institute for continuous

health transformation

Joaquim Cardoso MSc

Senior Advisor for Continuous Health Transformation

and Digital Health

January 10, 2023

Executive Summary

- The COVID-19 pandemic persists with vaccine hesitancy and refusal impeding the effectiveness of the vaccines.

- The survey of 23 countries in 2022 aimed to track trends in global vaccine acceptance, profile attitudes towards recently available COVID-19 boosters and pharmaceutical treatments and assess attitudes towards factors that contribute to ongoing hesitancy such as mistrust in government and health authorities, concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy, age, and minority race or ethnicity.

- The survey also aimed to address challenges in effectively communicating new safety and efficacy data and changes in vaccination schedules to the public to increase acceptance and confidence in the science of COVID-19 vaccines.

- Additionally, the survey aimed to understand public perceptions that new COVID-19 variants may be less severe and that therapeutics may obviate the need for vaccination.

Discussion Summary

- This study provides international COVID-19 vaccine acceptance data over 3 years and found that …

- … acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccination in 23 countries was 79.1% in 2022, an increase from 75.2% in 2021.

- However, 12% of those already vaccinated were hesitant or reported refusal to receive a booster dose.

- The study also found that booster hesitancy is higher among younger ages, lower educational attainment and lower income groups, consistent with previous literature.

- Concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy, low trust in government and the perception that COVID-19 is a low risk were also reported as factors affecting vaccine hesitancy.

- The study also found that parental hesitancy to vaccinate children younger than 18 years is high in some countries, and that respondents reported the use of ivermectin as frequently as approved medication, despite the fact that it is not recommended for COVID-19.

- The study suggests that public health strategies to enhance vaccine coverage will need to differ in different settings, and efforts will be required to make the vaccine more accessible to children and discourage the use of non-approved pharmaceuticals.

What are the specific recommendations?

Strategies to improve vaccine literacy could include:

- messages that emphasize compassion over fear 53,

- message framing based on audience demographics and psychographics 54 as well as the use of trusted messengers 55, particularly healthcare providers 56, 57,

- and various types of incentives58.

- Frequency, content and channels of dissemination are key factors in message transmission and receipt.

- Public health communicators should regularly test messages and the source (messenger) for optimal reach and uptake 59 and integrate vaccine literacy strategies using qualitative formative research, such as focus groups among target audiences 60, to assess content on current (for example, first-dose and booster vaccination) and emerging (for example, mitigation of Long COVID) issues61.

Infographic

ORIGINAL PUBLICATION

A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in 2022

Nature Medicine

Jeffrey V. Lazarus 1,2 , Katarzyna Wyka2 , Trenton M. White1 , Camila A. Picchio1 , Lawrence O. Gostin3 , Heidi J. Larson 2,4,5, Kenneth Rabin2 , Scott C. Ratzan2 , Adeeba Kamarulzaman6 & Ayman El-Mohandes

January 9, 2023

Main

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic persists despite reductions in disease severity, hospitalizations and deaths since the introduction of multiple vaccines that protect against COVID-19 and pharmaceuticals to treat its symptoms1,2.

However, vaccine hesitancy and refusal continue to impede the effectiveness of these interventions3,4. Drivers of vaccine hesitancy are context-specific and include lower education, mistrust in science and governments5,6,7and misinformation8,9. Around two-thirds (66.4%) of the world’s population had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of 30 June 2022, but only 17.4% of people in low-income countries had received a first dose10, underscoring unequal access, availability and delivery11,12.

Global rates of COVID-19 vaccination are gradually improving, albeit unevenly.

Moreover, evidence suggests that the humoral response to vaccination is substantially reduced within 6 months13, necessitating additional doses (that is, boosters) to achieve adequate levels of protection14.

Vaccine hesitancy is a complex phenomenon15; prior studies of influenza vaccine hesitancy have identified more than 70 factors that influence it, many of which are time-specific and context-specific16.

Not surprisingly, the same factors that influence hesitancy to accept an initial COVID-19 dose also drive booster hesitancy: mistrust of government and health authorities, concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy and, in some countries, age and minority race or ethnicity5,6,17. The limited efficacy of current COVID-19 vaccines in preventing infection against new circulating variants could also influence acceptance18. Twice-yearly COVID-19 booster vaccinations are currently recommended in some countries based on eligibility and availability, and vaccines effective against new variants are in development19. Introducing updated vaccine formulations and frequent booster shots will intensify the challenge of convincing individuals and communities to accept new vaccines to maintain protective immunity, particularly as the risk perception of COVID-19 infection has decreased20.

Some obstacles to effective vaccine science communication for lay audiences may include …

- … the need to continuously disseminate new safety and efficacy data in simple, understandable terms;

- to explain the justification for newly authorized or reformulated products; and

- to introduce changes in vaccination schedules, especially for new or expanded authorizations of childhood vaccinations21.

Failure to convey this information clearly and consistently during the current pandemic may have confused audiences, eroded confidence in the science and reduced vaccine acceptance. The ongoing ‘infodemic’ of voluminous, high-speed information-accurate or not-further impedes vaccine literacy22.

Vaccination acceptance may also be dampened by public perceptions that new COVID-19 variants are possibly less severe 23 or that recently authorized therapeutics may improve disease outcomes well enough to obviate the need to vaccinate in the first place24.

Unfortunately, the emergence of highly infectious variants and the relaxation of public health and social containment measures in many countries will almost certainly trigger increased community transmission25.

The aim of this large survey in 23 populous and heavily impacted countries, representing almost 60% of the world’s population26, was …

… to track trends in global vaccine acceptance, to profile attitudes toward recently available COVID-19 boosters and pharmaceutical treatments and to assess attitudes toward several previously studied variables that appear to contribute to ongoing vaccine hesitancy at a critical time in the natural history of the pandemic.

Results

The global sample of 23,000 respondents included 1,000 participants from each of 23 countries surveyed …

… (Brazil, Canada, China, Ecuador, France, Germany, Ghana, India, Italy, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, Poland, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States) ( Methods).

Half of respondents (50.3%) were women, and one-fifth of respondents (22.2%) had a university degree. Age groups (18–29; 30–39; 40–49; 50–59; and 60+) were approximately equally represented (16.8–22.9%). Nearly half of all respondents reported income above their country’s median (45.6%). Healthcare workers (HCWs) represented one in ten (10.8%) of all respondents (Extended Data Table 1).

Vaccine acceptance in 2022 was reported by 79.1% of the respondents, up from 75.2% 1 year earlier 6.

However, vaccine hesitancy increased in eight countries (range 1.0% in UK to 21.1% in South Africa) (Fig. 1).

Booster hesitancy among those vaccinated was 12.1% (range 1.1% in China to 28.9% in Russia) (Fig. 2).

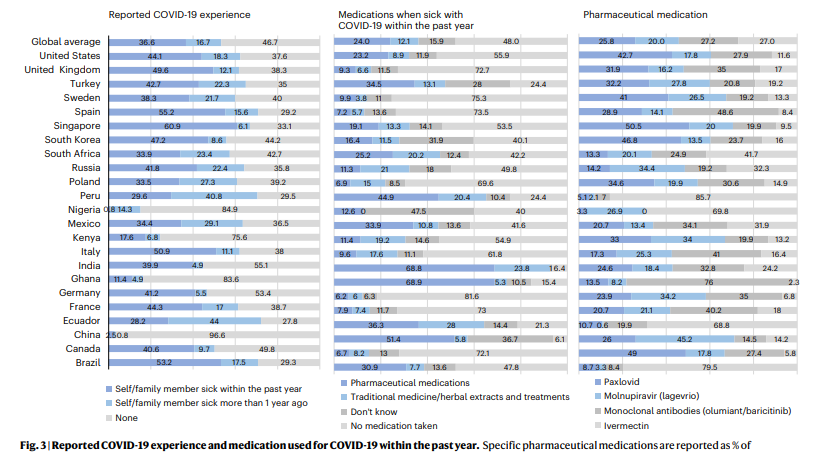

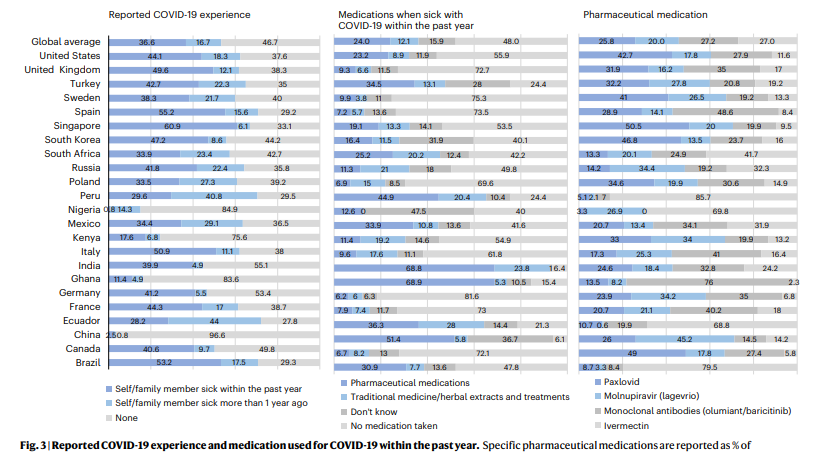

In total, 36.6% of all respondents reported COVID-19 illness (oneself or one’s family) within the past year (range 0.8% in Nigeria to 60.9% in Singapore), and 24% reported receiving treatment with pharmaceuticals (range 6.2% in Germany to 68.9% in Ghana).

Medications reported as having been used included

- monoclonal antibodies (olumiant/baricitinib) (27.2%),

- ivermectin (27%),

- Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) (25.8%) and

- molnupiravir (lagevrio) (20%) (Fig. 3).

Vaccine hesitancy was significantly more likely to be associated with males in Nigeria and Peru (adjusted odds ratio (aOR = 4.42–5.24)) and females in China, Poland and Russia (aOR = 0.06–0.67) and not having a university degree in France, Poland, South Africa, Sweden and the United States (aOR = 0.15–0.60) (Table 1).

Vaccine hesitancy was not universally associated with income distribution, as it was significantly higher among respondents earning less than their country’s median income in the United States (aOR = 2.35) and conversely higher among those earning more than the median income in Ecuador and Ghana (aOR = 0.07–0.13) (Table 1). Belief in a vaccine’s ability to prevent COVID-19 and in vaccine safety and trust in vaccine science remained strongly correlated with acceptance (Extended Data Table 7). Booster hesitancy among vaccinated respondents was significantly associated with younger age in France, Germany, Poland, South Korea, Spain and Sweden (aOR = 0.96–0.98) and with older age in Ecuador (aOR = 1.09); with male respondents in Ecuador (aOR = 5.69) and with female respondents in France and the United States (aOR = 0.53−0.57); with not having a university degree in Italy and South Africa (aOR = 0.28–0.52); and with earning less than the country’s median income in Canada, Germany, Turkey and the United Kingdom (aOR = 1.81–11.14) (Table 1).

Table 1 Association between COVID-19 vaccine and booster hesitancy and socio-demographic factors (age, gender, education and income) and current COVID-19 experience. a, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among entire sample and booster hesitancy among those vaccinated. b, Hesitancy for booster vaccines and for children among parents

See the original publiction (this is an excerpt version)

Parental willingness to vaccinate their children in the 23 countries studied increased slightly from 67.6% in 2021 (ref. 6), when COVID-19 vaccines for children were awaiting regulatory approval, to 69.5% in 2022. Over the past year, moreover, COVID-19 childhood vaccine hesitancy increased in eight countries (ranging from a 2.4% increase in Poland to 56.3% in Brazil) and remained greatest among parents who themselves were hesitant (Fig. 4). Childhood COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy was also significantly higher among older parents in Ecuador, India and South Africa (aOR = 1.03–1.19), among male respondents in Ecuador, Mexico and Peru (aOR = 3.41–5.33) and among respondents with less than the median national income in Canada, France, Germany and the United States (aOR = 1.86–2.96) (Table 1).

Support for COVID-19 vaccination mandates in 2021 ranged from 58.4% for vaccination of children to attend school to 74.4% for proof of vaccination for international travel6.

Support for all vaccination mandates in the 2022 survey decreased compared to findings in our survey from the previous year, ranging from −2.6% for employers to require vaccination to −6.9% for proof of vaccination for international travel, although support for the latter remained strong (69.2%). Support for mandates to vaccinate children to attend school, for adults to attend university and indoor activities and for governments or employers to require vaccination decreased in most countries (Fig. 5). However, support for government mandates did increase in 11 of the 23 countries (range 0.2% in Canada to 14.8% in Poland) (Fig. 5).

Vaccine hesitancy among HCWs decreased from 8.1% in 2021 to 4.6% in 2022 but was significantly lower than for non-HCWs (4.6% versus 9.4%, aOR = 0.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) (0.53, 0.78), P < 0.001)6.

Receipt of at least one booster dose was reported by 19.9% of HCWs compared to 40.3% of non-HCWs. Booster hesitancy among vaccinated HCWs was lower (9.7%) compared to 12.4% of non-HCWs (aOR = 0.79, 95% CI (0.71, 0.88), P < 0.001). Booster hesitancy was lowest among physicians (2.7%) and followed by nurses (9.9%), community health workers (10.4%) and other HCWs (16.3%) (Extended Data Table 2).

Almost two in five (38.6%) of all respondents said they now pay less attention to new information about COVID-19 vaccines than 1 year ago (range 7.5% in India to 58.3% in Nigeria).

Nonetheless, two-thirds of all respondents (66.6%) still prefer vaccination to prevent COVID-19 illness (range 40% in South Africa to 91.4% in China). In total, 16.2% of respondents preferred treating the disease with medication (range 2.8% in China to 31.2% in South Africa), and 53.2% believe that the vaccines can protect people from Long COVID (range 28.3% in Russia to 79.7% in India), but one-quarter (25.2%) of respondents indicated that they are now less likely to get vaccinated due to perceived lesser disease severity (range 4.2% in China to 43.1% in South Korea) (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Tables 3– 7).

Discussion

In the light of continued surges of COVID-19, policymakers around the world must decisively address vaccine hesitancy and resistance as a component of their overall prevention and mitigation strategy.

This study provides international COVID-19 vaccine acceptance data over 3 years and found that acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccination in 23 countries was 79.1% in 2022, an increase from 75.2% in 2021 (ref. 6).

However, in our survey, 12% of those already vaccinated were hesitant or reported refusal to receive a booster dose.

Among social and demographic determinants, our findings indicate that booster hesitancy is higher at younger ages27,28,29, unlike some previous studies that reported greater booster hesitancy among older persons30.

Our findings of greater hesitancy among those with lower educational attainment31and lower income17are consistent with the literature and unchanged from our previous reports5,6.

Similarly, our booster coverage ranges align with the existing literature-for example, from 7% in China32to more than 40% in Jordan33, Malaysia30and the United States31.

These rates were included in country-specific reports using different data sources, methodologies and chronology, whereas ours are reported on 23 countries simultaneously using a standardized method of data collection and analysis.

Our findings also corroborate previous literature showing greater hesitancy among those reporting concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy, low trust in government31,34and the perception that COVID-19 is a low risk35.

Despite overwhelming evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines36, these concerns persist for vaccine boosters29,37, which may present a serious challenge to anticipated routine COVID-19 immunization programs.

The lowest vaccination rates identified in our results are also bimodal; they exist outside of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and, therefore, cannot be explained by lack of access alone.

Public health strategies to enhance coverage will need to differ, sometimes radically, in different settings.

Parental hesitancy to vaccinate children younger than 18 years remained high in many high-income countries, including France, Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States and South Korea, as well as some LMICs, such as Kenya and Nigeria.

Key variables were low perception of vaccine safety38,39and younger parental age, which might represent potentially less-experienced parenting40,41, as well as parents who themselves had not been vaccinated38.

Interventions to improve parental intention to vaccinate their children include counseling or motivational interviewing by pediatricians or other healthcare providers, as well as narrative framing that presents the statistics on safety of these vaccines for the millions of children already vaccinated39.

Further efforts to make the vaccine more accessible to children in LMICs will also be required.

Our findings also report on receipt of therapeutics for COVID-19 globally and compare respondent preference for medicinal treatment versus prevention with vaccines.

Our respondents reported the use of ivermectin as frequently as the use of approved medications and products, despite the fact that ivermectin is not recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other leading agencies to prevent or treat COVID-19 (ref. 42).

Respondents who reported ivermectin use tended to reside in LMICs43.

Further efforts will be required to discourage the use of ivermectin and other pharmaceuticals with no proven efficacy and potential toxicity.

Respondents who reported ivermectin use tended to reside in LMICs43.

Further efforts will be required to discourage the use of ivermectin and other pharmaceuticals with no proven efficacy and potential toxicity.

To varying degrees, most respondents in our study support the use of mandates to contain COVID-19 in indoor spaces, the workplace, schools and universities and during international travel, although this support declined from the previous year6.

Although vaccine mandates have shown effectiveness in improving coverage in some regions-for example, the United States44and Europe45,46-their future use, particularly among populations with high rates of vaccination, will require a careful balance between the need for community protection and the need to maintain public support and voluntary compliance.

Communicating the rationale for instituting or reinstituting mandates for vaccination along with promoting vaccine literacy relative to preventive behaviors, such as face-masking and physical distancing, must improve, including the clarification of criteria for their relaxation or cessation.

It is well established and intuitively logical that frequent exposure to misinformation increases vaccine hesitancy8,47.

Misrepresentation of COVID-19 vaccines on social media most commonly includes misinformation about the medical/health benefits, false content about vaccine development and conspiracy theories48.

Those living in less developed countries may be more susceptible to misinformation49, yet, to date, research investigating online COVID-19 misinformation has been conducted primarily in high-income countries48,50, highlighting the need for similar research in LMICs, particularly those with high vaccine hesitancy and improved or improving access to vaccines40, to increase uptake.

Intentional or not, misrepresentation and misinformation can derail progress in COVID-19 vaccination coverage, …

… particularly if audiences choose not to seek COVID-19 information from official sources, such as WHO, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or medical professional associations.

These high-credibility sources of information face the additional challenges of pandemic fatigue41-or distress that may demotivate one to follow recommended protective behaviors-and, among some communities, low trust toward such institutions5,6,7,34,51.

The characteristics of people who currently pay less attention to COVID-19 vaccine information than 1 year ago vary by country, highlighting the importance of tailored health communication techniques (Extended Data Table 3).

As the pandemic continues, as new variants emerge and as public compliance with public health and social measures wanes, it is clear that those responsible for public health programs will need to develop more effective, personalized and sophisticated strategies to regain public attention and rebuild trust52.

Such programs must also be designed to include monitoring and, where appropriate, to address misinformation, as well as to develop and test other novel, effective communication methods.

Current efforts to fact-check online COVID-19 information have not kept pace with the ability of misinformation to reduce vaccine acceptance49.

Our findings may offer insight to policymakers and public health officials regarding message content and targeting.

Strategies to improve vaccine literacy could include

- messages that emphasize compassion over fear 53,

- message framing based on audience demographics and psychographics 54 as well as the use of trusted messengers 55, particularly healthcare providers 56, 57,

- and various types of incentives58.

- Frequency, content and channels of dissemination are key factors in message transmission and receipt.

- Public health communicators should regularly test messages and the source (messenger) for optimal reach and uptake 59 and integrate vaccine literacy strategies using qualitative formative research, such as focus groups among target audiences 60, to assess content on current (for example, first-dose and booster vaccination) and emerging (for example, mitigation of Long COVID) issues61.

Our study has several limitations.

First, our questionnaire asked about a general COVID-19 vaccine, whereas several COVID-19 vaccines, each with different efficacy results, are now being distributed globally.

Next, although this study used state-of-the-art sampling methodology that aimed to achieve population representativeness, these samples may not adequately represent the most vulnerable segments of populations, including those with limited access to online technology, as they would be less likely to participate in research of this type.

Additionally, we note that definitions for vaccine hesitancy do vary in the literature. We chose to categorize our data according to the 2014 Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) definition15rather than using the SAGE-endorsed Behavioral and Social Drivers (BeSD)62framing, which does not recognize the critical role of politics and/or political allegiance and orchestrated anti-vaccine networks/disrupters, all of which are critical issues influencing vaccine uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, although the BeSD framing acknowledges respect ‘from’ HCWs, it does not focus on the importance of mutual respect, despite the increases in aggression toward HCWs and scientists. The earlier WHO SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy defines vaccine hesitancy as ‘the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services’, which we thought could be captured in our dataset and compared to prior years (as described in the Methods) in a way that the full model of BeSD could not. Although the choice to use the 2014 SAGE definition is a limitation in that it does not fully reflect the most contemporary literature at the time of publication, we note that it still permits comparative analysis of factors included in both models, such as complacency, convenience and confidence factors.

Finally, this study was based on cross-sectional data; thus, study results cannot be interpreted causally.

The most promising finding of the 2022 global survey is that COVID-19 vaccine acceptance has continued to rise in most countries studied, reaching 79.1% overall.

However, the wide variability of acceptance rates that we report could jeopardize efforts to control the pandemic.

Our findings also show that, although most respondents accept booster shots and childhood vaccination, some unvaccinated individuals remain intractably opposed to immunizing themselves and their children.

Decisionmakers, practitioners, advocates and researchers must collaborate more effectively to address these lingering disparities and pockets of resistance with novel, tailored, evidence-based policies and programs.

To reverse trends of complacency and end the COVID-19 pandemic as a global public health threat, pandemic responses must include efforts to build trust and change the behaviors of unvaccinated, undervaccinated and indifferent people.

Decisionmakers, practitioners, advocates and researchers must collaborate more effectively to address these lingering disparities and pockets of resistance with novel, tailored, evidence-based policies and programs.

Methods & Other Sections

See the original publication (this is an excerpt version)

References

See the original publication (this is an excerpt version)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support for this study from the City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy Research Foundation (90057–00–99). J.V.L., T.M.W. and C.A.P. acknowledge institutional support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and State Research Agency through the ‘Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019–2023’ Program (CEX2018–000806-S) and support from the Generalitat de Catalunya through the CERCA Program. C.A.P. acknowledges support from the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca de la Generalitat de Catalunya and the European Social Fund as an AGAUR-funded PhD fellow. T.M.W. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and State Research Agency through the ‘Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019–2023’ Program as a PhD fellow.

Authors and Affiliations

Jeffrey V. Lazarus 1,2 , Katarzyna Wyka2 , Trenton M. White1 , Camila A. Picchio1 , Lawrence O. Gostin3 , Heidi J. Larson 2,4,5, Kenneth Rabin2 , Scott C. Ratzan2 , Adeeba Kamarulzaman6 & Ayman El-Mohandes

1 Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), Hospital Clínic, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

2 Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy, City University of New York (CUNY), New York, NY, USA.

3 O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA.

4 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), London, UK.

5 Institute for Health Metrics & Evaluation (IHME), University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

6 University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Nature Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jennifer Sargent, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Cite this article

Lazarus, J.V., Wyka, K., White, T.M. et al. A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in 2022. Nat Med (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02185-4

Originally published at https://www.nature.com on January 9, 2023.