

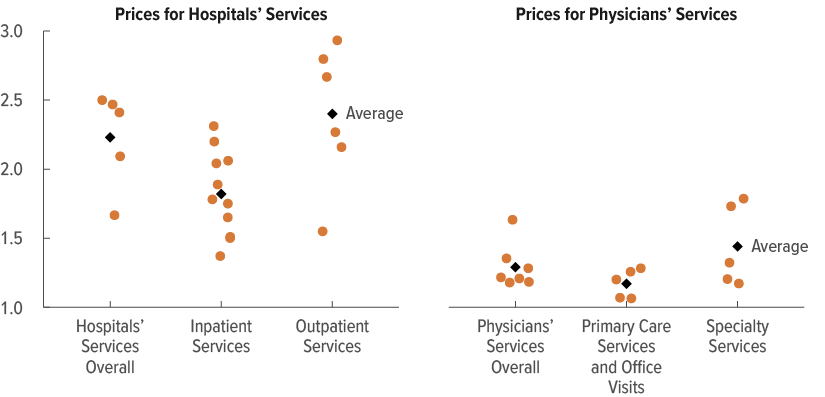

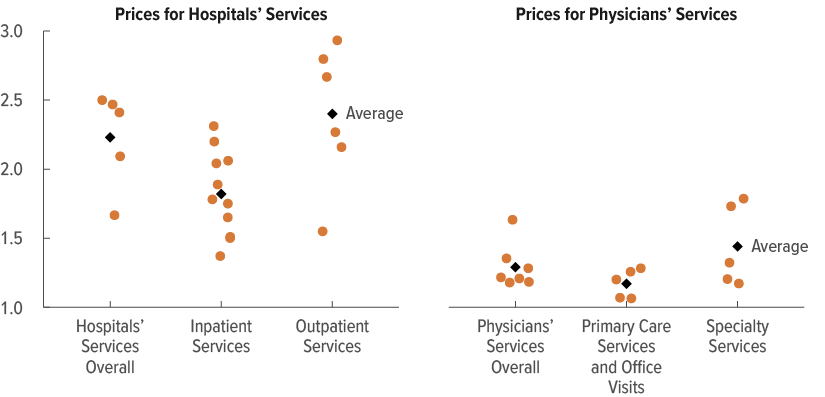

Figure 1–1 — Estimates of Commercial Insurers’ Prices for Providers Relative to the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program’s Prices

Multiple of Medicare FFS’s Prices

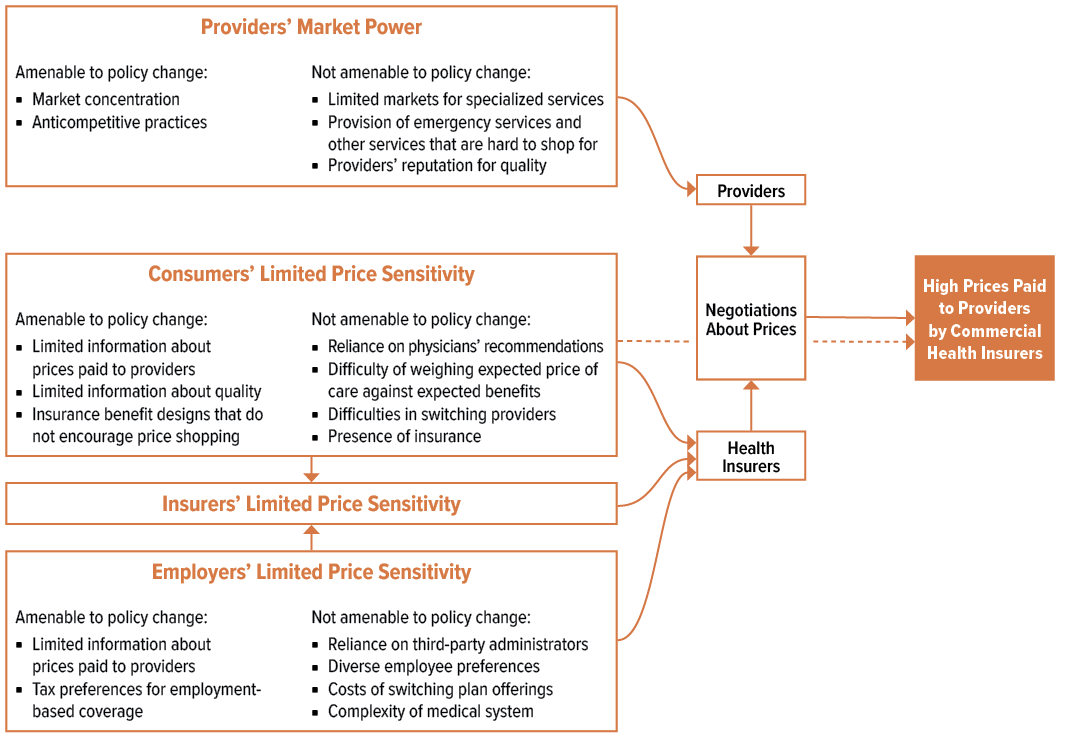

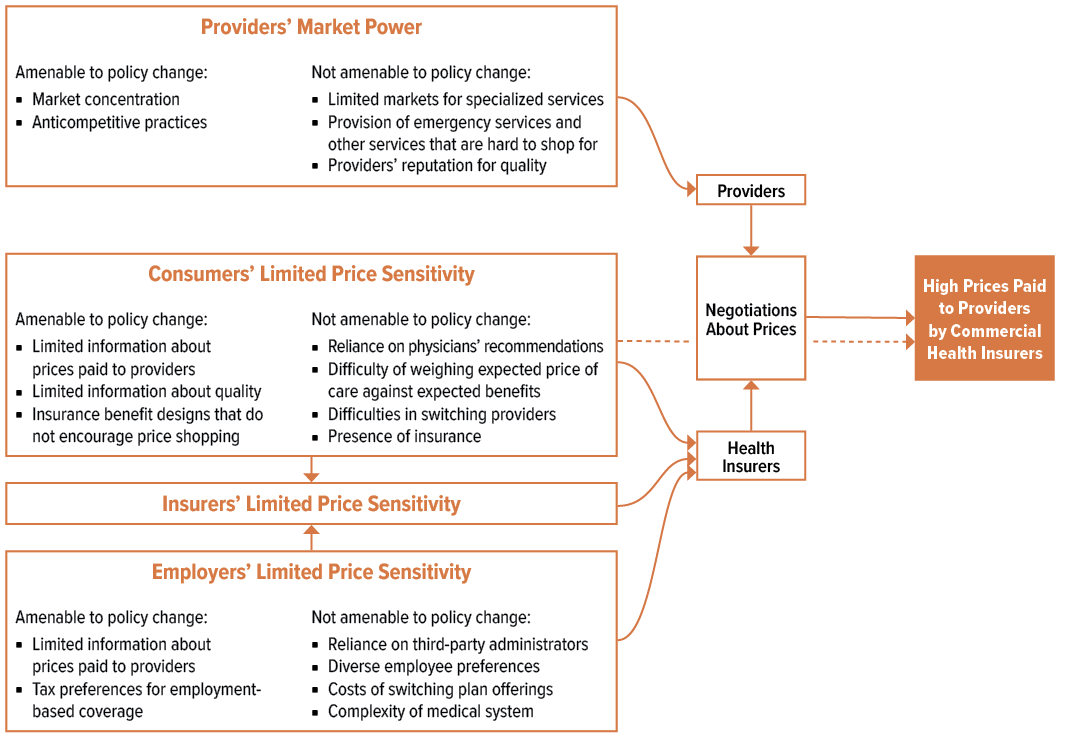

Figure 1–2 — Factors Contributing to the High Prices That Commercial Insurers Pay for Hospitals’ and Physicians’ Services

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION (excerpt)

Understanding the High Prices That Commercial Health Insurers Pay Providers [excerpt — US context]

This is an excerpt of the publication “Understanding the High Prices That Commercial Health Insurers Pay Providers”, with the title above.

This is the Chapter 1 of the report “Policy Approaches to Reduce What Commercial Insurers Pay for Hospitals’ and Physicians’ Services”, published by CBO (Congressional Budget Office), in September 2022.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

Phillip L. Swagel, Director

September 2022

Most people in the United States under age 65 are enrolled in a commercial health plan as their primary source of health insurance coverage.

In 2022, almost 160 million people obtained commercial insurance through an employer, and about 17 million purchased coverage themselves in the nongroup market.1

By several measures, the prices that commercial insurers pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services are high and rising.

Such price growth has consequences for individuals: It can lead to higher insurance premiums, lower wages, increases in cost-sharing requirements for patients, and reductions in the scope of insurance benefits.

Price growth also has consequences for the federal budget because it increases the federal government’s subsidies for commercial health insurance.

By several measures, the prices that commercial insurers pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services are high and rising.

Through its analysis and review of the research literature, the Congressional Budget Office has identified three main factors underlying the high prices paid by commercial insurers:

- providers’ market power,

- consumers’ limited sensitivity to the prices they pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services, and

- employers’ limited sensitivity to those prices.

… the CBO has identified three main factors underlying the high prices paid by commercial insurers: (1) providers’ market power, (2) consumers’ limited sensitivity to the prices they pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services, and (3) employers’ limited sensitivity to those prices.

A lack of price sensitivity among insurers, which primarily reflects the lack of sensitivity among consumers and employers, also contributes to high prices.

Most of the policy approaches that are the focus of this report would aim to lower the prices paid by commercial insurers by targeting one or more of those factors. (The policy approaches are discussed in Chapter 2.)

Levels, Trends, and Variation in Prices

Compared with the prices paid by the Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) program and by commercial insurers in other countries, the prices that commercial insurers in the United States pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services are high.

They also vary substantially among different areas and among providers in the same area.

Large variation in prices for the same or similar services can occur for many reasons, but it is often evidence of market failures — that is, conditions that result in the inefficient use of resources to purchase and deliver health care services.

Large variation in prices for the same or similar services can occur for many reasons, but it is often evidence of market failures — that is, conditions that result in the inefficient use of resources to purchase and deliver health care services.

In a recent literature review, CBO found that providers’ market power was a key reason for variation in the prices that commercial insurers pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services across the United States.2

Some evidence suggested that two other factors played a lesser role:

- the prices of inputs needed to deliver those services (such as the cost of supplies and materials, the wages of nurses and other staff, and the costs of medical facilities and equipment) and

- the quality of services.

… providers’ market power was a key reason for variation in the prices that commercial insurers pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services across the United States.

Some evidence suggested that two other factors played a lesser role: (1) the prices of inputs needed to deliver those services … and (2) the quality of services.

CBO’s analysis and review of the literature found no evidence that the share of providers’ patients covered by Medicare or Medicaid played any part in price variation in most settings.

Level of Prices

In recent years, commercial insurers paid higher prices, on average, for both hospitals’ and physicians’ services than Medicare FFS paid, but those price differences were substantially larger for hospitals’ services than for physicians’ services.

In recent years, commercial insurers paid higher prices, on average, for both hospitals’ and physicians’ services than Medicare FFS paid, but those price differences were substantially larger for hospitals’ services than for physicians’ services.

In a previous review of studies published between 2010 and 2020, CBO estimated that the prices that commercial insurers paid for hospitals’ services overall were more than twice the prices that Medicare FFS paid — 2.4 times Medicare FFS’s prices for hospitals’ outpatient services, on average, and 1.8 times those prices for hospitals’ inpatient services (see Figure 1–1).3

… the prices that commercial insurers paid for hospitals’ services overall were more than twice the prices that Medicare FFS paid — 2.4 times Medicare FFS’s prices for hospitals’ outpatient services, on average, and 1.8 times those prices for hospitals’ inpatient services

The average prices paid by commercial insurers for physicians’ services overall were 1.3 times the prices paid by Medicare FFS — 1.4 times Medicare FFS’s prices for specialty physicians’ services and 1.2 times those prices for primary care and office visits. (Those differences account for adjustments to prices paid by Medicare based on the setting in which a service is provided and the complexity of that service.)

Figure 1–1 — Estimates of Commercial Insurers’ Prices for Providers Relative to the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program’s Prices

Multiple of Medicare FFS’s Prices

On average, commercial insurers paid more than double the prices that Medicare FFS paid for hospitals’ services overall and about one-quarter more than Medicare FFS for physicians’ services overall.

In addition, several studies have concluded that the prices paid by commercial insurers in the United States are substantially higher than the prices paid by both private insurers and public health insurance programs in other advanced economies, on average.4

The authors of those studies found that spending for health care was much higher in the United States than in other countries despite similar inputs and levels of health care utilization, which indicates that U.S. prices are higher.5

Finally, several other studies have shown that the prices private insurers can negotiate to pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services in their Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care plans are substantially lower than the prices those same insurers pay for similar services in their commercial plans.

Those differences may be attributable in part to the bargaining power that insurers gain from the existence of those public programs.6

…several studies have concluded that the prices paid by commercial insurers in the United States are substantially higher than the prices paid by both private insurers and public health insurance programs in other advanced economies, on average

Growth of Prices

Between 2013 and 2018, commercial insurers’ prices for hospitals’ and physicians’ services combined grew at an average rate of 2.7 percent per year, CBO estimates.7

That growth rate was about 1 percentage point higher than average yearly inflation during that period, as measured by the gross domestic product price index.

By comparison, the prices paid by the Medicare FFS program, which are updated regularly by statute and regulation, increased at an average rate of 1.3 percent per year for an analogous set of services.

The rapid growth of prices paid by commercial insurers was the primary factor driving increases in those insurers’ spending per person.

Between 2013 and 2018, commercial insurers’ prices for hospitals’ and physicians’ services combined grew at an average rate of 2.7 percent per year, CBO estimates.

The rapid growth of prices paid by commercial insurers was the primary factor driving increases in those insurers’ spending per person.

Variation in Prices Among and Within Areas

Many studies have found substantial variation in the prices that commercial insurers pay in different geographic areas, to different providers in the same area, and even among different insurers for services provided by the same hospital or provider group.

In most studies, those findings have been based on prices for a narrowly defined or standardized service, such as a specific type of diagnostic imaging or knee replacement.

Many studies have found substantial variation in the prices that commercial insurers pay in different geographic areas, to different providers in the same area, and even among different insurers for services provided by the same hospital or provider group.

Some geographic variation in prices for the same service is to be expected given differences in the prices of inputs necessary to deliver care, such as the wages of nurses, doctors, and other staff.

Indeed, Medicare adjusts payments by geographic area to account for such differences.

However, the fact that price variation among commercial insurers greatly exceeds price variation in Medicare FFS suggests some degree of market inefficiency, including the ability of some providers to command prices far exceeding their costs.8

… the fact that price variation among commercial insurers greatly exceeds price variation in Medicare FFS suggests some degree of market inefficiency, including the ability of some providers to command prices far exceeding their costs

Moreover, those higher prices are typically not a result of cost shifting (that is, providers do not negotiate higher prices from commercial insurers in response to lower payments from public programs), according to an analysis and literature review by CBO.9

Factors That Lead to High Prices

The high prices that commercial insurers pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services result from several factors, primarily the market power of providers and the limited sensitivity of consumers and employers to those prices.

Other factors — such as providers’ input prices, the quality of their services, and the lower prices paid by public programs — have substantially less impact on prices, in CBO’s assessment. Limited price sensitivity on the part of insurers also contributes to high prices, but it mainly results from price insensitivity among consumers and employers.

The high prices that commercial insurers pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services result from several factors, primarily the market power of providers and the limited sensitivity of consumers and employers to those prices.

Other factors — such as providers’ input prices, the quality of their services, and the lower prices paid by public programs — have substantially less impact on prices, …

Those various factors limit insurers’ incentives to bargain for lower prices when they negotiate with providers.

In particular, providers with market power can credibly threaten to stay out of an insurer’s network and still maintain their market share, which strengthens their ability to negotiate higher prices with insurers.10

Insurers could push back against those higher prices, but their incentives to do so are lessened if the consumers and employers who purchase their plans are largely insensitive to prices.

Many of the policies that aim to reduce commercial insurers’ prices for hospitals’ and physicians’ services target the factors that underlie those prices.

However, lawmakers’ ability to influence prices by targeting those factors depends on whether the causes of those factors are amenable to change by federal policy (see Figure 1–2).

Figure 1–2 — Factors Contributing to the High Prices That Commercial Insurers Pay for Hospitals’ and Physicians’ Services

Providers’ Market Power

Among hospitals and physicians, the ability to raise prices above those that would prevail in a perfectly competitive market can stem from several sources, including the concentration of market share among only a few providers, contracts that reduce competition, and the status of particular providers.

Some of those sources of market power can be altered by changes in government policy, but others cannot.

Among hospitals and physicians, the ability to raise prices above those that would prevail in a perfectly competitive market can stem from several sources, including the concentration of market share among only a few providers, contracts that reduce competition, and the status of particular providers.

Some of those sources of market power can be altered by changes in government policy, but others cannot.

- Market Concentration

- Anticompetitive Contracts

- Providers’ Status (Reputation)

Market Concentration. The extent to which a few providers control a large share of a given market is an important source of market power for providers. As insurers and providers negotiate over prices for services, each side’s negotiating leverage is determined by the alternatives that the other side has to reaching an agreement. An insurer has more bargaining leverage if a provider has few good alternatives to being part of that insurer’s network. Similarly, a provider has more leverage if an insurer has few good alternatives to having that provider in its network. Controlling a large share of the market can increase market power for providers because it leaves insurers with fewer viable alternatives.

Markets for hospitals’ and physicians’ services in the United States have become more concentrated over time. For instance, the percentage of metropolitan statistical areas whose markets for primary care physicians were considered highly concentrated under the definition used by the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice increased from 20 percent in 2010 to 39 percent in 2016.11 The trend toward more consolidated markets partly reflects an increase in mergers among hospitals and consolidation of physicians’ practices into larger groups (which can also occur when hospitals acquire physicians’ practices). Attrition among smaller practices has also played a role, as solo physicians have retired and new physicians have joined larger practices.12

In addition, markets have become more concentrated than they would be otherwise because of barriers to entry. Some barriers are related to the fixed costs of establishing a hospital or receiving the training necessary to become a physician. Others, such as accreditation, are designed to protect patients. But others, such as noncompete clauses, are designed mainly to reduce providers’ ability to change jobs and compete against their former employer.13

The academic research that CBO reviewed consistently found a strong positive relationship between measures of market concentration for hospitals’ and physicians’ services and the prices paid by commercial insurers. Providers’ market concentration can be targeted by policies that slow the growth of concentration, make markets less concentrated, or both.

Anticompetitive Contracts. Established providers may take active measures to maintain or improve their market position by negotiating contracts with insurers that contain anticompetitive elements.

In many cases, those contracts restrict insurers from giving their enrollees incentives to use lower-priced or higher-quality providers.

Outlawing such clauses or limiting the circumstances in which they can be used would be ways to curb providers’ anticompetitive practices.

Providers’ Status. Providers gain market power in various ways, including by having a reputation for quality, by delivering highly specialized services, or by providing services that consumers do not typically shop for. (Such “unshoppable” services include emergency services and ambulance transport, which often need to be provided urgently, and anesthesiology and pathology services delivered in hospitals, which are ancillary to another service a patient is receiving.)

Those various sources of market power can give providers “must-have” status. Such status can increase providers’ negotiating leverage with insurers if the insurers believe that including those providers in their networks is essential for attracting consumers and employers to their plans.

Unlike other causes of market power, providers’ reputation and their delivery of specialized or unshoppable services are generally not amenable to change by government policy.

For example, given the small number of patients who use specialized services and the natural barriers to entry for certain specializations (such as the extensive training needed), it is more efficient for a smaller set of providers to deliver a larger volume of those services, which decreases the cost per service. In addition, the quality of specialized services is often improved when a smaller number of providers each deliver a larger volume of services.

Purchasers’ Limited Sensitivity to Prices

Another factor underlying the high prices paid by commercial insurers is consumers’ and employers’ limited sensitivity to the prices they pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services.

Limited price sensitivity on the part of insurers also contributes to those high prices, but in CBO’s assessment, it largely reflects the price insensitivity of the consumers and employers that are their customers.

Another factor underlying the high prices paid by commercial insurers is consumers’ and employers’ limited sensitivity to the prices they pay for hospitals’ and physicians’ services.

Limited price sensitivity on the part of insurers also contributes to those high prices, [but with a low impact]

Health Care Consumers. Prices for hospitals’ and physicians’ services tend to play a smaller role in consumers’ decisions about where to seek and purchase care than prices for other goods and services play in people’s other purchasing decisions. That limited price sensitivity largely reflects aspects of the way medical care is delivered in the United States that are not amenable to change by government policy, such as the following:

- Patients rely on the expert advice of physicians and other health care professionals when deciding what care to obtain.14 Providers generally do not prioritize saving money for patients or insurers, and they may benefit from referring patients to higher-priced providers. Such referrals may be particularly likely when the referring physicians and the other providers of ancillary services are employed by the same entity.

- Patients cannot easily weigh the expected price of getting care against the expected benefits it will provide, which makes it difficult for them to determine the value of a given service.

- Some patients are reluctant to switch to a lower-priced provider because establishing a relationship with a new provider can be laborious. For example, patients might have to request that their medical records be sent to the new provider — and even then, the new provider’s knowledge of the patients’ preferences and health history may be limited.

- Many patients are insensitive to prices because insurance shields them from most price variation. For instance, many patients pay a flat copayment for a given service, such as an office visit, regardless of the price the insurer pays to the provider. And in many cases, out-of-pocket maximums shield users of the highest-cost services from prices. Changes to the design of insurance benefits could make people more sensitive to prices, but patients’ coverage would still generally protect them from a large share of the costs of health care services. (See Appendix A for a discussion of how reducing tax preferences for employment-based insurance would encourage the use of insurance benefit designs that make people more sensitive to prices.)

Other sources of consumers’ price insensitivity reflect characteristics of the U.S. health care system or existing policies that are amenable to policy changes.

One such source is a lack of information about the prices and quality of services. Even when price information is readily available, it can be difficult for patients to interpret, for several reasons.

It is typically limited to a subset of individual services rather than to a bundle of services, such as all services related to a knee replacement.

In many cases, it is not presented in a way that accounts for patients’ insurance coverage, such as whether patients have a high-deductible health plan and how close they are to meeting their deductible.

And it requires consumers to interpret the information themselves, with little recourse to ask questions or gain additional information.

Other sources of consumers’ price insensitivity reflect characteristics of the U.S. health care system or existing policies that are amenable to policy changes.

One such source is a lack of information about the prices and quality of services.

Even when price shopping is possible, consumers may not select the lowest-priced provider.

In markets where the quality of services is uncertain and where poor quality can have significant consequences, patients may view higher prices as a sign of higher quality.

Such behavior may be reinforced by insurance plans that do not reward patients for using lower-priced providers. (Plans can create such rewards by, for example, using reference pricing, in which the insurer pays a flat rate for a given service and patients bear the additional cost of going to a higher-priced provider).

Consumers’ price insensitivity has two key implications for the prices paid to providers.

First, for any given set of negotiated prices, it causes patients to use higher-priced providers, on average, than they would if price were a greater consideration.

Second, it makes insurers — whose plans partly reflect consumers’ (and employers’) preferences and values — less sensitive to high and rising prices when negotiating with providers.

Employers. Because employers provide coverage to most people with commercial health insurance, their decisions determine the options that many people have for coverage and the prices they face when seeking care. In many cases, those prices are high because employers, like consumers, tend to be insensitive to prices for hospitals’ and physicians’ services. That insensitivity manifests in two ways. First, other than through any effects on premiums, the prices paid to providers typically have little effect on employers’ choice of health insurance plans. Second, employers typically rely on other entities, such as benefit consultants, to negotiate with insurers.

In some cases, employers’ insensitivity to prices for hospitals’ and physicians’ services stems from the same sources as consumers’ price insensitivity. For example, the information about those prices that is available to employers tends to be limited, even though such prices affect how much employers or their employees pay for premiums. That incomplete information results partly from employers’ reliance on insurers or other entities to negotiate prices and partly from employers’ difficulty observing the prices negotiated between other employers and providers, which until recently have been considered trade secrets. Moreover, because the share of premiums that employers pay is generally excluded from their workers’ taxable income, employers have less incentive to seek more complete information.

In other cases, the reasons for employers’ price insensitivity differ from the reasons for consumers’ price insensitivity and are less amenable to change by government policy. For example, employers’ decisions about insurance coverage reflect the diverse preferences of their employees, and employers may prioritize the preferences of workers who would be adversely affected by a change in insurance plans or networks.15 Such preferences can make it challenging for employers to lower the prices paid to providers by, for instance, offering plans that exclude high-priced providers or have narrow networks, particularly when employers are trying to arrange coverage for workers spread across broad geographic areas. Employers may also be concerned that introducing plans with new benefit designs or reduced access to certain providers or benefits would upset their workers and make the employers less competitive in the labor market.16 Such considerations — along with the administrative complexity of switching plans — make it costly for employers to change the plans they offer to include benefit designs that encourage the use of lower-priced providers.

Most employers’ responses to the prices paid to providers are also blunted because employers lack the expertise and time needed to navigate a complex medical system.

In CBO’s assessment, small employers tend to face the greatest challenges in navigating that system, but larger employers with more resources face difficulties as well. As a result, employers’ roles in designing provider networks for plans, negotiating prices, and processing claims are almost always outsourced to consultants or third-party administrators. Those entities do not realize the full gains from negotiating lower prices, so they have little incentive to do so.

Health Insurers. The persistently high and rising prices paid by commercial insurers for hospitals’ and physicians’ services could also be explained by insurers’ own insensitivity to the prices they pay. But in CBO’s assessment, that insensitivity is largely a reflection of consumers’ and employers’ price insensitivity. Demand for health insurance tends to be inelastic, meaning that consumers and employers do not reduce insurance purchases by a large amount, or at all, when premiums rise to reflect higher prices. If those groups were more sensitive to prices and premiums, insurers would be more likely to take steps to reduce or slow the growth of the prices they pay providers to avoid losing market share.

Insurers’ limited sensitivity to prices for hospitals’ and physicians’ services may also stem in part from their ability to increase revenues and profits when those prices rise. For example, insurers that provide only administrative services to self-insured employers may set their fees as a percentage of spending on claims; if everything else stayed the same, higher prices would increase health care spending and thus those insurers’ profits.17

In addition, insurers that sell coverage in the fully insured and nongroup markets may accept paying higher prices to providers because of legal requirements implemented in 2012 …

… that specify the minimum percentage of premiums an insurer must spend on health care claims and quality-improvement activities. (That percentage is known as the medical loss ratio, or MLR.)18

In those markets, some insurers could see their revenues and profits increase as the prices paid to providers rose.

For instance, if enrollment remained constant, an insurer that kept its loss ratio equal to the required minimum could pay higher prices to providers, raise its premiums, and realize additional profits.

The insurer could also achieve those additional profits while keeping its loss ratio at the required minimum by allowing spending to increase through more utilization of health care services by its enrollees.

Studies suggest that insurers’ responses to MLR requirements are largely consistent with increases in utilization rather than in prices.19 (For a discussion about eliminating MLR requirements, see Appendix A.)

Insurers’ ability to negotiate lower prices with providers is also limited in markets that have more competing insurers.

In those more competitive insurance markets, insurers’ bargaining power is lessened relative to that of providers, and insurers may be reluctant to demand steep discounts because doing so could lead providers to drop out of their network.

Many other areas have less competitive insurance markets; there, dominant insurers could use their market power to negotiate lower prices for providers.20

In those markets, however, a dominant insurer whose medical loss ratio was above the required threshold would have little incentive to pass on the savings from lower prices by reducing premiums, because it would face little pressure from competing insurers to do so.21

References and additional information:

See the original publication: https://www.cbo.gov