health transformation institute (HTI)

the most comprehensive knowledge portal for health transformation

Joaquim Cardoso MSc*

Founder and Chief Researcher and Editor

November 27, 2022

MSc* from London Business School — MIT Sloan Masters Program

This is a republication of the article “Unexpected Result: COVID-19 Vaccination Improves Effectiveness of Cancer Treatment”, with the title above. The 2nd part of the post, contains a republication of the original article.

SciTechDaily

By UNIVERSITY OF BONN

NOVEMBER 25, 2022

Clinical study on nasopharyngeal cancer with an unexpected result.

Patients with nasopharyngeal cancer are often treated with drugs that activate their immune system against the tumor.

Scientists feared that vaccination against COVID-19 could reduce the success of cancer treatment or cause severe side effects — until now.

A recent study now gives the all-clear in this regard.

According to the study, the cancer drugs actually worked better after vaccination with the Chinese vaccine SinoVac than in unvaccinated patients.

According to the study, the cancer drugs actually worked better after vaccination with the Chinese vaccine SinoVac than in unvaccinated patients.

The results of the study, which was conducted by the Universities of Bonn and Shanxi in the People’s Republic of China, are published as a “Letter to the editor” in the journal Annals of Oncology, but are already available online.

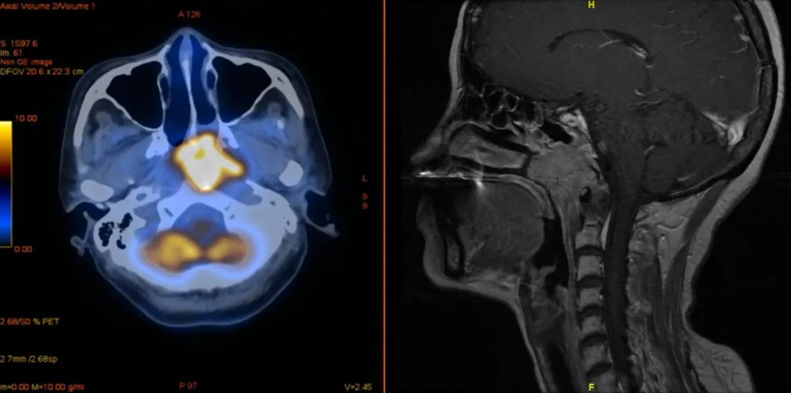

Nasopharyngeal cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the nasopharynx. The nasopharynx is the upper part of the throat behind the nose. An opening on each side of the nasopharynx leads into the ear.

Many cancer cells are capable of subverting the body’s immune response.

They do this by pushing a kind of button on the immune cells, the PD-1 receptor.

In this way, they effectively shut down these endogenous defense forces.

Drugs can be used to block PD-1 receptors. This enables the immune system to fight the tumor more effectively.

Drugs can be used to block PD-1 receptors. This enables the immune system to fight the tumor more effectively.

Vaccination against COVID also stimulates the immune response, involving the PD-1 receptor.

“It was feared that the vaccine would not be compatible with anti-PD-1 therapy,” explains Dr. Jian Li of the Institute of Molecular Medicine and Experimental Immunology (IMMEI) at the University Hospital Bonn.

“This risk is especially true for nasopharyngeal cancer, which, like the SARS Cov-2 virus, affects the upper respiratory tract.”

Together with cooperation partners from the People’s Republic of China, the bioinformatician has now investigated whether this concern is justified.

More than 1,500 patients treated in 23 hospitals from all over China participated in the analysis.

Such multi-center studies are considered to be particularly informative because the participants are very diverse and, moreover, the results are not distorted by regional characteristics.

Vaccinated patients responded better to cancer therapy

A subset of 373 affected individuals had been vaccinated with the Chinese COVID-19 vaccine SinoVac.

“Surprisingly, they responded significantly better to anti-PD-1 therapy than the unvaccinated patients,” explains Prof. Dr. Christian Kurts, Director of IMMEI and member of the Transdisciplinary Research Area “Life & Health” and the Cluster of Excellence ImmunoSensation.

“Furthermore, they did not experience severe side effects more often.” The researchers cannot say why the treatment was more successful after vaccination.

“We assume that vaccination activates certain immune cells, which then attack the tumor,” says Prof. Dr. Qi Mei of Shanxi University Hospital. “We will now investigate this hypothesis further.”

“Surprisingly, they responded significantly better to anti-PD-1 therapy than the unvaccinated patients …furthermore, they did not experience severe side effects more often.

“We assume that vaccination activates certain immune cells, which then attack the tumor,” … “We will now investigate this hypothesis further.”

Nasopharyngeal cancer is quite rare in this country. In southern China and other countries in Southeast Asia, however, the disease is widespread.

One of the suspected reasons for this is the frequent use of air conditioning in the hot and humid regions.

Nasopharyngeal cancer is quite rare in this country. In southern China and other countries in Southeast Asia, however, the disease is widespread.

Nutritional factors also appear to play an important role.

In Taiwan, nasopharyngeal cancer is now considered one of the leading causes of death among young men.

In Taiwan, nasopharyngeal cancer is now considered one of the leading causes of death among young men.

Reference:

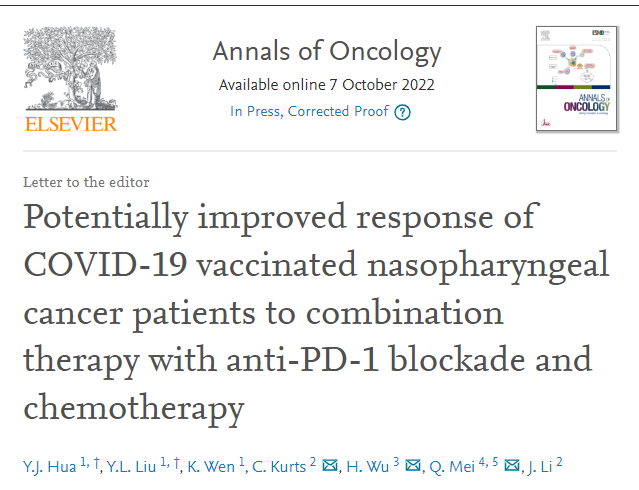

“Potentially improved response of COVID-19 vaccinated nasopharyngeal cancer patients to combination therapy with anti-PD-1 blockade and chemotherapy” by Y.J. Hua, Y.L. Liu, K. Wen, C. Kurts, H. Wu, Q. Mei and J. Li, Annals of Oncology.

DOI: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.10.002

Participating institutions and funding:

In addition to the University of Bonn and the University Hospital, Shanxi Medical University and Tongji Medical College were involved in the work. The researchers also collaborated with a number of clinics throughout China. The study was funded by the Sino-German Center for Research Promotion (SGC), the DFG Cluster of Excellence ImmunoSensation², and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

Potentially improved response of COVID-19 vaccinated nasopharyngeal cancer patients to combination therapy with anti-PD-1 blockade and chemotherapy

Annals of Oncology

Y.J.Hua 1, Y.L.Liu 1, K.Wen 1, C.Kurts 2, H.Wu 3 Q.Mei 4 5 J.Li 2

7 October 2022

Anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (anti-PD-1) treatment was demonstrated to be effective in nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) patients.1

During the COVID-19 pandemic, concern was raised whether anti-PD-1 treatment can interfere with COVID-19 vaccination in NPC patients, although our previous study showed that the efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 treatment was not reduced in general cancer patients vaccinated with SinoVac.2

NPC affects the upper respiratory tract, where the COVID-19 infection takes place.

Possible interferences between anti-PD-1 treatment and COVID-19 vaccination in NPC patients remain elusive.

Our study aims to fill this gap.

A total of 2134 NPC patients were screened from 35 hospitals beginning on 28 January 2021.

Eligible participants met these criteria: (i) confirmed NPC; (ii) received ≥1 dose of anti-PD-1 treatment; (iii) available medical record and willingness for follow-up.

Clinical and demographical data were collected at the enrollment. The last date of follow-up was 25 June 2022.

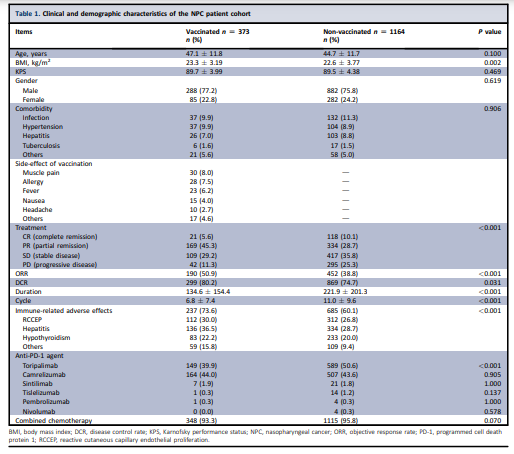

A total of 1537 NPC patients met the criteria and were included from 23 hospitals (median age 45 years, 23.9% female; Table 1).

All patients were in a recurrent metastatic (RM) stage and received first-line anti-PD-1 therapy at the time of relapse or diagnosis of metastasis, with most receiving concomitant anti-PD-1 therapy and chemotherapy.

The most frequent immune-related adverse events (irAEs) include hepatitis (470; 30.6%) and reactive cutaneous capillary endothelial proliferation (424; 27.6%).

The outcomes showed that

- 140 (9.1%) patients achieved complete remission,

- 503 (32.7%) partial remission,

- 526 (34.2%) stable disease, and

- 337 (21.9%) progressive disease (Table 1).

In this cohort, 373 (24.3%) patients were vaccinated with SinoVac,3 and were defined as the vaccinated subgroup.

Median interval between vaccination and first dose of anti-PD-1 treatment was 105.0 days (range −24 to 154 days).

The remaining 1164 (75.7%) were not vaccinated against COVID-19 and defined as the non-vaccinated subgroup.

Compared with the non-vaccinated subgroup, vaccinated patients showed a higher objective response rate (ORR 59.0% versus 38.8%, P < 0.001, Table 1) and disease control rate (DCR 80.2% versus 74.7%, P = 0.031) following anti-PD-1 treatment, were more likely to experience mild irAEs (73.6% versus 60.1%, P < 0.001) and mild vaccine-related adverse effects (21.7% versus 8.2%, P < 0.001).

No significant difference in severe irAEs was observed between both subgroups.

Through propensity score matching (ratio of 2 : 1) for age, gender, Karnofsky performance status (KPS) and body mass index (BMI) in this cohort, 1119 patients were selected for further analysis.

Compared with the matched non-vaccinated subgroup, matched vaccinated patients still had a higher ORR (59.0% versus 35.7%, P < 0.001) and DCR (80.2% versus 72.5%, P = 0.018), and to more frequently experience mild irAEs (73.6% versus 61.1%, P < 0.001).

No significant differences in severe irAEs were observed between both matched subgroups (4.9% versus 4.1%, P = 0.482).

NPC is characterized by peritumoral immune infiltration in the upper respiratory tract.4

The tumor microenvironment (TME) in NPC may recruit myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)5 to escape immunotherapy, but this might also reduce the effect of COVID-19 vaccination.

Our results showed that the safety of the combination of anti-PD-1 treatment and chemotherapy was not reduced for NPC patients during the vaccination period, and the efficacy of combination of anti-PD-1 treatment and chemotherapy was significantly improved for vaccinated NPC patients.

Possible reasons include:

(i) CD4+ T cells might be activated and enter into the TME during vaccination, preventing MDSCs or regulatory T cells (Tregs) recruitment5; (ii) exhausted CD8+ T cells might be reactivated in the TME during vaccination, facilitating immunotherapy.6

Future studies are warranted to elucidate underlying mechanisms.

The association of COVID-19 vaccination with increased efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy with chemotherapy in RM NPC is interesting, but needs to be validated in a larger cohort study.

References

See the original publication https://www.sciencedirect.com

About the authors & affiliations

Y. J. Hua 1,y , Y. L. Liu 1,y , K. Wen 1 , C. Kurts 2*, H. Wu 3*, Q. Mei 4,5* & J. Li 2

1 Department of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Guangzhou, China;

2 Institute of Molecular Medicine and Experimental Immunology, University Clinic of Rheinische FriedrichWilhelms-University, Bonn, Germany;

3 Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences, Tongji Shanxi Hospital, Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi;

4 Cancer Center, Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Tongji Shanxi Hospital, Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi;

5 Department of Oncology, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, People’s Republic of China