Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic

This is an excerpt of the paper below, focusing on the DISCUSSION & RECOMMENDATIONS of the document.

The Lancet

COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators

October, 8, 2021

Main findings of the study

- First global estimates of impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in 2020 suggests additional 53 million cases of major depressive disorder and 76 million cases of anxiety disorders were due to the pandemic.

- Women and younger people were the most affected by major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in 2020.

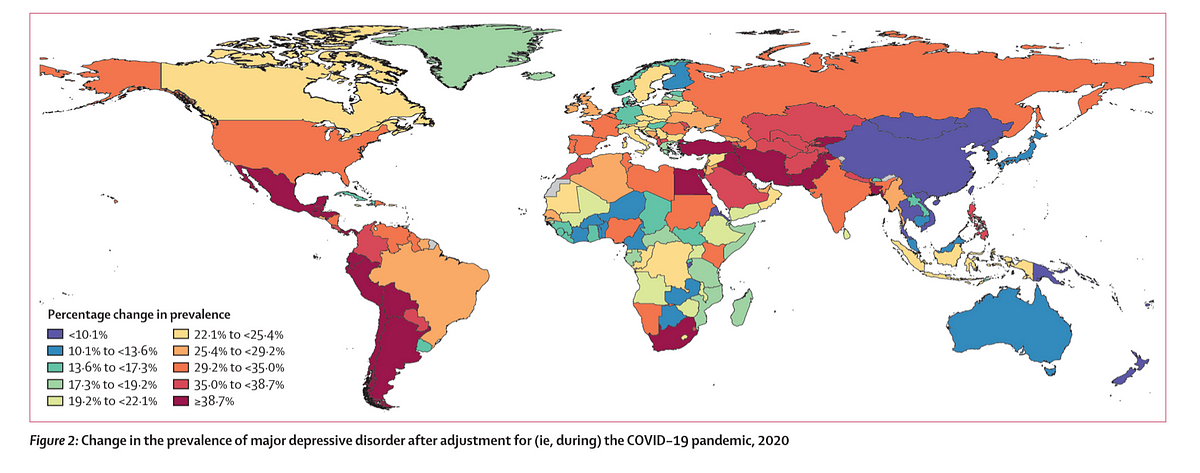

- Countries hit hardest by the pandemic in 2020 had the greatest increases in cases of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders.

- The authors call for urgent action by governments and policy makers to strengthen mental health systems globally to meet increased demand due to the pandemic.

Key recommendations (copied from the end of the Discussion chapter)

- Unfortunately, even before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders were leading causes of disease burden, with the mental health-care system in most countries being under-resourced and disorganised in their service delivery.

- Therefore, tackling this increased mental health burden will present immediate challenges in most nations, but it is also an opportunity for countries to broadly reconsider their mental health service response.

- Recommended mitigation strategies should incorporate ways to promote mental wellbeing and target determinants of poor mental health exacerbated by the pandemic, as well as interventions to treat those who develop a mental disorder.

- A mixture of digital, telehealth, and face-to-face services have been suggested that can be tailored to individual need

- Taking no action in the face of the estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence and burden of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders should not be an option.

Background

Before 2020, mental disorders were leading causes of the global health-related burden, with depressive and anxiety disorders being leading contributors to this burden.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has created an environment where many determinants of poor mental health are exacerbated.

The need for up-to-date information on the mental health impacts of COVID-19 in a way that informs health system responses is imperative. In this study, we aimed to quantify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence and burden of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders globally in 2020.

Added value of this study

This study is the first to quantify the prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders by age, sex, and location globally. We compiled available evidence of the change in the prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. We then developed a model to estimate the prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders by age, sex, and location on the basis of available indicators of the location-specific impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. We then used prevalence to estimate the burden of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Implications of all the available evidence

We found that depressive and anxiety disorders increased during 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, depressive and anxiety disorders featured as leading causes of burden globally, despite the existence of intervention strategies that can reduce their effects. Meeting the added demand for mental health services due to COVID-19 will be difficult, but not impossible. Mitigation strategies should promote mental wellbeing and target determinants of poor mental health exacerbated by the pandemic, as well as interventions to treat those who develop a mental disorder.

Other points

See the original publication

Discussion (focus of this excerpt)

In this study, we estimated a substantial increase in the prevalence and burden of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is, to our knowledge, the first study to systematically identify and analyse population mental health survey data and quantify the resulting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of these two disorders by location, age, and sex in 2020.

Increases in the prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders during 2020 were both associated with

- increasing SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and

- decreasing human mobility.

These two COVID-19 impact indicators incorporated the combined effects of the spread of the virus, lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, decreased public transport, school and business closures, and decreased social interactions, among other factors. We estimated that countries hit hardest by the pandemic during 2020 had the greatest increases in prevalence of these disorders.

The two COVID-19 impact indicators used in our model should not be interpreted as risk factors for major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. The risk factor of interest was the COVID-19 pandemic, with these two indicators acting as proxies for the effect of COVID-19 in the population.

Increases in the prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders during 2020 were both associated with (1) increasing SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and (2) decreasing human mobility.

The COVID-19 pandemic is occurring against a complex backdrop of a range of social determinants of mental health, as well as well known inequalities within these determinants.

- The greater increase in disorder prevalence among females than among males, which resulted in an even greater sex difference in prevalence than before the pandemic, was anticipated because females are more likely to be affected by the social and economic consequences of the pandemic. 17 , 18 , 19

- Additional carer and household responsibilities due to school closures or family members becoming unwell are more likely to fall on women. 17

Women are more likely to be financially disadvantaged during the pandemic due to lower salaries, less savings, and less secure employment than their male counterparts. 17 , 18 , 19 They are also more likely to be victims of domestic violence, the prevalence of which increased during periods of lockdown and stay-at-home orders. 20 , 21

We also estimated greater change in the prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders among younger age groups than among older age groups. UNESCO declared COVID-19 to be the most severe disruption to global education in history, estimating 1·6 billion learners in over 190 countries to be fully or partially out of school in 2020. 22

With school closures and wider social restrictions in place, young people have been unable to come together in physical spaces, affecting their ability to learn and for peer interaction.

Furthermore, young people are more likely to become unemployed during and following economic crises than older people. 23

Our study is not the first to show how population shocks (ie, unexpected or unpredictable events that disrupt the environmental, health, economic, or social circumstances within a population) can increase the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders. In their review of mental health outcomes after the economic crisis in 2009, Frasquilho and colleagues 24 identified several studies showing an increase in common mental disorders in the general population.

After the 2009 financial crisis in Greece, point prevalence of major depressive episodes increased from 3·3% (95% UI 3·1–3·5) in 2008 to 6·8% (6·4–7·2) in 2009 and 8·2% (8·1–8·3) in 2011. 25 Survey respondents reporting serious economic hardship were most at risk of developing a major depressive episode. 25 , 26

Similarly, after the 2008 financial crisis in Hong Kong, past-year prevalence of major depressive episodes increased from 8·2% (95% UI 7·2–9·2) in 2007 to 12·5% (11·0–13·9) in 2009. 27

The extent of the increase in prevalence differed across studies, which might be due to study or population characteristics or different combinations of health and socioeconomic determinants of poor mental health, or a combination of these factors.

Another point of difference is the time period over which the impact of the shock is measured. This period might be a single point in time, weeks or months, or, as in our analysis, an average over the course of a longer period (eg, a year) during which there would have been fluctuating effects from the pandemic (ie, the shock).

Both major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders increase the risk of other diseases and suicide. 28 , 29 In their time-series analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on suicide rates across 21 high-income and middle-income countries, Pirkis and colleagues 30 found no significant increases in suicide rates between April and July, 2020.

This finding raises the question of whether or not the increased prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders we found was accompanied by a significant increase in suicide rates. We have insufficient data to draw any conclusions on this matter. Pirkis and colleagues 30 relied on data in the first few months of the pandemic, which might have been too early in the pandemic to detect an association between a new diagnosis of major depressive disorder or anxiety disorders and suicide.

Suicide trends might vary over extended periods, and as we progress through different phases of the pandemic the full scale of economic consequences and their effects will emerge, and their subsequent effects on suicide trends. For example, Tanaka and Okamota 31 found that, although suicide rates in Japan decreased by 14% during the first 5 months of the pandemic (February to June, 2020), they then increased by 16% (between July and October, 2020), with a larger increase among females and younger populations than among males and older populations.

Both major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders increase the risk of other diseases and suicide.

Even before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders (and mental disorders overall) were among the leading causes of health burden globally, with the mental health system in most countries being under-resourced and disorganised, despite evidence that effective prevention and intervention tools exist. 2 , 3 , 32 , 33

Even before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders (and mental disorders overall) were among the leading causes of health burden globally …

… with the mental health system in most countries being under-resourced and disorganised, despite evidence that effective prevention and intervention tools exist.

Meeting the added demand for mental health services due to COVID-19 will be difficult. Strategies to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2, such as physical distancing and restricted travel, have made it more difficult to acquire medication, attend treatment facilities, and receive in-person care.

In some settings, outpatient and inpatient services have been interrupted or resources redirected to treat those with COVID-19. 4 , 34 , 35 , 36

In other settings, individuals have become less likely to seek care for their mental health issues than before the pandemic because of concerns about becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the process. 4 , 34, 35 , 36

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a greater urgency for governments and policy makers to strengthen their mental health systems, and now with the added priority of integrating a mental health response within their COVID-19 recovery plan.

In the wake of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence and burden of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders, taking no action cannot be an option.

Resources exist to guide the development of mitigation strategies for reducing the mental health burden imposed by COVID-19.

These resources include strategies that make efficient use of already limited resources, consider the local context and vulnerable populations, and prioritise key principles such as inclusivity, stigma reduction, and human rights. 4 , 34 , 35 , 36

Strategies should promote mental wellbeing and target determinants of poor mental health exacerbated by the pandemic and interventions to treat those who develop a mental disorder. 4 , 34 , 35 , 36

They should consider public health messaging about the mental health impacts of COVID-19, how individuals can best manage their mental health, and well defined pathways to assessment and service access.

A mixture of digital, telehealth, and face-to-face services have been suggested that can be tailored to individual need. 4 , 34 , 35 , 36

There is already encouraging emerging evidence of the implementation of some of these strategies; 4 however, the full effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are still unfolding in many countries, with most programmes implemented under a public health emergency, with little capacity to fully assess their performance.

Here, we estimated the change in disorder prevalence in 2020 using the best data at our disposal, but these data will continue to be updated throughout the different phases of the pandemic. This ongoing work will also explore ways to improve the following limitations in the analyses reported here. First, we were limited by the data available to consistently measure the effect of COVID-19 across all GBD locations using our choice of COVID-19 indicators.

Human mobility and SARS-CoV-2 infection rates are unlikely to have captured the full impact of the pandemic on mental health across all countries. The precision in these two indicators can be improved, for example, in countries where infection rates are not consistently measured or reported. Reliance on mobile phone tracking technology to monitor human mobility will also not be accurate in locations where subgroups of the population (eg, people of low socioeconomic status) have little or no mobile phone use. Some subgroups might not be able to reduce their mobility because of their employment type and might be more prone to infection, and so reductions in human mobility might be exaggerated in these locations. As we progress through the pandemic and the full economic effects on some populations emerge, re-evaluation of available indicators will be important. For example, we made no distinction in prevalence between those with and without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection within the population. Emerging evidence suggests people with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (sometimes known as long COVID) might develop depressive and anxiety disorder symptoms, 37 , 38 and so prevalence of long COVID might be a potential indicator in future work. Second, we found very few surveys that met our inclusion criteria from low-income and middle-income countries, meaning that findings from our regression analysis might be less generalisable to these locations.

For example, we estimated large increases in prevalence within Latin America and the Caribbean, north Africa and the Middle East, and south Asia, despite not finding any surveys from these super-regions that met our inclusion criteria. Given the absence of high quality data for most countries, and the wide UIs around our estimates, we emphasise caution against extrapolating direct rankings between countries and territories. Our leave-one-country-out cross-validation analysis showed that although our estimates are generally within the bounds of uncertainty for re-predicting data for missing locations, the relative rankings of locations were affected by data availability. Precise rankings between countries and territories would require substantially more high quality data and improved data coverage globally. Third, most surveys in our dataset used symptom scales that only estimate probable cases of depressive and anxiety disorders. Where these scales were used, we assumed the predictive validity of symptom scales in diagnosis via established thresholds remained constant between before and during the pandemic. However, this assumption has the potential to bias our estimates. For example, high scores on anxiety disorder symptom scales might reflect a natural psychological and physiological reaction to a perceived threat (ie, the COVID-19 pandemic) rather than a probable anxiety disorder. At the time of publication, not enough data were available to assess this assumption. We identified only three diagnostic mental health surveys that had been done since the beginning of the pandemic. Increases in prevalence were observed in two of the three diagnostic surveys. 39 , 40 The study that did not report an increased prevalence was conducted in one specific city in Norway (Trondheim) using very small cross-sectional samples. 41

The authors of this study also reported that the shift from face-to-face to telephone survey administration occurred at the onset of the pandemic, which might have affected interviewers’ ability to identify mental disorders, especially in the early stages of this shift when they were less experienced with telephone survey administration.

The paucity of diagnostic surveys conducted during the pandemic also meant that we were unable to explore its effect on the severity distribution of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. We estimated prevalent cases of each disorder but could not assess how existing cases changed in their severity. Existing cases might have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, while novel cases might have had milder disorder severity. For the burden analysis presented, we had to assume that the severity distribution of both existing and new cases remained unchanged from before the COVID-19 pandemic. Fourth, many studies needed to be excluded from our systematic review because of reliance on convenience sampling strategies (eg, snowball sampling), case definitions that did not adhere to internationally accepted definitions for mental disorders, and use of survey instruments for which no comparable pre-pandemic estimate was available. Given the paucity of studies using random sampling of the general population, we took advantage of studies using market research and quota sampling during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that cross-sectional (but not longitudinal) studies that used market research quota sampling significantly over-estimated the increase in disorder prevalence. Samples obtained via this method might be more prone to mental disorders than the random samples that informed their pre-pandemic baseline estimates. We also found instruments that captured symptoms of both depressive and anxiety disorders combined overestimated the increase in prevalence of anxiety disorders, but not major depressive disorder. This could be because they captured more new depressive disorder cases than anxiety disorder cases. We hope that the data standards set for this analysis will guide decisions in the field for future mental health surveys done as a response to COVID-19 or other population shocks. Fifth, prevalences of mental disorders other than major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders might have also been affected by COVID-19. For instance, emerging evidence suggests that other disorders such as eating disorders have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic but these data have yet to be appropriately assessed. 42

Most of the available scientific literature focuses on changes in symptoms of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder as a result of COVID-19 because these are historically more sensitive to population shocks.

As new mental health surveys are undertaken, the effect of COVID-19 on other disorders will need to be quantified. The methodological framework we have developed can be adapted to other mental disorders. It can also be adapted to measure other population shocks on prevalence and disease burden.

At the time of writing this Article, the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing and its full impact on mental health outcomes is not known.

We continue to observe shifts in SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and human mobility as lockdown and stay-at-home orders are re-implemented or eased and COVID-19 vaccination programmes are rolled out. Our work is ongoing and will continue to be updated over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. To inform this ongoing work, high quality surveys conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic are needed within regions that are not represented by available data. Researchers planning surveys during the pandemic should strive to align their sample representation and measures of mental health with existing pre-pandemic baseline estimates to ensure appropriate comparable data from before and during the pandemic. Where feasible, researchers should consider including diagnostic measures of mental disorders, alongside widely used screening questionnaires (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 or General Anxiety Disorder-7). With the addition of more estimates derived via diagnostic instruments, we could explore the robustness of (or correct for) our assumption that the predictive validity of screening questionnaires for diagnosis of probable cases is unchanged by the pandemic, and explore any shifts in the severity distribution among individuals diagnosed with major depressive disorder or anxiety disorders.

Unlike other population shocks, COVID-19 has become global, disrupting many aspects of life for most, if not all, of the world’s populations.

Our analysis suggests that the impacts on the prevalence and burden of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders were substantial, particularly among females and younger populations.

Ongoing and additional mental health surveys are necessary to quantify the duration and severity of this impact.

Unfortunately, even before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders were leading causes of disease burden, with the mental health-care system in most countries being under-resourced and disorganised in their service delivery.

Therefore, tackling this increased mental health burden will present immediate challenges in most nations, but it is also an opportunity for countries to broadly reconsider their mental health service response.

Recommended mitigation strategies should incorporate ways to promote mental wellbeing and target determinants of poor mental health exacerbated by the pandemic, as well as interventions to treat those who develop a mental disorder.

Taking no action in the face of the estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence and burden of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders should not be an option.

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic

The Lancet

COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators

October, 8, 2021

About the authors

Authors List

- Damian F Santomauro

- Ana M Mantilla Herrera

- Jamileh Shadid

- Peng Zheng

- Charlie Ashbaugh

- David M Pigott

- Cristiana Abbafati

- Christopher Adolph

- Joanne O Amlag

- Aleksandr Y Aravkin

- Bree L Bang-Jensen

- Gregory J Bertolacci

- Sabina S Bloom

- Rachel Castellano

- Emma Castro

- Suman Chakrabarti

- Jhilik Chattopadhyay

- Rebecca M Cogen

- James K Collins

- Xiaochen Dai

- William James Dangel

- Carolyn Dapper

- Amanda Deen

- Megan Erickson

- Samuel B Ewald

- Abraham D Flaxman

- Joseph Jon Frostad

- Nancy Fullman

- John R Giles

- Ababi Zergaw Giref

- Gaorui Guo

- Jiawei He

- Monika Helak

- Erin N Hulland

- Bulat Idrisov

- Akiaja Lindstrom

- Emily Linebarger

- Paulo A Lotufo

- Rafael Lozano

- Beatrice Magistro

- Deborah Carvalho Malta

- Johan C Månsson

- Fatima Marinho

- Ali H Mokdad

- Lorenzo Monasta

- Paulami Naik

- Shuhei Nomura

- James Kevin O’Halloran

- Samuel M Ostroff

- Maja Pasovic

- Louise Penberthy

- Robert C Reiner Jr

- Grace Reinke

- Antonio Luiz P Ribeiro

- Aleksei Sholokhov

- Reed J D Sorensen

- Elena Varavikova

- Anh Truc Vo

- Rebecca Walcott

- Stefanie Watson

- Charles Shey Wiysonge

- Bethany Zigler

- Simon I Hay

- Theo Vos

- Christopher J L Murray

- Harvey A Whiteford

- Alize J Ferrari

Originally published at https://www.thelancet.com

Originally published at https://www.thelancet.com.